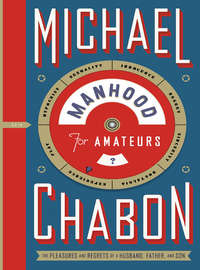

Manhood for Amateurs

“Why are we doing this again?” my wife asked me, not for the first time, on the night of the seventh day of our second son’s life.

We were in bed, sitting up against the headboard, semi-comatose, dazzled by sleeplessness in a way that felt shared and almost pleasurable. The baby was at her breast, working his jaw, the nipple impossibly huge in his astonished little mouth. I leaned my shoulder against my wife’s, and she laid her head against my cheek, and together our bodies formed a kind of cupped palm around the baby in her arms. The lamp clipped to the headboard enclosed us in a circle of soft light. I doubt that any rational observer could have inferred from that intimate huddle, from the shelter we had formed of ourselves, the date we had made for the baby and his foreskin at one o’clock the following afternoon.

“I guess,” she said, attempting to answer her own question, “he ought to match his big brother.”

“I guess,” I said, recognizing this as a variant of a common justification advanced by Jews inclined, in most other respects, to disregard the Commandments of the God of Abraham: that it would somehow disturb or gravely puzzle a child to contemplate the difference in appearance between his own hooded penis and his father’s peeled one. Possibly it might hang him up about penises in general. In turn this might lead, via unspecified, possibly mythical, psychological processes, to some kind of sexual dysfunction, oedipal collapse, Kafkaesque problems with authority.… That part of the argument tended to get left to the imagination. It was usually enough to intone the reasonable principle that a son ought genitally to match his father in order to evoke a cognizant nod of the head in the listener – a spouse, a gentile friend, a gentile spouse. I knew this matching-penises argument was a favorite among interfaith couples, frequently advanced by the non-Jewish partner as she attempted to get her mind around the idea of letting some nut with a scalpel come after her baby’s little thing.

“But who knows?” I continued. “None of their other parts have to match. They could have different eye color, different hair, different noses, differently shaped heads. One of them could have a fissured tongue or a rudimentary third nipple.” I have a rudimentary third nipple, which was why this particular example occurred to me. “What’s the big deal about the penis? By the time this guy here gets old enough that he starts making a critical study of penises, he probably won’t be seeing his brother’s very often.”

“Yeah,” she said, letting the argument flutter to the ground like a losing lottery ticket.

We had been through all of the standard arguments – hygiene, cancer prevention, psychological fitness, the Zero Mostel tradition – the first time around, with our oldest son, and found that they are all debatable at best, while there is plenty of convincing evidence that sexual pleasure is considerably diminished by the absence of a foreskin. But I never know how to think about that one. It is like in A Princess of Mars, in which we are informed that on the red planet Barsoom they have nine colors in their spectrum and not seven; I have tried and failed many times to imagine those extra Barsoomian colors.

“What?” my wife asked, sensing my abstraction from the matter at hand.

“I was thinking about the Mars books of Edgar Rice Burroughs,” I said glumly.

“Do they feature ritual genital mutilation?”

“Not that I recall.”

The baby popped off the breast, and sighed, and considered one of the anemone wisps of drifting smoke, like the aftermath of a bursting skyrocket, that I imagined his thoughts to resemble. At seven days he gave evidence of a melancholy or even mournful nature. He sighed again, and so I sighed, thinking that we were about to confirm, in the worst possible way, all the lugubrious ideas about the world that he already seemed to have formed. Then he burrowed back in for another go at his mother.

“If it was a girl,” my wife said, “we would never.”

“Never.”

We had been through this, all of this, before. Every time some brave doctor or grown victim spoke out against the ritual mutilation of girls’ labias in certain subcultures, we were duly outraged.

“It’s not one bit less barbaric than what they do over there,” my wife said. “Not one.”

“Agreed.”

“It’s madness. The more I think about it, the more insane it seems.”

I said I thought that was probably true of everything our religion expected us to do, from burying a pot in the ground because one day a meatball accidentally rolled inside of it, to replacing the hair you had shaved off, out of modesty, with a fabulous-looking five-thousand-dollar wig. In fact, I said, most human social behavior probably fit the formula she had just proposed – for example, neckties. But my observation failed to impress or even, it seemed, to register with my wife. She was gazing down at our little boy with the eyes of a betrayer, filled with pity and tears.

“You have to at least promise me,” she said, “that it’s not going to hurt him.”

As with the first time, we had shopped around the mohel market, looking for a guy who used, or would permit us to use, an anesthetic cream. Traditionally, the only painkiller was a drop of sweet wine introduced between the lips on the wine-soaked tip of a cloth, and a lot of mohelim stuck to that way of doing things. Some of them would suggest giving the boy Tylenol an hour beforehand. And then there were those who prescribed a cream such as Emla. The mohel who was coming tomorrow had given us complicated instructions that involved filling a bottle nipple with the Emla well before the procedure, then fitting it right over the penis, having first enlarged the hole in the tip of the nipple to permit the flow of urine. It was reassuring to think of the entire organ being immersed, steeped in numbing unguent, for hours beforehand. But even the absence of pain, if we could assure it, did not really detract from the fundamental brutality of the business.

“It’s not going to hurt,” I told her, though of course, having never immersed my entire penis in anesthetic cream and then subjected it to minor surgery, I had no idea whether it was going to hurt him or not. That was one of the skills you learned as a father fairly early on, and it had roots as ancient as whatever words Abraham had crafted to lure his son Isaac up that mountainside to the high place where he would bare his beloved child’s breast to the heavens, as he had been commanded to do by the almighty asshole or by the god-shaped madness whose voice was rolling like thunder through his brain. It was not the making of a covenant that the rite called Brit Milah commemorated, but the betrayal of one. Because you promised your children, simply by virtue of having them, and thereafter a hundred times a day, that you would shield them, always and with all your might, from harm, from madness, from men with their knives and their bloody ideas. I supposed it was never too soon for them to start learning what a liar you were.

I reached down and stroked the baby’s cheek.

“It’s not going to hurt,” I promised him, and he looked up at me, his gaze solemn and melancholy, without the slightest idea of what lay in store for him in this world but ready – born ready – to believe me.

D.A.R.E.

One night when she was thirteen, my older daughter opened the discussion at dinner with something that had apparently been troubling her: a problem in the interpretation of rock lyrics. Since she saw the film Across the Universe, her interest in the Beatles had intensified, and lately, I had been fielding many such interpretative queries in my capacity as Senior Fellow in Beatle Studies – deciding whether or not, at the end of “Norwegian Wood,” the singer burns down the girl’s house because she makes him sleep in her bathtub; and working hard not to have to explain to my older son, not quite eleven at the time, what delectable treat was signified in Liverpool slang by the phrase “fish and finger pie.” (So tasty that the singer orders four of them!)

“Dad,” my daughter said, “when he goes ‘I get high with a little help from my friends,’ is he talking about getting high high? Or is he just saying that being around his friends makes him feel really, really, like, happy?”

The ten-year-old was at the kitchen counter pouring himself a glass of milk, but in the instant that preceded my reply, without even looking his way, I could feel him training his detectors on me, his array of receiving dishes all swiveling in my direction. Every time somebody fired one up in a movie, the kid looked simultaneously troubled and intrigued by the sight. He is a clear thinker who likes his questions settled, and I had seen him wrestling for some time with the mixed messages our culture puts out about the pleasures and disasters of drug and alcohol use.

“High high,” I said.

My daughter’s cheeks colored as I met her gaze, in embarrassment and in pleasure, too, I thought, as though her insight had been confirmed in a way that gratified her sense of her own sophistication.

I could remember this moment in my own life, when I was exactly her age and had yet to encounter actual marijuana: the sudden consciousness, a flower of preteen lore and hermeneutics, that the lyrics to Beatles songs were salted with and in some cases constructed entirely from sly and overt references to drug use. Not just “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” or “She Said She Said,” which supposedly re-creates an acid-powered conversation between John Lennon and Peter Fonda, but less obvious numbers like “Girl,” on Rubber Soul, which was, it was claimed, a protracted allegory of marijuana use, with the hissed sighs that punctuate its choruses meant to represent the sound of someone taking a big, long toke. The line Roll up for the mystery tour, I had been told, referred to the rolling of joints.

So I recognized that flush in my daughter’s cheeks. She was a good girl, and I had once been a good boy, and I remembered that simultaneous sense of disapproval and fascination with the lyrical misbehavior of the boys from Liverpool. Thirteen is the age at which you begin to become fully aware of hypocrisy, contradiction, ambiguity, coded messages, subtexts; it is the age, therefore, at which you must begin to attempt to sort things out for yourself, to grab hold, if you can, of any shining thread in the dizzying labyrinth. And there, for me as for my children three decades later, were the Beatles, passing with astonishing and even brutal swiftness from the self-censoring radio-ready plaintext of “Love Me Do” and “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” to the encrypted thickets of songs like “I Am the Walrus” or “Happiness Is a Warm Gun”: the eight-year chronicle in music of the band’s attempt to sort things out for themselves as they came of age, the oeuvre itself a dazzling mass of puzzles and contradictions to be sorted.

“Dad, what does it feel like?” my son said, returning to the table with his glass of milk.

“Getting high?” I said. This time there was no hesitation. I had thought about this conversation, imagined it, planned for it, enough that I ought to have been ready; but even though I had spoken often with my wife (who for many years taught a class at Boalt Hall, UC Berkeley’s law school, called “Legal and Social Implications of the War on Drugs”) about our parental approach to talking about drug use, now that the moment was actually upon me (and she just happened to be out of town), I found that I was not ready at all. I was caught completely off guard. And maybe that’s why I came right out with the truth.

“It feels pretty good,” I said. “It makes you feel like you’re really, uh, being with the people you’re with. It makes you insanely hungry and thirsty. It makes you paranoid. It makes your heart race. It makes you sluggish. It makes you think things are really funny that might not actually be that funny at all.”

“Like dead bodies?” my younger daughter suggested brightly. She was only six years old, but it looked like she was going to be in on this discussion, too.

“Uh, yeah, well, no, more like a bad Elvis movie,” I said. “It makes you have thoughts that seem really, really deep and profound, and then the next day when you remember them, they seem totally lame.”

“I wrote a poem in a dream I had,” the thirteen-year-old said. “The same thing happened with that.”

“Wait,” the ten-year-old said. “Wait. You mean – have you actually smoked marijuana?”

Here it was, the big moment, the one we had all been waiting for, dreading, preparing for years in advance.

“Duh!” the thirteen-year-old informed her brother, doubling down on her proven-worldly views of the role of drugs in modern culture. “Like, every adult over a certain age has done it.”

“Well, not every adult,” I said. “But yes. I have.”

“How many times?” my son said, eyes wide.

So far, even blindsided as I had been by the abrupt onset of this conversation, I hadn’t violated the guiding principle my wife and I had decided on for its eventual proper conduct: I had been honest. But now I had a moment’s pause before replying, unwilling to pronounce those two simple words: one million.

The first person I ever saw smoking pot was my mother, sometime around 1977 or so, sitting in the front seat of her friend Kathy’s car, passing a little metal pipe back and forth before we went in to see a movie at the Westview in Catonsville, Maryland. I have a dim sense that at fourteen I neither disapproved of nor felt any surprise at this behavior, leading me to conclude that my mother already must have told me, prepared me with the information, that she was “experimenting” with pot (because that was all it ever amounted to for her – a brief reagent test conducted within the beaker of her new status as a single woman in the great wild laboratory of the 1970s). If I was shocked by the idea of my mother breaking the law, that shock must have been mitigated by the casualness, and by the lack of shame or embarrassment with which my mother, an otherwise upright, sober, and law-abiding taxpayer, went about it. It appeared to be no big deal for a couple of grown women to smoke a bowl: an innocent, everyday sign of the times. Nevertheless, smoking marijuana remained for years afterward nothing I had any interest in trying myself, not so much because I feared its effects or even because it was against the law but simply because I was a good boy, and as such I looked down my nose with a cosmic, Galactus-sized censoriousness at the kids I knew – stoners, burnouts – who smoked it. I would not have minded breaking the law or getting high, but I could not abide the thought of being bad.

I clung to my increasingly cumbersome and ineffectual goodness, fighting a series of rearguard actions against the increasing presence in my life of rock and roll and sex, until, like the personnel of the U.S. embassy in Saigon leaping to the helicopters, I abandoned it entirely, at once. Early in October of my first term at Carnegie Mellon University, I was taught the rudiments of bong-handling by a team of experts. I lay down on the floor of a dorm room in Mudge Hall, under the light of a single red bulb, and swam through layers of warmth and well-being while an apparently infinite, starry, velvet-bright quantity of wonder was ladled into my ears by Jeff Beck, Jan Hammer and his spacefaring Group.

That was 1980. I smoked marijuana (with odd European forays into the mysteries of hashish) over the course of the next twenty years, never every day, mostly on weekends or when some came around, but at times with all the fierce passion of a true hobbyist. The price went up, and the quality improved so acutely that the nature of the high began to alter without quite changing, like a television picture increasing the resolution of its image. My level of dope-smoking peaked, becoming nearly habitual just after the breakup of my first marriage in 1990, and began to dwindle thereafter as the elevated concentrations of THC (or something) took a toll and I found that getting high often left me feeling apprehensive, hypercritical of myself, and prone to an unwelcome awareness of my life as nothing but a pile of botched and unfinished tasks. Over the course of these pot years I graduated from college, got a master’s degree, wrote a number of novels, paid my bills and my taxes, etc. I was never arrested, never got into any kind of trouble, never broke anything that could not be repaired. Mostly it had been fun, sometimes hugely; sometimes not at all. Marijuana could intensify the sunshine of a perfect summer day, but it could also deepen the gloom of a wintry afternoon; it had bred false camaraderies and drawn my attention to deep flaws and fault lines when what mattered – what matters so often in the course of everyday human life – were the surfaces and the joins.

Be honest, my wife and I had agreed.

“I have smoked it a number of times,” I told my son. “But I don’t do it anymore.”

This was true. Without ceremony or regret, I smoked marijuana for the last time in 2005 – having not smoked any for at least a year before that – when I found myself, stoned out of my brain and very much not following the plot of Stephen Chow’s God of Cookery, unexpectedly called upon to engage in some urgent full-on parenting: There was an abortive sleepover and a necessary stretch of late-night driving to be done. Though I somehow managed to pull it off, gripping the wheel, heart pounding, the world beyond the windshield as trackless and unfathomable as any Jeff Beck guitar solo, I spent the next hour fighting off the knowledge that I was not up to the task, and I vowed that I would never risk putting my children or myself in that position again. On some fundamental level, I was no longer willing to endure, or capable of enjoying, that kind of fun.

“Why did you stop?” those children wanted to know. “Because it’s really illegal?”

“Well, it is really illegal,” I agreed. “In some ways, a lot more illegal than it used to be when I was younger. But that’s not really it. It has to do with, well, with being ready, you know. It’s just not something I’m ready to do anymore. And it’s not something you guys are ready to do, either. Right?”

“Right,” they said at once, with all the firmness and certainty I would have mustered myself in those years before I sailed off into the red light and velvet darkness.

“The truth is,” I told them, then pushed myself to live up to the principle my wife and I had established for contending not only with this issue but with all the other hypocrisies that life as a parent entails. I want to tell you / My head is filled with things to say, as George Harrison once sang, When you’re here / All those words, they seem to slip away. “The truth is that I’m confused about what to tell you,” I said. “But I mostly want us all to tell each other the truth.”

They said that sounded all right to them and that I shouldn’t worry. That’s just what I would have said at their age.

The Memory Hole

Almost every school day, at least one of my four children comes home with art: a drawing, a painting, a piece of handicraft, a construction-paper assemblage, an enigmatic apparatus made from pipe cleaners, sparkles, and clay. And almost every bit of it ends up in the trash. My wife and I have to remember to shove the things down deep, lest one of the kids stumble across the ruin of his or her laboriously stapled paper-plate-and-dried-bean maraca wedged in with the junk mail and the collapsed packaging from a twelve-pack of squeezable yogurt. But there is so much of the stuff; we don’t know what else to do with it. We don’t toss all of it. We keep the good stuff – or what strikes us, in the Zen of that instant between scraping out the lunch box and sorting the mail, as good. As worthier somehow: more vivid, more elaborate, more accurate, more sweated over. A crayon drawing that fills the entire sheet of newsprint from corner to corner, a lifelike smile on the bill of a penciled flamingo. We stack the good stuff in a big drawer, and when the drawer is finally full, we pull out the stuff and stick it in a plastic bin that we keep in the attic. We never revisit it. We never get the children’s artwork down and sort through it with them, the way we do with photo albums, and say “That’s how you used to draw curly hair” or “See how you made your letter E’s with seven crossbars?” I’m not sure why we’re saving it except that getting rid of it feels so awful.

Under the curatorship of my mother, my brother’s and my collected artwork is, if I may say so, a vastly more impoverished archive. From the years preceding high school there is almost nothing at all. The countless scenes of strafing Spitfires taking heavy German ack-ack fire, the corrugated-cardboard-and-foil George Washington hatchets, the clay menorahs (I never did make any dreidels out of clay), the works in crayon resist and papier-mâché and yarn and in media so mixed as to include Cheerios, autumn leaves, and dirt – gone, all of it. Do I care? Does it pain me to have lost forever this irrefutable evidence of my having been, if neither a prodigy nor an embryonic Matisse, a child? If my mother had held on to more of my childhood artwork, would I be happier now? Would the narrative that I have constructed of the nature and course of my childhood be more complete? I guess ultimately, I have no way of answering these questions. It’s like wondering whether sex would be more pleasurable if I had not been worked over by that old Jew with a knife at the age of eight days. How much more pleasurable, really, do I need it to be?

When I run across one of the pieces of artwork that my mother did save – paintings that I made in my junior and senior years of high school, for the most part – the prevailing emotion I experience, with breathtaking vividness, is the acute discontent that I felt at the time of their creation, a dissatisfaction purified of any residual sense of pride or accomplishment. Their flaws of perspective and construction, the places where I cheated or fudged or simply could not pull something off, even a faint tempera-scented whiff of the general miasma of mortification and insufficiency in which I then swam – they all present themselves to my sight and recollection with a force that makes me a little ill.

I’m not trying to excuse the act of throwing away my children’s artwork. The crookedest mark of a colored pencil on the back of a bank-deposit envelope, vaguely in the shape of a fish, is like a bright, stray trace of the boundless pleasure I take in watching my kids interact with the world. The set of processes joining their minds to their fingertips is a source of profound interest and endless speculation, a mystery that, through their artworks, my children endlessly expound. I know that if I live long enough, a time will come when their childhoods will strike me as having been mythically brief. Almost nothing will remain of these days, and they will be women and men, and I will look back on the lost piles of their drawings and paintings and sketches, the cubic yards of rubbings and scratchings consigned to the recycling bin, the reef’s worth of shells, sand, and coral glued to their découpage souvenirs of vacations in Hawaii and Maine, and rue my barbarism. I will be haunted by the memory of the way my younger daughter looks at me when she chances upon a crumpled sheet of paper in the recycling bin, bearing the picture, the very portrait, of five minutes stolen from the headlong rush of their hour in my care: She looks betrayed.

“I don’t know how that got in there,” I tell her. “That was clearly a mistake. What a great dog.”

“It’s a girl kung fu master.”

“Of course,” I say. When she isn’t looking, I throw it away again.

It’s not only her artwork that I’m busy throwing away. Almost every hour that I spend with my children is disposed of just as surely, tossed aside, burned through like money by a man on a spree. The sum total of my clear memories of them – of their unintended aphorisms, gnomic jokes, and the sad plain truths they have expressed about the world; of incidents of precociousness, Gothic madness, sleepwalking, mythomania, and vomiting; of the way light has struck their hair or eyelashes on vanished afternoons; of the stupefying tedium of games we have played on rainy Sundays; of highlights and horrors from their encyclopedic history of odorousness; of the 297,000 minor kvetchings and heartfelt pleas I have responded to over the past eleven years with fury, tenderness, utter lack of interest, or a heartless and automatic compassion – those memories, when combined with the sum total of photographs that we have managed to take, probably add up, for all four of my children, to under 1 percent of everything that we have undergone, lived through, and taken pleasure in together.