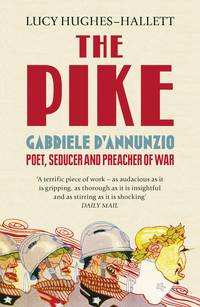

The Pike: Gabriele d’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War

“What can you expect?” he says, as though to excuse himself, “I am Latin.’’’

Being ‘Latin’ is very important to d’Annunzio’s sense of self. Later it will become the dominant theme of his politics. He calls all Anglo-Saxon or Germanic people ‘barbarians’.

‘I’m a terrible one for work,’ he tells Gide. ‘For nine or ten months of the year, non-stop, I work twelve hours a day. I’ve already written a score of books.’ This is only a slight exaggeration. D’Annunzio’s love life is so scandalous that the public thinks of him as a dilettante, but the majority of his time is passed in near solitude and intensely concentrated effort. ‘When I write,’ he says, ‘a sort of magnetical force takes hold of me, like an epileptic. I wrote L’Innocente [his second novel] in three and a half weeks in an Abruzzese convent. If anyone had disturbed me, I would have shot him.’

‘All of these things,’ records Gide, ‘he said without any boastfulness, with gentle sweetness.’

The ability to conjure that same lulling sweetness which entranced Scarfoglio was a gift which never deserted d’Annunzio. Even those who know him well enough to perceive the indifference it masks, find it irresistible. ‘His face lights up in greeting you,’ writes one of his aides years later. ‘And you succumb! You have to succumb! In reality, he doesn’t give a damn!’

January 1901. Turin. In the five years since his encounter with Gide, d’Annunzio has written several plays and his most celebrated novel, and he has embarked on the exquisite sequence of lyric poems, Alcyone (Halcyon). He and Duse are living in adjacent houses in Settignano, in the hills above Florence, their every outing reported by the gossip columns, their incongruous appearance as a couple (Duse is nearly five years older and several inches taller than her lover) repeatedly caricatured.

D’Annunzio’s literary career is at its apogee, and he has begun his transition from poet to politician. In 1897 he contested and won an election in his native Abruzzi. In his electoral campaign he hymned the ‘politics of poetry’. Voted out of office after barely two years, he has been writing the poetry of politics, composing odes in an aggressive and nationalist vein. He is in Turin to give a public reading of the latest of them, a thousand-line tribute to Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti is in Turin as a contributor to the Parisian journal Gil Blas. Marinetti, who will soon become better known as the impresario and spokesman of the futurist movement, is a prolific journalist. Quizzically, Marinetti observes d’Annunzio in his new role as public speaker. Il Vate, the bard, as he now likes to be styled, is thirty-eight, but he could be any age, or ageless. Tightly buttoned into his dark suit he looks like ‘a little ebony idol with a head of ivory’. His eyes ‘sharpened and electrified by the expectation of triumph’ are ‘strangely resplendent’. His face is ‘pale, dried, as though burnt by the fire of Ambition’. This is not an objective description. Marinetti is jealous of d’Annunzio, whom he sees as ‘corsetted by ambition and pride’. He sneers that ‘at all times and in all places Gabriele is dreaming of turning the world upside down with a well-turned phrase’. This is something Marinetti also dreams of doing, and so far d’Annunzio is proving better at it.

D’Annunzio takes his place on the platform, and begins his performance with, thinks Marinetti, the smugness of a cordon bleu chef lifting a lid to display a steaming dish of lentils. He reads very slowly, softly beating time with his fist on the table. His lips are preternaturally red: several contemporaries report that he uses make-up.

The recitation over (it takes an hour and a half) the crowd noisily acclaims him. He half rises to acknowledge the applause, bowing his head. Marinetti notices how the new-fangled electric light is brilliantly reflected off d’Annunzio’s shiny bald pate: a thoroughly modern nimbus for a machine-age hero.

1904, Settignano. Here is another view of d’Annunzio, this one by an anonymous lady whom he takes to bed one afternoon.

He is compulsively promiscuous. Within the last three years he has completed his immense poem-cycle, Laudi. His eight-year-long affair with Eleonora Duse is over and he is spending money more prodigally than ever before. His new lover, an aristocratic young widow, the Marchesa Alessandra di Rudinì, is dangerously ill. It is probably during one of Alessandra’s sojourns in hospital that the unknown lady arrives in response to an invitation with the pointed postscript, ‘I shall expect you alone’.

She is shown into a small sitting room crammed with roses. ‘They were everywhere – in vases, in amphorae, in bowls – and their petals were strewn on the carpets.’ D’Annunzio takes great care over dressing the set for his seductions. Outside the long windows a pergola covered with wisteria casts a mauve veil over the sunlight. The room is suffocatingly overheated, and the atmosphere is further laden with Acqua Nuntia, the scent d’Annunzio has concocted himself from a formula which he claims to have found in a fourteenth-century manuscript. He has had quantities of it made up by a chemist in Florence. It is bottled in Murano glass bottles (also made to the poet’s orders) and labelled (a lot of thought goes into the design of the labels).

The host appears, dressed in a dark blue kimono bordered with black. It is d’Annunzio’s habit to dress in this conveniently removable garment for an assignation and he always provides a kimono for his female visitor’s use. On a small ebony table a large silver tray has been set, bearing a samovar, two cups, and marrons glacés on silver plates. D’Annunzio pours the tea (Chinese, very fragrant), then seats himself crosslegged on the rug by the lady’s chair, takes both her hands in his and embarks upon his seduction. ‘From his gestures, from his voice, there came an invincible wave of desire which engulfed my whole being in an irresistible atmosphere of love.’ There are a number of descriptions of this process: d’Annunzio was a highly persuasive wooer. The anonymous lady feels herself swept ‘into mysterious spheres where there are no laws nor conventions’. Thus conveniently ‘drugged by the delicious poison of the Poet’s musical words’, she somehow swoons her way, without compromising herself by explicitly consenting to sex, into his bedroom.

Their transports ended, d’Annunzio leaves her. ‘A quarter of an hour later I found him in the library, turning the pages of a book.’ Without a word he escorts her to her carriage. She is driven away, feeling ‘the horrid sensation of being discarded like a toy’. On d’Annunzio’s orders, her carriage has been filled, ‘like a rich coffin’, with roses.

Summer 1906. D’Annunzio is in a palatial rented villa, a former home of the dukes of Tuscany, at the seaside near Pisa. His play La Figlia di Jorio (Jorio’s Daughter) has made him not just a literary star but also the voice of his people. ‘Evviva the poet of Italy!’ shouted the audience at its first night.

Alessandra is here, but she is addicted to morphine now and d’Annunzio is already writing daily to his new love, a Florentine countess. For the first time in nearly twenty years he has all three of his sons with him. In the mornings they box in an improvised ring on the beach. D’Annunzio gallops his horse through the pine woods, or swims, or paddles his brand new canoe – throwing himself into each activity with energy which astonishes the younger men. For lunch, served formally by some of the fifteen servants, he changes into a white linen suit, one of the hundred or so he has brought with him. He writes late into the night.

An aspiring poet, Umberto Saba, guest of d’Annunzio’s son Gabriellino, is our witness at this gathering. D’Annunzio, still physically trim at forty-three, greets Saba with exquisite courtesy. Flatteringly, he draws him away from the assembled company and out into the garden, where they sit down together on a stone bench. ‘He asked me, if I was not too tired from my journey, and if it would not be too much of a nuisance for me, to recite some of my poetry?’ This is the acme of Saba’s hopes. He can hardly believe his good fortune. He obliges. D’Annunzio is all compliments. He asks if he may recommend Saba’s work to his editor? Saba, overwhelmed by the great man’s generosity, is close to tears. Everything about the marvellous moment stays with him. Years later it will be as though he can still hear the pine needles creaking beneath their feet.

The conversation continues. There have only been three great poets in Italy, d’Annunzio says – Dante, Petrarch and Leopardi – before, that is, (and he repeats this twice) himself. Saba notices that the poet’s sons are not allowed to call him ‘Papa’. He requires them to address him as ‘Maestro’.

Afterwards Saba posts his precious manuscript. He gets no response. D’Annunzio does not pass his poems on to anyone. He doesn’t even send them back.

September 1909. The Brescia air show: for most of the 50,000 people present their first sight of the amazing spectacle of a man aloft in a flying machine. It is only six years since Wilbur and Orville Wright made their first powered flight, thirteen months since Wilbur first demonstrated their Flyer I in Europe, barely six weeks since Louis Blériot (who is here at Brescia) flew across the English Channel, crash-landing in a vertical fall of sixty-five feet to arrive, with a smashed undercarriage but himself unharmed, in a meadow near Dover Castle. D’Annunzio is ecstatic. Humanity’s conquest of the air, he proclaims, presages, ‘A new civilisation, a new life, new skies!’ A poet is called for, ‘capable of singing this epic’. That poet must be himself. He stages a poetry-reading-cum-press-conference-cum-photo-opportunity at Brescia, reciting verses for the assembled journalists and photographers. The poem, about Icarus, was first published ten years previously: d’Annunzio has been dreaming of flight since he was a schoolboy.

He is at Brescia to gather material for his next novel. He is also planning, courageously (already several aviators have died), to cadge a ride. Now he is being observed by Franz Kafka and his friend Max Brod. The two are holidaying together on Lake Garda. Kafka is depressed: his inspiration has deserted him; his stomach feels to him like a person on the brink of tears. To get him writing again Brod suggests they compose competing accounts of the air show.

The two young men are in the immense crowd on the parched airfield. They both notice d’Annunzio among the ‘sparkling ladies’ and gentlemen on the stands. Brod is struck by d’Annunzio’s ‘feminine charm’, and finds him ‘marvellous through and through’. Kafka is less impressed. By his account d’Annunzio is ‘short’, which is the simple truth, but also ‘weak’ (which may be another way of saying ‘feminine’). Kafka notes that d’Annunzio is ‘skipping’ among the ladies and ‘shyly’ trotting around after Count Oldofredi (one of the show’s organisers).

D’Annunzio isn’t shy, but his body language can be deferential, his posture placatory and insinuating. (Photographs show him with his head dipped slightly to one side, leaning in towards a companion.) Oldofredi is his host for the day, whose consent he must have before he can fly, but he is no ordinary supplicant. To Brod it seems that at Brescia the bigwigs are treating him ‘like a second King of Italy’.

Later that day he makes two short flights, as passenger to the American aviator Glenn Curtiss and the Italian Mario Calderara. He poses for the cameras in a leather flying helmet. Immediately upon landing he gives an interview to the reporter for the Corriere della Sera (his flair for self-promotion never leaves him). Flying, he says, is divine; so divine that even he, the divo of words, is for the moment at a loss as to how to describe it. It is as ineffable as sex.

Increasingly bellicose and nationalist in his politics, d’Annunzio sees – years before the military establishment begins to invest in aviation – the strategic potential of the new flying machines. In the following year he will repeatedly deliver (for handsome fees) a lecture on the need for Italy to achieve Great Nation status by seizing control of the skies.

1910. The bailiffs are in d’Annunzio’s house in Settignano. Pursued by his creditors, himself in pursuit of a long-legged Russian countess with a lovely singing voice and a complaisant husband, announcing to the world that he needs to visit a French dentist, d’Annunzio has decamped to Paris. There his arrival causes quite a stir: he has been a bestselling author in France for two decades. At once he begins to circulate in society, and those he meets are recording their impressions.

He is forty-eight now. To Gide he seems ‘pinched, wrinkled, smaller than ever’. Certainly he needs a good dentist. He has ‘funny little crenellated unhealthy teeth’, notes a French actress on whom he tries his charm. ‘He is the only man I have ever seen with teeth of three colours, white, yellow and black.’ As he has aged his aura of sexual ambiguity has become more marked, intriguing to women, repulsive to most men. (See overleaf.) Several of his new acquaintances remark on his narrow, feminine shoulders and wide womanly hips, his little beringed white hands, his fussy fluttering gestures, his extravagant compliments. ‘An unprepossessing figure,’ notes René Boylesve. ‘He enters like a character from an Italian comedy; one could easily imagine him with a hump.’

For all that, for some he is irresistible. Isadora Duncan testifies that the woman courted by him, ‘feels that her very soul and being are lifted as into an ethereal region where she walks in company with the Divine Beatrice’. The young English diplomat Harold Nicolson, discussing d’Annunzio with two equally snobbish European noblemen, decides that the petit-bourgeois poet is ‘a chap one couldn’t know’, but, having heard him declaim his verses in an aristocratic drawing room, the bisexual Nicolson is instantly besotted. Nicolson leaves the party abruptly and walks along the quays, ‘still fervent with excitement’, d’Annunzio’s voice ringing in his ears ‘like a silver bell’.

There are Parisians who see beyond the bewitching surface. D’Annunzio accepts advances for books he will never write. He decamps from hotels leaving bills unpaid. Maurice Barrès, the French nationalist writer whose work d’Annunzio has correctly been accused of plagiarising, plainly sees the self-serving, exploitative side of the poet. ‘He is like a bird which scratches about for seed with its hard beak … this hard little soldier, this grasping conqueror, pecking and hurting the palm of my hand.’ Others sense his weariness. His greatest loves are past; his best poetry is written; in leaving Italy he has lost his role as national figurehead. The flamboyant homosexual Count Robert de Montesquiou has taken him up, and is introducing him to Parisian high society, but notices that occasionally his mask drops. Then one sees ‘something withered … the nostrils become deformed like those of a face on a shield that has been dented in combat, and the corners of the mouth express unutterable horror’.

Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes are in Paris, performing Cleopatra, choreographed by Fokine with designs by Léon Bakst. The title role is mimed by Ida Rubinstein – a bisexual Russian beauty. She comes on in an immense blue wig and drifts of diaphanous, gem-scattered gauze, most of which she sheds before the evening is out. D’Annunzio is in the audience with de Montesquiou. After the performance they go backstage, where Rubinstein is holding court still clad only in massive ‘barbaric’ jewellery and an exiguous amount of chiffon. Barrès is there, and Edmond Rostand, and other literary luminaries, all in evening dress. D’Annunzio takes up the story. ‘Seeing at close quarters those marvellous naked legs, with my usual boldness I threw myself to the ground and – quite oblivious of my swallow-tail coat – kissed the feet, rose, still kissing, from the ankle to the knee, and up along the thigh to the crotch, kissing with lips as swift and supple as a flautist’s scurrying over the stops of a double flute. Tableau! Scandale!’ The bystanders are embarrassed. Rubinstein is amused. D’Annunzio lifts his eyes (even when standing upright he is a good six inches shorter than she) and sees, beneath the great tangled blue cloud of false hair, that she is smiling, and that she has a ‘dazzling’ mouth.

Soon they will be having some sort of a sexual relationship (in their private encounters, as well as this public one, it is mostly a matter of d’Annunzio’s mouth and Rubinstein’s nether parts) and she will be playing the title role in his The Martyrdom of St Sebastian. The saint has long featured in d’Annunzio’s sexual fantasies. Now he converts them into a long, lush piece of music drama, with a score by his new friend Claude Debussy and designs – again – by Bakst. The Bishop of Paris forbids his flock to attend it. It is placed on the Papal Index of books no good Catholic may read.

March 1915. Since the outbreak of war, d’Annunzio, who believes only ‘a great conflict of the races’ can purge society of its decadence, has been calling from Paris for Italy to enter the war on the side of Britain and France (its ‘Latin Sister’). He is planning to return to Italy, but as he awaits his moment he accompanies the Italian journalist, Ugo Ojetti, to Reims, to see the venerable cathedral which went up in flames while under German occupation the previous September. Ojetti has obtained a pass, and a motor car. He stops off at the seventeenth-century hôtel particulier in the western Marais, where d’Annunzio has an apartment cluttered with oriental artefacts – a visitor has dubbed it ‘the House of the Hundred Buddhas’. A servant comes out first with several suitcases (d’Annunzio never travels light) and hampers full of food. Then d’Annunzio appears, ‘elegant and glossy as ever’, in an outfit which (unlike Ojetti’s suit and trilby) has a vaguely military air: his civilian status shames him. He is wearing a motoring cap, riding breeches with grey puttees, and a rich brown overcoat lined with curly yellow fox fur.

They drive through the ‘lunar landscape’ of the battlefields to Reims. Everywhere there are dead horses, their bellies inflated, their legs in the air. The great Gothic cathedral is roofless, its windows empty, its stones blackened. Guns are audible: they are not far from the front. D’Annunzio is silent and attentive. He picks up a shard of stained glass, a twisted strip of lead, a carved stone flower fallen from one of the pinnacles (all three will be on his desk at the time of his death twenty-three years later). He scrambles over sandbags to view the statues which he knows are there; he has been studying the guidebooks assiduously. He is making notes: ‘Pigeons fly up as though the wing of an angel had suddenly opened.’

This is his first visit to Reims but he has already written an account of the fire, each paragraph introduced with the lie ‘I saw …’. He knows what a potent image of German ‘vandalism’ the blackened ruin of the cathedral makes, and he understands how his own celebrity endorses it. His pseudo-eyewitness account was useful propaganda: it didn’t need to be true.

On the return journey – still, in that deathly landscape, the aesthete and poet – d’Annunzio notes how the road curves like the banderoles in mediaeval depictions of saints.

17 May 1915. Rome. The Capitol. D’Annunzio has returned after five years in France, re-energised. He is past fifty, but the most exciting period of his life is only just beginning. Europe is at war and he has found a new medium – the spoken word; a new persona – that of national hero; and a new mission – that of urging his compatriots to be great. Italy is still neutral. Ever since d’Annunzio arrived in the country twelve days ago he has been delivering oration after oration, each one more virulent in its contempt for the peace party, each one more bellicose.

Now he is speaking at the heart of ancient Rome to an already volatile crowd. D’Annunzio himself recalls the scene months later as he lies wounded: ‘Faces, faces, faces without number run past my bandaged eyes, like hot sand pouring through a fist. Is it not the Roman crowd, of that May evening on the Capitol? Enormous, rippling, howling?’

Fastidious to the point of neurosis, d’Annunzio has always been shudderingly preoccupied with dirt. Now he translates that private anxiety into political rage. In a virtuoso display of his immense vocabulary, he loads his speeches with synonyms for filth. The old order reeks and must be utterly destroyed. Cautious politicians are to be disposed of like rotten meat. ‘Sweep away all the filth! Into the sewer with all that is vile!’ Italy, its government, its entire political system, is dirty, foul, filthy, polluted, besmirched, sullied, soiled, stinking, fetid, contaminated, shitty, rancid, infected, diseased, putrid, rotten, corrupt, festering and defiled. He calls for a cauterisation by fire, a holocaust (a word he uses often), a great outpouring of blood to purge the stench of corruption.

He is beside himself. ‘I feel my own pale face burn like a white flame. There is nothing of me in me. I am as the demon of the tumult … Each of my words resounds beneath my cranium like the reverberation of curved metal.’

As his tirade reaches its climax he produces a prop, a sword which once belonged to Nino Bixio, the most aggressive of Garibaldi’s lieutenants.

‘I take it and draw it … I press my lips to the naked blade … I abandon my soul to delirium.’

The crowd weeps and howls. D’Annunzio thunders on. He is urging his listeners to ensure, by any means, up to and including murder, that the appeasers should not be allowed to take their seats in parliament again. ‘Make out lists. Proscribe them. Be pitiless. You have the right.’

His speech triggers a riot. Hundreds of people are arrested. One of them is Marinetti, who has declared in his ‘Futurist Manifesto’ that he would celebrate ‘the multicoloured, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capital’. Another is a magazine editor named Benito Mussolini.

One week later Prime Minister Salandra declares that Italy is at war.

August 1917. War. As a roving ‘liaison officer’ d’Annunzio has been on night manoeuvres on board warships in the Adriatic, and has been down in a submarine. He has been repeatedly under fire in the terrible battles in the mountains and along the River Timavo, and he has flown repeatedly. He has survived a plane crash after which he had to lie motionless in a darkened room for months, and which has left him blind in one eye. Even Ernest Hemingway, who can’t stand his high-faluting rhetoric, grants that he has been ‘divinely brave’.

This is d’Annunzio’s account of a mission flown in pursuit of Austrian troops in the Slovenian mountains. He is now in command of a squadron of fighter planes. The letter is to his latest lover, mistress of one of Venice’s great palaces, whom he calls Venturina because her gold-flecked, tawny eyes remind him of one of the colours used by the Murano glass-makers (he is a discriminating collector of glass): ‘I think Venturina will be pleased with her friend. It was an inferno of fire. I went down to 150 metres over the enemy infantry in order to machine-gun them. I could make out their uniforms, and the flap of canvas they wear hanging down the back of their necks to keep off the sun … Miracle! A bullet heading for my head hit the bar at the back of the cockpit, and rebounded. I heard the clear ping it made, and turned round. The steel bar was dented. Another bullet passed through the canvas between my legs. Innumerable others have made holes in the wings, splintered the propellers, snapped the cords. And we are unharmed!’

Twelve days earlier, d’Annunzio, ever attentive to the ritual of warfare, has taught his squadron a new battle cry. Instead of the ‘Ip, Ip, Ip, Urrah!’ which he finds crude and barbarous, he has ordered them to shout the Greek: ‘Eia, Eia, Eia, Alalà!’ It is, he claims, the battle yell of Achilles. He has found it in Aeschylus and Pindar. He has used it in his plays. Now he is demanding that the men under his command give the shout standing upright in the cockpits of their flimsy little wood and canvas planes.