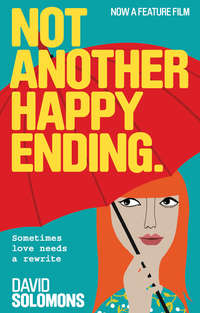

Not Another Happy Ending

She wasn't entirely sure he was joking. And then she realised. He'd gone native.

‘You must try one. I insist.’ He clicked his fingers as if he were ordering another bottle of the ’61 Lafite.

Moments later she stood peering at the sweating sandwich in her hands, and beyond it, Tom's grinning face.

‘OK,’ he said. ‘Now we begin.’

Ten minutes later they sat beside one another in the window of a café next door to his office. Between them lay the ziggurat of her manuscript.

‘Jane,’ he said softly, ‘there is no need to be nervous.’

‘Nervous? Me? No-o-o. Not nervous.’ A coffee machine gurgled and hissed, only partially masking the spin cycle taking place in her stomach. ‘OK, a little bit nervous.’

He smiled. ‘It's OK.’

It was then she realised what was making her nervous. He was being nice to her. The heat had gone out of his fire and brimstone, his voice, typically tense with anger, now soothed like warm ocean waves.

‘Usually I need a run-up before I start editing,’ she said. ‘Y'know: tea, a walk, regrouting the shower.’

‘Or we could just begin?’

‘What, no foreplay?’ Even as she spoke them she was chasing after the words to stop them coming out of her mouth. But it was too late. He gave a small laugh, the sort of laugh your older brother's handsome friend might give his mate's little sister. Jane's embarrassment turned to disappointment. ‘So, where d'you want to start?’

‘Call me crazy, but we could start at the beginning.’

‘OK.’ She nodded rapidly, appearing to give his suggestion serious consideration, hiding her mortification at asking such a dumb question. ‘OK yes.’ She clouted him matily on the arm. ‘You crazy Frenchman.’

He turned the top page of the manuscript. And they began.

He gave great notes. They were acute, considered, wise. Intimate.

As he had promised, the process of editing her novel forced them into a curious form of co-habitation. She would arrive at his office each morning and, following his customary breakfast of roll and sausage and black coffee, they would commence work. At first on opposite sides of his desk, then on the third day he came out and sat on the edge, balancing there comfortably, at ease in his body; a move, Jane did not fail to notice, which put her at eye level with his crotch.

Often she felt like the submissive in a highly specific S&M relationship, one with no physical contact but plenty of verbal discipline. I edit you. I. Edit. You. Ordinarily, she wouldn't have put up with any man who bossed her about as much as Tom did, but theirs was a professional relationship, she reminded herself. So she gave herself permission to be spanked. On the page.

Mostly they worked in his office, or the café next door, and whenever they reached a sticky point they would take to the streets and walk it out like a pulled muscle. Occasionally they decamped to her place. The first time he asked her—no, informed her—of the change of venue came early one morning while she was still half asleep, drowsy with last night's notes. He was on his way over, said the familiar accented voice on the other end of the phone.

When the doorbell rang she was in the shower. She stepped out, dripping, to shout down the corridor that there was a key on the lintel above the door and he should let himself in. It felt natural to give this man the run of her flat. After all, he was going to publish her. When she entered the sitting room she found him sprawled on the floor, propped on one elbow, pages scattered about him, red pen zipping through the manuscript. He looked right at home. And, watching him work steadily, intensely, she realised that he was the first man she'd properly trusted since her dad walked out.

They settled into their routine. Every day it was just the two of them, happily suspended in a bubble of literary discourse and fried egg sandwiches. One Wednesday morning, ten chapters into the edit, Jane breezed through the front door of Tristesse Books.

‘Morning, Roddy.’ She plunked a bulging paper bag on his desk. ‘I made brownies.’

There was an urgent rustle as Roddy tore open the bag. With an appreciative smile, she turned towards Tom's office. She liked Roddy; he was a good influence on Tom. If Tom had a fault—and he did—it was an impulsiveness that shaded into arrogance, and Roddy was the one who called him on it, every time. Although it was dubious how he balanced his job as a replacement English teacher with secretarial duties for Tristesse Books, he exuded an air of moral rectitude along with an insatiable appetite for her home baking. He was Jiminy Cricket to Tom's Pinocchio, she'd informed both men one cool summer night, as they sat outside at Bar 91 amidst the buzz of revellers welcoming the weekend. Tom had almost choked on his pint. Roddy just looked disappointed: couldn't he at least be Yoda to a hot-headed young Skywalker, he'd asked.

‘Uh, Jane. You can't go in there.’

She stopped at the door, one hand poised over the handle.

‘He's got someone with him. They've been in there all night.’

She could hear Tom on the other side, his voice in its by now familiar trajectory, the point and counterpoint of argument, the steady inflection and unwavering logic of his contention. And it hit her. He was giving notes.

To someone else.

She experienced a sudden light-headedness, like an aeroplane cabin depressurising at altitude, and was still reeling when the door opened and a winsomely pretty blonde girl stepped out of the office and collided with her.

‘Ooh, sorry.’

‘Sorry.’

‘No, I should be the one who … sorry.’

They disentangled themselves and the girl introduced herself.

‘Nicola Ball.’

She was wearing a severe black pinafore dress on top of a white shirt buttoned to the neck. Pellucid blue eyes gazed unblinkingly from a perfectly oval face. There was a hint of redness around her eyelids, as if she'd been crying.

‘The Last Stop,’ said Jane delightedly. ‘I loved that book.’

‘Thank you,’ said Nicola, a tremulous smile appearing on pale lips. Then her expression hardened and she cast a dark look back through the doorway to Tom's office. ‘At least someone appreciates me,’ she snarled.

‘Why are you still here?’ Tom's voice boomed out. ‘Stop socialising and start rewriting. Go. Now!’

‘I hate that man,’ Nicola hissed.

As she said it Jane felt an unexpected sense of relief. Nicola hated Tom. Good.

‘Please tell me you're not one of his,’ said Nicola.

‘Uh, one of—? Oh, I see. Well yes, I am—as you say—one of his,’ said Jane, adding an apologetic shrug since Nicola's sombre expression seemed to demand one. ‘Tom's going to publish me.’

Nicola took her hand and patted it consolingly. ‘I'm so sorry.’ She pursed her lips in an expression of graveside condolence, bowed her head and departed.

Jane watched her slip out, the triangle of her pinafore dress swinging like a tolling church bell, and felt herself smile inwardly; whatever Nicola's experience of working with Tom had been, it bore little resemblance to her own.

‘Jane?’ he called from the office. ‘Is that you?’

She never tired of hearing him say her name. She floated inside on a cloud of happiness ready to embark on the next leg of their voyage of collaboration and constructive criticism, of intellectual discussion and high-minded debate.

‘Your notes,’ Jane spluttered. ‘Your notes are burning cigarettes stubbed out on the bare arm of my creativity.’ She stepped away from his desk only to return immediately. ‘Oh, and there is no such thing as constructive criticism. The phrase reeks of foul-tasting medicine forced down gagging throats “for your own good”. Constructive criticism is a fallacy; weasel words designed to lure innocent writers like me into an ambush. This chapter is too long. There's too much set-up. This plotline doesn't pay off. Uh, perhaps that's because you cut the set-up? This character is underwritten. Show, don't tell! This chapter is still too long. I like this scene, this is a great scene—it must be cut.’ She stood before him, her face flushed, her breath shallow and rapid.

‘Are you quite finished?’ Tom responded with irritating calm.

She brushed her fringe from her eyes and sniffed. ‘Yes.’

‘Good, then we shall continue.’

Two months into the edit and Jane had lost all sense of perspective. Was he a brilliant editor or, despite his earlier disavowal, simply a sadist who enjoyed torturing novelists? Currently, she was leaning towards the latter. She half suspected that were she to pull at the antiquarian volume of Frankenstein squatting atop his bookcase a secret door would swing open to reveal a shadowy chamber and the gaunt, moaning figures of his other novelists, hanging from bloodstained bulldog clips, notes on their last drafts carved into their skin with his annoying and ubiquitous little red pen. It pained her to admit it, but Nicola Ball's expression of pity had been prophetic.

She occupied her usual spot, squirming in the low chair opposite his desk. They sat in silence as he went through her latest revisions, the only sounds the dismissive flick of manuscript pages and the scratch of that damn pen. She watched as he adjusted the bust of Napoleon, turning it precisely one inch clockwise, then two inches anti-clockwise. He did this with some regularity, but it was only latterly she'd realised that the tic inevitably preceded his delighted unearthing of a particularly egregious flaw in her manuscript.

‘This makes no sense at all,’ he muttered on cue, striking out a paragraph with a flurry of red slashes.

‘What are you cutting now?’ Sometime on Thursday she had given up any attempt to hide her irritation.

He looked up and she was sure that his smug, infuriating face evinced surprise at her presence. Why are you even here? it said. What could you possibly have to contribute to this process? You are merely the writer. Jane struggled out of her chair—she'd meant to leap up for added effect, but her prone position made it tricky.

‘I've changed my mind,’ she said, reaching across the desk for her manuscript. ‘I don't want to be published. By you. Thank you very much.’

She had no practical reason for retrieving the manuscript; if she'd really meant what she said she could simply have walked out of the door, gone home and printed out another—but she wanted to take something away from him. She had gathered an armful of pages when she felt his hand close gently but firmly around her wrist. She was startled; was it the first time he'd touched her?

Last week she'd been surprised that he hadn't kissed her in the French style—not that French style—when she'd finally signed her contract and left with a cheque that would pay for a fabulous trip to Moscow (the one in Ayrshire, natch). It had seemed to her that he started to lean in over the signature page for the customary embrace, but pulled back at the last moment. He'd been close enough for her to feel the leading edge of his well-groomed stubble and smell his skin. She'd half expected his natural scent to be Lorne sausage, but instead he was a heady mixture of sandalwood and new books. Then why his hesitation? She had swilled copious amounts of mouthwash that morning in preparation for the signing. Just on the off chance, you understand. So it wasn't her breath. Perhaps he simply didn't fancy the idea of kissing her. Well, his loss.

He was still holding her wrist. And, for a moment, she wondered what it would be like to do it right here on his desk.

‘You can't do that,’ he said firmly.

‘I know,’ she said, shocked at where her mind had taken her. ‘Knowing my luck I'd probably end up with Napoleon in my back.’

Jane saw that he was looking at her in utter bafflement. She had seen a similar expression on his face earlier that day over a complicated sandwich and a cappuccino at the café next door. Pushing his coffee to one side he had complained that until meeting her he'd imagined his English not only to be fluent, but idiomatic—and prided himself on being almost certainly the only living Frenchman who knew his bru from his broo. However, in conversation with her he often felt like a foreigner, he said. No. Correction. Like an alien. She hadn't said so, but secretly she enjoyed the thought that she unsettled him.

She shrugged off his hand, glowered at him to get it out of her system and then with a sigh lowered herself into the knee-height chair once more. She waved at him to continue. ‘You were cutting what was no doubt my favourite passage.’

‘Bon,’ he said, gratified, and scored viciously through another paragraph.

As she watched his scurrilous red pen she wondered when it had all gone wrong. A few weeks ago she had even made him her flourless chocolate cake. Though now she thought about it the baking interlude had arisen because one of his notes had sent her into a tailspin and she had been unable to write a single word for days. Yes, she realised, he was turning her into a crazy person.

As he droned on detailing the endless failings in her novel, she decided something had to be done. What was it about Tom that made her heed his every pronouncement? It wasn't just the sculpted stubbly chin, it was the self-confidence acquired from years at an exclusive French boys’ school followed by university degrees acquired in two languages. The closest she'd come to university was on the tills at the supermarket selling lager to boozed-up students on a Saturday night.

She found herself scanning the contents of the bookcase that filled the wall behind his desk, running her eye across the well-thumbed classics, vintage and modern, dozens of them seeded with slips of paper marking favourite passages. It was a display designed to impress. But then with a little rush she realised that she'd read most of them in the library in Dennistoun during those long afternoons. She sat a little straighter—she probably knew them as well as he did. Her gaze settled on a volume of Greek myths and an idea struck her.

The problem was territorial. Like the myth of the giant Antaeus, who drew his strength from his connection to the earth, all she had to do was separate him from the square mile of the Merchant City and she was sure their relationship would achieve new levels of equality and harmony. She needed to pluck him from his comfort zone and repot him. She smiled to herself—she knew just the place.

CHAPTER 4

‘Laughter in the Rain’, Neil Sedaka, 1974, Polydor Records

‘YOU SAID IT WAS a Highland cottage.’

‘Yes.’

‘I heard you distinctly. An old crofthouse nestling at the end of a glen, you said.’

‘Yes.’

‘But …’

‘Yes?’

‘You made it sound …’ he hunted for the right word ‘… picturesque.’

Ignoring his accusing tone, she motioned towards the small stone dwelling with a gesture of ‘ta-da!’

His eye roved suspiciously across the outside. A chimney stack balanced like a drunken man on the roof; weeds sprouted from slate tiles that had been discarded rather than laid; of the two windows cut roughly into the facing wall, one was bricked up and the other colonised by a family of squabbling, drab-feathered birds. The whole structure tilted at a twenty-degree angle, leaning into a relentless, biting wind that howled down the most desolate glen he had ever seen.

‘Does it leak?’

Her mouth gaped, offended. ‘Of course it doesn't leak.’ She turned away, fished out a great iron key from her weekend bag, slid it into the stiff lock and shouldered her way inside. ‘So long as it doesn't rain,’ she mumbled.

There was a sucking squelch from behind her.

‘Of course. What else should I expect? Just wonderful.’

He stood up to his ankles in a sloppy brown puddle. Jane wasn't sure which looked more soggy—his trousers or his face. When she had suggested the trip up north to work on the manuscript—to finish it once and for all—she told him to bring suitable outdoor wear. So, when he'd picked her up in his car that morning, she couldn't help but notice with some surprise that he was wearing orange trainers. She declined to comment at the time; he'd obviously picked them as a reminder that he didn't have to listen to her—he was the one who gave the notes in this relationship. Well, look where it got you, she thought smugly. I say potato, you say pomme de terre.

The muddied orange trainers steamed gently in front of the fireplace as Jane stoked the sputtering fire. Beside her, Tom shivered in a faded tweed armchair, hugging himself and grumbling.

‘What's wrong now? You haven't stopped moaning since we left Glasgow.’ She threw on a handful of kindling. ‘Don't you like it here? This was my granny's cottage.’

He snorted. ‘You're telling me your granny was a crofter?’

She noted that he didn't say ‘farmer’, but used the Scottish expression. He was amazing. His English. Was amazing. Not him. He was annoying. ‘She worked on the line at Templeton's Carpets,’ she explained.

‘So, she bought this place?’ He sounded incredulous at the idea anyone would put down hard-earned money for such a dump.

‘She won it. Back in the ‘80s. One of those dodgy timeshare offers came through the door.’ He gave her a blank expression. ‘Y'know the sort of thing: You have already won one of these great prizes: a wicker basket of dried flowers, a canoe, or a Highland hideaway. All you had to do to claim your prize—and it was always the dried flowers—was sit in a conference room in an Aviemore hotel and listen to some guy's sales pitch. But my granny hit the jackpot.’ She motioned, quiz-hostess style. ‘The Highland hideaway.’

‘And to think she could have walked away with a canoe.’ He cast a disgruntled eye around the dim room. ‘If you'd wanted a change of scene there are perfectly good cafés on Byres Road,’ he grumbled. ‘With Wi-Fi.’ He flicked the switch on a standard lamp sporting a fetching floral shade. The room remained dim. ‘And electricity!’ he barked. ‘This is not natural.’

‘What are you talking about? Outside that door is actual nature.’

‘Nature is for German hikers in yellow cagoules.’ He scraped the chair across the floor, closer to the fire. ‘Can't you turn this thing up?’

Jane tossed on another log and retreated to the kitchen to make coffee. It was a while since she'd been up to the cottage. When she'd begun the novel she imagined retreating to its splendid isolation. In her head it would go like this: during the day she would alternate writing by the window (that would be the one window with glass in the frame) with long walks in the countryside where she would be inspired by clouds and daffodils. At night she would curl up by the fire and continue scratching out her masterpiece. She had decamped to the cottage to live the dream, only to find the power out, as usual. Four hours later her laptop battery died and she lost half of the chapter she'd been working on. That was the end of the romance. She returned to Glasgow the following morning and hadn't been back since.

The cupboard contained a single jar of Nescafé, a tin of powdered milk and a suspicious trail of what she hoped were only mouse droppings. She warmed the drink on an old Primus stove. It pained her to admit it, but Tom was right; the place was little more than a ruin. But it was her ruin. Her gran had left it to her, not her mum. Gran hadn't approved of mum's choice of husband—she was an astute judge of character—and though there was no grand title or country estate to disinherit her from, there was the cottage.

Tom called from the other room, imploring her through chattering teeth to hurry up with the coffee. She put up with his hectoring, thankful he wasn't asking where to find the toilet. She was delaying the inevitable moment when she had to explain the purpose of the spade by the front door.

He had moved from the armchair onto the hearth, and as she approached she saw he was holding her manuscript. She sighed. It was straight to business then.

‘Sit down.’

‘You're incredibly bossy, anyone ever told you that?’ she complained, sitting nonetheless.

‘Yes. Now be quiet and listen. This is the chapter where Janet goes to her favourite sweetshop—’

‘Glickman's,’ she interrupted. It was on the London Road. A Glasgow institution, the oldest amongst dozens in that sweet tooth of a city. Her dad used to take her on a Saturday morning to spend her pocket money: a bag of Snowies for her—moreish drops of sweet white chocolate covered in rainbow-coloured sprinkles; and a quarter of tangy Soor Plooms for him that made her mouth tingle. He always let her pay for his—a warning sign of things to come.

Jane folded her arms, bracing herself for his critique. ‘OK, so what's wrong with it? Wait, don't tell me. It's the Soor Plooms—too specific—they won't understand the reference in Croydon.’

He said nothing and instead reached into his bag for a small, white paper bag. It rustled with unbearable familiarity.

‘Are those from Glickman's?’ she asked, already knowing the answer.

He chuted the contents into his hand. Out tumbled white chocolate Snowies.

She felt sick.

He held out a single sweet with the quiet unblinking confidence of a man who knows that when he wants to kiss a girl it is inevitable; at some point she will kiss him back. He offered the sweet to her, both of them understanding that she would succumb.

‘Your dad—’ He shrugged. ‘Forgive me, Janet's dad—was an alky and a total bamstick, but you took that pain and turned it into a novel which, for the most part, isn't awful.’

‘I'm not Janet.’

He made a face as if to say, oh really? ‘A less scrupulous publisher would insist on calling this a memoir,’ he said with a nod towards the manuscript. ‘He would conveniently skip over the few sections that are fiction and sell a hundred thousand more copies. Readers love pain, particularly if they know someone really suffered.’

‘I'm not Janet.’

‘Now, for the sake of editorial distance, you need to let her go.’

‘Editorial distance?’ She felt the sag of disappointment. So this was just about the edit.

‘Yes. What else?’ Tom leant forward. ‘Janet is about to have a new life on the page. Soon, your character will belong to thousands of readers—’ he grimaced ‘—well, hundreds. You two need to go your separate ways.’ He paused. ‘So we are going to make a new memory. One that belongs to you, not her. Here, in this picturesque shit-hole.’

He pushed the Snowie towards her. ‘You are not Janet.’

‘I can't. I haven't had once since Dad …’

‘I know.’

Slowly, she parted her lips. He popped the sweetie on her tongue and her mouth filled with warm chocolate and the crunch of hundreds and thousands.

In the morning she found him asleep in the armchair, arms wrapped around her manuscript. Was it possible to feel jealous of your own novel? Nothing had happened after Snowie-gate; he had behaved like a gentleman, keeping the conversation professional, the mood workmanlike. Which was absolutely fine with her. A-OK. Hunky-flipping-dory. After all, it was perfectly natural for a modern young woman to invite an attractive man she barely knew to a cottage in the middle of nowhere. A cottage with one bedroom. There was no pretext; this weekend was all about the sex. Text. The fire had burned itself out overnight. No, that wasn't a metaphor. She gathered a handful of kindling from the basket next to the grate and built a new one.

At his suggestion after breakfast they spent the day walking the length of the glen. Around lunchtime it opened out to a dark, glassy loch. The sun was breaking through the thick layer of cloud when they came to a large flat rock by the edge of the water and Tom insisted on stopping. He reached into a chic leather messenger bag, and Jane was sure it was to retrieve the manuscript, but to her surprise he produced a couple of gourmet sandwiches from Berits & Brown and a portable espresso maker, from which he proceeded to make the most delicious cup of coffee she'd ever tasted.