Godless in Eden

FAY WELDON

Godless in Eden

A book of essays

Contents

Cover

Title Page

The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live As Women

A Royal Progress

This Way Madness Lies

The Changing Face of Government

Brushing Up Against the Famous

Growing Up and Moving On

Bibliographical Note

About the Author

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

The Way We Live Now

A new Britain indeed: a Third Way, a great sea change in how we see ourselves. Fifty-eight million people, in fact, in profound culture shock. To determine how we live now, first determine how we lived then.

Pity a Poor Government

Behind the Rural Myth

Mothers, Who Needs ’Em?

The Feminisation of Politics

What This Country Needs Is:

Take the Toys from the Boys

From The Scotsman Millennium Lecture, delivered at the Edinburgh Book Festival, summer, 1998.

Pity a Poor Government

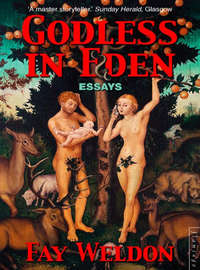

Adam and Eve and Tony Blair. The beginning and the end: or at any rate as far as we’ve got at the close of the fourth millennium since the Garden of Eden, when we all began, and the second since Jesus, when we started counting.

But these things may be circular; the end may yet turn into a new beginning. We now have a New Adam and a New Eve (if the same old Cain and Abel kids). God is no longer seen to exist, to bar the door with flaming sword. The bearded patriarch has been replaced by Mother-Goddess Nature. The happy couple walk again in paradise. The Garden, mind you, is pretty battered these days, it lacks its ozone layer, it is buffeted by the storms of global warming and so on. But at least the serpents of hunger, poverty and ignorance have slid off into the undergrowth, driven out over the centuries by marauding parties of the Great and Good.

Pity any poor government as it tries to keep up with unprecedented social change and the collapse of the old ways of living, dealing as it has to with an electorate still immersed in the old myths of what we are and how we hope to be, obliged to piddle about with Ministries for Women when what we need is a Ministry for Human Happiness. Changes in the female condition, however welcome, have had their effect on men and children too. Takes two to make the next one – and our evolution as a species, over too many millennia to count, suggests to us most forcibly that we are all inextricably interlinked, and if we try too hard to escape our conditioning, fly too obstinately in the face of our human and gender nature, we will be very miserable indeed. But what are we, if we don’t try? Let government admit a paradox, and help us all pursue our happiness, not just some of us our rights.

The young couple, the New Adam, the New Eve – he beginning to feel the effect of the lack of a rib, she taking over the gardening: their life expectancy now in the late seventies (him) and the early eighties (her) – have in returning to the Garden been returned to innocence: they walk about its glories in a daze. Innocence may not be enough if they are to remain, this time round, in the state of grace we want for them. Let them have some information.

I can’t cover a thousand years of gender politics but I can just about manage the last hundred years. The great advantage of being no longer young is that what to many people is dead history to me is living history, if I add in my mother, that is, who is alive and well and thinking and ninety-one. Since she was there for the decades I was not, between us we can set ourselves up as experts on the century.

I spent my early years in New Zealand, where the education was based upon ‘the Scottish system’. By which is meant that the young are not trusted with independent judgement, and no-one asks ‘what are your feelings about this?’ because your feelings are irrelevant. We learned what others older and wiser than ourselves had to say. We quoted authority if we wanted to prove a point. (In those pre-television days it was possible to take authority seriously. Put Locke, Berkeley and Hume on a late night chat show and you’d soon lose respect for them.) In 1946, my family, mother, grandmother, sister and myself, took the first boat ‘home’ after the war, and I went to a girls’ grammar school in London which expected its pupils to join the great and the good and work for the betterment of mankind. Many of us did. And later I went to the University of St Andrews, where I developed the art of rhetoric. Thus: you make your case, overstating it dramatically. Your opponent does the same. In response you reduce your argument a little: so does he. Thus a consensus, or at any rate a moderation of extreme views can be reached. Except of course if you’re arguing with someone who doesn’t understand the rules of engagement, and they usually don’t down South, you’re in trouble. Others conclude you’re hopelessly argumentative, given to rash overstatement, and would be well advised to stick to writing fiction, which as everyone knows, and as my mother pointed out to me long ago, is all lies and exaggeration anyway. You make a statement: they leave the room.

It was my Professor in moral philosophy at St Andrews who, when obliged by new university directives to accept females into his class – there were three of us – declined to mark our essays or acknowledge our presence, other than from time to time to remark, with a toss of the bald head, that females were not capable of moral decision or rational judgement. The only conclusion we could come to was that we were not female. That was in the early fifties, of course, and in those days to be denied ‘moral decision’ and ‘rational judgement’ was meant as an insult. Today a young person might well interpret the remark as a compliment. Feeling takes such precedence over morality and judgement, emotional response is declared to remain so much the woman’s prerogative, that it is the young men in the class who would be the ones to feel inadequate, and long to be women, just as we then longed to be men, to be allowed out after our begrudged education into the great wide world of adventure, excitement, earning, and freedom. Not into the domesticity which seemed to be our fate, both as natural born women and because it was so difficult for a woman to earn anything other than pin money. And today’s young man might well find himself the solitary male in a Gender Studies Class expected to stay quiet when the female lecturer tells the class that all men are potential rapists.

When my mother observes, as she did the other day, that when she was a girl only working women wore blouses and skirts, and that a lady would be horrified to be seen in anything but a dress, and equally horrified if a working woman turned up wearing something in one piece, you realise how profoundly and invisibly and silently things can change, and how easy it is to forget the kind of society we once were, as we try to make sense of the one we have now. You understand why the office liked you always to wear a suit to work, and wearing a dress made them, and you, feel uneasy, and why the BBC got so upset in the sixties if you wore trousers to a meeting.

Why, I asked my mother, if there are only six million more people in this country than there were in 1950, and this is only a ten percent increase in the total population, is it so difficult to get along Oxford Street for the crowds? And why is it that the simple purchase of a pair of shoes these days takes so long and requires a lengthy session with a crashing computer? To which she replied ‘Because once upon a time everyone used to stay home, you silly girl. They were poor. Their one pair of shoes was wet and they couldn’t go out until they were dry. They didn’t even aim to have two pairs. No-one ate in restaurants, bread and cheese was the staple diet and you got them from the corner shop and paid cash, and if you didn’t have cash you went without. And that was in the fifties – things were twice as quiet when I was a child.’

My mother’s parents, at the turn of the century, ran to a cook and a maid who lived in, and had one half-day off a week. They were certainly not out littering the streets, buying shoes or overcrowding public transport.

In the East End of London, before bombs razed so much of it during two world wars, and the planners got busy with their theories, nearly everyone lived within walking distance of work. And how they worked! In 1901, we had 75,000 boys under fourteen in the factory workforce, and nearly as many girls. The school leaving age was thirteen and child labour was common in spite of it, and it was normal for women to work before they had families. But not after, if they could help it. In the civil service and in teaching, what was called the Marriage Bar meant a woman had to give up her employment – in blouse and skirt, of course – when she got married. Otherwise who would run the nation’s homes? A whole lot of women just got married secretly, of course, and failed to tell their employers.

Halfway through the century, by the time I was being taught by Professor Knox, though the Marriage Bar was gone, it was certainly assumed that an educated girl chose between a personal life and a career. Now it is assumed that somehow, what with the washing machine, the microwave, the vacuum cleaner, and this strange thing called childcare, which is another woman looking after her child for less than the mother earns, she will be able to manage both. And she can, just about, and often wants to, and often has to. And it can be hard. We have paid a heavy price for our emancipation, but more of that later.

And when I say people worked hard then, believe me they work harder now. My mother views with horror today’s average working week of forty-eight hours – and middle management works sometimes sixty or seventy, plus the journey to and from work – saying that even before World War II the attempt was to get the figure down to thirty-five. And that when in the late fifties she worked as a porter on London’s Underground – the winters were cold and staff were issued with heavy greatcoats, for which she was thankful – even then the staff worked only a forty-hour week. What happened? And as for part-time work – the kind women with children so often do – this is usually an employer’s definition and doesn’t necessarily mean shorter hours, just that the employee works without holiday or sick pay and has no statutory rights. I know ‘part-time’ college lecturers who work longer hours than the full-time staff, but for less money, and are still grateful. It’s that or nothing.

Of course things have improved. They must have. Our life expectancy is greatly increased. My mother’s life expectancy when she was born was fifty-two years. My father’s was forty-seven. A girl child born today can expect to get to eighty-one, a boy child seventy-six. The gender gap in this respect has neither closed nor narrowed. Women are born to live longer on average than men, in the human species as in most others. At the beginning of the century one hundred and sixty males per million did away with themselves: the figure for women was forty-eight. Now it’s down to one hundred and four males and thirty females. Woman is not so given to despair, it seems, as Man, and though the totals drop, thank God, they stay pretty much in the same gender proportion, three times fewer women than men. We both mostly do away with ourselves when we’re old and lonely. We were not bred for loneliness, though the contemporary world forces too many of us into it. The government plans to build 4.4 million new housing units, to house those expected to live alone in the next decade, and that figure rises steadily. As Patricia Morgan at the Institute of Economic Affairs points out, in a booklet on the fragmentation of the family, men’s disengagement from families is of immense and fundamental significance for public order and economic productivity. This is something which is only just beginning to be acknowledged – as we blithely head for a situation in which, by the year 2016, fifty-four percent of men between thirty and thirty-four will be on their own.

So pity the poor male as well as pity the poor government. One’s anxiety on their behalf has less to do with girls doing so much better at school exams than boys, which they so famously do, but with changes in society which make it difficult for us all to do what comes naturally. That is, to fall in love, marry, and live happily ever after in domestic tranquillity, even though we prefer now to do this serially. The late twentieth century is wreaking havoc with our aspirations to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. May we please have our Ministry for Human Happiness? Or if the government really wants to be useful, and preserve the marriage tie and so forth, thus saving itself large chunks of the £800 thousand million annual benefit budget spent mopping up the mayhem left by divorce, it could institute official stigma-free dating agencies, and set about arranging sensible marriages. The self-help system seems to be breaking down. And the steadiest citizen is the married citizen, and the one most pleasing to the State, tied down and sobered by kids and mortgage obligations.

My mother and I, of course, both have to thank the twentieth century for our continued existence. Let me rephrase that. Were it not for medical advances we would neither have seen so much of it. I would have been dead twice, once for lack of antibiotics, once for lack of plausible surgery. So would she. I would have three surviving children, not four. One would not have survived birth. Mind you, were it not for the advent of contraception, I might have ended up having ten. When Marie Stopes worked in London’s East End at the beginning of the century there were women around who had survived twenty children or more: but the normal fate of the married woman was to die young from repeated childbirth, contraception being both illegal and seen as immoral. For every child she carried, Stopes estimated, a woman’s chance of dying in childbirth increased by fifty percent. If the marriage rate then was a mere one in three I am not surprised. Marriage might have meant status and children, and even, in George Bernard Shaw’s phrase, been a meal ticket for life for women, but was still too often a death sentence, especially amongst the poor. Things are better now: infant and maternal mortality is way, way down to almost nothing – from over one in ten in 1900 to less that four per thousand now – but with improved health, prosperity, the advent of contraception and women’s control of her own fertility, comes a new set of problems. So it goes.

My mother at the age of five, when first required to go to the little Montessori school around the corner, set up such a wail that my grandfather, a novelist, came down the stairs in his silk dressing gown, waving his ivory cigarette holder and said what can be the matter with little Margaret? To which the reply came she doesn’t want to go to school. ‘Do you want to go to school, Margaret?’ he asked, and my mother replied no, though she knew even then, she told me, that it was a life decision and she’d made the wrong one. My grandfather said, ‘Don’t send her then,’ and went upstairs again, and they didn’t. She stayed at home and read books and by the age of twenty was writing novels with her father.

Education for my mother and myself was for its own sake. It was not training, as it is now, for the adult world of work. The motive behind the education acts of the nineteenth century, which made school compulsory, was not by any means purely philanthropic: rather it was to accustom the children of an agrarian society to industrial ways, so by the time they left school they’d have got into the habit of turning up at the factory even when it was raining and cold, they felt poorly, or their shoes were wet and it was Monday morning. Monday was always a bad day for turning up at work. And the truant officers of the new compulsory schools, the morning and afternoon register, and the sick note required to prove illness, did indeed quickly train the new generation to daily work in the factories, bother reading and writing.

Likewise today we train our children, through longer and longer years, from their first day at the creche or the playgroup, to their last day at college, to turn up, to be there, to answer the register, to compete in exams as later they will for jobs, computer fodder in the new technological society, as once they were factory fodder. It is the effective use of computers we care about, just as once we cared about getting a return on our new industrial machinery: alas, machinery works day and night and doesn’t tire, as humans will.

Our children, training for their future, in which there will always be too many workers and not too few, and so a permanent level of anxiety to keep everyone striving, end up living in an examination culture: they are tested and tried on entry to playgroup, they have SATS at 7, 11 and 14, GCSE’s, A-levels, secret personality records and all. What price the old hated eleven-plus now? That exam was as nothing. Who wanted to go to the grammar school, anyway, it separated you out from your friends. Passing it was the problem, not failing it.

Life for the child mid-century was comparative heaven. No over-trained teachers, no national curriculum, and very little truancy, why should there be? School was where you went to meet your friends: education was a by-product: they were small, quiet places. Holidays were longer, the years spent in schools were fewer, educational standards were higher. And even so, my mother didn’t want to go.

Mid-century I was lucky. I got the best of perhaps any education system the world has had to offer. Under Mr Attlee, the last of the great disruptive wars behind us, having got off the boat from New Zealand in 1946, a small family of female refugees, without possessions, into the confusion and turmoil of that grey, pock-marked, war-torn city, London, with its rationed food and its icy cold, all of us living in one room with only a glimmer of gas to light and warm it, the State plied me with orange juice and cod-liver oil. It not just sent me to a ‘maintained’ grammar school, but paid for me to go, bought me my clothes, gave me free meals, sent me to university when I was seventeen to study Economics and Psychology and become part of the future. What you have in me is what the Attlee government made of me. I got a student’s grant of £167 a year plus tuition, paid for me by the London County Council, which seemed to me to be unbelievable riches, and which indeed, if you worked in the coffee shop in the evenings, was enough to keep you and indeed even buy you a second pair of shoes. And in the summers you hitched South: the world after the war seemed a safe and gentle place: it had got its violence out of its system. Now the violence is in the tent, not out of it. Forget hitch-hiking, we feel we can’t even let our children walk to school alone in safety. Lacking an outside enemy, the attack from Mars or a meteor from outer space, I fear it may well stay like that.

Conflict at the turn of the century, and indeed up to the middle of it, was solved by war, male antlers locking, carnage on the battlefront. War, at least in the mind, if not so much of course by those compelled to participate in it, was to do with courage, chivalry, sacrifice, nobility, prowess, endurance, patriotism. Traditional male virtues, now much despised. These days in our female way we negotiate, cajole, tempt, explain, forgive, apologise, touchy-feel our way to world peace, while small savage macho wars, mini-skirmishes, little spasms of ethnic cleansing, break out here and there.

The International Monetary Fund bales out the Japanese, the Russians: we look after our economic relatives: old enmities are forgotten. And of course this is preferable to war. But without our external enemies we turn inwards: societies and individuals go on self-destruct benders. Crime, drugs, the break-up of the family, the abandonment of children, the loneliness of the individual, the alienation of the young, the pause button so often on the sadistic act of violence on the TV: are all features of today’s peaceful, caring society. And perhaps they are all inevitable. Jung would talk about a process called enantiodromia, when all the currents of belief that have been running one way suddenly turn and run the other, in the same way a river zig-zags rather than flows steadily down a hill, reversing its direction when too much pressure mounts. The more smoothly the confining, caring, peaceful society seeks to conduct itself, the more likely some of its members are furiously to run in the wrong direction, lost to all responsibility and decent feeling, vandalising and tearing everything to bits as they go. It wasn’t what they wanted: it was never what they wanted. What they wanted – because the source of the trouble is mostly male – was to be allowed to be men in a society which so disapproves of maleness.

Signs of maleness – interpreted as aggression, selfishness, sexual addiction – are treated by the therapists and counsellors, who take the place of the old patriarchal priesthood: they are the new pardoners, forgiving our sins for the payment of money, releasing us from personal guilt. Women are confirmed in their traditional self-absorption: seek the authenticity of your own feelings, they cry. Go it alone! You know you can! Assert yourself, your right to dignity, to personal fulfilment! Never settle for second best.

And of course they are right, except, in the face of such stirring advice, and because in the new Garden of Eden men and women can, when once men and women couldn’t, marriages and relationships crumble and collapse. According to a recent poll in the women’s magazine, Bella, more than fifty percent of young women think a man isn’t necessary in the rearing of a child, and seventy-five percent think that if she wants to conceive a child when she doesn’t have a partner it’s better to go to a sperm bank than have a one-night stand. Seventy-five percent. Back at the turn of the century sex was something women put up with in return for a wedding ring and all that went with it, not something they were meant to enjoy. So what changes, in spite of what a lot of other women’s magazines have had to say on the joys of sex in between?

I am not lamenting the past. We live a whole lot longer than we did; that must prove something. Though quite how we keep our Zimmer frames polished I don’t know, as both the birth rate and the marriage rate falls. Many of today’s young will grow up to live alone and not with families: friends and colleagues will have to look after us, the New Adam and the New Eve, when we grow old, or break a leg, or are made redundant, or go mad or whatever. What price independence and self-assertion then? The State is increasingly determined not to look after us, and if our families are fragmented, how can we look after ourselves?

We are all so much weaker than we believe, than the myth of the strong man, even the new one of the strong woman, allows us to be. We need all the support we can have. And as for our financial arrangements! Good Lord, you can’t trust them. Banks collapse, as do whole national economies, nothing is secure, not even your Insurance Company, not even your PEPs. It’s understandable, I take the view. I belong to the robbed generation. I started work at the Foreign Office in 1953 – earning £6 a week as a temporary assistant clerk; I worked for some fifteen years, here or there, before I became self-employed, on PAYE, paying out a vast proportion of my weekly pay packet, or so it seemed to me at the time, for my Social Security stamp. Now I get the old age pension they promised me and it’s 44p a week. Robbed! And what about all those who having no savings, no longer able to earn, endure the indignity of having to ask for income support? Their mistake, having been told they were providing well enough for their futures, was to believe what they were told. Successive governments simply did a Maxwell with the pension funds, and didn’t even have the grace to acknowledge it, let alone jump overboard.