The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

The ‘Industrial Revolution’, most economic historians are at pains to stress, did not happen overnight. It was, compared with the political ‘revolutions’ of 1776, 1789, and 1917, a gradual, slow-moving process; it affected only certain manufactures and certain means of production; and it occurred region by region, rather than involving an entire country.1 Yet all these caveats cannot avoid the fact that a fundamentally important transformation in man’s economic circumstances began to occur sometime around 1780 – not less significant, in the view of one authority, than the (admittedly far slower) transformation of savage Palaeolithic hunting man to domesticated Neolithic farming man.2 What industrialization, and in particular the steam engine, did was to substitute inanimate for animate sources of power; by converting heat into work through the use of machines – ‘rapid, regular, precise, tireless’ machines3 – mankind was thus able to exploit vast new sources of energy. The consequences of introducing this novel machinery were simply stupendous: by the 1820s someone operating several power-driven looms could produce twenty times the output of a hand worker, while the power-driven ‘mule’ (or spinning machine) had two hundred times the capacity of a spinning wheel. A single railway engine could transport goods which would have required hundreds of packhorses, and do it far more quickly. To be sure, there were many other important aspects to the Industrial Revolution – the factory system, for example, or the division of labour. But the vital point for our purposes was the massive increase in productivity, especially in the textile industries, which in turn stimulated a demand for more machines, more raw materials (above all, cotton), more iron, more shipping, better communications, and so on.

Moreover, as Professor Landes has observed, this unprecedented increase in man’s productivity was self-sustaining:

Where previously an amelioration of the conditions of existence, hence of survival, and an increase in economic opportunity had always been followed by a rise in population that eventually consumed the gains achieved, now for the first time in history, both the economy and the knowledge were growing fast enough to generate a continuing flow of investment and technological innovation, a flow that lifted beyond visible limits the ceiling of Malthus’s positive checks.4

The latter remark is also vitally important. From the eighteenth century onward, the growth in world population had begun to accelerate: Europe’s numbers rose from 140 million in 1750 to 187 million in 1800 to 266 million in 1850; Asia’s exploded from over 400 million in 1750 to around 700 million a century later.5 Whatever the reasons – better climatic conditions, improved fecundity, decline in diseases – increases of that size were alarming; and although agricultural output both in Europe and Asia also expanded in the eighteenth century and was in fact another general reason for the rise in population, the sheer number of new heads (and stomachs) threatened over time to cancel out the benefits of all such additions in agricultural output. Pressure upon marginal lands, rural unemployment, and a vast drift of families into the already overcrowded cities of Europe in the late eighteenth century were but some of the symptoms of this population surge.6

What the Industrial Revolution in Britain did (in very crude macroeconomic terms) was to so increase productivity on a sustained basis that the consequent expansion both in national wealth and in the population’s purchasing power constantly outweighed the rise in numbers. While the country’s population rose from 10.5 million in 1801 to 41.8 million in 1911 – an annual increase of 1.26 per cent – its national product rose much faster, perhaps as much as fourteenfold over the nineteenth century. Depending upon the area covered by the statistics,* there was an annual average rise in gross national product of between 2 and 2.25 per cent. In Queen Victoria’s reign alone, product per capita rose two and a half times.

Compared with the growth rates achieved by many nations after 1945, these were not spectacular figures. It was also true, as social historians remind us, that the Industrial Revolution inflicted awful costs upon the new proletariat which laboured in the factories and mines and lived in the unhealthy, crowded, jerry-built cities. Yet the fundamental point remains that the sustained increases in productivity of the Machine Age brought widespread benefits over time: average real wages in Britain rose between 15 and 25 per cent in the years 1815–50, and by an impressive 80 per cent in the next half-century. ‘The central problem of the age’, Ashton has reminded those critics who believe that industrialization was a disaster, ‘was how to feed and clothe and employ generations of children outnumbering by far those of any earlier time.’7 The new machines not only employed an increasingly large share of the burgeoning population, but also boosted the nation’s overall per capita income; and the rising demand of urban workers for foodstuffs and essential goods was soon to be met by a steam-driven communications revolution, with railways and steamships bringing the agricultural surpluses of the New World to satisfy the requirements of the Old.

We can grasp this point in a different way by using Professor Landes’s calculations. In 1870, he notes, the United Kingdom was using 100 million tons of coal, which was ‘equivalent to 800 million million Calories of energy, enough to feed a population of 850 million adult males for a year (actual population was then about 31 million)’. Again, the capacity of Britain’s steam engines in 1870, some 4 million horsepower, was equivalent to the power which could be generated by 40 million men; but ‘this many men would have eaten some 320 million bushels of wheat a year – more than three times the annual output of the entire United Kingdom in 1867–71’.8 The use of inanimate sources of power allowed industrial man to transcend the limitations of biology and to create spectacular increases in production and wealth without succumbing to the weight of a fast-growing population. By contrast, Ashton soberly noted (as late as 1947):

There are today on the plains of India and China men and women, plague-ridden and hungry, living lives little better, to outward appearance, than those of the cattle that toil with them by day and share their places of sleep by night. Such Asiatic standards, and such unmechanized horrors, are the lot of those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution.9

The Eclipse of the Non-European World

Before discussing the effects of the Industrial Revolution upon the Great Power system, it will be as well to understand its impact farther afield, especially upon China, India, and other non-European societies. The losses they suffered were twofold, both relative and absolute. It was not the case, as was once fancied, that the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America lived a happy, ideal existence prior to the impact of western man. ‘The elemental truth must be stressed that the characteristic of any country before its industrial revolution and modernization is poverty … with low productivity, low output per head, in traditional agriculture, any economy which has agriculture as the main constituent of its national income does not produce much of a surplus above the immediate requirements of consumption …’10 On the other hand, in view of the fact that in 1800 agricultural production formed the basis of both European and non-European societies, and of the further fact that in countries such as India and China there also existed many traders, textile producers, and craftsmen, the differences in per capita income were not enormous; an Indian handloom weaver, for example, may have earned perhaps as much as half of his European equivalent prior to industrialization. What this also meant was that, given the sheer numbers of Asiatic peasants and craftsmen, Asia still contained a far larger share of world manufacturing output* than did the much less populous Europe before the steam engine and the power loom transformed the world’s balances.

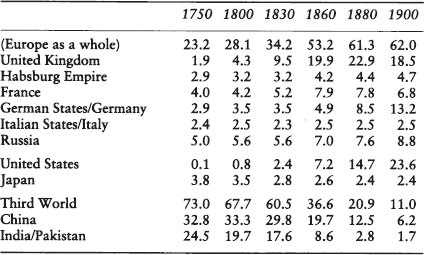

Just how dramatically those balances shifted in consequence of European industrialization and expansion can be seen in Bairoch’s two ingenious calculations (see Tables 6–7).11

TABLE 6. Relative Shares of World Manufacturing Output, 1750–1900

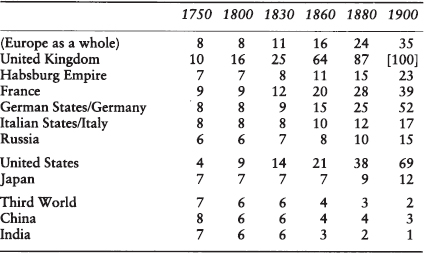

TABLE 7. Per Capita Levels of Industrialization, 1750–1900

(relative to UK in 1900 = 100)

The root cause of these transformations, it is clear, lay in the staggering increases in productivity emanating from the Industrial Revolution. Between, say, the 1750s and the 1830s the mechanization of spinning in Britain had increased productivity in that sector alone by a factor of 300 to 400, so it is not surprising that the British share of total world manufacturing rose dramatically – and continued to rise as it turned itself into the ‘first industrial nation’.12 When other European states and the United States followed the path to industrialization, their shares also rose steadily, as did their per capita levels of industrialization and their national wealth. But the story for China and India was quite a different one. Not only did their shares of total world manufacturing shrink relatively, simply because the West’s output was rising so swiftly; but in some cases their economies declined absolutely, that is, they de-industrialized, because of the penetration of their traditional markets by the far cheaper and better products of the Lancashire textile factories. After 1813 (when the East India Company’s trade monopoly ended), imports of cotton fabrics into India rose spectacularly, from 1 million yards (1814) to 51 million (1830) to 995 million (1870), driving out many of the traditional domestic producers in the process. Finally – and this returns us to Ashton’s point about the grinding poverty of ‘those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution’ – the large rise in the populations of China, India, and other Third World countries probably reduced their general per capita income from one generation to the next. Hence Bairoch’s remarkable – and horrifying – suggestion that whereas the per capita levels of industrialization in Europe and the Third World may have been not too far apart from each other in 1750, the latter’s was only one-eighteenth of the former’s (2 per cent to 35 per cent) by 1900, and only one-fiftieth of the United Kingdom’s (2 per cent to 100 per cent).

The ‘impact of western man’ was, in all sorts of ways, one of the most noticeable aspects of the dynamics of world power in the nineteenth century. It manifested itself not only in a variety of economic relationships – ranging from the ‘informal influence’ of coastal traders, shippers, and consuls to the more direct controls of planters, railway builders, and mining companies13 – but also in the penetrations of explorers, adventurers, and missionaries, in the introduction of western diseases, and in the proselytization of western faiths. It occurred as much in the centres of continents – westward from the Missouri, southward from the Aral Sea – as it did up the mouths of African rivers and around the coasts of Pacific archipelagoes. If it eventually had its impressive monuments in the roads, railway networks, telegraphs, harbours, and civic buildings which (for example) the British created in India, its more horrific side was the bloodshed, rapine, and plunder which attended so many of the colonial wars of the period.14 To be sure, the same traits of force and conquest had existed since the days of Cortez, but now the pace was accelerating. In the year 1800, Europeans occupied or controlled 35 per cent of the land surface of the world; by 1878 this figure had risen to 67 per cent, and by 1914 to over 84 per cent.15

The advanced technology of steam engines and machine-made tools gave Europe decisive economic and military advantages. The improvements in the muzzle-loading gun (percussion caps, rifling, etc.) were ominous enough; the coming of the breechloader, vastly increasing the rate of fire, was an even greater advance; and the Gatling guns, Maxims, and light field artillery put the final touches to a new ‘firepower revolution’ which quite eradicated the chances of a successful resistance by indigenous peoples reliant upon older weaponry. Furthermore, the steam-driven gunboat meant that European seapower, already supreme in open waters, could be extended inland, via major waterways like the Niger, the Indus, and the Yangtze: thus the mobility and firepower of the ironclad Nemesis during the Opium War actions of 1841 and 1842 was a disaster for the defending Chinese forces, which were easily brushed aside.16 It was true, of course, that physically difficult terrain (e.g. Afghanistan) blunted the drives of western military imperialism, and that among non-European forces which adopted the newer weapons and tactics – like the Sikhs and the Algerians in the 1840s – the resistance was far greater. But whenever the struggle took place in open country where the West could deploy its machine guns and heavier weapons, the issue was never in doubt. Perhaps the greatest disparity of all was seen at the very end of the century, during the battle of Omdurman (1898), when in one half-morning the Maxims and Lee-Enfield rifles of Kitchener’s army destroyed 11,000 Dervishes for the loss of only forty-eight of their own troops. In consequence, the firepower gap, like that which had opened up in industrial productivity, meant that the leading nations possessed resources fifty or a hundred times greater than those at the bottom. The global dominance of the West, implicit since da Gama’s day, now knew few limits.

Britain as Hegemon?

If the Punjabis and Annamese and Sioux and Bantu were the ‘losers’ (to use Eric Hobsbawm’s term)17 in this early-nineteenth-century expansion, the British were undoubtedly the ‘winners’. As noted in the previous chapter, they had already achieved a remarkable degree of global pre-eminence by 1815, thanks to their adroit combination of naval mastery, financial credit, commercial expertise, and alliance diplomacy. What the Industrial Revolution did was to enhance the position of a country already made supremely successful in the preindustrial, mercantilist struggles of the eighteenth century, and then to transform it into a different sort of power. If (to repeat) the pace of change was gradual rather than revolutionary, the results were nonetheless highly impressive. Between 1760 and 1830, the United Kingdom was responsible for around ‘two-thirds of Europe’s industrial growth of output’,18 and its share of world manufacturing production leaped from 1.9 to 9.5 per cent; in the next thirty years, British industrial expansion pushed that figure to 19.9 per cent, despite the spread of the new technology to other countries in the West. Around 1860, which was probably when the country reached its zenith in relative terms, the United Kingdom produced 53 per cent of the world’s iron and 50 per cent of its coal and lignite, and consumed just under half of the raw cotton output of the globe. ‘With 2 per cent of the world’s population and 10 per cent of Europe’s, the United Kingdom would seem to have had a capacity in modern industries equal to 40–45 per cent of the world’s potential and 55–60 per cent of that in Europe.’19 Its energy consumption from modern sources (coal, lignite, oil) in 1860 was five times that of either the United States or Prussia/Germany, six times that of France, and 155 times that of Russia! It alone was responsible for one-fifth of the world’s commerce, but for two-fifths of the trade in manufactured goods. Over one-third of the world’s merchant marine flew under the British flag, and that share was steadily increasing. It was no surprise that the mid-Victorians exulted at their unique state being now (as the economist Jevons put it in 1865) the trading centre of the universe:

The plains of North America and Russia are our corn fields; Chicago and Odessa our granaries; Canada and the Baltic are our timber forests; Australasia contains our sheep farms, and in Argentina and on the western prairies of North America are our herds of oxen; Peru sends her silver, and the gold of South Africa and Australia flows to London; the Hindus and the Chinese grow tea for us, and our coffee, sugar and spice plantations are in all the Indies. Spain and France are our vineyards and the Mediterranean our fruit garden; and our cotton grounds, which for long have occupied the Southern United States, are now being extended everywhere in the warm regions of the earth.20

Since such manifestations of self-confidence, and the industrial and commercial statistics upon which they rested, seemed to suggest a position of unequalled dominance on Britain’s part, it is fair to make several other points which put this all in a better context. First – although it is a somewhat pedantic matter – it is unlikely that the country’s gross national product (GNP) was ever the largest in the world during the decades following 1815. Given the sheer size of China’s population (and, later, Russia’s) and the obvious fact that agricultural production and distribution formed the basis of national wealth everywhere, even in Britain prior to 1850, the latter’s overall GNP never looked as impressive as its per capita product or its stage of industrialization. Still, ‘by itself the volume of total GNP has no important significance’;21 the physical product of hundreds of millions of peasants may dwarf that of five million factory workers, but since most of it is immediately consumed, it is far less likely to lead to surplus wealth or decisive military striking power. Where Britain was strong, indeed unchallenged, in 1850 was in modern, wealth-producing industry, with all the benefits which flowed from it.

On the other hand – and this second point is not a pedantic one – Britain’s growing industrial muscle was not organized in the post-1815 decades to give the state swift access to military hardware and manpower as, say, Wallenstein’s domains did in the 1630s or the Nazi economy was to do. On the contrary, the ideology of laissez-faire political economy, which flourished alongside this early industrialization, preached the causes of eternal peace, low government expenditures (especially on defence), and the reduction of state controls over the economy and the individual. It might be necessary, Adam Smith had conceded in The Wealth of Nations (1776), to tolerate the upkeep of an army and a navy in order to protect British society ‘from the violence and invasion of other independent societies’; but since armed forces per se were ‘unproductive’ and did not add value to the national wealth in the way that a factory or a farm did, they ought to be reduced to the lowest possible level commensurate with national safety.22 Assuming (or, at least, hoping) that war was a last resort, and ever less likely to occur in the future, the disciples of Smith and even more of Richard Cobden would have been appalled at the idea of organizing the state for war. As a consequence, the ‘modernization’ which occurred in British industry and communications was not paralleled by improvements in the army, which (with some exceptions)23 stagnated in the post-1815 decades.

However pre-eminent the British economy in the mid-Victorian period, therefore, it was probably less ‘mobilized’ for conflict than at any time since the early Stuarts. Mercantilist measures, with their emphasis upon the links between national security and national wealth, were steadily eliminated: protective tariffs were abolished; the ban on the export of advanced technology (e.g. textile machinery) was lifted; the Navigation Acts, designed among other things to preserve a large stock of British merchant ships and seamen for the event of war, were repealed; imperial ‘preferences’ were ended. By contrast, defence expenditures were held to an absolute minimum, averaging around £15 million a year in the 1840s and not above £27 million in the more troubled 1860s; yet in the latter period Britain’s GNP totalled about £1 billion. Indeed, for fifty years and more following 1815 the armed services consumed only about 2–3 per cent of GNP, and central government expenditures as a whole took much less than 10 per cent – proportions which were far less than in either the eighteenth or the twentieth century.24 These would have been impressively low figures for a country of modest means and ambitions. For a state which managed to ‘rule the waves’, which possessed an enormous, far-flung empire, and which still claimed a large interest in preserving the European balance of power, they were truly remarkable.

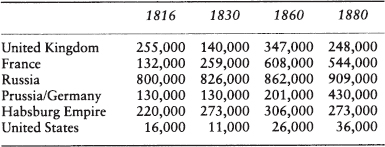

Like that of the United States in, say, the early 1920s, therefore, the size of the British economy in the world was not reflected in the country’s fighting power; nor could its laissez-faire institutional structures, with a minuscule bureaucracy increasingly divorced from trade and industry, have been able to mobilize British resources for an all-out war without a great upheaval. As we shall see below, even the more limited Crimean War shook the system severely, yet the concern which that exposure aroused soon faded away. Not only did the mid-Victorians show ever less enthusiasm for military interventions in Europe, which would always be expensive, and perhaps immoral, but they reasoned that the equilibrium between the continental Great Powers which generally prevailed during the six decades after 1815 made any full-scale commitment on Britain’s part unnecessary. While it did strive, through diplomacy and the movement of naval squadrons, to influence political events along the vital peripheries of Europe (Portugal, Belgium, the Dardanelles), it tended to abstain from intervention elsewhere. By the late 1850s and early 1860s, even the Crimean campaign was widely regarded as a mistake. Because of this lack of inclination and effectiveness, Britain did not play a major role in the fate of Piedmont in the critical year of 1859, it disapproved of Palmerston and Russell’s ‘meddling’ in the Schleswig-Holstein affair of 1864, and it watched from the sidelines when Prussia defeated Austria in 1866 and France four years later. It is not surprising to see that Britain’s military capacity was reflected in the relatively modest size of its army during this period (see Table 8), little of which could, in any case, be mobilized for a European theatre.

TABLE 8. Military Personnel of the Powers, 1816–80 25

Even in the extra-European world, where Britain preferred to deploy its regiments, military and political officials in places such as India were almost always complaining of the inadequacy of the forces they commanded, given the sheer magnitude of the territories they controlled. However imposing the empire may have appeared on a world map, district officers knew that it was being run on a shoestring. But all this is merely saying that Britain was a different sort of Great Power by the early to middle nineteenth century, and that its influence could not be measured by the traditional criteria of military hegemony. Where it was strong was in certain other realms, each of which was regarded by the British as far more valuable than a large and expensive standing army.

The first of these was in the naval realm. For over a century before 1815, of course, the Royal Navy had usually been the largest in the world. But that maritime mastery had frequently been contested, especially by the Bourbon powers. The salient feature of the eighty years which followed Trafalgar was that no other country, or combination of countries, seriously challenged Britain’s control of the seas. There was, it is true, the occasional French ‘scare’; and the Admiralty also kept a wary eye upon Russian shipbuilding programmes and upon the American construction of large frigates. But each of those perceived challenges faded swiftly, leaving British sea power to exercise (in Professor Lloyd’s words) ‘a wider influence than has ever been seen in the history of maritime empires’.26 Despite a steady reduction in its own numbers after 1815, the Royal Navy was at some times probably as powerful as the next three or four navies in actual fighting power. And its major fleets were a factor in European politics, at least on the periphery. The squadron anchored in the Tagus to protect the Portuguese monarchy against internal or external dangers; the decisive use of naval force in the Mediterranean (against the Algiers pirates in 1816; smashing the Turkish fleet at Navarino in 1827; checking Mehemet Ali at Acre in 1840); and the calculated dispatch of the fleet to anchor before the Dardanelles whenever the ‘Eastern Question’ became acute; these were manifestations of British sea power which, although geographically restricted, nonetheless weighed in the minds of European governments. Outside Europe, where smaller Royal Navy fleets or even individual warships engaged in a whole host of activities – suppressing piracy, intercepting slaving ships, landing marines, and overawing local potentates from Canton to Zanzibar – the impact seemed perhaps even more decisive.27