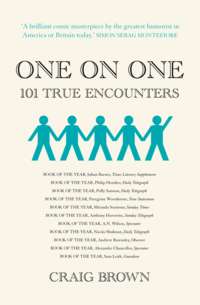

One on One

An awkward moment comes when the old deaf woman suddenly says, ‘Did I hear the word “whisky”?’

‘Do you want one?’ asks Waugh.

‘More than anything in the world.’

‘I’ll get you some.’

But at this point the Portuguese poet steps in. He nudges Waugh and says, ‘It would be disastrous.’ So Waugh persuades her to stick with the white wine. Repeating the words of the Portuguese poet, he explains to Guinness that ‘We couldn’t face another disaster from that quarter.’

Over lunch, Guinness tipsily shares his few remaining theological anxieties with the blond English youth and the Portuguese poet. ‘Would we have to drink the Pope’s health? If Edith died on the spot would she go straight to heaven? And would that be a case for ecclesiastical rejoicing or worldly and artistic distress?’ A great deal is drunk; the following morning, try as he may, Guinness cannot recollect any of them leaving the table.

EVELYN WAUGH

WRONG-FOOTS

IGOR STRAVINSKY

The Ambassador Hotel, Park Avenue, New York

February 4th 1949

Evelyn Waugh claims to dislike all music, with the possible exception of plainchant. This does not bode well for Igor Stravinsky as he prepares to meet him in New York. He has already been warned by Aldous Huxley that Waugh can be ‘prickly, pompous, and downright unpleasant’. But he is an admirer of Waugh’s writing, particularly his talent for dialogue and the naming of characters (Dr Kakaphilos; Father Rothschild, S.J.), and is pleased when a friend arranges a meeting.

Stravinsky spent last night in the more congenial company of Vladimir Nabokov, W.H. Auden and George Balanchine, playing them his draft score of Act 1 of The Rake’s Progress. As usual, he found himself a little irritated by Auden’s tendency to talk during any performance, but this is small fry compared to what lies ahead: Waugh is, after all, notoriously prickly.

‘Why does everybody except me find it so easy to be nice?’ asks the distracted Gilbert Pinfold in Waugh’s most autobiographical novel.* Tom Driberg identifies this as ‘a true outcry’ from Pinfold’s creator. At the age of only forty-five, Waugh has somehow boxed himself into the character of a grumpy old curmudgeon: Penelope Fitzgerald sums up the social message he wishes to convey as: I am bored, you are frightened.

His rudeness has no age limit. When Ann Fleming brings her uninvited three-year-old son to tea at the Grand Hotel, Folkestone, Waugh is so annoyed that he puts ‘his face close to the child’s, dragging down the corners of eyes and mouth with forefingers and thumbs, producing an effect of such unbelievable malignity that the child shrieked with terror and fell to the floor’. Fleming retaliates by giving Waugh’s face a hard slap and overturning a plate of éclairs.

Observing him at Pratt’s Club, Malcolm Muggeridge thinks Waugh presents a ‘quite ludicrous figure in dinner jacket, silk shirt; extraordinarily like a loquacious woman, with dinner jacket cut like a maternity gown to hide his bulging stomach. He was very genial, probably pretty plastered – all the time playing this part of a crotchety old character rather deaf, cupping his ear – “Feller’s a bit of a Socialist, I suspect.” Amusing for about a quarter of an hour. Tony [Powell] and I agreed that an essential difference between Graham [Greene] and Waugh is that, whereas Graham tends to impose an agonized silence, Waugh demands agonized attention.’

Some of his rudest remarks are delivered in such a way that few, perhaps including himself, can tell whether they are intended. ‘I spent two nights at Cap Ferrat with Mr Maugham (who has lost his fine cook) and made a great gaffe,’ he writes to Harold Acton in April 1952. ‘The first evening he asked me what someone was like and I said “A pansy with a stammer.” All the Picassos on the walls blanched.’

He delights in wrong-footing one and all. When Feliks Topolski and Hugh Burnett arrive for lunch at Combe Florey to prepare for Waugh’s appearance on Face to Face, he is at pains to point out that his house has no television set and a radio only in the servants’ quarters. He then serves them a large tureen of green-tufted strawberries. ‘Too late I saw the problem,’ recalls Burnett. ‘Put the strawberries on the plate, add the cream, take the spoon – and you were trapped with the strawberry tufts. My attempt to spear one shot it under the sideboard. That was the BBC disgraced. Topolski, seeing what had happened, did the socially unthinkable – dipped a strawberry into the cream with his fingers. “Ah, Mr Topolski,” Waugh observed helpfully, “You need a spoon.”’ When the day for the recording comes, Burnett introduces him to his interviewer, John Freeman. ‘How do you do, Mr Waugh,’ said Freeman.

‘The name is Waugh – not Wuff!’ he replied.

‘But I called you Mr Waugh.’

‘No, no, I distinctly heard you say “Wuff”.’

During the interview, Waugh confesses that his worst fault is irritability. What with? asks Freeman. ‘Absolutely everything. Inanimate objects and people, animals, anything.’

The Stravinskys and the Waughs meet up at the Ambassador Hotel on Park Avenue. Waugh is never at his best in America: he finds the natives unappealing, and upsets them with observations such as, ‘Of course the Americans are cowards. They are almost all the descendants of wretches who deserted their legitimate monarch for fear of military service.’

Stravinsky soon finds that the cutting edge in Waugh’s work is even sharper in his person. ‘Not an immediately endearing character,’ he thinks. After they have introduced themselves, Stravinsky asks Waugh whether he would care for a whisky. ‘I do not drink whisky before wine,’ he replies, his tone suggesting faint horror at Stravinsky’s ignorance.

Waugh seems to rejoice in causing all Stravinsky’s remarks, polite, lively or anodyne, to bounce back in his face. At first, Stravinsky speaks to Waugh in French, but Waugh replies that he does not speak the language. Mrs Waugh contradicts him pleasantly, but is swiftly rebuked.

The conversation stutters on. Stravinsky says he admires the Constitution of the United States. Waugh replies that he deplores ‘everything American, beginning with the Constitution’. They pause to study their menus. Stravinsky recommends the chicken; Waugh points out that it is a Friday.

‘Whether Mr Waugh was disagreeable, or only preposterously arch, I cannot say,’ Stravinsky recalls.* ‘Horace Walpole remarks somewhere that the next worst thing to disagreeableness is too-agreeableness. I would reverse the order of preference myself while conceding that on short acquaintance disagreeableness is the greater strain.’ Desperately trying to find common ground, Stravinsky attempts to relate his own recent sung Mass to the theme of Waugh’s current lecture tour. ‘All music is positively painful to me,’ replies Waugh.

The only subject on which the two of them achieve a measure of agreement concerns the burial customs of the United States. Stravinsky is impressed by Waugh’s knowledge. Waugh claims that he himself has ‘arranged to be buried at sea’, though this, it turns out, is just another of his little teases.

IGOR STRAVINSKY

IS APPALLED BY

WALT DISNEY

Burbank Studios, Los Angeles

December 1939

Igor Stravinsky is himself not the easiest of folk, but Walt Disney is not to know this when the composer drops round to his studio.

Disney is at the height of his success. Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck are the most durable and biddable stars Hollywood will ever know, and his recent Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs will gross $8 million. He has just built himself a palatial studio in Burbank, the size of a modest town, complete with its own streets, electric system and telephone exchange.

Meeting Leopold Stokowski, the conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, at a dinner party, Disney mentions an idea he has had for a two-reel version of Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, starring Mickey Mouse. Stokowski grows tremendously excited at the idea of animating great works of music. He suggests other pieces Disney might transform into colour: Bach’s Organ Toccata in D-minor, for instance. Disney sees it as orange. ‘Oh, no, I see it as purple,’ counters Stokowski.

Disney’s modest idea balloons into a full-length film, with classical music galore. Both men become over-excited: no idea seems too preposterous. Stokowski suggests a Debussy prelude, ‘Les Sons et les parfums tournent l’air du soir’, explaining that he has always craved perfume in theatres. Disney goes overboard for it. ‘You’ve got something!’ he says. ‘You could get them to name a special perfume for this – create a perfume – you could get write-ups in the papers! It’s a hot idea!’

Disney wants a sequence showing the creation of the world, full of volcanoes and dinosaurs. But what music to use? His researchers can only come up with Haydn’s Creation, but Disney thinks it doesn’t carry quite enough oomph. At this point, Stokowski alerts him to Le Sacre du printemps by Igor Stravinsky.* Disney listens to it, and is immediately gripped. He offers Stravinsky $5,000 for the rights, though Stravinsky will remember it as $10,000. According to Stravinsky, Disney hints that if permission is withheld he will use the music anyway: pre-Revolutionary Russian copyrights are no longer valid.

Stravinsky accepts; Disney steams ahead. Before long the human inhabitants of the Burbank studio find themselves working alongside animals in cages, including iguanas and baby alligators, with skilled animators studying their movements close-up. ‘It should look as though the studio has sent an expedition back to the earth six million years ago,’ enthuses Disney. He is so excited that he starts free-associating to the music: ‘Something like that last WHAHUMMPH I feel is a volcano – yet it’s on land. I get that UGHHWAHUMMPH! on land, but we can look out on the water before this and see water spouts.’ As he listens to the music, he gets so worked up that he suddenly blurts, ‘Stravinsky will say: “Jesus, I didn’t know I wrote that music!”’

Which, as it turns out, is roughly what Stravinsky does say. In December 1939, he drops into the Burbank studio for a private screening of Fantasia. The experience leaves him with the most awful memories. ‘I remember someone offering me a score, and when I said I had my own, that someone saying, “But it is all changed.” It was indeed. The instrumentation had been improved by such stunts as having the horns play their glissandi an octave higher in the Danse de la terre. The order of pieces had been shuffled, too, and the most difficult of them eliminated, though this did not save the musical performance, which was execrable.’

As Stravinsky remembers it, Disney tries to reassure him by saying, ‘Think of the number of people who will now be able to hear your music.’ To which Stravinsky replies, ‘The numbers of people who consume music … is of no interest to me. The mass adds nothing to art.’

But Disney’s memories of the meeting are quite different. Stravinsky, he maintains, made an earlier visit to the studio, saw the original sketches for the Fantasia version of Le Sacre and declared how excited he was. Later, having seen the finished product, Stravinsky emerged from the projection room ‘visibly moved’. Disney remembers the composer saying that prehistoric life was what he always had in mind when he wrote it. But Stravinsky disagrees. ‘That I could have expressed approbation over the treatment of my own music seems to me highly improbable – though, of course, I should hope I was polite.’

Either way, he is much less polite twenty years later, when he and Disney clash in the pages of the New York Times. He dislikes what was done to his music, he writes, and furthermore, ‘I will say nothing about the visual complement as I do not wish to criticise unresisting imbecility.’

Whose memory are we to trust? There may be a temptation to favour the highbrow over the lowbrow, the intellectual over the populist; but self-delusion rains on all, high and low. Many artists who took money from Hollywood felt able to absolve themselves by seeking a divorce from the finished product. For them, the prevailing myth of the philistine Hollywood producer offered a welcome escape hatch.

By and large, the evidence favours Disney. Less than a year after their supposed contretemps, Stravinsky cheerfully sells Disney two more options – one on the musical folk tale Renard, the other on The Firebird.* And his artistic halo always has a certain rubbery quality about it: he composes some hunting music for Orson Welles’s Jane Eyre, and after contractual negotiations break down, uses the very same piece for a commission from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, transforming it into an ode to the memory of the wife of Serge Koussevitzky. On another occasion, he lifts the incidental music he has been commissioned to write for a film about the Nazi occupation of Norway, Commandos Strike at Dawn, straight from a collection of Norwegian folk tunes his wife has stumbled upon in a second-hand bookstore in Los Angeles. When this deal falls through, he further rejigs it into a piece for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, solemnly retitling it ‘Four Norwegian Moods’.

WALT DISNEY

RESISTS

P.L. TRAVERS

Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, Los Angeles

August 27th 1964

It is all smiles as Walt Disney and his most recent collaborator, P.L. Travers, pose with Julie Andrews at the world premiere of Mary Poppins. This, he tells reporters, is the movie he has been dreaming of making ever since 1944, when he first heard his wife and children laughing at a book and asked them what it was. At his side, Travers, aged sixty-five, appears equally thrilled. ‘It’s a splendid film and very well cast!’ she enthuses.

The premiere is a lavish affair. A miniature train rolls down Hollywood Boulevard with Mickey Mouse, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Peter Pan, Peter Rabbit, the Three Little Pigs, the Big Bad Wolf, Pluto, a skunk and four dancing penguins on board. At the cinema, the Disneyland staff are dressed as English bobbies; at the party afterwards, grinning chimney-sweeps frolic to music from a band of Pearly Kings and Queens.

The next day, Travers is over the moon, wiring her congratulations to ‘Dear Walt’. The film is, she says, ‘a splendid spectacle … true to the spirit of Mary Poppins’. Disney’s response is a little more guarded. He is happy to have her reactions, he says, and appreciates her taking the time, but what a pity that ‘the hectic activities before, during and after the premiere’ prevented them from seeing more of each other.

Travers writes back, thanking Disney for thanking her for thanking him. The film is, she says, ‘splendid, gay, generous and wonderfully pretty’ – even if, for her, the real Mary Poppins remains within the covers of her books. On her copy, she adds a note saying that it is a letter ‘with much between the lines’. The same month, she complains to her London publisher that the film is ‘simply sad’.

Those smiles at the premiere are, in fact, the first and the last they will ever exchange. Pamela Travers is a long-time devotee of Gurdjieff, Krishnamurti, Yeats and Blake. For her, the Mary Poppins books were never just children’s stories, but intensely personal reflections of her Alphabetti Spaghetti blend of philosophy, mysticism, theosophy, Zen Buddhism, duality, and the oneness of everything. In the last year of her life, she will reveal to an interviewer that Mary Poppins is related to the mother of God. Disney’s own conception of the finger-clicking nanny is rather more straightforward.

Nothing about the film of Mary Poppins has been easy. The contract alone took sixteen years to negotiate: Travers finally accepts 5 per cent of gross profits, with a guarantee of $100,000. But this is to prove inadequate compensation: she soon begins to complain that Disney is ‘without subtlety and emasculates any character he touches, replacing truth with false sentimentality’.

Walt Disney’s attitude to Travers is one of damage limitation. He wants to keep her on board, but positioned as far as possible from the driver’s seat. This does not stop Travers making frequent lunges for the steering wheel, generally with a view to forcing the vehicle into reverse. She complains about everybody and everything, even stretching to the type of measuring tape Mary Poppins would use.*

She objects to all the Americanisms that seem to be creeping in – ‘outing’, ‘freshen up’, ‘on schedule’, ‘Let’s go fly a kite’ – and considers the servants much too common and vulgar. Furthermore, the Banks home is much too grand, and any suggestion of a romance between Mary Poppins and the cockney chimneysweep Bert is utterly distasteful. Finally, she objects to Mrs Banks being portrayed as a suffragette, and considers the Christian name they impose on her – Cynthia – ‘unlucky, cold and sexless’, her own preference being Winifred.

Travers even believes her responsibilities extend to the casting.* The day after Julie Andrews gives birth, she phones her in hospital. ‘P.L. Travers here. Speak to me. I want to hear your voice.’ When they finally meet, her first remark to the actress is, ‘Well, you’ve got the nose for it.’

Mary Poppins is a worldwide success. Costing $5.2 million to make, it grosses $50 million. But the more the money rolls in, the more Travers’ attitude to the film and its creator sours. She tells Ladies’ Home Journal that she hated parts of the film, like the animated horse and pig, and disapproved of Mary Poppins kicking up her gown and showing her underwear, and disliked the billboards saying ‘Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins’ when they should have said ‘P.L. Travers’ Mary Poppins’.

She writes to a friend that Disney wishes her dead, and is furious with her for not obliging. ‘After all, until now, all his authors have been dead and out of copyright.’ But there is always the promise of a sequel, and yet more money. It is only when Disney dies in December 1966† that her objections become more concentrated and vocal. In 1967, she says that the film was ‘an emotional shock, which left me deeply disturbed’, and in 1968 that she ‘couldn’t bear’ it – ‘all that smiling’. In 1972, she declares in a lecture that ‘When I was doing the film with George Disney – that is his name, isn’t it – George? – he kept insisting on a love affair between Mary Poppins and Bert. I had a terrible time with him.’

Her invitation to the world premiere is, it later emerges, not achieved without a struggle. Failing to receive an invitation, she instructs her lawyer, agent and publisher to demand one on her behalf. When it is still not forthcoming, she sends a telegram to Disney himself, informing him she is in the States, and plans on attending the premiere: she is sure somebody will find a seat for her, and will he let her know the details? Her attendance is, she adds, essential ‘for the dignity of the books’.

Disney writes back saying that he has always been counting on her presence at the London premiere, but is now delighted to know she will also be able to come to the premiere in Los Angeles. And yes, they will happily hold a seat for her.

P.L. TRAVERS

WATCHES OVER

GEORGE IVANOVICH GURDJIEFF

The American Hospital of Paris, Neuilly-sur-Seine

October 30th 1949

Any meeting between the living and the dead is inevitably one-sided. Do they know something we don’t know?

On October 30th 1949, P.L. Travers sits all night in a private room on the first floor of the American Hospital of Paris, gazing lovingly at the corpse of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff.

Pamela first encountered Gurdjieff thirteen years ago, in 1936, at his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, near Fontainebleau. After spending much of her life pursuing poets and mystics, she found in Gurdjieff what she had long been looking for, and was particularly drawn to his unusual emphasis on finding truth through dance. Back in London, she was to teach these Gurdjieffian dances before progressing to teaching the teachers; she spread his beliefs for the rest of her life.

Gurdjieff was a guru with an opaque past. Half Armenian, half Greek, he cultivated obscurity about many things, not least his age.* He tried his hand at many trades, dealing, in different places and at different times, in a range of products including carpets, antiques, oil, fish, caviar, false eyelashes, sparrows and corsets.

But around 1912, he found his calling as a guru, his core belief being that ‘modern man lives in sleep, in sleep he is born and in sleep he dies’. Only by subscribing to Gurdjieff’s special training could modern man snap out of it, rise to a higher level of consciousness, and find God, or, as Gurdjieff preferred to call Him, ‘Our Almighty Omni-Loving Common Father Uni-Being Creator Endless’.

Among his many other beliefs was that the moon lives off the energy of dead human beings, known as Askokin, and controls all man’s actions. To guard against rebellion, the higher powers have implanted an organ at the base of man’s spine called the Kundabuffer, which stops him becoming too intelligent.* Only those who follow Gurdjieff’s path can break away from their fate as food for the moon, and thus attain immortality.

P.L. Travers’ most famous creation, the flying nanny Mary Poppins, might be seen as Gurdjieff in a long dress, shorn of his handlebar moustache and propelled by an umbrella: in some of the stories, Poppins guides her charges to the secrets of the universe, with the planets all indulging in a great cosmic dance. In the chapter ‘The New One’ in Mary Poppins Comes Back, Mr and Mrs Banks give birth to a new baby, Annabel, who, it emerges, is formed from the sea, sky, stars and sun. Mary Poppins is, to all intents and purposes, one of the enlightened, aware of worlds beyond.

As Pamela Travers sits beside the corpse of Gurdjieff, she believes that the real Gurdjieff is somewhere else, somewhere on another plain, reunited with the being he used to call the Most Most [sic] Holy Sun Absolute. Alive, he was the most earthy of men, enjoying huge three-course meals, washed down with Armagnac, while his followers made do with bowls of thin soup. Some non-believers found his personal habits unseemly. In his palatial flat at his institute in Paris, he often didn’t bother to visit the lavatory, preferring to defecate willy-nilly. ‘There were times when I would have to use a ladder to clean the walls,’ recalls one of the residents. He demanded unquestioning obedience from his wealthy followers, and enjoyed humiliating them; it was almost as though he relished the sight of grown men in tears. He was a stranger to celibacy, and loved to boast of all the babies he had fathered, peppering his pidgin English with the word ‘fuck’. But for his devotees this only added to his air of other-worldliness: surely a guru so un-gurulike could not possibly be a fraud?

The Second World War separated the guru from his protégée. Stuck in Paris, Gurdjieff refused to let the Nazi occupation hinder his lifestyle, feasting on delicacies from local suppliers attained with promises – bogus, as it turned out – of massive wealth owed to him from a Texan oilfield.

The moment the war was over, Pamela travelled to Paris on one of the first trains. She sat with Gurdjieff’s other disciples and imbibed his latest thoughts and aphorisms such as ‘Mathematic is useless. You cannot learn laws of world creation and world existence by mathematic,’ and ‘Useless study Freud or Jung. This only masturbation.’ He advised Pamela and his other followers to have an enema every day, then donned a tasselled magenta fez to play his accordion in a minor key. ‘This is temple music,’ he assured them. ‘Very ancient.’

Pamela saw Gurdjieff in Paris for one last time a little under a month before he died. She brought her adopted son, Camillus, who told Gurdjieff that he had no father. ‘I will be your father,’ said Gurdjieff. On October 25th 1949, Gurdjieff was taken to the American Hospital, carried into the ambulance in his bright pyjamas, smoking a Gauloise Bleue and exclaiming merrily, ‘Au revoir, tout le monde!’