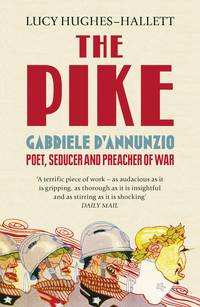

The Pike: Gabriele d’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War

The aircraft circle round, flying beneath the enemy troops on the high mountain passes and then climbing again ‘up the sides of Mount Hermada like a cart crawling up a slope’. They return to base to load up with more bombs, and fly back into battle over the Austrians’ big guns. ‘We saw shells passing the prow and the stern like ugly big rats tunnelling through the air.’ This is the fiercest fire d’Annunzio has ever yet endured. It is ‘a marvellous hour, which I would not exchange for any other I have lived’.

April 1919. The war is over. The peace-makers are still conferring at Versailles, carving up the remains of the defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire. Ever since the war ended d’Annunzio has been crying out that Italy is being cheated of its fair share, that its victory has been ‘mutilated’. Now he is in Venice, speaking in the Piazza San Marco, calling upon Italians to take up arms again and lay claim to the territory (Istria, Croatia and the Dalmatian coast) which the newborn state of Yugoslavia is claiming, but which he calls ‘Italy’s left lung’. The Irish Italophile Walter Starkie is there and, at first, is horribly disappointed by d’Annunzio’s appearance. ‘A dwarf of a man, goggle-eyed and thick-lipped – truly sinister in his grotesqueness, like a tragic gargoyle.’ Starkie, like many others, wonders incredulously: ‘Is this the man that Duse loved?’

D’Annunzio begins to speak; at once Starkie is ‘fascinated’. D’Annunzio plays on the crowd ‘as a supreme violinist does upon a Stradivarius’. He pretends to be reluctant to speak. ‘The time for words has passed.’ But he has come prepared, bringing with him an enormous Italian flag, which he employs as a prop in a brilliantly manipulative, quasi-liturgical performance. His bearing is priestly, his delivery carefully measured. ‘Never a hurried, jerky gesture: occasionally one arm raised slowly as though wielding an imaginary wand.’ The effect is mesmerising. ‘The tones rose and fell in an unending stream, like the song of a minstrel, and they spread over the vast audience like olive oil on the surface of the sea.’

This oil is designed not to calm troubled waters but to set them surging. Very, very gradually, his voice rising in a patiently extended crescendo, d’Annunzio strings his public’s emotions ever tighter. He incites the crowd to call out in reply to him, involving them in their own bewitchment. His own record of the speech notes their responses. ‘All the people cry out “We want it’’’; ‘the whole piazza resounds to unanimous acclamation’; ‘frenetic cheering’; ‘the people cry “Yes’’’; ‘the people cry “Yes!” again, more loudly’; ‘the people repeat the shout and brandish their flags’. As he reaches his thundering climax, writes Starkie, ‘the eyes of the thousands [are] fixed upon him as though hypnotised by his power’.

September 1919. D’Annunzio has taken action. He has marched into Fiume and made himself ruler of the tiny but now world-famous city-state. Among his new acolytes is Giovanni Comisso, another poet (some thirty years younger than d’Annunzio), who was serving with the Allied garrison when d’Annunzio marched into the city, and who promptly deserted to join him.

Comisso is there when d’Annunzio arrives at the Governor’s Palace amid a din of bands playing and crowds singing. Stepping out of the car he looks small and, feverish as he is, ‘very, very weak’. Comisso joins the throng who jostle along behind d’Annunzio up the marble staircase to the wide balcony from which he is to address the people massed below. To Comisso’s wonder the frail invalid begins to speak ‘with incredible force’, declaring that Fiume is the only brightness in a mad, vile world. The assembled crowd weep and laugh and howl out their enthusiasm. ‘This man convinced me,’ writes Comisso ‘as though he was one of the prophets of olden times.’

A few days later Comisso is shaving when he hears a hubbub outside his window and leans out, his shirt open, his face covered with soap, to see what’s causing the commotion. Down in the street soldiers are milling around a very small man wearing the jaunty-brimmed felt hat of the Alpine troops. ‘He seemed like a boy, agile and restless. He kept taking one of the others by the arm and having himself photographed.’ It is d’Annunzio, turning some of his prodigious energy to the job he does so well – making a spectacle of himself. When he arrived in the outskirts of Fiume he paused to allow a camera crew to catch up. One of his first measures on taking power in Fiume is to establish his press office. During the next fifteen months d’Annunzio’s image, carefully groomed by himself, will appear in newspapers all over the Western world.

November 1920. The aristocratic English man of letters Osbert Sitwell has come to Fiume, curious to see what ‘the man who has done more for the Italian language than any writer since Dante’ has made of his city-state. Sitwell finds the streets full of colourful desperadoes: ‘Every man seemed to wear a uniform designed by himself; some wore beards and had shaven heads like the commander, others cultivated huge tufts of hair, half a foot long, waving out from their foreheads, and a black fez at the back of the head. Cloaks, feathers and flowing black ties were universal, and all carried the Roman dagger.’

Sitwell succeeds in securing an audience. He passes through a pillared hall, full of palm trees in ‘pseudo-Byzantine flower pots … where soldiers lounged and typists rushed furiously in and out’. In an inner room ‘almost entirely covered with banners’, he finds two more-than-lifesize, carved and gilded saints from Florence, a huge fifteenth-century bronze bell, and the Commandant (as d’Annunzio now likes to be called) in military grey-green, his chest striped with the ribbons of his many medals. He seems nervous and tired. But, bald and one-eyed as he is, ‘at the end of a few seconds one felt the influence of that extraordinary charm which has enabled him to change howling mobs into furious partisans’.

Since Sitwell arrived in Fiume the great conductor, Arturo Toscanini, has brought his orchestra to the town. To celebrate Toscanini’s visit, d’Annunzio lays on a mock battle which is as lethal as an ancient Roman circus: 4,000 men take part, attacking each other with real grenades. The orchestra, which initially provides a musical accompaniment (Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony), becomes involved in the fighting. Over a hundred men are injured, including five musicians.

Now d’Annunzio, discussing the event with Sitwell, explains that his legionaries are ‘weary of waiting for battle. They must fight one another.’ But he doesn’t really want to talk about the mayhem around him. Sitwell’s visit, he says, is welcome as an alleviation of his ‘great loneliness’. Soldiers are all very well, but he misses the fellowship, not of equals (he does not, in his opinion, have any equals) but of well-informed admirers. He quizzes Sitwell about the new English poets (one of the best of whom is Sitwell’s sister, Edith). They talk about Shelley, and about English greyhounds.

January 1921. The Italian government, on whose behalf d’Annunzio claims to have annexed Fiume, but for whom his escapade has been embarrassing abroad and destabilising at home, has sent troops and a warship to dislodge him. For years d’Annunzio has been leading crowds in chants of ‘Fiume or Death!’ but he hadn’t expected his opponent to be his own people. After five days of fighting he agrees to withdraw. The Italian populace of Fiume, some 12,000 people, turn out to see him leave. ‘Under a deluge of flowers,’ according to a supporter, ‘he forces his way through a city in tears.’ Later that day he arrives by car, alone but for his driver, at a landing stage on the Venetian lagoon. His long-serving aide, Tom Antongini, and an officer of his Legion, have brought a motor launch to meet him. The light is failing. Land and water are both shrouded in mist. D’Annunzio is enveloped in a grey cape and fur motoring cap. To Antongini he seems ‘suddenly aged’ and barely conscious. He embraces the two men and goes silently aboard the launch.

They make the short journey to the Palazzo Barbarigo. D’Annunzio has a rented apartment there, but it is less a home than a furniture depository, being crammed with the contents of the house in France that he left six years previously. Nine lorries were required to bring the mass of his possessions to Venice – the thousands of books, the hundreds of Buddhas, the scores of reproductions of paintings of St Sebastian. Now they are stacked up, higgledy-piggledy, in the lofty rooms. Documents spill from boxes. Dusty carpets are heaped in a corner. D’Annunzio’s housekeeper has sought to please her master by heating the place to his preferred inordinate temperature. As they enter, Antongini and the officer begin to sweat.

The next day d’Annunzio summons six of his acolytes. He is tetchy, exasperated by the mess surrounding him. He orders them off to search northern Italy for a new home for him. He needs a grand piano, a bathroom, a laundry, plenty of wood and coal, an enclosed garden. ‘If within eight days,’ he says ‘none of you has found a suitable house for me, I shall throw myself into the canal.’

January 1925. D’Annunzio is in the house on the mountain slopes above Lake Garda, where he will spend the rest of his life and which he will gradually transform into a bizarre piece of installation art: part display case for his vast and eclectic range of possessions; part externalisation of his own multi-faceted personality; part war memorial, part garden of earthly delights; part mausoleum. He calls it the Vittoriale.

Benito Mussolini has taken his political place, bullying his way to the premiership by marching on Rome in October 1922. It suits Mussolini that the Italian public should believe that d’Annunzio is whole-heartedly behind the new regime, but in truth they are suspicious of each other. The poet is a maverick, and still dangerously influential: he has to be kept on side. His insatiable need for money presents a point of leverage. ‘When a decayed tooth cannot be pulled out it is capped with gold,’ says Mussolini. He acts accordingly.

Mussolini greatly increases the strangeness of the Vittoriale by contributing to the jumble of objects it contains some Brobdignagian souvenirs. First comes the plane in which d’Annunzio once overflew Vienna (d’Annunzio will build a rotunda especially to house it). Next is the motor boat in which d’Annunzio made a daring raid on the Austrian fleet: d’Annunzio roars up and down the lake in it (and catches a bad cold). Next, dismantled and transported on over twenty flat-bed railway trucks, comes the forward half of a battleship, the Puglia. Offloaded at the railway station in Desenzano and laboriously transported piecemeal along the lake shore and up the mountainside to d’Annunzio’s fastness, it is there reassembled. Set in concrete, its missing rear recreated in stone, it juts out from the side of the cypress-covered slope above d’Annunzio’s rose garden as though breaking through a petrified wave. The gift comes complete with a set of real live sailors, whom d’Annunzio drills on deck.

And now we can see d’Annunzio with our own eyes. On YouTube we can watch a Fox Movietone newsreel showing a little party he gives on the Puglia’s deck soon after its installation. Proceedings open with the tolling of a great bell. Then comes a six-gun salute, smoke from the ship’s cannon cloaking the hillside. The host appears on deck, in military uniform with a chest full of decorations, smilingly escorting some ladies in cloche hats. A string quartet plays: d’Annunzio listens attentively (the camera politely staying on the side of his good eye). He is stouter now, and slightly stooped. He plays a few notes on a clarinet. Cut. Now d’Annunzio is cackling merrily, revealing that he is almost toothless. People are often surprised – given the total humourlessness of his writing – to find how playful he can be. He has been invited to recite some verse for the film crew. He waves his hands and gabbles, amidst more laughter, the opening lines of Dante’s Inferno, before turning back to his female friends.

Only three years before his own accession to power, Mussolini wrote to d’Annunzio suggesting the overthrow of the Italian monarchy and the establishment of a ‘Directory’ with d’Annunzio as president. It was d’Annunzio who was the Duce then, while Mussolini was content to act as his enforcer. Now d’Annunzio is a lost leader. Throughout the 1920s there will be people looking to him to exploit his immense public following and give them a lead: fascists dismayed by the compromises Mussolini makes on his way to consolidating his power; anti-fascists who believe the poet could become the figurehead of a less brutal regime. They look in vain.

September 1937. The railway station in Verona. Mussolini is on his way back to Rome after visiting his new ally, Adolf Hitler, and showing himself to the German people. D’Annunzio – vehemently anti-German all his life – has described Hitler to Mussolini as ‘a ferocious clown’. All the same, although he seldom leaves the Vittoriale now, he travels from Garda to pay his respects. He is seventy-four, and although he is still goatishly proud of his sexual prowess, he is dreadfully aged, by time, but also by syphilis and by the quantity of cocaine he has been taking.

A newsreel, here described by d’Annunzio’s French biographer Philippe Jullian, records the occasion: ‘D’Annunzio, on the arm of the architect Maroni, shuffles along the red carpet up to the carriage window, through which the Duce is leaning. With the smile of an ogre, Mussolini takes the poet’s hand in his.’ Mussolini, descending from the train, makes his way towards a balcony from which he is to address the assembled crowd. ‘The little old man toddles after him, chattering away and waving his withered hands in the air; Mussolini, without slowing down, smiles down at him from time to time, but the ovations of the crowd prevent him from hearing a word of what d’Annunzio is saying.’ Eventually the Duce pushes brusquely ahead, pointedly not inviting d’Annunzio to join him, leaving the poet to struggle back to his car through the oblivious crowd.

According to Mussolini’s spy at the Vittoriale, what d’Annunzio claims to have been trying to say to the Duce was: ‘I admire you more than ever for what you are doing.’ But Maroni, whom d’Annunzio trusts, reports that he returns to the Vittoriale in a state of acute depression, murmuring: ‘This is the end.’ Five months later he will be dead.

SIX MONTHS

JUST AFTER DAWN on Good Friday 1915, Fly, Gabriele d’Annunzio’s favourite among his several dozen greyhounds, died in a veterinary clinic in Paris. The poet had stayed up most of the night while Fly leaned trembling against him, one of her legs so swollen she couldn’t lie down. Eventually the vet declared that he must ‘liberate’ her. While he did so d’Annunzio walked the streets. It was a public holiday, the most doleful festival in the Christian calendar, and Paris was anyway three-quarters empty: most of the city’s well-to-do inhabitants had fled when the government decamped to Bordeaux the previous autumn. What few people d’Annunzio passed were all men in uniform, and wounded. He stopped at the window of a musical instrument shop to admire some violins (as a connoisseur of music and of fine workmanship he was very interested in the luthier’s craft). Their delicate lines, their gilded darkness, reminded him of his dear dog.

Back at the surgery, the attendant uncovered Fly’s body for him. Her eyes, always before so adoringly fixed on him, were ‘blackened slots’. He had the corpse wrapped in cotton wool, then in a linen sheet, then in red damask, and finally laid in a white lacquered casket. As the workman nailed down the lid he remembered how much Fly had feared being alone in the dark. With the coffin in the back of his car he drove very slowly out to the farm near Versailles where his more-or-less-discarded mistress, Nathalie Goloubeff, cared for his dwindling pack of hounds. Since France had gone to war many of them had had to be put down for lack of food.

The grave was dug. Nathalie laid a basket of forget-me-nots and ivy at Fly’s head. D’Annunzio’s notebook entry for that day is listlessly bleak: the crackle of machine-gun fire (they were very near the front); a cock crowing; smoke drifting. ‘The mole hills, pale-coloured like dried-out clay … this terrible life … the throbbing of the aeroplanes, Fly’s poor eyes already putrefying … a sadness beyond words.’ Afterwards d’Annunzio ate breakfast with Nathalie, whom he had followed to France five years earlier, and with whom he still sometimes passed delicious nights. They were quiet. D’Annunzio was watching the dogs, Fly’s children and grandchildren, and thinking of the hound’s svelte body beginning to rot underground.

D’Annunzio writes about his dogs with a tenderness he seldom displays in writing about his women. Within days he would part from Nathalie, never to see her again; his references to her in his subsequent writings are more irritable than elegiac. That day of muted private emotion fell in the middle of a month of whirling excitement in his public life. As he buried Fly in a spoiled field he was in the midst of burying a phase of his life of which he was tired, and impatient for the beginning of a new one.

Since the outbreak of war the previous summer he had been stalled, stuck in the wrong place, unsure of his role, feeling his age (he was fifty-two). But on 7 March 1915 he finally got around to looking at a letter he had received days before (recipient of enormous quantities of fanmail, he often left his post unopened for weeks, or for ever). The letter contained a photograph of a monument to be erected at the harbour town of Quarto, near Genoa, from which Giuseppe Garibaldi and his followers had embarked for Sicily. The Sicilian expedition was, and is, the most thrilling episode in modern Italy’s myth of origin. In 1860, without the sanction of any government, at the head of a troop of just over a thousand ill-equipped volunteers, Garibaldi landed in Sicily. Over the next few months he drove the armies of the Bourbon King of Naples out of southern Italy, beginning the process which would lead to the creation of a free and united Italy.

Garibaldi was as famously beautiful as d’Annunzio was notoriously odd-looking. Garibaldi was renowned for his asceticism and his absolute integrity: after making himself dictator of half of Italy he took nothing for himself but a sack of seed corn. D’Annunzio was an inveterate breaker of contracts and non-payer of debts who bought suits by the dozen and shirts by the hundred. But the two men had some important things in common, among them prodigious sexual energy and a detestation of the Austrians (for centuries overlords of much of Italy). In Paris in 1915, d’Annunzio was in contact with Peppino Garibaldi, the great man’s grandson, who was commanding a legion of Italian volunteers fighting alongside the French. D’Annunzio had been waiting for the right occasion for his return to Italy. The letter, which so narrowly escaped the waste-paper basket, gave him his opportunity. The monument was to be unveiled on 5 May, the fifty-fifth anniversary of Garibaldi’s setting out. Would d’Annunzio, the organisers wondered, consider returning to his home country to speak on the occasion? ‘I opened the letter. I read it, and lo! Everything turned bright!’

When the war began, the previous year, Italy remained neutral. Prime Minister Antonio Salandra and Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino, aware that their armed forces were ill-prepared for conflict, announced that they would observe the terms of the 1882 Triple Alliance, whereby Italy had agreed with Austria and Germany to refrain from making war on each other. To d’Annunzio that neutrality seemed shameful. Italy should fight, not for advantage but as a matter of pride. Too many people around the world thought of the country as ‘a museum, an inn, a holiday destination, a horizon touched up with Prussian blue for international honeymoons’. They must be shown otherwise. Throughout the winter of 1914/15, d’Annunzio had been calling on the Italian government, through the pages of journals both French and Italian, to intervene on the side of France (Britain and Russia’s part in the war was of no interest to him) against the Teutonic ‘horde’. ‘This war is not a simple conflict of interests, which might be transient, sporadic or illusory,’ he wrote, ‘it is a struggle of races, a confrontation of irreconcilable powers, a trial of blood.’

The French government was naturally eager to encourage d’Annunzio to bring his compatriots into battle on their side. The evening before he read the letter from Genoa, a French official, Jean Finot, came to see him. D’Annunzio didn’t like him much. ‘A little hunched man, held upright by a kind of dried-out vanity.’ Nor was he impressed by the plan Finot had come to discuss. Peppino Garibaldi’s volunteer legion had been fighting heroically: a quarter of the men, including two of Garibaldi’s other grandsons, had been killed. Now the survivors were to be sent home to rouse their fellow Italians to action. Madame Paquin, the couturier, had promised 2,000 red shirts of the kind that the great Garibaldi’s own men had worn half a century before, but made of silk this time. The venture was something like a coup d’état, something like a piece of political theatre. As the former it seemed incompetent: as the latter it felt muzzily ill-directed. D’Annunzio was anxious. After Finot left he applied a mustard plaster to his chest – he had a bad cough – and went to bed, but lay for a long time restless. All his life his moods oscillated between prodigious energy and depression. On this night he was very low. He waited for sleep, ‘as for death’.

When he read the letter from Genoa the following morning he was instantly high again. ‘I will go. I will lead the Garibaldini Legion, the red wave,’ he told his notebook. ‘To reach Quarto … to cross the Tyrrhenian Sea with a ship loaded with blood eager to be spilled!’ An ‘Apollonian providence’ had come to his aid.

Peppino Garibaldi came to see him in the afternoon. The two men paced around the room, both of them too excited to sit down. D’Annunzio small, neatly groomed as always; Garibaldi tall, with his deeply lined face and brilliant eyes, in the blue tunic and red breeches of a colonel in the French army. D’Annunzio expounded his vision: ‘Two thousand young men in arms … encircling the solemn monument ready to set out from there to conquer and to die.’ He himself as creator, director and star of this martial show. ‘It is impossible that Italy, however blind or deaf, does not see the sign, does not hear the appeal, rising up from the rock of Quarto.’ Garibaldi was equally moved. It will be a flame, he said, or a poem. D’Annunzio, who had woken that morning feeling seedy, with a touch of ‘the humiliating little complaint’ (either piles or a recurrence of the venereal disease which he had contracted the previous year), ended the day enraptured, swept away on ‘a torrent of interior music’.

Just over three weeks later came the sad day of Fly’s death, and a mournful Easter spent with Nathalie, followed by the melancholy process of packing up. ‘Life flows from the house as though from an open vein,’ wrote d’Annunzio, watching the removal men dismantle his Parisian home. He gave away some of his best greyhounds – two of them to Pétain, the future Marshal. D’Annunzio was, as usual, badly in need of money. To finance his journey he pawned some splendid emeralds which Eleonora Duse had given him. With another month to go before he was due in Quarto, he set out for his villa on the Atlantic coast at Arcachon. There he poured his energies into writing two furiously bellicose articles and the speech for Quarto, and into his last love affair on French soil, with a surgeon’s daughter, a fine horsewoman (d’Annunzio admired ‘Amazons’) to whose presence in the neighbourhood his housekeeper-cum-concubine-cum-procuress Amélie Mazower (whom he called ‘Aélis’) had alerted him.

Back in Paris, assiduous as ever in self-promotion, he gave a press conference. The Revue de Paris correspondent was positively shocked by the splendour of his wardrobe. His secretary had been busy chasing up the suits he had on order from his tailor, and his accounts for that month reveal he had also bought a prodigious number of new cravats. He delivered the text of his speech to Salandra, the Italian premier, and to newspaper editors in Paris and Milan, with strict instructions that it was to be embargoed until the morning of 5 May. He told the editor of Le Figaro, ‘the die is about to be cast’. The verbal flourish reveals that he saw himself as a second Julius Caesar, imposing a heroically martial destiny on an unwilling Rome.