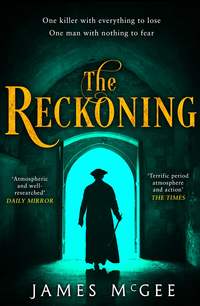

The Reckoning

The smile was replaced suddenly by a more thoughtful expression. “I hope you catch him.” There was the merest pause then Locke said, “When you do run him down, it will be interesting to see if he also tries to resist arrest.”

Before Hawkwood could respond, the apothecary gave a quick, wry smile, nodded and turned for his desk, his hands clasped behind his back.

The attendant moved aside to allow Hawkwood to exit. It was as the door was closing behind him that the thought struck. Sticking out a hand to stop the door’s swing, he stepped back into the room. Locke was back behind his desk. He glanced up.

“There is one thing,” Hawkwood said.

Locke half rose.

“Something I forgot to ask.”

The apothecary nodded sombrely. “I know.”

“You know?”

Locke lowered himself into his chair. “It’s just occurred to you that the question you should have asked is not: will he kill again? The question is: has he killed before?”

“Yes.”

“Because if you are to prevent him from committing a similar crime, it is not the future you should concentrate upon, but the past. If you can establish a truth using that method, then you will have your point of reference from which everything else will stem.”

“So?” Hawkwood said. “In your opinion, could he have done this before?”

Gazing back at him, Locke removed his spectacles and the handkerchief from his sleeve and began to clean each lens with slow, circular motions. After several seconds of concentrated thought, he put away the handkerchief, placed the spectacles back on the bridge of his nose, and stared at Hawkwood.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “Almost certainly.”

6

“That’s it?” Jago said, unable to hide his disbelief. “You want to know if any working girls have gone missing? You’re bloody joking, right? Know how many there are in this city? Bloody ’undreds – hell, thousands, more like. And you want to track down one of them?”

“I don’t need to track her down. I know where she is. She’s on a slab in a dead house; what’s left of her. What I don’t know is her name. I’m hoping it’s Rose.”

“Because of a tattoo? Jesus, that’s a bloody long shot.”

“You may be right. Most likely you are right, but that doesn’t mean I have to send her to Cross Bones to be tipped into another bloody ditch.”

Jago frowned. “So, what the hell makes this one so special? Bawds and pimps beat their molls all the time. Kill ’em too, when they’re in the mood.”

“Not like this,” Hawkwood said.

Jago sat back. “That bad?”

“Worse.”

Hawkwood described the scene in Quill’s dead house.

Jago remained silent throughout the telling. He winced at the mention of the carved wounds. “Jesus,” he muttered finally.

“Quill asked me the same question,” Hawkwood said.

“What? Oh, you mean, why this one?”

Hawkwood nodded. “I told him it was because one of John Moore’s veterans didn’t think it right that someone tossed her into a hole without due ceremony and I didn’t want the bloody resurrection men getting to her.”

“Sounds good enough to me,” Jago said.

“There is another reason,” Hawkwood said.

“Which is?”

“The bastards who put her there thought they could get away with it. They’re mistaken.”

Jago sighed and sat back. He stared into his drink and then looked up. “You want me to ask Connie if she’s heard anything.”

Hawkwood nodded.

“You do know the old one about needles and haystacks, right?”

“You’re all I’ve got,” Hawkwood said.

Jago gave a wry smile. “Now, where’ve I heard that before? All right, I’ll ’ave a word. But I wouldn’t get your hopes up. It’s likely you’ll never know who she was. She’ll be just another nameless lass set for a pauper’s grave.”

“She’s somebody’s daughter.”

“Who you think might be a moll, which means there’s a good chance she’s either been disowned or discarded.”

“Even so,” Hawkwood said.

After a second’s lapse, Jago acknowledged Hawkwood’s response with an understanding nod. “Aye, even so.”

Jago lay with his arm around Connie Fletcher’s shoulder. Her head rested on his chest, her ash-blonde hair loose about her face.

“Need to ask you something,” Jago said.

“You want to go around again?” Connie chuckled throatily as she ran her lips across the still raw wounds in his shoulder. “I’ll be gentle.”

Jago gasped as her hand began to slide south beneath the bedcover. “Bloody hell, woman, give us a chance. I ain’t caught my breath from last time.”

Connie removed her hand with an exaggerated sigh and snuggled closer. “All right, what then?”

At the angle they were lying, Jago couldn’t see Connie’s face, but he sensed she was still smiling. It made him wonder if she was expecting the question, the one that tended to end up with a ring and the services of a vicar. He felt a twinge of guilt. He’d been with Connie longer than he’d been with any woman, but marriage? Not that the thought hadn’t crossed his mind. Connie’s too, he suspected, even though they’d never discussed the possibility. He waited until his pulse had settled down and then said, “There’s been a killing. Captain’s investigating. He reckons she might have been a workin’ girl.”

Connie lifted her head. “Why’s that?”

“She was young, she weren’t dressed in rags and she has – had – a tattoo.”

The bedcover slid away as Connie sat up. “That’s his definition of a working girl? Someone who’s young, dresses decent and has a tattoo? He needs to get out more.”

“How many ladies you know have tattoos?” Jago asked.

“Can’t say as I know that many ladies,” Connie said deftly. Then she frowned. “Hang on. What about my tattoo? What’s that make me?”

Jago gazed back at her. “You don’t have a tattoo.”

Connie raised one eyebrow. “Might have.”

“No,” Jago said. “I’d have found it. Trust me.”

“Just checking,” Connie said, patting his chest. “But it proves that not every working girl has one.”

Jago pulled his head back to look at her. “You still see yourself as a workin’ girl?”

“Well as sure as God made little green apples, I’m no lady.”

“You’re my lady,” Jago said.

Connie smiled. “Good answer, but I was a working girl, before I went into management, which doesn’t say much for your theory, now, does it?”

“All right, point taken. But like I said, it weren’t my theory.”

“Which means it’s just as likely there are proper ladies out there who do have tattoos.”

Jago realized he’d been outsmarted. Connie’s still-arched eyebrow and her naked breasts swaying enticingly in front of his nose weren’t helping.

“What kind of tattoo?” she asked, after a considered pause.

“A rose.” Jago tapped Connie’s upper right arm. “On her shoulder. Told him the chances were slim to none, but the captain thinks it could be her name.”

Connie went quiet.

“What?” Jago said.

She stared at him, her face suddenly serious. “You’re sure it was a rose?”

Jago frowned. “I’m pretty sure the captain knows what a rose looks like. Why? You saying you might’ve known her?”

“I’m saying if her name was Rose, it’s more likely it was a coincidence.”

Jago sat up. “Sorry, girl, you’ve lost me.”

Connie shook her head. Her eyes held his. “A rose tattoo doesn’t have to mean it’s her name. Chances are it was an owner’s mark.”

“Come again?”

Connie didn’t reply but waited for the penny to drop.

“She was branded,” Jago said.

“It’s why some people call them stables.” Anger flared briefly in Connie’s eyes.

“So who owns this one?”

“Those of us in the know call her the Widow.”

Jago grimaced. “Cheery. I can see how that’d draw the customers in.”

Connie’s mouth moved, but if it was meant as a smile, there was no humour in it.

“Well, she doesn’t call herself that. Her real name’s Ellie Pearce. Doesn’t like to be called that either, though. These days, she goes by Lady Eleanor Rain.”

“Does she now? Well, I suppose it’s a tad more swish than Lady Ellie. So, what’s her story? She got a tattoo?”

Connie ignored the quip. “Supposedly started out with her ma. The old girl ran a business over in Half Moon Alley.”

“You mean it was a knocking shop. Nothin’ like keeping it in the family.”

“Well, she might have turned a trick or two in her younger days, but Ma Pearce was more purveyor than prossie.”

“What’d she purvey?”

“Perfumes, powders and oils, machines – you name it.”

“Machines?” Jago said, startled. “What sort of machines?”

Connie gazed back at him despairingly, dropped her eyes towards his crotch and then rewarded him with a look.

“Ah, right, understood; that sort. Bloody glad you and me don’t bother; all that fiddling around. Mood’s bloody gone by the time you’ve tied the damned thing on. Talk about a passion killer. Sorry, you were sayin’?”

“Word was that her mother used to pimp Ellie out to help pay the rent when business was slack.”

“Wouldn’t’ve thought that kind of business was ever slack,” Jago murmured, earning himself another reproving look.

“It happens. Anyway, supposedly, she took to it like a duck to water; went independent and started charging from a room above the Rose Inn over on Chick Lane.”

“Nice neighbourhood.”

“Nice for her. Made enough she was able to persuade the landlord to rent her a couple more rooms round the back. Started out with three molls, I think it was. That close to Smithfield, they weren’t short of customers.”

Customers who weren’t particular about their surroundings, Jago thought. On market days, the gutters in the adjacent lanes ran red with the blood and offal that seeped out of the nearby slaughterhouses.

“Wasn’t long before she’d earned enough to move to better premises. I don’t recall where; Holborn, maybe. That’s when she branched out. Found herself a rich patron – Sir Nicholas Rain. Bedded and wedded the poor bugger, wore him out; inherited when he died – hence the new name – and used the legacy to expand her business. I heard most of her early clients were swells she’d met through her husband: gentlemen of the nobility and so forth. Never looked back since.”

A retort hovered on Jago’s lips but was quelled when Connie continued, “Likes to dress her girls in the latest fashions. Her promise is they’ll satisfy all desires – and I do mean all. Her speciality’s organizing tableaux. I heard the Rites of Venus is one. She’ll arrange for half a dozen virgins to lose their cherries in front of an audience. When that’s over, the spectators are allowed to join in; so long as they pay, of course.”

“Of course,” Jago said drily.

“Earned herself a fortune, by all accounts; bragged it’d take a working man a hundred years to earn what she’s managed to put away for her rainy day.”

“She sounds … enterprisin’. And all her girls carry the brand?”

Connie nodded. “A rose. That way, anyone trying to muscle in knows they’re already spoken for.”

“Any idea where she’s set up her stall now?”

“Last I heard, she has a fine townhouse up near Portman Square.”

“Nice,” Jago said. “That way she gets the majors and the marquesses.”

Portman Square lay to the west, to the north of Oxford Street, within an area containing some of the largest private houses in London. It was also close to Portman Barracks, one of the many London barracks used in rotation by an assortment of cavalry and infantry regiments, among them the Foot Guards who were responsible for protecting the Royal Family.

“Calls it the Salon. Landed on her feet, did our Ellie.”

“As opposed to her back, you mean. Don’t like her much, do you?”

Connie made a face. “Don’t know her well enough to make that judgement. Can’t fault her ambition, though; she came up the hard way – yes, you can smile – saw an opportunity and took it. If I was honest, we’re probably a lot alike, though neither of us’d care to admit it.”

“Reckon you just did,” Jago said. “Well, I ain’t sure how much that’ll help, but I’ll pass it on; give the captain the heads-up.”

“Yes, well, when you do, you tell him to tread softly. Our Ellie has influential friends.”

“Can’t say as that’ll stop him askin’ awkward questions,” Jago said doubtfully.

“No,” Connie conceded. “I don’t suppose it will.”

“Want me to go with you?” Jago asked.

“To a knocking shop?”

“Don’t think they call it that. Connie tells me it’s a salon.”

“It’s still a knocking shop,” Hawkwood said. “Calling it a salon just means it’s got carpets on the floor instead of sawdust.”

“You want me to tag along or don’t you? Guard your back?”

“It’s not my back I’ll be worried about. No, I appreciate the offer, but I think I’ll cope. How’s the shoulder, by the way?”

“Hurts when I laugh.” Jago grinned.

They were seated at the window table on the first floor of the Hanged Man. Both men had their backs to the newly replaced glass with the table between them and the room.

“In case we ’as to hide behind it,” Jago had quipped when they’d sat down.

Hawkwood doubted lightning would strike twice in the same place in the space of a few days, but as it was Jago’s home patch he wasn’t going to argue with the former sergeant’s logic. There was no sign of Jasper, Del or Ned, but Micah was there, seated at the table at the top of the stairs, and Hawkwood had to admit to himself that the young man’s quiet presence was surprisingly reassuring.

“Any more Shaughnessys turn up?” he asked.

Jago took a sip from his mug and shook his head. “They have not. I’ve put the word out, but nothing’s come back. With luck, if there were any hangin’ round, they’ve buggered off back to the bogs. Still keepin’ my eyes open, though. Can’t be too careful and I did suggest that if Del or any of the others wanted to take a leak, they should piss in pairs just in case.”

Jago grinned as he topped up Hawkwood’s mug from the bottle by his elbow. “Connie said the Widow knows people and I should warn you to watch your step.”

“Don’t I always?”

Jago snorted. “You expect me to answer that?”

Hawkwood smiled thinly.

“Suit yourself,’ Jago said. “But if I were you, I wouldn’t go talking to any strange women.”

“In case you’ve forgotten, that’s the sole purpose of my visit.”

Jago winked and took a sip from his glass.

“By the way,” Hawkwood said, “in all that excitement, I forgot to ask: did you and Connie ever buy yourselves that carriage?”

“Carriage?” Jago blinked at the sudden change of subject.

“I’ll take that as a no, then. What happened? Before I went away, you were thinking of buying a horse and gig so that you and Connie could ride around Hyde Park and mix with the swells.”

“Ah, that.” Jago stared at him. “Remind me again; how long is it you’ve been gone?”

“Three months.”

“Well, that explains it.”

“You mean there was a change of plan?”

“Not certain there ever was a plan, as such; more like a bloody stupid idea.” The former sergeant smiled ruefully. “Be honest, can you see me and Connie swannin’ round the park in a carriage?”

“Connie, maybe,” Hawkwood said. “Not you.”

“I’ll tell her you said that, she’ll be tickled pink.” Jago frowned. “What made you think about Connie and carriages?”

Hawkwood did not reply.

“What, you getting maudlin in your old age?” Jago asked. Then his chin lifted. “Ah, don’t tell me; you and Maddie had words? Is that it?” Jago nodded to himself as if everything had suddenly been made clear, then tilted his head enquiringly. “What’d she say when you got back?”

“Not a hell of a lot,” Hawkwood said.

Maddie was Maddie Teague, landlady of the Blackbird tavern. Three months before, when Hawkwood had been preparing to leave for France with no expectation of an imminent return, Maddie had asked him if she should keep his room. Her green eyes had transfixed him when she’d posed the question. She’d tried to make light of her enquiry, telling him it had been made in jest, but he’d read the concern in her face and her genuine fear for his safety.

Hawkwood had smiled and told her that she should keep the room, but they’d both known there was no guarantee that he’d make it back. Despite that, there had been no whispered endearments, no lingering embrace. Instead, Maddie had stepped close and tapped his chest with her closed fist before resting her palm across his cheek. She had then asked him how long she should wait for news.

“You’ll know,” Hawkwood had told her.

“Then don’t expect me to cry myself to sleep,” she’d retorted, but she had not been able to hide the catch in her voice.

It had been a cold and damp morning when the mail coach deposited Hawkwood at the Saracen’s Head in Snow Hill. The 270-mile journey from Falmouth had taken four days. If he’d travelled by regular means it would have taken a week. It was the same route by which the news of Nelson’s death at Trafalgar had been conveyed to the Admiralty by Lieutenant Lapenotière, commander of the schooner HMS Pickle; or so Hawkwood had been informed by the clerk at the Falmouth coaching office. Lapenotière had supposedly made the journey by post-chaise in thirty-eight hours. Having no urgent dispatches to deliver, Hawkwood had been forced to settle for a slower ride. When he alighted from the un-sprung coach for the last time, it had felt as if his back had been stretched by the Inquisition. He wondered if Lapenotière had suffered from the same discomfort.

The Blackbird lay in a quiet mews off Water Lane, a stone’s lob from the Inner Temple. It was a short walk from the Saracen’s Head and the route had taken him down through the Fleet Market. It had felt strange, making his way past the shops and stalls, because even at that hour of the day they were crowded and after being surrounded by wide open seas and even wider skies during the crossing from America, the hustle and bustle of London’s congested streets, while instantly familiar, had come as something of a shock, as had the smells. After the clean air of New York State’s lakes and mountains and the bracing bite of the North Atlantic winds, he’d forgotten how much the city reeked. At the same time, it felt as though he’d never been away.

The Blackbird’s door had been open, in readiness for the breakfast trade. Maddie’s back had been to him. Her auburn hair tied in place with a blue ribbon, she’d been directing the serving girls as they’d flitted between the tables and the kitchen, taking and delivering orders. Hawkwood had waited until Maddie was alone before he’d enquired from behind with a weary voice if there were any rooms to be had. Maddie had turned to answer, whereupon her breath had caught in her throat and her eyes had widened.

The sound of her palm whipping across his left cheek had been almost as loud as a pistol shot. Breakfast diners within range had looked up and gaped; more than a few had grinned.

Hawkwood hadn’t moved as the burning sensation spread across his face.

Maddie Teague had stared up at him, her eyes blazing. Then, as quickly as it had flared, the anger left her and her face had softened.

“You could have written,” she said.

“On the bright side,” Jago said, chuckling. “She could’ve been carryin’ a bowl of hot broth or a carvin’ knife.”

“Lucky for me,” Hawkwood said.

“You made up, though, right? She didn’t stay mad?”

“No,” Hawkwood conceded. “She didn’t.”

“There you go then.” There was a pause before Jago added, “She asked if I’d heard from you.”

Hawkwood stared at him. “She never mentioned that.”

“Sent me a message. I called round; told her I hadn’t heard but I’d make enquiries.”

“That’s when you went to see Magistrate Read.”

“It was. He told me that, as far as he knew, you were still alive and that if anything did happen, he’d get word to me.”

“And you’d pass the word to Maddie.”

Jago nodded.

“She was angry,” Hawkwood said.

“Women are funny like that,” Jago replied sagely. “I told her not to worry; that no news was good news. Can’t say she was convinced. Think she was all right for the first month. After that …” Jago shrugged and then brightened. “I did put in a bid. Told her if anythin’ were to ’appen, and if she had trouble makin’ ends meet, I wanted first refusal on your Baker.”

“That was gallant. How did she take it?”

“Not well. Told me I’d have to join the bloody queue.” Jago’s face turned serious. “You do know that, if you hadn’t turned up, she’d have waited. There’s no one else. There’s plenty who’d like to step up but, until she heard otherwise, it’d be you she’d be holdin’ out for.”

“I told her she’d know if anything had happened,” Hawkwood said.

“Reckon we both would,” Jago said sombrely, and then he grinned once more. “So I’d still be in the queue for your bloody rifle. I’d raise a glass, too, though, for old time’s sake. You can count on that.”

“I’m touched,” Hawkwood said.

“Aye, well, you’d do the same for me, right?”

“Depends,” Hawkwood said.

“On what?”

“On whether you had anything worth leaving.”

“Jesus, that’s harsh.”

“The rifle would have been yours anyway,” Hawkwood said. “I’d already left provision.”

“Now I’m touched,” Jago said. “Mind you, the times I’ve watched your back, it’s the least you could do. And so’s you know, if I had bought a horse and carriage, I’d have left you them in my will.”

“You would, too, just to be bloody awkward.”

Jago grinned. “And then I’d come back to see the look on your face.”

Emptying his glass, he placed it on the table and looked up. “So, when you plannin’ on visiting the Widow?”

“Soon as I finish my drink.”

Jago raised a sceptical eyebrow. “Dutch courage?”

Taking a last swallow, Hawkwood pushed his chair back and got to his feet. “You ever hear of a black widow?”

“Don’t ring any bells. She a coloured girl?”

“No. It’s a type of spider.”

“A spider?” Jago said doubtfully.

“After she’s mated, she eats the male.”

Jago’s mouth opened and closed. Dropping his gaze, the former sergeant stared down into his own glass as if something might be concealed within it before lowering it slowly to the table.

He looked up. “Any of them around here?”

Hawkwood smiled grimly. “Could be I’m about to find out.”

7

Outwardly, there was nothing to distinguish the house from its neighbours. Not that Hawkwood had been expecting any sort of sign above the door. There might have been only a mile or so separating them but the square was a world away from the stews of Covent Garden and the alleys of Haymarket, where, for a pint of grog and a few pennies, you could negotiate a quick fumble in a doorway with a pox-ridden hag who was as likely to rob a man blind as to roger him senseless. Pennies bought you nothing here. The Salon provided for a far more affluent clientele, which meant there was no requirement for it to advertise. Its word-of-mouth reputation was enough, as was the locale.

Bounded on all quarters by three- and four-storeyed townhouses, the centre of the square had been laid out in the style of a formal garden, patterned with winding pathways, ornamental shrubbery and several tall plane trees, all protected by a palisade of wrought-iron railings that looked newly painted. In the far corner, on the square’s north side, could be seen the boundary wall of an imposing brick mansion set back from the street, more evidence that the further west you lived, the more affluent you were likely to be.

Traffic was light. A couple of carriages clattered past, harnesses clinking, followed by a trio of riders dressed in smart dragoon uniforms, while a handful of pedestrians picked their way carefully around the carpet of horse droppings that smeared the road. The smell of fresh dung lingered on the damp afternoon air.