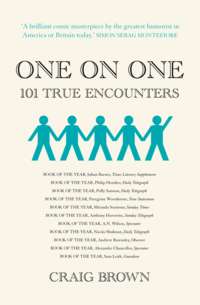

One on One

Afterwards, Jackson is to have a private meeting with the Reagans, along with one or two children of staff members. But when he is ushered into the Diplomatic Reception Room, he is confronted by seventy-five adults.

He turns on his heels, running down the hall into the rest room off the Presidential Library. He locks the door, and refuses to come out. ‘They said there would be kids. But those aren’t kids!’ he protests to Frank Dileo, his manager.

Dileo has a word with a White House aide, who immediately rounds on an assistant. ‘If the First Lady gets a load of this, she’s going to be mad as hell. Now you go get some kids in here, damn it.’

Dileo shouts through the rest-room door, ‘It’s OK, Michael. We’re going to get some kids.’

‘You’ll have to clear all those adults out of there before I come out,’ demands Jackson.

An aide runs into the Reception Room. ‘OK, out! Everybody out!’ A member of Jackson’s entourage arrives in the rest room. ‘Everything is OK.’

‘Are you sure?’ asks Michael.

At this point, Frank Dileo grows edgy. ‘OK, Mike, outta there. I mean it.’

Michael Jackson returns to the freshly vacated Reception Room. A handful of children are waiting. While he signs a copy of Thriller for the Transport Secretary, the Reagans arrive. They usher Jackson into the Roosevelt Room to meet a few more aides and their children.

As Jackson talks to the children, Nancy Reagan whispers to one of his staff, ‘I’ve heard he wants to look like Diana Ross, but looking at him up close, he’s so much prettier than she is. Don’t you agree? I mean, I just don’t think she’s that attractive, but he certainly is.’

Jackson’s employees are forbidden from discussing their employer, so he does not reply.

‘I just wish he would take off those sunglasses,’ continues Mrs Reagan, adding, ‘Tell me, has he had any surgery on his eyes?’

There is still no reply. ‘Certainly his nose has been done,’ whispers Mrs Reagan, peering hard at Jackson, who is now talking to her husband. ‘More than once, I’d say. I wonder about his cheekbones. Is that make-up, or has he had them done too? It’s all so peculiar, really. A boy who looks just like a girl, who whispers when he speaks, wears a glove on one hand and sunglasses all the time. I just don’t know what to make of it.’ She lifts her eyes to the ceiling and shakes her head.

The Jackson aide begins to think it may be rude to say nothing at all to the First Lady. ‘Listen, you don’t know the half of it,’ he says, with a conspiratorial smile. But the First Lady reacts as though she disdains such idle gossip.

‘Well, he is talented. And I would think that’s all that you should be concerned about,’ she snaps.

NANCY REAGAN

DISAPPOINTS

ANDY WARHOL

The White House, Washington DC

October 15th 1981

‘The funny thing about movie people,’ says Andy Warhol to the First Lady over tea in the White House, ‘is that they talk behind your back before you even leave the room.’

Nancy Reagan’s eyes, already preternaturally wide, grow still wider. She looks at Warhol as though he were unbalanced.

‘I am a movie person, Andy,’ she replies.

The interview has been stiff throughout. Mrs Reagan never reacts well to criticism, and can spot it from a great distance. It is written in her stars. ‘Cancers tend to be intuitive, vulnerable, sensitive and fearful of ridicule – all of which, like it or not, I am,’ she explains in her autobiography. ‘The Cancer symbol is the crab shell: Cancers often present a hard exterior to the world, which hides their vulnerability. When they’re hurt, Cancers respond by withdrawing into themselves. That’s me all right.’

Warhol himself has been notably crab-like in his advance on the Reagans. Two months before the 1981 presidential election, he befriended the Reagans’ son Ronald Junior, then their daughter Patti. Both sides are happy: the younger Reagans mix with the most famous artist in America, and in turn Warhol mixes with America’s imminent first family. Warhol likes Ronald Junior. ‘He turned out to be a really nice kid. God, he was so sweet … and he’s very smart. Lispy and cute.’ At their first lunch together, Warhol is tongue-tied. ‘I didn’t know what to talk to him about. I was too shy and he was too shy.’ Warhol finds himself asking an awkward question about whether or not his father dyes his hair. Ronald Junior tries to change the subject. His mother, Nancy, is, he tells Warhol, ‘very sweet and very adorable’.

Warhol seizes the moment. ‘So then I got sneaky and brought Ordinary People up, and I told him how much I hated Mary Tyler Moore, that after I saw the movie if I saw her on the street I’d just kick her. And at that point he was almost going to say something about Nancy, but then somehow he got the drift of it and changed the subject. Because I think the mother in Ordinary People is just like Mrs Reagan. Really cold and shrewd.’

They discuss what to order. Warhol tells Ronald Junior that he has never eaten frogs’ legs, ‘and he was so sweet he ordered them just so I could try it. He’s really sweet, a beautiful body and beautiful eyes. But he just doesn’t have a pretty nose. It’s too long.’

Two weeks later, Patti Davis, Ronald Junior’s older sister, drops by the Interview office. ‘She looked sort of pretty to me, but then looking at her later on the video, how could these kids have missed their parents’ good looks? I mean, Dad was so gorgeous.’

Between Ronald Reagan’s election and his inauguration, Andy Warhol goes out with Ronald Reagan Junior and his wife Doria to see the movie Flash Gordon. By the end of the evening, he has given Doria a job on Interview magazine.

Warhol doesn’t encounter Nancy Reagan until March 1981, when, by chance, he spots her eating in the same restaurant. ‘We were leaving and didn’t want to go by the President’s table because it was too groupie-ish – everybody else was stopping at the table – so we went the other way, but then they called us over. Jerry Zipkin was yelling, and I met Mrs Reagan, and she said, “Oh you’re so good to my kids.”’

The possibility of an interview with Nancy Reagan is mooted in September 1981. By now Nancy has taken to ringing Warhol’s sidekick Bob Colacello at the office, fussing about Ron and Doria, ‘causing no end of envy to Andy’. Colacello negotiates with the White House for an interview with Mrs Reagan: they give their approval, thinking it might lighten her imperious image. But, perhaps sensing Colacello has overtaken him on this particular social ladder, Warhol affects to pooh-pooh the idea. ‘I think she is too old and it’s old-fashioned. We should have younger people. What is there to ask her? About her movie career? Oh, it’ll never happen anyway.’

But it does. A month later, Warhol and Colacello leave for Washington. Colacello warns Warhol not to ask her any ‘sex questions’. This upsets Warhol. ‘I just couldn’t believe him. I mean, I just couldn’t believe him. Did he think I was going to sit there and ask her how often do they do it?’

The two of them, plus Doria, arrive early at the White House and are placed in a reception room. There they remain: when the First Lady arrives, she fails to lead them to somewhere more grand or more intimate. Warhol, ever-alert to matters of status, is affronted; a waiter brings them each a glass of water, and Warhol is further affronted.

The interview never really gets going. ‘We talked about drug rehabilitation, and it was boring. I made a couple of mistakes but I didn’t care because I was still so mad at being told by Bob not to ask sex questions.’

Soon, it is all over. Before ushering them out, Nancy Reagan gives Doria a piece of Tupperware (‘not wrapped up or anything’) and socks for Ron Junior. Colacello tells Nancy what a good mother she is, and asks what they are doing for Christmas. Nancy says they will stay at the White House, ‘because nobody ever stays at the White House’.

Warhol leaves feeling he has been snubbed. A glass of water! When he gets home, his phone is ringing. ‘It was Brigid asking me what kind of tea Mrs Reagan served us, and then I started thinking and I got madder. I mean, she could have put on the dog – she could have done it in a good room, she could have used the good china! I mean, this was for her daughter-in-law, she could have done something really great for this interview but she didn’t. I got madder and madder thinking about it.’

ANDY WARHOL

BLANKS

JACKIE KENNEDY

1040 Fifth Avenue, New York

December 20th 1978

Somehow, Andy Warhol has no luck with Presidents or First Ladies. They never seem to hit it off. After a party for Newsweek in 1983, he observes, ‘It was a boring party. No stars. Just Nancy Reagan and President and Mrs Carter.’

But they have their uses. On November 22nd 1963, he was walking through Grand Central Station when the news came through that President Kennedy had been assassinated. Warhol paused to absorb this and then, in a matter-of-fact manner, said to his assistant, ‘Well, let’s get to work.’

Within months, he had produced any amount of pictures of Jackie Kennedy, some adapted from a photograph of her smiling just before her husband was shot, some from photographs of her at his funeral, others a combination of the two.

As the years roll by, the paths of America’s most famous widow and America’s most famous artist cross on a regular basis. He is mesmerised by her fame. Possibly as a result, she is often standoffish towards him.* This makes him touchy. In 1977, Warhol is invited to a fundraising dinner Jackie has organised. ‘The dinner was a horror. They put us at such a nothing nobody table,’ he records in his diary. ‘So here we were in this room where we didn’t even recognise anybody except each other and this girl comes over to me and says, “I know you have a camera, and you can take pictures of everyone here except Mrs Onassis.”’ A few minutes later, Warhol enters the main room and finds not only that ‘there was everybody we knew’, but ‘there were 4,000 photographers taking pictures of Jackie. And that horrible girl had come over to tell me I couldn’t!’

The following year, Warhol is irritated to be told that Diana Vreeland doesn’t think he is avant-garde any more, and Jackie doesn’t either. That November, he hears that Jackie has thrown a party without inviting him. ‘Robert Kennedy Jr told Fred that they had a big question about whether to invite us and decided not to. Jackie really is awful, I guess.’

A week later, things look up. He receives an invitation to Jackie’s Christmas party. Warhol invites his friend Bob Colacello. They arrive late. ‘Warren Beatty and Diane Keaton were there and Bob heard – overheard – Jackie saying that something Warren did in the hall was “disgusting”, but we were never able to find out what it was.’

Over dinner at Mortimer’s afterwards, someone says Beatty has had sex with Jackie. Bianca Jagger says Warren has probably just made it up, because he made up that he slept with her, and when she saw him in the Beverly Wilshire she embarrassed him by screaming, ‘Warren, I hear you say you’re fucking me. How can you say that when it’s not true?’

Then Bianca says that Warren has a big cock, and Steve asks how would she know, and she says that all her girlfriends have slept with him. Colacello is ‘in heaven’ because Jackie is so nice to him, even sharing her glass of Perrier with him when the butler forgot to bring his, and saying, ‘It’s ours.’

But the next day, Jackie has turned turtle. She calls Warhol three or four times at his office. ‘But I didn’t call back, because the messages were complicated – they were like, “Call me at this number after 5.30, or before 4.00 if it’s not raining.”’ Finally, she catches him at home. She is frosty. ‘She sounded so tough. She said, “Now Andy, when I invited you, I invited you – I didn’t invite Bob Colacello.”’ She complains that Colacello ‘writes things’. This leads Warhol to suspect that ‘something must have happened there that she doesn’t want written about. She was thinking about it all day, I guess.’ Could she be referring to the disgusting thing Warren Beatty did in her hall?

She punishes Warhol for his tardiness and his uninvited guest by asking her friends not to invite him to their parties. Warhol gets wind of his exclusion; their relationship deteriorates further. She never invites him to another Christmas party. It rankles. He records each fresh omission in his diary. ‘Shook hands with Jackie O.,’ he writes after attending a black-tie charity do at the Helmsley Palace. ‘She never invited me to her Christmas party again, so she’s a creep. And now I wouldn’t go if she did. I’d tell her to go mind her own business. I mean, I’m the same age, so I can tell her off. Although I do feel like she’s older than me. But then, I feel like everybody’s older than me.’

Warhol never quite gets over his exclusion from Jackie’s party list. In 1985, he is still fulminating. ‘I don’t understand why Jackie O. thinks she’s so grand that she doesn’t owe it to the public to have another great marriage to somebody big. You’d think she’d want to scheme and connive to get into history again.’

On Saturday, April 26th 1986, he attends the Cape Cod wedding of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Maria Shriver,* and notes, ‘Jackie never smiled at anyone, she was a sourpuss.’ At the reception, he blanks her. ‘I didn’t look at Jackie, I felt too funny.’ The two of them never see each other again. Less than a year later, Andy Warhol dies unexpectedly, following an operation to remove his gall bladder.

Twenty-two years after his death, archivists are sifting through 610 cardboard boxes, filing cabinets and a shipping container full of the belongings of Andy Warhol. They find, among much else, a piece of old wedding cake, various empty tins of chicken soup and $17,000 in cash. They also come across a photograph of Jackie Kennedy swimming naked. It is signed by her, ‘For Andy, with enduring affection, Jackie Montauk’ – a reference to Warhol’s estate on Long Island. No one knows how on earth it came to be there, or the story behind it; but it undoubtedly dates from a time before their falling-out in 1978.

JACKIE KENNEDY

IS ILL-AT-EASE WITH

HRH QUEEN ELIZABETH II

Buckingham Palace, London

June 5th 1961

It is barely four months since President Kennedy’s inauguration. Mrs Kennedy is still finding her feet.

Jackie is unsure of herself. In public, she smiles and waves. In private, she bites her nails and chain smokes. She is prone to self-pity. She is overheard saying, ‘Oh, Jack, I’m so sorry for you that I’m such a dud,’ to which Kennedy replies, ‘I love you as you are.’ Is each of them telling only half the truth?

Socially, she is an awkward mix of the gracious and the paranoid. ‘At one moment, she was misunderstood, frustrated and helpless. The next moment, without any warning, she was the royal, loyal First Lady to whom it was almost a duty to bow, to pay medieval obeisance,’ is the way her English friend Robin Douglas-Home puts it. ‘Then again, without any warning, she was deflating someone with devastating barbs for being such a spaniel as to treat her as the First Lady and deriding the pomp of politics, the snobbery of the social chamber.’

But now, on their whistle-stop tour of Europe, Jackie suddenly appears formidable. The French take to her as one of their own: born a Bouvier, she has French ancestry, and spent a year at the Sorbonne. She speaks fluent French and has arrived with a wardrobe of clothes specially designed for her by Givenchy. At a banquet at Versailles, President de Gaulle greets her by saying, ‘This evening, Madame, you are looking like a Watteau.’*

The political editor of Time reports that, ‘Thanks in large part to Jackie Kennedy at her prettiest, Kennedy charmed the old soldier into unprecedented flattering toasts and warm gestures of friendship.’ At a press conference, President Kennedy says, ‘I do not think it altogether inappropriate to introduce myself … I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris, and I have enjoyed it.’

Over dinner in Vienna, Jackie Kennedy charms Mr Khrushchev. As the evening unwinds, the Soviet Chairman draws his chair closer and closer to her. He compliments her on her white evening gown, and their subsequent conversation encompasses everything from dogs in space to folk dances in Ukraine. At the end of it, Khrushchev promises to send her a puppy as a present.

But the next morning, Khrushchev is back to his grumpy old self. He has no interest in charming the President, still less in being charmed by him. Kennedy emerges from their meeting feeling humiliated. On the flight from Vienna to London, both Kennedys appear downhearted, their gloom increased by the President’s perennial back problems. Their doctor administers drugs to buck them both up: amphetamines and vitamins for the First Lady and novocaine for the President, who is also taking the powerful painkiller Demerol.

In London the next day, the President informs the avuncular British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, of the battering he has received. ‘The President was completely overwhelmed by the ruthlessness and barbarity of the Russian Chairman,’ records Macmillan. ‘It reminded me in a way of Lord Halifax or Neville Chamberlain trying to hold a conversation with Herr Hitler. For the first time in his life Kennedy met a man who was impervious to his charm.’

In the morning, they attend the christening of Jackie’s niece Christina Radziwill. From there, they go to an informal lunch with the Prime Minister and a number of friends and relations, including the Ormsby-Gores and the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire. The Duchess, an old friend of the President,* has mixed feelings about Jackie. ‘She is a queer fish. Her face is one of the oddest I ever saw. It is put together in a very wild way,’ she observes to her old friend Patrick Leigh Fermor.

That evening, the Kennedys attend a dinner at Buckingham Palace. It proves a minefield. The guest list has been the subject of negotiation: traditionally, divorcees are not invited, so the Queen has been reluctant to welcome Jackie’s sister Princess Lee Radziwill, who is on her second marriage, or her husband Prince Stanislaw Radziwill, who is on his third. Under pressure, she relents, but, by way of retaliation, singularly fails to invite Princess Margaret or Princess Marina, both of whose names Jackie has put forward. Jackie’s old paranoia returns: she sees it as a plot to do her down. ‘The Queen had her revenge,’ she confides to Gore Vidal.* ‘No Margaret, no Marina, no one except every Commonwealth minister of agriculture they could find.’ Jackie also tells Vidal that she found the Queen ‘pretty heavy-going’. (When Vidal repeats this to Princess Margaret some years later, the Princess loyally explains, ‘But that’s what she’s there for.’)

Over dinner, Jackie continues to feel awkward, even persecuted. ‘I think the Queen resented me. Philip was nice, but nervous. One felt absolutely no relationship between them.’

The Queen asks Jackie about her visit to Canada. Jackie tells her how exhausting she found being on public view for hours on end. ‘The Queen looked rather conspiratorial and said, “One gets crafty after a while and learns how to save oneself.”’† According to Vidal (who is prone to impose his own thoughts on others), Jackie considers this the only time the Queen seems remotely human.

After dinner, the Queen asks if she likes paintings. Yes, says Jackie, she certainly does. The Queen takes her for a stroll down a long gallery in the palace. They stop in front of a Van Dyck. The Queen says, ‘That’s a good horse.’ Yes, agrees Jackie, that is a good horse. From Jackie’s account, this is the extent of their contact with one another, but others differ. Dinner at Buckingham Palace, writes Harold Macmillan in his diary that night, is ‘very pleasant’.

Nine months later, Jackie pays another visit to the Queen at Buckingham Palace, this time by herself. She is more in the swing of things now. ‘I don’t think I should say anything about it except how grateful I am and how charming she was,’ she tells the television cameras as she makes her escape.

HRH QUEEN ELIZABETH II

ATTENDS

THE DUKE OF WINDSOR

4, route du Champ d’Entraînement, Bois de Boulogne, Paris

May 18th 1972

The Queen is to pay a state visit to Paris to ‘improve the atmosphere’ before Britain’s entry into the Common Market. But before the visit takes place, word arrives at Buckingham Palace that her uncle David, once King Edward VIII, now the Duke of Windsor, has throat cancer, and is days from death.

The Queen’s Private Secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, contacts the British Ambassador in Paris, Sir Christopher Soames, who in turn arranges a meeting with Jean Thin, the Duke of Windsor’s doctor. The Ambassador comes straight to the point. Dr Thin recalls: ‘He told me bluntly that it was all right for the Duke to die before or after the visit, but that it would be politically disastrous if he were to expire in the course of it. Was there anything I could do to reassure him about the timing of the Duke’s end?’

Unversed in royal protocol, Thin is taken aback. He can offer no such reassurance. The Duke may die before, during or after his niece’s state visit to France, but he is not in the business of making predictions. The Palace is put out. Will the Duke prove as much of a nuisance in death as in life? As it turns out, the prospect of the Queen’s visit gives the Duke a new lease of life: more than ever, he seems determined to cling on.

And so he does. He is still alive when the royal party lands at Orly Airport on May 15th. Each evening, Sir Christopher telephones Dr Thin to see how his patient is coming along. Dr Thin reports that His Royal Highness is unable to swallow and on a glucose drip, but still intent on welcoming his monarch.

At 4.45 p.m. on May 18th, the royal entourage arrives after a day at the Longchamp races. The Duchess of Windsor greets the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh and the Prince of Wales with a succession of shaky curtseys, ushering them into the orchid-laden drawing room for tea. For the next fifteen minutes, no one mentions the Duke of Windsor’s health. ‘It was as if they were pretending that David was perfectly well,’ the Duchess says later. She complains that the Queen was ‘not at all warm’, though she may simply be irritated by the Windsors’ jumpy pugs.

The only member of the royal visitors to have been here before is the Prince of Wales, who called by last October, hoping to patch things up between his black-sheep uncle and the rest of the family. The very next month, Uncle David was diagnosed with cancer, so the Prince’s account in his diary of his visit provides a glimpse, albeit a sniffy glimpse, into the Windsors’ life as it was lived, not long ago: ‘Upon entering the house I found footmen and pages wearing identical scarlet and black uniforms to the ones ours wear at home. It was rather pathetic seeing that. The eye then wandered to a table in the hall on which lay a red box with “The King” on it … The whole house reeks of some particularly strong joss sticks and from out of the walls came the muffled sound of scratchy piped music. The Duchess appeared from a host of the most dreadful American guests I have ever seen. The look of incredulity on their faces was a study and most of them were thoroughly tight. One man shook hands with me twice, muttered something incomprehensible in French with a strong American accent and promptly collapsed into the arms of a strategically placed black footman.’

The Duchess (dismissed by Charles after their meeting as ‘a hard woman – totally unsympathetic and somewhat superficial’) leads the Queen up the stairs, where the Duke is sitting in a wheelchair, crisply dressed for the occasion in a blue poloneck and blazer. These garments conceal a drip tube, which emerges from the back of the collar and then swoops down to flasks concealed behind a curtain. He has shrivelled to ninety pounds. As the Queen enters, he struggles to his feet and, with some effort, manages to lower his neck in a bow. Dr Thin worries that this may cause the drip to pop out, but all is well, and it stays put.