The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

If the British could not defeat France, the revolutionary government could not in its turn undermine the enemy’s naval mastery. Early attempts to invade Ireland and to raid the western coasts of England had come to little, although that was due as much to the weather as to local defences. Despite the temporary fright over the 1797 suspension of cash payments, the British credit system held firm. The entry of Spain and the Netherlands into the war on France’s side led to the smashing of the Spanish fleet off Cape St Vincent (February 1797) and to the heavy blows inflicted upon the Dutch at Camperdown (October 1797). France’s new allies also had to endure the progressive loss of their colonies overseas – in the East and West Indies, and at Colombo, Malacca, and the Cape of Good Hope, all of which provided new markets for British commerce and additional bases for its naval squadrons. Unwilling to pay the high price demanded by the French government for peace, Pitt and his fellow ministers resolved to fight on, introducing income tax as well as raising fresh loans to pay for what – with French troops assembling along the Channel coast – had become a struggle as much for national survival as for imperial security.

Here, then, was the fundamental strategical dilemma which faced both France and Britain for the next two decades of war. Like the whale and the elephant, each was by far the largest creature in its own domain. But British control of the sea routes could not by itself destroy the French hegemony in Europe, nor could Napoleon’s military mastery reduce the islanders to surrender. Furthermore, because France’s territorial acquisitions and political browbeating of its neighbours aroused considerable resentment, the government in Paris could never be certain that the other continental powers would permanently accept the French imperium so long as Britain – offering subsidies, munitions, and possibly even troops – remained independent. This, evidently, was also Napoleon’s view when he argued in 1797: ‘Let us concentrate our efforts on building up our fleet and on destroying England. Once that is done Europe is at our feet.’76 Yet that French goal could be achieved only by waging a successful maritime and commercial strategy against Britain, since military gains on land were not enough; just as the British needed to challenge Napoleon’s continental domination – by direct intervention and securing allies – since the Royal Navy’s mastery at sea was also not enough. As long as the one combatant was supreme on land and the other at sea, each felt threatened and insecure; and each therefore cast around for fresh means, and allies, with which to tilt the balance.

Napoleon’s attempt to alter that balance was characteristically bold – and risky: taking advantage of Britain’s weak position in the Mediterranean in the summer of 1798, he invaded Egypt with 31,000 troops and thus placed himself in a position to dominate the Levant, the Ottoman Empire, and the route to India. At almost the same time, the British were distracted by yet another French expedition to Ireland. Each of those strokes, had they been fully successful, would have dealt a dreadful blow to Britain’s shaky position. But the Irish invasion was small-scale and belated, and was contained in early September, by which time all of Europe was learning of Nelson’s defeat of the French fleet at Aboukir and of Napoleon’s consequent ‘bondage’ in Egypt. Just as Paris had suspected, such a setback encouraged all who resented French predominance to abandon their neutrality and to join in the war of the Second Coalition (1798–1800). Besides the smaller states of Portugal and Naples, Russia, Austria, and Turkey were now on the British side, assembling their armies and negotiating for subsidies. Losing Minorca and Malta, defeated in Switzerland and Italy by Austro-Russian forces, and with Napoleon himself unable to achieve victory in the Levant, France appeared to be in serious trouble.

Yet the second coalition, like the first, rested upon shaky political and strategical foundations.77 Prussia was noticeably absent, so that no northern German front could be opened. A premature campaign by the king of Naples led to disaster, and an ill-prepared Anglo-Russian expedition to Holland failed to arouse the local population and eventually had to retire. Far from drawing the conclusion that continental operations needed to be more substantial, and acutely conscious of the financial and political difficulties of raising a large army, the British government fell back upon its traditional policy of ‘descents’ upon the enemy’s coastline; but their small-scale attacks upon Belle-Isle, Ferrol, Cádiz, and elsewhere served no useful strategical purpose. Worse still, the Austrians and Russians failed to cooperate in their defence of Switzerland, and the Russians were driven eastward through the mountains; at that, the czar’s disenchantment with his allies intensified into a deep suspicion of British policy and a willingness to negotiate with Napoleon, who had slipped back into France from Egypt. The withdrawal of Russia left the Austrians to receive the full weight of the French fury, at Marengo and Hochstadt (both in June 1800), and six months later at Hohenlinden, compelling Vienna once again to sue for peace. With Prussia and Denmark taking advantage of this turn of events to overrun Hanover, and with Spain launching an invasion of Portugal, the British stood virtually alone in 1801, just as they had been three years earlier. In northern Europe, Russia, Denmark, Sweden, and Prussia had come together in a new Armed Neutrality League.

In the maritime and extra-European campaigning, on the other hand, the British had again done rather well. Malta had been captured from the French, providing the Royal Navy with a vital strategical base. The Danish fleet, the first line of the new Armed Neutrality League’s scheme to exclude British trade from the Baltic, was smashed off Copenhagen (although the assassination of Czar Paul a few days earlier spelled the end of the League in any case). In that same month of March 1801 a British expedition defeated the French army at Alexandria, which afterward led to a complete French withdrawal from Egypt. Farther afield, British forces in India overwhelmed the French-backed Tipu in Mysore and continued to make additional gains in the north. French, Dutch, Danish, and Swedish possessions in the West Indies also fell into British hands.

Yet the lack of a solid continental ally by 1801 and the inconclusive nature of the Anglo-French campaigning caused many politicians in England to think of peace; and those sentiments were reinforced by the urgings of mercantile circles whose commerce was suffering in the Mediterranean and, to a lesser extent, in the Baltic. Pitt’s resignation over Catholic emancipation hastened the move toward negotiations. In Napoleon’s calculation, there was little to be lost from a period of peace: the consolidation of French influence in the satellite states would continue, while the British would certainly not be allowed their former commercial and diplomatic privileges in those areas; the French navy, dispersed in various ports, could be concentrated and rebuilt; and the economy could be rested before the next round of the struggle. In consequence of this, British opinion – which did not offer much criticism of the government at the conclusion of the Peace of Amiens (March 1802) – steadily swung in the other direction when it was observed that France was continuing the struggle by other means. British trade was denied entry into much of Europe. London was firmly told to keep out of Dutch, Swiss, and Italian matters. And French intrigues and aggressions were reported from Muscat to the West Indies and from Turkey to Piedmont. These reports, and the evidence of a large-scale French warship-building programme, caused the British government under Addington to refuse to hand back Malta and, in May 1803, to turn a cold war into a hot one.78

This final round of the seven major Anglo-French wars fought between 1689 and 1815 was to last twelve years, and was the most severely testing of them all. Just as before, each combatant had different strengths and weaknesses. Despite certain retrenchments in the fleet, the Royal Navy was in a very strong position when hostilities recommenced. While powerful squadrons blockaded the French coast, the overseas empires of France and its satellites were systematically recaptured. St Pierre et Miquelon, St Lucia, Tobago, and Dutch Guiana were taken before Trafalgar, and further advances were made in India; the Cape fell in 1806; Curaçao and the Danish West Indies in 1807; several of the Moluccas in 1808; Cayenne, French Guiana, San Domingo, Senegal, and Martinique in 1809; Guadeloupe, Mauritius, Amboina, and Banda in 1810; Java in 1811. Once again, this had no direct impact upon the European equilibrium, but it did buttress Britain’s dominance overseas and provide new ‘vents’ for exports denied their traditional access into Antwerp and Leghorn; and, even in its early stages, it prompted Napoleon to contemplate the invasion of southern England more seriously than ever before. With the Grand Army assembling before Boulogne and a grimly determined Pitt returned to office in 1804, each side looked forward to one final, decisive clash.

In actual fact, the naval and military campaigns of 1805 to 1808, despite containing several famous battles, revealed yet again the strategical constraints of the war. The French army was at least three times larger and much more experienced than its British equivalent, but command of the sea was required before it could safely land in England. Numerically, the French navy was considerable (about seventy ships of the line), a testimony to the resources which Napoleon could command; and it was reinforced by the Spanish navy (over twenty ships of the line) when that country entered the war late in 1804. However, the Franco-Spanish fleets were dispersed in half a dozen harbours, and their juncture could not be effected without running the risk of encountering a Royal Navy of vastly greater battle experience. The smashing defeat of those fleets at Trafalgar in October 1805 illustrated the ‘quality gap’ between the rival navies in the most devastating way. Yet if that dramatic victory secured the British Isles, it could not undermine Napoleon’s position on land. For this reason, Pitt had striven to tempt Russia and Austria into a third coalition, paying £1.75 million for every 100,000 men they could put into the field against the French. Even before Trafalgar, however, Napoleon had rushed his army from Boulogne to the upper Danube, annihilating the Austrians at Ulm, and then proceeded eastward to crush an Austro-Russian force of 85,000 men at Austerlitz in December. With a dispirited Vienna suing for peace for the third time, the French could once again assert control in the Italian peninsula and compel a hasty withdrawal of the Anglo-Russian forces there.79

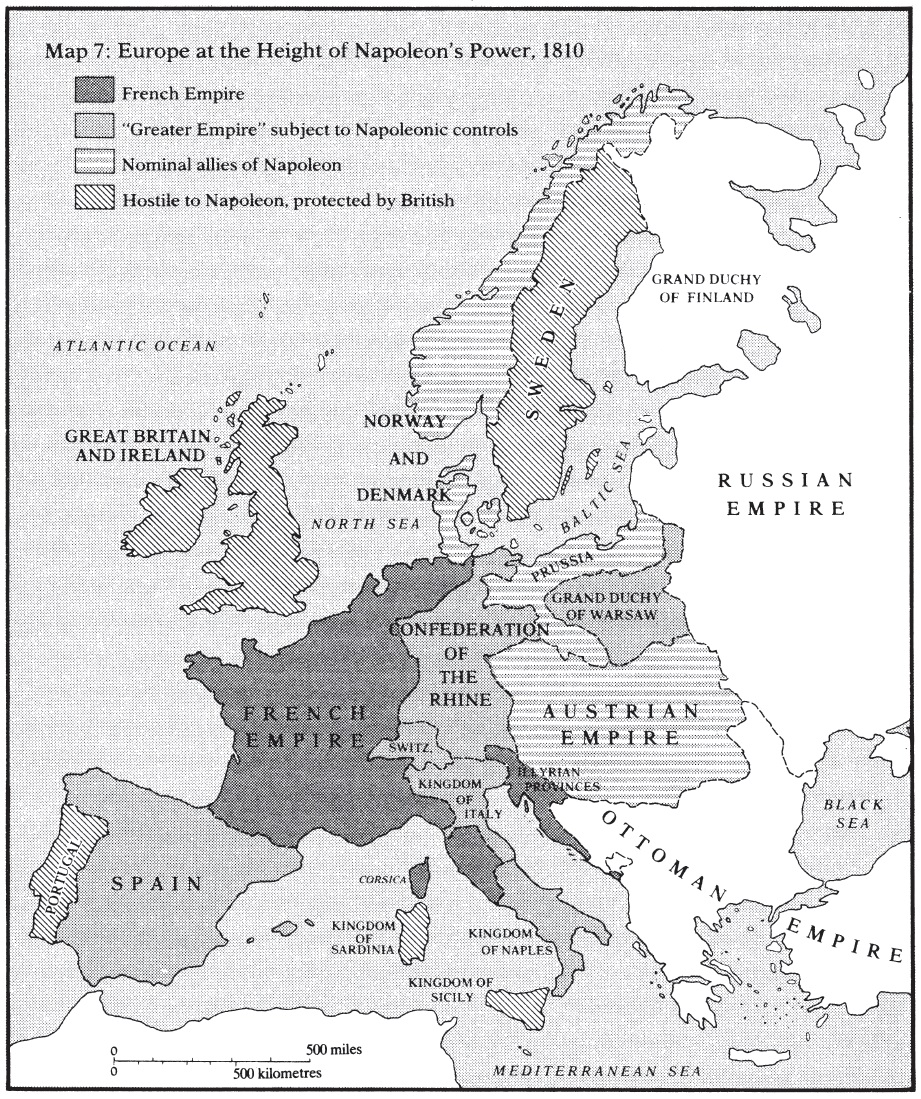

Whether or not the news of these great blows caused Pitt’s death in early 1806, they revealed once more the difficulty of bringing down a military genius like Napoleon. Indeed, the following years ushered in the zenith of French predominance in Europe. (See Map 7.) Prussia, whose earlier abstention had weakened the coalition, rashly declared war upon France in October 1806 and was crushed within the month. The large and stubborn Russian armies were an altogether different matter, but after several battles they, too, were badly hurt at the battle of Friedland (June 1807). At the peace treaties of Tilsit, Prussia was turned into a virtual satellite and Russia, while escaping lightly, agreed to ban British trade and promised eventually to join a French alliance. With southern and much of western Germany merged into the Confederation of the Rhine, with western Poland turned into the grand duchy of Warsaw, with Spain, Italy, and the Low Countries subservient, with the Holy Roman Empire at an end, there was no independent state – and no ally for the British – between Portugal and Sweden. This, in its turn, gave Napoleon his opportunity to ruin the ‘nation of shopkeepers’ in the most telling fashion: by banning their exports to Europe and hurting their economy, while accumulating for his own purposes the timber, masts, and other shipbuilding resources now denied to the Royal Navy. Indirectly, the British would be weakened before a further direct assault was mounted. Given Britain’s dependence upon European markets for its export industries and upon Baltic masts and Dalmatian oak for its fleet, the threat was immense. Finally, reduced earnings from exports would deny London the currency needed to pay subsidies to any allies and to purchase goods for its own expeditionary armies.

More than ever before, in this war, economic factors inter-meshed with strategy. At this central stage in the Anglo-French duel for supremacy, between Napoleon’s Berlin/Milan decrees banning trade with Britain (1806–7) and the French retreat from Moscow in 1812, the relative merits of the two opposing systems deserve further analysis. With each seeking to ruin the other economically, any significant weakness would sooner or later emerge – and have dire power-political consequences.

There is no doubt that Britain’s unusually large dependence upon foreign commerce by this time made it very vulnerable to the trading ban imposed under Napoleon’s ‘Continental System’.80 In 1808, and again in 1811–12, the commercial warfare waged by the French and their more compliant satellites (e.g. the Danes) was producing a crisis in British export trades. Vast stocks of manufactures were piled in warehouses, and the London docks were full to overflowing with colonial produce. Unemployment in the towns and unrest in the counties increased businessmen’s fears and caused many economists to call for peace; so, too, did the staggering rise in the national debt. When relations with the United States worsened and exports to that important market tumbled after 1811, the economic pressures seemed almost unbearable.

And yet, in fact, those pressures were borne, chiefly because they were never applied long or consistently enough to take full effect. The revolution in Spain against French hegemony eased the 1808 economic crisis in Britain, just as Russia’s break with Napoleon brought relief to the 1811–12 slump, allowing British goods to pour into the Baltic and northern Europe. Moreover, throughout the entire period large amounts of British manufactures and colonial re-exports were smuggled into the continent, at vast profits and usually with the connivance of bribed local officials; from Heligoland to Salonika, the banned produce travelled in circuitous ways to its eager customers – as it later travelled between Canada and New England during the Anglo-American War of 1812. Finally, the British export economy could also be sustained by the great rise in trade with regions untouched by the Continental System or the American ‘nonintercourse’ policy: Asia, Africa, the West Indies, Latin America (despite all the efforts of local Spanish governors), and the Near East. For all these reasons, and despite serious disruption to British trade in some markets for some of the time, the overall trend was clear: total exports of British produce rose from £21.7 million (1794–6) to £37.5 million (1804–6) to £44.4 million (1814–16).

The other main reason that the British economy did not crumble in the face of external pressures was that, unfortunately for Napoleon, it was now well into the Industrial Revolution. That these two major historical events interacted with each other in many singular ways is clear: government orders for armaments stimulated the iron, steel, coal, and timber trades, the enormous state spending (estimated at 29 per cent of gross national product) affected financial practices, and new export markets boosted production of some factories just as the French ‘counterblockade’ depressed it. Exactly how the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars affected the growth of the British economy as a whole is a complex and controversial topic, still being investigated by historians, many of whom now feel that the earlier notions of the swift pace of British industrialization in these decades are exaggerated. What is clear, however, is that the economy grew throughout this period. Pig-iron output, a mere 68,000 tons in 1788, had already soared to 244,000 tons in 1806 and rose further to 325,000 tons in 1811. Cotton, virtually a new industry before the war, expanded stupendously in the next two decades, absorbing ever more machinery, steam power, coal, and labour; by 1815, cotton goods had become Britain’s greatest export by far. A vast array of new docks and, inland, new canals, turnpikes, and iron rail tracks improved communications and stimulated further production. Regardless of whether this ‘boom’ would have been even greater without the military and naval struggle against France, the fact remains that British productivity and wealth were still rising fast – and could help to bear the burdens which Pitt and his successors imposed in order to pay for the war. Customs and excise receipts, for example, jumped from £13.5 million (1793) to £44.8 million (1815), while the yield from the new income and property taxes rose from £1.67 million in 1799 to £14.6 million in the final year of the war. In fact, between 1793 and 1815 the British government secured the staggering sum of £1.217 billion from direct and indirect taxes, and proceeded to raise a further £440 million in loans from the money markets without exhausting its credit – to the amazement of the more fiscally conservative Napoleon. In the critical final few years of the war, the government was borrowing more than £25 million annually, giving itself that decisive extra margin.81 To be sure, the British were taxed way beyond the limits conceived of by eighteenth-century bureaucrats, and the national debt almost trebled; but the new wealth made such burdens easier to bear – and permitted them, despite their smaller size and population, to endure the costs of war better than the imposing Napoleonic Empire.

The story of France’s economy between 1789 and 1815, and of its capacity to sustain large-scale war, is an even more complicated one for historians to unravel.82 The collapse of the ancien régime and the turmoil which followed undoubtedly caused a reduction in French economic activity for a while. On the other hand, the outpouring of public enthusiasm for the Revolution and the mobilization of national resources to meet foreign enemies led to a staggering increase in the output of cannon, small arms, and other military equipment, which in turn stimulated the iron and textile trades. In addition, some of the economic obstacles of the old order such as internal tariffs were swept away, and Napoleon’s own legal and administrative reforms aided the prospects for modernization. Even if the coming of the Consulate and the Empire led to the return of many of the features of the monarchical regime (e.g. reliance upon private bankers), this did not check a steady economic growth fuelled naturally by population increases, the stimulus of state spending, enhanced tariff protection, and the introduction of certain new technologies.

Nevertheless, there seems no doubt that the rate of growth in the French economy was much slower than in Britain’s. The most profound reason for this was that the agricultural sector, the largest by far, changed very little: for the replacement of the seigneur by his peasants was not, of itself, an agricultural revolution; and such widely proclaimed policies as the development of sugar beets (in substitution for British colonial cane sugar) had limited results. Poor communications meant that farmers were still tied to local markets, and little stimulus existed for radical innovations. This conservative frame of mind could also be seen in the nascent industrial sector, where new machinery and large-scale enterprises in, say, iron production were the exception rather than the rule. Significant advances were made, of course, but many of them were under the distorting influence of the war and the British naval blockade. Thus, the cotton industry benefited from the Continental System to the extent that it was protected from superior British competition (not to mention the competition from neutral or satellite states, whose goods were excluded by the high French tariffs); and it also benefited from the enhanced domestic market, since Napoleon’s conquests of bordering lands increased the number of ‘Frenchmen’ from 25 million in 1789 to 44 million in 1810. But this was offset by the shortage and high price of raw cotton, and by the slowdown in the introduction of new techniques from England. On the whole, French industry emerged from the war in a distinctly less competitive state because of this protection from foreign rivals.

The impact of the naval blockade increased this turning inward of the French economy.83 Its Atlantic sector, the fastest-growing in the eighteenth century and (as had been the case in Britain) potentially a key catalyst for industrialization, was increasingly cut off by the Royal Navy. The loss of Santo Domingo in particular was a heavy blow to French Atlantic trade. Other overseas colonies and investments were also lost and after 1806, even trade via neutral bottoms was halted. Bordeaux was dreadfully hurt. Nantes had its profitable French slave trade reduced to nothing. Even Marseilles, with alternative trading partners in the hinterland and northern Italy, saw its industrial output fall to one-quarter between 1789 and 1813. By contrast, regions in the north and east of France, such as Alsace, enjoyed the comparative security of land-based trade. Yet even if those areas, and people within them like wine-growers and cotton-spinners, profited in their protected environment, the overall impact upon the French economy was much less satisfactory. ‘Deindustrialized’ in its Atlantic sector, cut off from much of the outside world, it turned inward to its peasants, its small-town commerce, and its localized, uncompetitive, and relatively small-scale industries.

Given this economic conservatism – and, in some cases, definite evidence of retardation – the ability of the French to finance decades of Great Power war seems all the more remarkable.84 While the popular mobilization in the early to middle 1790s offers a ready reason, it cannot explain the Napoleonic era proper, when a long-service army of over 500,000 men (needing probably 150,000 new recruits each year) had to be paid for. Military expenditures, already costing at least 462 million francs in 1807, had soared to 817 million francs in 1813. Not surprisingly, the normal revenues could never manage to pay for such outlays. Direct taxes were unpopular at home and therefore could not be substantially raised – which chiefly explains Napoleon’s return to duties on tobacco, salt, and the other indirect taxes of the ancien régime; but neither they nor the various stamp duties and customs fees could prevent an annual deficit of hundreds of millions of francs. It is true that the creation of the Bank of France, together with a whole variety of other financial devices and institutions, allowed the state to conduct a disguised policy of paper money and thus to keep itself afloat on credit – despite the emperor’s proclaimed hostility to raising loans. Yet even that was not enough. The gap could only be filled elsewhere.

To a large if incalculable degree, in fact, Napoleonic imperialism was paid for by plunder. This process had begun internally, with the confiscation and sale of the property of the proclaimed ‘enemies of the Revolution’.85 When the military campaigns in defence of that revolution had carried the French armies into neighbouring lands, it seemed altogether natural that the foreigner should pay for it. War, to put it bluntly, would support war. By confiscation of crown and feudal properties in defeated countries; by spoils taken directly from the enemy’s armies, garrisons, museums, and treasuries; by imposing war indemnities in money or in kind; and by quartering French regiments upon satellite states and requiring the latter to supply contingents, Napoleon not only covered his enormous military expenditures, he actually produced considerable profits for France – and himself. The sums acquired by the administrators of this domaine extraordinaire in the period of France’s zenith were quite remarkable and in some ways foreshadow Nazi Germany’s plunder of its satellites and conquered foes during the Second World War. Prussia, for example, had to pay a penalty of 311 million francs after Jena, which was equal to half of the French government’s ordinary revenue. At each defeat, the Habsburg Empire was forced to cede territories and to pay a large indemnity. In Italy between 1805 and 1812 about half of the taxes raised went to the French. All this had the twin advantage of keeping much of the colossal French army outside the homeland, and of protecting the French taxpayer from the full costs of the war. Provided that army under its brilliant leader remained successful, the system seemed invulnerable. It was not surprising, therefore, to hear the emperor frequently asserting: