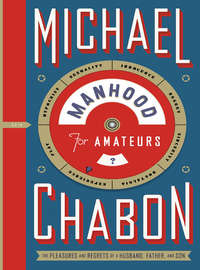

Manhood for Amateurs

The truth is that in every way, I am squandering the treasure of my life. It’s not that I don’t take enough pictures, though I don’t, or that I don’t keep a diary, though iCal and my monthly Visa bill are the closest I come to a thoughtful prose record of events. Every day is like a kid’s drawing, offered to you with a strange mixture of ceremoniousness and offhand disregard, yours for the keeping. Some of the days are rich and complicated, others inscrutable, others little more than a stray gray mark on a ragged page. Some you manage to hang on to, though your reasons for doing so are often hard to fathom. But most of them you just ball up and throw away.

The Binding of Isaac

I was there, in Grant Park, on the night when Barack Obama began to shoulder all the possible meanings of his victory. You could hear it in his voice as the weight of it settled on him, and in the simple, judicious gravity of his language. You could see it in the glint, like the reflection of some awful or awesome vista, that lit his tired eyes. On a giant television screen to the right of the dais we could see what the world was seeing, and we could begin to imagine all the things that for Obama and for all of us were going to change henceforward. It was heady to contemplate, and thrilling, and after such a fierce and interminable campaign, there was also a tremendous sense of relief as we passed from the months of active wishing to this hour of having it be so. But among the most powerful emotions that stirred me as I stood there in the crowd, on that unseasonably warm evening with my son Abraham perched on my shoulders, was sadness. And that caught me a little unawares. I felt guilty about it. I knew I was only supposed to be happy at that moment, thrilled, grave, tired, relieved, duly awestruck – but happy. Yet I couldn’t stop thinking about his two little girls.

Like the rest of the world, even many of those who had (by their own accounts the next morning) voted, connived, pontificated, or railed against Barack Obama, I held my breath as I watched him first walk out to the podium that night with Michelle, Malia, and Sasha. The four of them, dressed in shades of red and black, seemed to catch and hold a different kind of light, the light of history, astonishing and clear. Time stopped, and I was conscious as I have been very few times in my life – the morning of September 11, 2001, was, terribly, another – of seeing something that had never been seen. It was not only the beauty, or the blackness, or the youth of the new first family, or some combination of the three. It was the unmistakable air of mutual engagement the Obamas give off, the sense of being a fully operational – loving, struggling, seeking, adjusting, testing, playing, mythologizing, arguing, rationalizing, celebrating, compromising, affirming, denying – family. I felt that I had never seen a presidential family that was so clearly a working family in the sense of the everyday effort involved. When I was born, there were children in the White House, though they moved out, half orphaned, before I was six months old. I can remember Tricia Nixon’s wedding, and Amy Carter and Chelsea Clinton getting braces or rolling Easter eggs on the White House lawn. But none of those families ever reminded me, ever seemed to reflect – at the fundamental level of daily operations where every great, august, well-reasoned principle and theory you profess or hold dear gets proved or shattered – my own.

With his daughters darting around his long legs, I saw Barack Obama as a father, like me. And I folded my hands behind my son’s knobby back, to bolster him there on my shoulders, and gave his bottom a squeeze, and watched those radiant girls waving and smiling at the quarter-million of us, faces and voices and starry camera flashes, and thought I would never have the nerve or the strength or the sense of mission or the grace or the cruelty to do that to you, kid. There are no moments more painful for a parent than those in which you contemplate your child’s perfect innocence of some imminent pain, misfortune, or sorrow. That innocence (like every kind of innocence children have) is rooted in their trust of you, one that you will shortly be obliged to betray; whether it is fair or not, whether you can help it or not, you are always the ultimate guarantor or destroyer of that innocence. And so, for a moment that night, all I could do was look up at the smiling little Obamas and pity them for everything they did not realize they were now going to lose: My heart broke, and I had this wild wish to undo everything we all had worked and hoped so hard, for so long, to bring about.

And then I noticed the way I seemed to be exempting myself, holding myself aloof, from responsibility for the kind of injury that I imagined Barack Obama had determined to inflict upon his children in the service of his conviction, his calling, his sense of duty, his altruism, his tragic or glorious destiny, and I felt the burden of my son weigh heavier on my own shoulders. You don’t have to become the president of the United States to betray your children. Being a father is an unlimited obligation, one that even the best of us, with the least demanding of children, could never hope to fulfill entirely. Children’s thirst for their fathers can never be slaked, no matter how bottomless and brimming the vessel. I have abandoned my children a thousand times, failed them, left their care and comfort to others, wandered in by telephone or e-mail from the void of a life on the road, issued arbitrary and contradictory commands from my mountaintop when all that was wanted was a place on my lap, absented myself from their bedtime routine on a night when they needed me more than usual, forestalled, deferred, or neglected their needs in the name of something I told myself merited the sacrifice. All that was in the very nature of fatherhood; it came with the territory.

Now, when I looked at Obama, whose own father had taken off when he was still a small boy, never to return, the pity I felt was for him. I hoisted my son higher on my shoulders and thought about his distant ancestor and namesake, armed with the fire and the knife of his great purpose, leading his son up Mount Moriah to pay the price that must be paid for the sacrifice that must be offered.

“Look at him,” I urged my son. “Look at Barack. Look at Malia and Sasha. Abraham, look at them, remember them. You’ll remember this night for the rest of your life.”

“How do you know I won’t forget?” my endlessly, implacably reasoning five-year-old said. He has always been a bit of a contrarian, and he may not have been fully in the spirit of Grant Park that night, either. “Maybe you won’t be there.”

He was right. I won’t be there some day, one day, when he looks back and finds that he still remembers the faraway night on my long-departed shoulders, the night in Chicago when everything began to change, for him and for Malia and Sasha and for the world. But I didn’t tell him that. Let him, let all of us, I thought, hold on to our innocence a little bit longer.

To the Legoland Station

Squares and rectangles. That’s what we had. Squares, rectangles, and wheels with chewy black rubber tires. Sloping red “roof” bricks of which there never seemed to be enough to cover a house. Trees shaped more like real trees than the schematic dendrites you get now. Windows and doors with snap-in glazing: more squares and rectangles. Six colors: basic red, white, blue, yellow, green, and black. And that was it.

Light blue, aquamarine, orange, purple, maroon, gold, silver, plum, pink – pink Legos! – and many shades of gray: Each of the original primary and secondary tones now has at least five variants, enabling the builder of, say, a Jawa Sandcrawler model to re-create the stippling of rust and corrosion in the Sandcrawler’s hull by varying his palette of reds and grays. I still get a funny feeling, a kind of tiny spasm of moral revulsion, when I pick up a teal or lilac Lego. As for shape, Lego “bricks” left behind the orthogonal world years ago for a strange geometry of irregular polygons, a vast bestiary of hybrid pieces, custom pieces, blanks and inverts, clears and pearlescents, freaks that have their raised dots or their gripping tubes on more than one side at a time. And then there are the people – minifigs, as they’re known among Legographers: Frankenstein monsters, American Indians, Jedi knights and pizza chefs, medieval crossbowmen and Vikings, deep-sea divers and bus drivers, Spider-Man, Harry Potter, Allen Iverson – the range of occupations and personalities to be found among the denizens of the Legosphere is so wide and elaborate that perhaps only the brain of an eight-year-old could possibly master it. I remember the sense of disdain I felt toward the cylinder-headed homunculi when minifigs began to be introduced, around the time when my original interest in Legos was waning. They didn’t have the painted faces back then. Their heads were shiny yellow voids. Their arms and legs couldn’t bend, and there was something of the nightmarish, something maimed, about them. But what I most resented about the minifigs was the scale they imposed on everything you built around them. Like Le Corbusier’s humancentric Modulor scale or Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, the minifigs as they proliferated became the measure of all things: Weapons must fit their rigid grip, doorways accommodate the tops of their heads, cockpits accommodate their snap-on asses.

It was this sense of imposition, of predetermined boundaries and contours, of a formulary of play, that I found I most resented when Legos returned to my life, around the time my eldest child turned three. (She was into Indians, or rather, “Indians,” especially Tiger Lily; we bought her a fairly complicated Lego set with war-painted minifigs, horses, tepees, a canoe, a rocky cliff.) But along with the giddy profusion of shapes and colors that had taken place during my long absence from the Legosphere, the underlying purpose of the toys also appeared to have changed.

When I first began to play with them in the late 1960s, Legos retained a strong flavor of their austere, progressive Scandinavian origins. Abstract, minimal, “pure” in form and design, they echoed the dominant midcentury aesthetic, with its emphasis on utility and human perfectibility. They were a lineal descendant of Friedrich Fröbel’s famous “gifts,” the wooden stacking blocks that influenced Frank Lloyd Wright as a child, part mathematics, part pedagogy, a system – the Lego System – by which children could be led to infer complex patterns from a few fundamental principles of interrelationship and geometry. They also made, and make to this day, a strong claim on a kid’s senses, snapping together and coming apart with a satisfying dual appeal to the ear and the fingers. They presented the familiar objects one constructed with them – airplanes, houses, cars, faces – on a quirky grid, the world dissolved or simplified into big, chunky pixels.

In their limited repertoire of shapes and the absolute, even cruel, set of axioms governing the way they could and couldn’t be arranged, Lego structures emphatically did not present – and in playing with them, you never hoped for – the appearance of reality. A Lego construction was not a scale model. It was an idealization, an approximation, your best version of the thing you were trying to make. Any house, any town, you built from Legos, with its airport and tramline and monorail, trim chimneys and grids of grass, automatically took on a certain social-democratic tidiness, even sterility (one of the notable qualities of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, the material from which Lego bricks are made, is that it is sterile).

Orderly, functional, utopian, half imaginary, abstract, primary-colored – when I visited Helsinki a few years back, I felt as if I recognized it, the way you recognize a place from a dream.

By the late nineties, when my wife and I bought that first Indian set, abstraction was dead. Full-blown realism reigned supreme in the Legosphere. Legos were sold in kits that enabled one to put together – at fine scales, in detail made possible by a wild array of odd-shaped pieces – precise replicas of Ferrari Formula 1 racers, pirate galleons, jet airplanes. Lego provided not only the standard public-domain play environments supplied by toy designers of the past fifty to a hundred years – the Wild West, the Middle Ages, jungle and farm and city street – but also a line of licensed Star Wars kits, the first of many subsequent ventures into trademarked, conglomerate-owned, pre-imagined environments. Instead of the printed booklets I remembered, featuring suggestions for the kinds of things you might want to make from your box of squares and rectangles, the new kits came encumbered with fat, abstruse, wordless manuals that laid out, panel after numbered panel and page after page, the steps that must be followed if one hoped – and after all, why else would you nudge your dad into buying it for you? – to end up with a landspeeder just like Luke Skywalker’s (only smaller). Where Lego-building had once been open-ended and exploratory, it now had far more in common with puzzle-solving, a process of moving incrementally toward an ideal, pre-established, and above all, a provided solution.

I resented this change. When my son and I finished putting together a TIE interceptor or Naboo starfighter, usually after several weeks of struggle, a half-deranged search for one tiny black chip of sterile styrene the size of his pinkie nail, and two or three bouts of prolonged despair, the resulting object was so undeniably handsome, and our investment of time in building it so immense, that the thought of playing with it, let alone ever disassembling it, was anathema. But more than the inherent difficulty – which, after all, is an important aspect of puzzle-solving, or the shift from exploration to reproduction – I resented the authoritarian nature of the new Lego. Though I admired and enjoyed Toy Story (1995), the film has always been tainted for me by its subtext of orthodoxy: its implied assertion that there is a right way and a wrong way to play with your toys. Andy, the young hero of Toy Story, uses his toys more or less the way their manufacturers intended – cowboys are cowboys; Mr. Potato Head, with his “angry eyes,” is a suitable mustachioed villain – while the most telling sign that we are to take Sid, the quasi-psychotic neighbor kid, as a “bad boy” is that he hybridizes and “breaks the rules” of orderly play, equipping an Erector-set spider, for example, with a stubbly doll’s head. Sid is mean, cruel, heartless, crazy: You can tell because he put his wrestler doll in a dress. A similar orthodoxy, a structure of control and implied obedience to the norms of the instruction manual and of the implacable exigencies of realism itself, seemed to have been unleashed, like the Dark Side of the Force, in the once bright Republic of Lego.

But I should have had more faith in my children, and in the saving power of the lawless imagination. Like all realisms, Lego realism was doomed. In part, this was an inevitable result of the quirks and limitations inherent in the Lego System, with the distortions that its various techniques of interlocking create. The addition of painted faces and elaborately modeled headgear, weapons, and accoutrements ultimately did little to diminish the fundamental silliness of the minifig; as with CGI animation, the technology falls down at the human form. In depicting people, it makes compromises that weaken the intended realism of the whole. But the technical limitations are only part of the greater failure of realism – defined as accuracy, precision, faithfulness to experience – to live up to the disorder, the unlikeliness, and the recombinant impulse of imagined experience.

Kids write their own manuals in a new language made up of the things we give them and the things that derive from the peculiar wiring of their heads. The power of Lego is revealed only after the models have been broken up or tossed, half finished, into the drawer. You sit down to make something and start digging around in the drawer or container, looking for a particular brick or axle, and the Legos circulate in the drawer with a peculiarly loud crunching noise. Sometimes you can’t find the piece you’re looking for, but a gear or a clear orange cone or a horned helmet catches your eye. Time after time, playing Legos with my kids, I would fall under the spell of the old familiar crunching. It’s the sound of creativity itself, of the inventive mind at work, making something new out of what you have been given by your culture, what you know you will need to do the job, and what you happen to stumble on along the way.

All kids – the good ones, too – have a psycho tinge of Sid, of the maker of hybrids and freaks. My children have used aerodynamic, streamlined bits and pieces of a dozen Star Wars kits, mixed with Lego dinosaur jaws, Lego aqualungs, Lego doubloons, Lego tibias, to devise improbably beautiful spacecraft far more commensurate than George Lucas’s with the mysteries of other galaxies and alien civilizations. They have equipped the manga-inspired Lego figures with Lego ichthyosaur flippers. When he was still a toddler, Abraham liked to put a glow-in-the-dark bedsheet-style Lego ghost costume over a Lego Green Goblin minifig and seat him on a Sioux horse, armed with a light saber, then make the Goblin do battle with a minifig Darth Vader, mounted on a black horse, armed with a bow and arrow. That is the aesthetic at work in the Legosphere now – not the modernist purity of the early years or the totalizing vision behind the dark empire of modern corporate marketing but the aesthetic of the Lego drawer, of the mash-up, the pastiche that destroys its sources at the same time that it makes use of and reinvents them. You churn around in the drawer and pull out what catches your eye, bits and pieces drawn from movies and history and your own fancy, and make something new, something no one has ever seen or imagined before.

The Wilderness of Childhood

When I was growing up, our house backed onto woods, a thin two-acre remnant of a once mighty Wilderness. This was in a Maryland city where the enlightened planners had provided a number of such lingering swaths of green. They were tame as can be, our woods, and yet at night they still filled with unfathomable shadows. In the winter they lay deep in snow and seemed to absorb, to swallow whole, all the ordinary noises of your body and your world. Scary things could still be imagined to take place in those woods. It was the place into which the bad boys fled after they egged your windows on Halloween and left your pumpkins pulped in the driveway. There were no Indians in those woods, but there had been once. We learned about them in school. Patuxent Indians, they’d been called. Swift, straight-shooting, silent as deer. Gone but for their lovely place names: Patapsco, Wicomico, Patuxent.

A minor but undeniable aura of romance was attached to the history of Maryland, my home state: refugee Catholic Englishmen, cavaliers in ringlets and ruffs; pirates, battles, the sack of Washington, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Harriet Tubman, Antietam. And when you went out into those woods behind our house, you could feel all that, all that history, those battles and dramas and romances, those stories. You could work it into your games, your imaginings, your lonely flights from the turmoil or torpor of your life at home. My friends and I spent hours there, braves, crusaders, commandos, blues and grays.

But the Wilderness of Childhood, as any kid could attest who grew up, like my father, on the streets of Flatbush in the forties, had nothing to do with trees or nature. I could lose myself on vacant lots and playgrounds, in the alleyway behind the Wawa, in the neighbors’ yards, on the sidewalks. Anywhere, in short, I could reach on my bicycle, a 1970 Schwinn Typhoon, Coke-can red with a banana seat, a sissy bar, and ape-hanger handlebars. On it I covered the neighborhood in a regular route for half a mile in every direction. I knew the locations of all my classmates’ houses, the number of pets and siblings they had, the brand of Popsicle they served, the potential dangerousness of their fathers. Matt Groening once did a great Life in Hell strip that took the form of a map of Bongo’s neighborhood. At one end of a street that wound among yards and houses stood Bongo, the little one-eared rabbit boy. At the other stood his mother, about to blow her stack – Bongo was late for dinner again. Between Mother and Son lay the hazards – labeled ANGRY DOGS, ROVING GANG OF HOOLIGANS, GIRL WITH A CRUSH ON BONGO – of any journey through the Wilderness: deadly animals, antagonistic humans, lures and snares. It captured perfectly the mental maps of their worlds that children endlessly revise and refine. Childhood is a branch of cartography.

Most great stories of adventure, from The Hobbit to Seven Pillars of Wisdom, come furnished with a map. That’s because every story of adventure is in part the story of a landscape, of the interrelationship between human beings (or Hobbits, as the case may be) and topography. Every adventure story is conceivable only in terms of the particular set of geographical features that in each case sets the course, literally, of the tale. But I think there is another, deeper reason for the reliable presence of maps in the pages, or on the endpapers, of an adventure story, whether that story is imaginatively or factually true. We have this idea of armchair traveling, of the reader who seeks in the pages of a ripping yarn or a memoir of polar exploration the kind of heroism and danger, in unknown, half-legendary lands, that he or she could never hope to find in life. This is a mistaken notion, in my view. People read stories of adventure – and write them – because they have themselves been adventurers. Childhood is, or has been, or ought to be, the great original adventure, a tale of privation, courage, constant vigilance, danger, and sometimes calamity. For the most part the young adventurer sets forth equipped only with the fragmentary map – marked HERE THERE BE TYGERS and MEAN KID WITH AIR RIFLE – that he or she has been able to construct out of a patchwork of personal misfortune, bedtime reading, and the accumulated local lore of the neighborhood children.

A striking feature of literature for children is the number of stories, many of them classics of the genre, that feature the adventures of a child, more often a group of children, acting in a world where adults, particularly parents, are completely or effectively out of the picture. Think of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, The Railway Children, or Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy presents a chilling version of this world in its depiction of Cittagazze, a city whose adults have all been stolen away. Then there is the very rich vein of children’s literature featuring ordinary contemporary children navigating and adventuring through a contemporary, nonfantastical world that is nonetheless beyond the direct influence of adults, at least some of the time. I’m thinking the Encyclopedia Brown books, the Great Brain books, the Henry Reed and Homer Price books, the stories of the Mad Scientists’ Club, a fair share of the early works of Beverly Cleary. As a kid, I was extremely fond of a series of biographies, largely fictional, I’m sure, that dramatized the lives of famous Americans – Washington, Jefferson, Kit Carson, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Daniel Boone – when they were children. (Boys, for the most part, though I do remember reading one about Clara Barton.) One element that was almost universal in these stories was the vast amounts of time the famous historical boys were alleged to have spent wandering with bosom companions, with friendly Indian boys or a devoted slave, through the once mighty wilderness, the Wilderness of Childhood, entirely free of adult supervision.

Though the wilderness available to me had shrunk to a mere green scrap of its former enormousness, though so much about childhood had changed in the years between the days of young George Washington’s adventuring on his side of the Potomac and my own suburban exploits on mine, there was still a connectedness there, a continuum of childhood. Eighteenth-century Virginia, twentieth-century Maryland, tenth-century Britain, Narnia, Neverland, Prydain – it was all the same Wilderness. Those legendary wanderings of Boone and Carson and young Daniel Beard (the father of the Boy Scouts of America), those games of war and exploration I read about, those frightening encounters with genuine menace, far from the help or interference of mother and father, seemed to me at the time – and I think this is my key point – absolutely familiar to me.