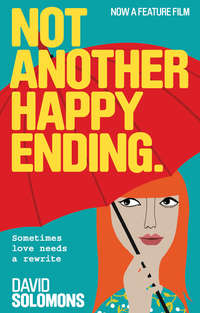

Not Another Happy Ending

THE BOWLER WAS a great idea. She rocked that hat. It was her lucky hat, always had been. Not that Jane could recall specific examples of its effect on her good fortune at this precise moment, but she was sure there must have been some in the past.

It was an awesome hat. It had been a last-second decision to take it to the meeting and she'd plucked it from its hook above the umbrella stand along with her favourite red umbrella. Not that the umbrella was lucky. Who has a lucky umbrella? In fact, weren't they notoriously unlucky objects? Yes, it was bad luck to walk under them. No, that couldn't be right. That was ladders, of course. Open them! You weren't supposed to open them indoors in case … what? Non-specific, umbrella-related doom, she supposed.

Oh god, she was losing it.

It was nerves. The email from Thomas Duval of Tristesse Books inviting her—correction, summoning her—to a Monday morning meeting had arrived last thing on Friday, leaving her all weekend to obsess. It had to be bad news; nothing good ever happened on a Monday morning. But if that were the case then why demand a meeting? If he wasn't interested in publishing her novel, surely he would have rejected her in the customary pro forma fashion, and he hadn't Dear Jane-d her, not yet.

She felt a spike of anticipation, which was instantly brought down by a hypodermic shot of self-doubt. Perhaps he was some sort of sadist who got his kicks torturing writers in person. But that seemed so unlikely. She'd been propping herself up with this line of thinking throughout most of the weekend, extracting every last drop of hope from it, until halfway through the longueur of her Sunday afternoon she decided to Google him and discovered that Thomas Duval was indeed just such a sadist. The Hannibal Lecter of publishing, blogged one aspirant author who'd evidently suffered at his hands. Attila the Hun with a red Biro, recorded another.

She dismissed the opinions of a few affronted authors—all right, fourteen—as a case of sour grapes and sought out a more cool-headed assessment of his reputation. There was scant information available on the Bookseller’s site, the industry's go-to journal, but she dug up half a dozen snippets of news. The names changed, but on each occasion the substance remained the same: breaking news—Thomas Duval falls out acrimoniously with another of his writers, who storms out in high dudgeon, swearing never to write one more word for that arrogant, temperamental sonofabitch.

Well, at least he was consistent.

She jumped on the subway at Kelvinbridge and rode the train to Buchanan Street in the centre of town. By the time she reached the surface, the early rain had given way to patchy sunshine and she enjoyed a pleasant stroll through George Square to the Merchant City. European-style café culture had come late to Glasgow—until 1988 if you said barista to a Glaswegian you risked a punch on the nose. But when it did arrive it came in a tsunami of foaming milk. An area of the city once referred to as the ‘toun’ these days sported sleek cafés on every corner, where, at the first warming ray, outside tables sprouted like sunflowers, and were just as swiftly populated by chattering, sunglasses-wearing crowds who always seemed to be waiting just off screen for their cue.

Jane headed along cobbled Candleriggs past the old Fruit Market, before stopping outside a set of electric gates. One of the residents was leaving and as the gates whirred open she slipped inside, finding herself in a large, sunlit courtyard bordered by a Victorian terrace on one side and a glassy office block on the other.

She made her way over to the far corner and at the door, she inspected the nameplate. This was the place all right. She hadn't really paid attention to the Tristesse Books logo before, but a large version of it was stencilled on the wall: a white letter ‘T’ suspended in a fat blue drop of rain. As she pushed the buzzer it struck her that it wasn't rain at all, but a teardrop.

Jane had been kicking her heels for half an hour, waiting in the hot, cramped Reception room for her meeting with Thomas Duval. She could hear him through the wall, shouting in rapid-fire French. He may not have been ordering a saucisson, but it wasn't difficult to catch the gist—someone was getting it in le neck.

Though his fury wasn't directed at her, with each fresh salvo Jane shrank deeper into the waiting-room chair. After fifteen minutes of listening to him rant she'd contemplated making her excuses and slinking out, but the possibility that he had read and liked The Endless Anguish of My Father was enough to encourage her to stay put and suffer.

Across the room she could see Duval's secretary trying to ignore the furious noises coming from his boss's office. At least, Jane assumed the man sitting at the desk was his secretary. For some reason she'd pictured Thomas Duval's secretary as one of those pencil-skirt wearing, bespectacled ah-Miss-Jones-you're-beautiful types, whereas the figure valiantly shielding the phone receiver from the angry French volcano on the other side of the wall was a twentysomething man in a brown corduroy suit and red bow tie. Now that she studied him carefully, he looked less like a secretary and more as if he was channelling a fifty-year-old schoolteacher.

‘Mm-hmm. Yeah. Oh yeah, he's a wonderful writer. So unremittingly bleak.’ The secretary paused as the caller on the other end of the phone asked a question. ‘No, Tristesse doesn't publish him any more,’ he said haltingly. ‘A little disagreement with …’ He glanced towards Duval's office door, cupping the receiver against the rising din. ‘She's one of my favourites!’ he said, responding to a fresh enquiry. ‘Yes, long-listed for the Booker, you know.’ His left eye twitched. ‘Right after she was sectioned.’ He listened again, one corner of his mouth sinking mournfully. ‘No. She left too.’

This was becoming ridiculous. How long would Duval make her wait in this tiny, airless cellar of a room? For all he knew she had taken time off her actual, proper job to show up at his beck and call. Not that she had a proper job any more. She'd quit the supermarket at the beginning of the year, when they offered her a place on the management trainee programme. She'd started off stacking shelves and here they were offering her a suit and a key to the executive WC. It was a sign; she knew, that if she took it then her life would go into the toilet metaphorically as well, taking her far away from her writing.

In the end it didn't even feel like her decision. She had to write; it was as simple as that. So she jumped, a great, giddy, don't-look-down leap of faith. And here she was. Forty-seven rejection letters later. Savings countable on the fingers of one hand … Was it stuffy in here, or was it her?

She yawned and stretched her legs, knocking the low table in front of her on which perched a stack of teetering manuscripts. They wobbled alarmingly and she dived to steady them, noticing as she did that the top novel was entitled A Comedy in Long Shot. Not a bad title. She immediately compared it with her own, placing each in an imaginary ranking system. Hers scored higher, she felt sure. The Endless Anguish of My Father had been tougher to come up with than the rest of the novel. But the day it popped into her head she knew it was the one. It had the ring of authenticity, rooted in truth, in life; six words that spoke to the eternal verities. And it looked good when she typed it across the cover page.

Something glinted behind the paper stack. A single golden page coiled into a scroll and set on a plinth. It was an award. An inscription ran along its base. She picked it up to read: ‘Thomas Duval. Young European Publisher of the Year, 2010.’ She turned the award another notch. ‘Runner-up.’

‘Miss Lockhart?’

Duval's secretary had crept up on her. Startled, she dropped the award. It landed against the wooden floor with a resounding clang and rolled under a sofa. Apologising profusely, Jane fell to her knees and scrabbled to retrieve it, a part of her brain belatedly registering that the shouting from the office had ceased.

‘What the hell are you doing?

She looked up into the face of Thomas Duval and felt her own flush. He was handsome in a way that would make Greek gods sit around and bitch. It wasn't the rangy stubble, or the thick wave of hair that demanded you run your fingers through its luxuriant tangle, or the intense stare from behind his Clark Kent spectacles. OK, it might have been some of those things. His distracting features were currently arranged to display a mixture of anger and puzzlement, but, she noted with a sinking feeling, they definitely tipped towards anger. She was also vaguely aware of a draught located around her backside and knew then that in her pursuit of the runaway award her skirt had ridden up and currently resided somewhere around her waist. As she covered her modesty (oh, way too late for that) she made a show of polishing the golden award with one corner of her sleeve.

‘I'm so sorry. I didn't mean to—I was just, y'know, touching it. I mean not touching—that sounds like molesting, like I'm some kind of pervert …’ she drew breath, ‘which I'm not.’ She ventured a smile. ‘Young European Publisher of the Year … Runner-up? That's really impressive.’ Don't make a joke. Don't make a joke. ‘I have a swimming certificate.’

Across the room the secretary chuckled, for which she was immensely grateful. Duval silenced him with a scowl. Certain that her submissive kneeling position wasn't helping her case, Jane picked herself up off the floor, laying a hand on the vertiginous stack of manuscripts for leverage. She leaned on the unsteady pile and the scripts toppled over, crashing to the floor. Random pages flew up around her ears.

Duval narrowed his eyes. ‘Who are you?’

She stuck out a hand in greeting. ‘Jane Lockhart …?’ Duval ignored the proffered hand. She withdrew it awkwardly, turning the action into a waving gesture she hoped came across as insouciant. ‘I wrote The Endless Anguish of My Father?’

‘Ah,’ he grunted. ‘Yes.’ He turned his back on her and began to walk away.

So that was it, she thought—another rejection. And I've shown him my pants.

‘What are you waiting for?’ he snapped over his shoulder.

She threw a questioning glance at the secretary, who motioned her to follow the disappearing Duval. Hurriedly gathering up her hat and umbrella she stumbled after him.

She was not sure what compelled her to do so—blame it on the confusion of believing she was about to be unceremoniously ejected onto the street—but by the time he had led her into his office she was again wearing the bowler hat. She was confronted with his broad back as he gestured her curtly into a low seat, then slid behind his desk and looked up. He leaned in with a quizzical expression, mouth half open.

‘It's my lucky hat,’ she pre-empted his question.

‘No one has a lucky hat.’

Something about this man made her want to argue. ‘What about leprechauns?’

He screwed up his face. ‘What?’

‘They're lucky. They wear hats.’ Oh god, she was doing it again. Stop talking. Stop talking right now. ‘Y'know, with the green and the buckle and … Ah … Ah!’ She sat up, raising one finger triumphantly. ‘You can have a thinking-cap.’

He sneered. ‘It's not the same thing at all.’

‘No. No it isn't.’ Sheepishly, she removed the offending bowler. ‘I only wore it to offset the umbrella,’ she confessed, then asked brightly, ‘Have you ever wondered why it's bad luck to open an umbrella indoors?’

Duval gazed at her steadily. ‘The superstition arose during the late 18th century when umbrellas were larger, with heavy, spring-loaded mechanisms and hard metal spokes. Open one in the confines of a drawing room and the consequences could be destructive.’

‘Oh.’

He drew a tired breath and fished a manuscript from under a pile. She recognised it immediately as her own, although the pages appeared crumpled at the corners and was that the brown crescent of a coffee stain on the cover? This must be a good sign. Clearly, the turned-down corners were evidence of the hours Duval had spent reading and then rereading; the stain conjured a long, espresso-fuelled night, his head bent over her novel mesmerised by the spare, elegant prose, those sharp, intelligent eyes tearing up at the emotive tale.

‘I'll be honest with you,’ he said, tossing the well-worn manuscript down on the desk, ‘I put this in the bin without reading a single word.’

Or, there was that.

She looked down and played nervously with her ring. It was made from an old typewriter key, the word ‘backspace’ in black letters on a silver background. She'd bought it with her last pay packet, a fitting gift to launch her on her new career as a novelist. She felt a lump in her throat and swallowed hard. She swore she wouldn't cry in front of him.

‘That title …’ He made a long, sucking sound through his teeth.

She had a feeling it wasn't the only thing that sucked. She glimpsed a straw and clutched at it. ‘But you took it out again.’

‘Hmm?’

‘Of the bin. Something must have made you take it back out.’

‘Yes.’ He fiddled with the small bust of Napoleon. ‘A fly.’

Had he just admitted to using the novel she'd slaved over for the last year and a half as a fly swatter?

‘It was a highly persistent fly,’ he added in a conciliatory tone. He pushed a bored hand through his hair. ‘I'm busy, so I'll keep this brief. I read your novel. I'm afraid it needs work. A lot of work.’

Hot tears pricked her eyes. She blinked furiously, trying to hold back the waterworks. She hadn't cried in years, not since her dad left, and now here was this man making her feel like that little girl again. It wasn't the rejection—she'd shrugged off dozens without resorting to tears. It must be him. The bastard. To actually reject her face to face.

‘But it has potential, so I'm going to publish it.’

What a complete and utter shit. Making her come all the way here just to wait in his stupid little office, only to be told—

Wait. What?

‘Ms. Lockhart?’ He peered into her stunned face. ‘Are you all right?’

‘Publish? Me?’ She just had to check. ‘In a book?’

He gave an exasperated sigh. ‘I'm offering you a two-book deal. It will mean a lot of rewriting—definitely a new title—and neither of us will get rich. But I think you have it in you to be a writer and, unfashionable as it may seem, that is what I came here to find.’

She waited for the punchline, searching his face for the appearance of a grin that would say, ‘only joking’, but it didn't come. He was serious. This man wanted to publish her novel. This kind, wonderful man. There was only one rational response to the news.

She dissolved into tears.

She'd always wondered how she'd feel if—she corrected herself—when the moment finally came and the flood of ‘no's’ was stemmed by one small, clear ‘yes’. In the end it wasn't even a ‘yes’ so much as a ‘oui’. Vive la France! Vive le Candleriggs! But this was more than an air-punching victory, it was … happiness. That's what it felt like. Through great hiccupping sobs she could see him watching her, confused. ‘I'm sorry. I didn't mean to …’she blubbed. ‘It's been so … so long … so many rejections … I have a board.’

‘You have a board?’

‘Of rejection letters. I call it my Board of Pain.’

‘Well,’ he said with a straight face, ‘that's completely normal.’

‘It is?’ Oh good, that was a relief.

‘So, how many publishers turned you down exactly?’

‘All of them,’ she said, palming away tears. ‘Well, obviously not all of them. All of the big ones, I mean.’ She caught his eye. ‘Not that I'm saying you're not big. I'm sure you're very … important. I mean, really, I should have sent you my novel ages ago, given that it's set in Glasgow and so are you.’

‘So why didn't you?’

‘Umm.’ This was awkward. ‘Because I'd never heard of you?’

He grunted.

‘But then I read The Final Stop by Nicola Ball and I loved it and she is really talented and really young and I saw your logo on the spine and, well, here I am.’

She lapsed into a renewed bout of weeping.

The office door swung open and the secretary in the brown suit entered, flourishing a paper tissue from a man-sized box. He'd come prepared. ‘I'm sorry about him. He was like this at uni. Everywhere he went—crying women.’

She took the tissue and blew her nose loudly.

‘Roddy—’said Duval, trying to explain that, as unlikely as it appeared, this time he was not the cause of the great lamentation.

Roddy wagged a finger. ‘Uh-uh. You lot are supposed to be charming. Charmant, n'est-ce pas?’

Jane shook her head, struggling to form words through the wracking sobs.

‘I've told you,’ snapped Duval, ‘never try to talk French to me, you—’

‘Happy!’ Jane's outburst silenced both men. ‘No, really.’ She bounced out of the low seat. ‘I've … I've never been so happy in all my life.’

She hugged a surprised Roddy and then circled round his desk to embrace Duval. Gosh, up close he was very tall. In her exuberance she knocked over her umbrella. It sprang open, an inauspicious red blot in the centre of the room.

But it was probably nothing to worry about.

CHAPTER 3

‘Nine Million Rainy Days’, The Jesus and Mary Chain, 1987, Bianco y Negro

‘THIS IS THE marketing department … And this is sales … And this is publicity.’

‘Hi, I'm Sophie,’ said a shiny young woman with a sleek bob and perfectly applied make-up.

‘Sophie Hamilton Findlay,’ said Tom, ‘three names, three departments. You blame Sophie if no one reviews your book, or if you can't find it in all good bookshops. Don't blame her for not marketing it … I don't give her any money for that.’

They turned a hundred and eighty on the spot.

‘And this is George. He's production.’

A pinched face looked up from a wizened baked potato overflowing with egg mayonnaise.

‘I'm on lunch.’

‘You blame George if the print falls off the page, or if the pages themselves fall out. So, you've met the rest of the team. Any questions?’

‘Well …’ Jane began.

‘Good.’ Duval clapped his hands. ‘Time to get to work.’

When he suggested heading out of the office for their first editorial meeting Jane pictured them moving to a quiet corner of Café Gandolfi sipping espressos and arguing about leitmotifs. He had different ideas. One thinks at walking pace, he pronounced, and took off along Candleriggs at a clip, brandishing her manuscript and a red pen. Andante!

She scurried after him, his loping stride forcing her to trot to keep up. The man thought fast. He did not approve of the modern fashion of editing at a distance, he explained, with notes issued coldly via email; adding with a grin that he preferred to see the whites of his writers’ eyes.

‘Readers are only impressed by two things,’ he said. ‘Either that a novel took just three weeks to write, or that the author laboured three decades.’ He sucked his teeth in disgust. ‘And then dropped dead, preferably before it was published. No one cares about the ordinary writer. The grafter. Like you.’

Ouch. A grafter? Really? She'd been harbouring hopes that she was an undiscovered genius.

‘And publishers are no better.’ He turned onto Trongate, carving a swathe through commuters and desultory schoolchildren, warming to his theme. ‘Do you recall that book about penguins?’

‘Which one?’ The previous year the book charts seemed to be awash with talking penguins, magically realistic penguins, melancholy penguins, there had even been an erotic penguin.

He slapped a hand against her manuscript. ‘My point exactly! One book about penguins sells half a million copies and suddenly you can't move for the waddling little bastards.’ He stopped, slumping against a doorway. His shoulders heaved like a longbow drawing and loosing. ‘The giants are gone,’ he said sadly.

Giants? Penguins? Was every day going to be like this? He set off again at a lick.

‘So many modern editors neglect the great legacy they have inherited. They are uninterested in language or, god forbid, art; and would prefer a mediocre novel they can compare to a hundred others than a great one that fits no easy category. They care only about publicity and book clubs and film tie-ins.’ He spat out the list as if it curdled his stomach. ‘Most editors are little more than cheerleaders, standing on the sidelines waving their pom-poms.’ He turned to her. ‘I have no pom-poms,’ he growled. Then thumped a palm against his chest. ‘I care. I care about the work. I care about your novel.’

He stopped again and she felt she ought to fill the silence that followed. ‘Thanks,’ she said brightly.

Duval cocked his head and looked thoughtful. ‘Of course, it is not a good novel.’

Sonofa—

‘But it could be.’ He pushed a hand through his hair. ‘So I say this to you now, without apology. From this moment, Jane, we will spend every waking hour together until I am satisfied. It will be hard. Lengthy. I will make you sweat.’

Uh, could he hear himself?

‘I will stretch you. Sometimes I will make you beg me to stop.’

Apparently not.

‘I do this not because I am a sadist—whatever you might have heard—I do this to give an ordinary writer a chance to be great.’

That was terrific, she was impressed—moved, even—but could he not give the ‘ordinary writer’ stuff a rest?

They came to a busy intersection. Pedestrians streamed past them. At the kerb the drivers of a bus and a black cab loudly swapped insults over a rear-ender; the aroma of frying bacon fat drifted from a van selling fast food. He ignored them all, shutting out the traffic and the smells and the noise, for her.

‘I promise that no one has ever looked at you the way I shall. Not even your lover.’

Jane swallowed. ‘I don't have a lover,’ she heard herself admit. ‘Right now I mean. I've had lovers, obviously. Not loads. I'm not, y'know, “sex” mad. I don't know why I brought up sex. Or why I put air quotes round it. I'm totally relaxed about … y'know … sex. And yet I just whispered it. Very relaxed. I think it's because you're French. You're all so lalala let's have a bonk and a Gauloise. Oh god. I'm so sorry about … well, me, Mr Duval. Should I call you Mr Duval? It sounds so formal. Maybe I could call you Robert.’

‘You could,’ he said, ‘but my name is Thomas.’

‘Thomas! Yes. I knew that. I was thinking of the other one. From The Godfather? Played the accountant.’

‘Tom.’

‘No, it was definitely Rob—oh, I see. Tom. Short for Thomas. I had a friend called Thomas. Well, when I say “friend” I—’

‘Stop talking.’

‘Yes. Yes, I think that would be a good idea.’ She dropped her head, stuck out a foot and screwed a toe into the pavement.

‘OK,’ he declared. ‘Now our work begins.’

And with those words the months spent at her desk writing for no one but herself were at an end. Now they would embark on a journey of discovery, together, to prepare her novel for … Publication. Suddenly, the sacrifices seemed worth it: losing touch with friends, turning on the central heating only when the ice was inside the windows, baked beans almost every day for three months straight, all to reach this pinnacle of a moment.

‘Do you want a roll and sausage?’ asked Duval.

‘Do I want a—?’

He marched off in the direction of the fast-food van.

‘Morning, Tommy,’ the owner greeted him. ‘The usual?’

‘Aye, Calum, give me some of that good stuff.’ Duval took the sandwich, then showed it excitedly to Jane as if he were a botanist and it a new species of orchid. ‘And not just any sausage, oh no. A square sausage. See how it fits so perfectly inside the thickly buttered soft white bap? Genius! But then, what else would one expect from the nation who gave the world the steam engine, the telephone and the television? This is why I love the Scots. Now, a soupçon of brown sauce.’ He squeezed a drop from the encrusted spout of a plastic bottle, patted down the top of the roll and sank his teeth into it. Paroxysms of delight ensued. ‘And to think that France calls itself the centre of world cuisine.’