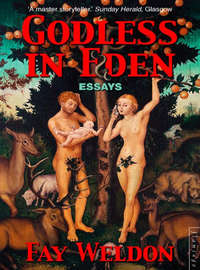

Godless in Eden

The State is increasingly cavalier with its dependants. I know of a man with two artificial legs who because he can walk across a room – just – doesn’t get incapacity benefit any more. It was withdrawn in the last so-called fraud purge, a few months back, when everyone on incapacity benefit was called to a fifteen minute interview with a non-specialist doctor and the lists cut across the board by some ten percent. Just like that. Sure you can appeal but if you do you lose a whole set of other benefits while you wait, and then how do you eat? Is so much misery worth so small a saving to the State?

The matter of the burden to the tax-payer of the benefit bill preoccupies government to an absurd degree. States with any spare money tend to go to war, and then we pay for that. Look at the books. Total government receipts, 1998, £309 thousand million. Total government expenditure £320 thousand million. We borrowed £11 thousand million from ourselves to balance the books. (You can get all these figures from the back of your Economist Desk Diary. Take off a few noughts from the sums and it’s no different from adding up your own cheque stubs.) Out of that £320 thousand million, Social Security costs us a mere £79 thousand million. I suspect one way or another we’d go on paying the same taxes even if we stopped spending on our poor relations altogether, and allowed the unemployed, the undertrained, the sick, the weak and the inadequate, the helpless in our highly complex society, to starve to death on the streets. And what kind of family would we be if we did this? How would we live with ourselves?

One of the phenomena of the late twentieth century has been the growth of political correctness, of self-censorship, a quite false belief that we have reached the pinnacle of proper understanding, and a fear of saying what we think in case we offend our friends. It becomes important that we all think the same: and indeed, the rise of emotional correctness requires that we all feel the same. We allow ourselves as little freedom of thought as if we were Marxist-Leninists, even though there’s no-one around to put us in prison. Sexism, it is held, contrary to the evidence of the eyes and the ears, can flow only one way, from man to woman, just as racism can flow only from white to black. That both are now two-way streets we find difficult to accept.

Sometimes it seems to me that with the fall of the Berlin wall freedom fled East and control fled West. Jung’s enantiodromia at it again. Turn, and run the other way down the tramlines. In Russia now see the worst excesses of venture capitalism and personal freedom, wealth which breaks all sumptuary laws brushing up against extreme poverty, an abundance of crime, coercion and murder, and the flight of altruism. While here in the West we have the creeping Sovietisation of our culture: the advent of a dirigiste government: we are controlled, surveyed, looked after, nannied, bureaucratised. We live amongst secrets: our news is manipulated. We all know it, but don’t much care. We have direction of labour. What else is Welfare to Work? If you can’t get your own job, take the one we give you. On which I notice the government spent £200 million last year, and did get a few actually back to work, but for the most part only temporarily. And for every person who got a job there must be another one put out of work – how can it be otherwise, when we still have a seven and a half percent unemployment rate. Wouldn’t it have been cheaper to just go on paying out benefits and saved everyone a lot of aggravation, humiliation, cold calling and letter writing? Or better still created work for people to do? But that would interfere with the Bank of England’s belief that there is a ‘natural’ rate of unemployment – defined by them as the lowest rate compatible with stable inflation. They like it pretty much as is – not too high to cause rioting in the streets. High enough to keep workers in a state of anxiety and doing what they’re told. In the light of such official or semi-official policy, Welfare to Work projects look oddly like window dressing. Or, less cynically, the thinking goes like this. True, we need a calculable pool of people standing around doing nothing, to cool an overheating economy – but it’s just so irritating when they stand around. Let them at least be seen to be working at not-working, which is what the new Jobseekers’ Allowance amounts to.

Since the unemployed appear to be burnt offerings to the stability of our economy, martyrs in the cause of the low inflation and the high interest rates which keep the City happy, I think they should be treated with vast respect and allowed to live in peace, dignity and the utmost comfort.

As for the employed, the conviction seems to be that if only everyone works longer and harder, women alongside men, we’ll all be better off. But better off how? Where’s our Five-Year Plan? What exactly is all this effort for? And has no-one noticed that in spite of having the longest working hours in Europe we have the lowest productivity? Of course we do. We’re exhausted.

And we’re certainly no longer working for the children: they poor things are Kibbutzised, taken away from their parents and returned to them only at nights, so the parents are free to work to make the desert bloom. Which is all very well, but there’s no desert outside the window when the children look, and no drastic emergency, just a whole lot of new cars and new roads and new buildings and shoe shops and the Millennium dome.

We live now under Ergonarchy. By Ergonarchy I mean rule by the work ethic. Forget Patriarchy, rule by the father, it’s Ergonarchy which is woman’s current enemy, now that she’s joined the workforce. While she was doing battle with Patriarchy, Ergonarchy sneaked in under cover of darkness and ambushed her. Ergonarchy insists women work but goes on paying them less. This isn’t because Ergonarchy is male – Ergonarchy’s an automated accountant, neuter and blind and unable to tell one gender from another – but simply because women, if they have children, can’t give their bosses the time and attention they require, and so end up contributing less and getting paid less. Ergonarchy’s best friend being Market Forces.

And thus it will continue until society gets Ergonarchy under control, by the drastic measure of accepting that men are fathers too, and inviting them on board as equal parents. On the day when the problem of the working father is talked about as often as is the problem of the working mother, we will be getting somewhere. All children have two parents, though you’d never think it.

I am not suggesting, you must understand, that mothers should stay home and look after the children. I don’t want them forced back into the kitchen, heaven forfend, for this is just another kind of loneliness, albeit temporary. I want my Ministry for Human Happiness to ensure mothers are out there doing half as many hours for twice as much money.

Evidence of continuing male prejudice against women comes from the fact that the female wage is persistently lower than the male wage: though in Britain the gap is smaller than in the rest of Europe. But it is not on the whole the villainy and prejudice of men that leads to this undoubted inequity: it is the fact that the majority of women end up with children, and choose to give them more attention than they do their jobs. Even when partnered, many back off when the time comes for promotion, deciding that time for a personal and emotional life is more valuable than earning more money. The part-time nurse does not take the job as full-time ward sister, the TV researcher turns down the job as producer, because if they move up the ladder, when would they ever get to see the kids. The piece-worker in the home stitches shoes at 50p a pair because she has an ill child and is open to exploitation – not because she is a woman but because she is human being with a baby, and has no other options open to her. The earning capacity of the lone father (a fast growing group), falls as drastically as does that of the mother, when loneness strikes. While every working woman who has a small child pays another woman less than her own market value to look after the child – and she must, or she can’t afford the job – how can equality of wages be achieved? What meaning does ‘equal opportunities’ have, other than for the childless woman? If the statistics which told us about our comparative earnings made a distinction not just between men and women, but between men, childed women and unchilded women, we would begin to get somewhere – but they don’t. All women come under one heading. The fact that we do so well in the European league table suggests to me not that we’re moving towards gender equality, but that we have too many tired and overworked women with children amongst us.

We are barking up a dangerous and creaky old-fashioned seventies tree, when we go on struggling for equal wages, with the ardent encouragement of the government, when we would be better occupied turning men into resident and supporting fathers, instead of dismissing them from the case and saying, ‘Which way to the sperm bank?’ or, ‘How dare you treat me like this,’ or, ‘Oh I can manage alone and anyway there’s always the CSA, not to mention benefits. What makes you think I need a man?’

These days we tend to call our employment our ‘career’ and not our ‘job’. A career is something in which you compete with your colleagues for promotion, must be sharper and faster and harder working than they are, and put in longer hours. Thus we are divided and ruled, by big bosses so well hidden in the bureaucratic undergrowth it is next to impossible to fight them, let alone detect them.

There is no-one around these days to protect the employee – except now perhaps legislation out of Europe, for which God, male or female, be thanked. In the big State organisations – health, education, local government – accountants rule. Their duty is to cut costs and save the tax-payer’s money. So for the employee it’s all downgrading and re-writing of contracts, and here’s your redundancy money if you argue. The big companies look after the interests of share-holders first, customers second and employees last if at all. And the individual employer profits out of your skill and labour and always has but at least he’s around to meet your eye.

This Garden of Eden of ours is still open to Marxist interpretation, even in this the Age of Therapy.

Adam and Eve and pinch me

Went down to the river to bathe,

Adam and Eve were drowned,

And who do you think was saved?

Pinch Me, says the innocent child, and everyone runs round the playground screaming. Well, that’s how it used to be. The New Adam and the New Eve know better than to drown in the river, and the children’s playgrounds no longer ring with traditional rhymes: playtimes get shorter, and holidays too, as the schools adjust their working hours to the offices and not the other way round. The New Adam and the New Eve, victim of the Ergonarchy, have no time left to go down to the river and stand and stare, and contemplate the marvel of creation.

The New Adam, I say, and the New Eve. We are not what we were. Our instincts may lead us in the same old direction: our rational understanding leads us in another. Four things happened in the middle of the twentieth century to change our gender relationships profoundly and for ever, so that our nature and our nurture are no longer at peace. We’re just not used to it. The first two events are to do with medicine, the third to do with that powerful revolutionary idea, feminism, and the fourth to do with our new technological society. These are converging dynamics: you can’t have one without the other, like love and marriage back in the fifties. That was when we managed a marriage rate of nearly ninety percent, and the majority of those marriages were permanent. It can be managed.

The first event was female access to contraception. At the beginning of the century, as I say, contraception was illegal: it offended the Church – the flow of souls to God had to be maintained: it offended the State – whose need was for labour in time of peace and cannon-fodder in time of war. The convenience of authority sheltered, as ever, under the cloak of morality. From the sixties on, with the advent of the pill, gruesome in its early workings as it was, men no longer controlled female fertility. Sex was no longer intricately bound up with procreation: it could, and did, become recreational. A world outbreak of permissiveness, as we called it, with some relish. To have sex, in the New Age, you didn’t have to be married. And to be married, you didn’t have to have babies. Though it took a decade or so for people to get used to the idea, and the change to show through in the family-fragmentation statistics. But almost overnight men lost their traditional role, creator and protector of the family. The majority of men had lived up to their former responsibility very well. By and large, pre the nineteen-sixties, if you made a girl pregnant, you married her, and you looked after her and the child. Abortion was illegal, the world wasn’t set up for women to support themselves, and there were no State Benefits: other than that the State provided orphanages for abandoned children. Oddly enough, the moral censure thrown at the lone mother is greater today than it was back in the fifties, or that at least was my experience. Rash you may have been: lovelorn or deceived you probably were, and the consequences were dire enough without others feeling they had to join in, in condemnation.

The second great change is this. For the first time in history we have a preponderance of young men in our population. Young women are, believe it or not, in short supply. More men are always born than women – in this country it’s about one hundred and four males to every hundred females. But once upon a time illness, war and accident so sharply cut down the numbers of young men they were outnumbered by young women and so had a buyer’s market amongst them. It was they who picked and chose and women who did their best to attract. But young male life is safer now, thanks to medical care, the unfashionableness of war, and the trauma wards – and these days in all age groups up to forty-five men increasingly outnumber women: after that age the genders level-step until sixty or so, and with advancing age and man’s shorter lifespan, women once again begin to predominate. Today’s young woman does the sexual picking and choosing: she has the power to reject and uses it no better than the young man ever did. Women discover the gender triumphalism that once was the male’s preserve. See it in the ads. One for Peugeot at the moment: a brisk, beautiful, powerful young woman, followed by her droopy husband. She’s saying to the salesman, ‘It moves faster and it drinks less! Can they do the same for husbands?’ Try role-reversing that one! Does it matter? I suspect it does. It deprives men of their dignity: we all grow into what we are expected to be: this is the process of socialisation. Once women were indeed the little squeaky helpless domestic creatures the culture expected them to be. If we expect men to be laddish and appalling, that is how they will turn out. Where once it was the female fear that she might be left on the shelf, now, as young women get so picky, it is the man’s. We see the arrival of the men’s magazine: in which are discussed the arts of laddishness, flirtation, temptation, seduction: higher up the scale of sophistication, man as father, man as victim, man as sexual partner, man as cook. The way to a career woman’s heart is through her need for someone to do the childcare and the housework. Men are from Mars and women are from Venus but the space ships still need to flit between. Of course we are confused: courtship rituals are reversed. We have no traditions to fall back upon because tradition no longer applies. Poor us.

The third great change came with the seventies wave of feminism, when the personal became the political. In the course of writing a novel ‘Big’ Women (as opposed to ‘Little’ Women), in which I charted in fictional form the course of the feminist revolution, its causes, its progress, and its results. I came to realise the extent of the change we have lived through: to understand how difficult it is to see the wood for the trees.

The novel opens with two young women putting up a poster. A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle. Outrageous and baffling at the time, it turned out to be true. That is to say, she didn’t need one at all. The world has changed, the laws have changed; our young woman is out into the world. She may be lonely at night sometimes but she has her freedom and her financial independence. She can earn, she can spend, she can party. She can choose her sexual partners, but is not likely to stick with them: somehow she outranks them. And she knows well enough that if she has a baby all this will end. And so, increasingly, she chooses not to. The fertility rate, 3:5 in 1901, is now down to 1:8 and falling, below replacement level. Which may be okay for the future of the universe, but isn’t good news for the nation. We lose our brightest and best.

And the fourth thing that happened was that in the last fifty years we stopped being an industrial nation and turned into a service economy, and male muscle became irrelevant. I remember the days when they said women would never work on camera crews because of the weight of the equipment. Now there’s the digital Sony camcorder. Put it in the palm of your hand, your tiny hand, no longer frozen. Anyone can use it.

Adam and Eve and Tony Blair, we all have a lot to cope with. And Pinch Me’s always hiding just around the corner, of course, waiting to spring: changing his form all the time, like the Greek god Proteus, to avoid having to tell us the future.

On being asked by the Features Editor of The Daily Telegraph to write a piece, in the wake of the Countryside March, in the early spring of 1998, to defend the city against the country.

Behind the Rural Myth

The countryside is pretty.

It’s pretty because there are so few people in it. There are so few people in it because there are so few jobs in it. And that’s the nub of the matter.

Yes, you can have a mobile office. Anyone can work from home in these the days of the computer, e-mail, fax, phone and scanner. Who needs the soap-opera of office life? Who wouldn’t want green trees not concrete the other side of the window. So move out. Except it’s insanity, isn’t it? For aloneness, read loneliness. And the blinds stay down to keep the sun off the computer screen. And when the crunch comes you’re the first to go. If the boss has never seen your face why should he bother about the look on it? And try getting the dole in the country: it’s so personal. They don’t just dosh it out like they do in the city: no, they read every word you’ve written on the form you’ve just filled in, and compare last week’s answers, and look everything up in the book – they’ve got time – and say no. And you don’t belong.

The countryside is relaxing.

Yes. You can tell from the clothes of the people who come up on the Countryside March. They don’t have many full-length mirrors in the country; countryfolk being either too haughty and grand to need them or else the ceilings are too low to fit them in. That must be it. The countryside’s not for the vain – heels sink into the mud, like the heels of little Gerda’s pretty red shoes in the Hans Christian Anderson story. Down and down they pulled her, ‘til she stood in the Hall of the Mud King. The countryside’s all practical woolly mufflers and crooked hems and garments it would be a wicked waste to throw out. The country’s full of good worthy people. A good girl in the city is a bad girl in the country. In the country the hairstylists like to turn you out looking like their mother. Well, they do that anywhere in the world, but you get the feeling in the country that they don’t like their mothers very much. Not that it matters; go out for the evening and the place is hardly jumping with film crews and flashbulbs. Who’s to see you?

The countryside is healthy.

No. It isn’t. But it’s unkind to go into that one. Let’s just say, organophosphates have made fools of us all. What goes onto the crops and what goes into the soil? We moved to the country once – kept a tranquil flock of rare-breed sheep which roamed our fields, in the most natural of natural ways. We fed them sheep nuts by hand. What was in the sheep nuts? Ground-up protein from more than one animal of origin. ‘Dip them!’ said the government. We built a trough and pushed the startled, innocent animals in, one by one, dripping and shaking and spluttering, nerve poison all over the place. Oh, thanks!

Pollution drifts over the countryside from the cities, lingers over the valleys. And the pollen count! Good Lord. Just listen to the countryside sneezing and wheezing. The cottage hospital closes. The trauma ward’s an hour away. People live longer in the cities.

And yet, and yet! I know. The warm glow of the setting sun on the old barn walls. The brilliant acid green of early spring. The blackness of night, the great vault of the firmament. The sense of a benign and fecund nature, of being part of the wheeling universe.

But what’s weakness, irrationality. Let’s get back to the brisk facts of the matter.

The countryside is our heritage.

Fact is, it’s shrinking and shrinking fast: suburbia creeps out from the towns. Forty-one percent of British marriages end in divorce, and rising. Twenty-eight percent of us live in single-person households, and rising. We have to build houses and build we do. No choice. And where are the bus services to get us to work, from our new ‘countryside estates’? Not down our road, that’s for sure. And work still stays in the city, so travel we must, and travel we do, and use the car, and know every radio presenter by heart. The countryside becomes somewhere to go, not somewhere to be. A car park here, a car park there: this way the castle, that way the old oak tree, and a fast-food snack as you go! Oh, goodbye, countryside. What rats we are, to leave the sinking ship!

You’re not cut off when you move to the country. Friends will visit.

Well … the friends from the city who came down at first don’t seem to come any more. For a time they overlooked the fact that you’d deserted them, ran out on them, which is what you did, come to think of it. Nobody likes that. looked down your nose at their way of life and left them. So soon the inconvenience gets to them: the overnight bag, the traffic, and the hours that stand between you and them, your strange new friends with straw in their hair wearing long strands of New Age beads, and no proper signal for the mobile, and you’ve been nowhere and seen nothing except the back of the Aga. They settle you in, and their duty done, abandon you. Serves you right.

And the friends who do persist just seem to want a free weekend (well of course they do: what did you expect?) with you cooking and washing up because now you’re in the country that’s the kind of thing you do, isn’t it? Back to nature, back to the sink, and what, no home-made bread? Friends who seemed perfectly civilised for the length of a dinner, reveal over a weekend all kind of gross personal traits. Eat breakfast in their pyjamas, or smoke dope in front of the children, or complain about no dry towels, and quarrel with your neighbours, knowing you’re stuck with them and they can leave.

Let’s compromise. Let’s try a country cottage.

That one used to work, and very well, when husbands had nine-to-five jobs and wives stayed home and looked after the kids. But that’s in the past. Then there was time and energy to work out the logistics of transporting a family, its goods, its bedding, its games and toiletries, to a place some scores of miles away on Friday nights and the reverse process on Sunday evening. Plus guests. And it was lovely, if you were skilled at logistics, that is. Log-fires and cheerful talk and mild drunkenness and happy flirtations and country walks and pink cheeks and a ploughman’s lunch at the pub and no-one worried about drink-and-drive. Oh paradise.