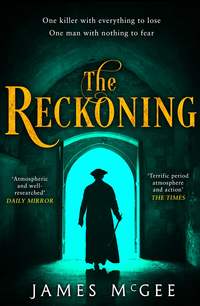

The Reckoning

Watching them trying to negotiate passage on to cleaner ground, Hawkwood wondered idly how many of the square’s residents were aware of the goings on inside this particular house. Most of them, he suspected. And how many of them had visited the premises? More than might be imagined, he was prepared to wager.

Approaching the black-painted front door, a quick glance at the windows above him revealed the drapes on the upper floors to be fully drawn. It was one indication that he’d come to the right address. In lower-ranked brothels, working girls used the windows to display their wares, leaving little to the imagination in the process. In contrast, the houses at the upper end of the scale masked their entertainments by shielding the view from the street.

Hawkwood pulled on the bell handle and waited. He sensed he was being perused for he’d seen the spyhole in the door. Debating whether or not to wipe his boots against the backs of his breeches, he thought, to hell with it. He’d had the breeches cleaned after his graveyard jaunt and he was damned if he was going to dirty them again that quickly. If whoever was studying him through the woodwork chose not to open the door because of his less than pristine appearance, he could always hammer on it with his tipstaff and yell, “I demand admittance in the name of the law!” It wouldn’t be pretty but it would be a very effective means of gaining entry, because the occupants wouldn’t want that sort of commotion on their doorstep. It would lower the tone of the neighbourhood.

He was reaching for his tipstaff when his summons was answered.

The manservant, a thickset, competent-looking individual in matching grey jacket and waistcoat, looked Hawkwood up and down, paying close attention to his greatcoat and his boots. When he glanced over Hawkwood’s shoulder towards the street, Hawkwood wondered if he was searching for the carriage that had dropped him off.

“I walked,” Hawkwood said, “all the way from Bow Street. I’m here to see the lady of the house, and don’t bother asking if I have an appointment.”

Because I’ve had enough of that.

At the mention of Bow Street, the manservant’s gaze flickered. The raised eyebrow that had been there when he’d opened the door was replaced by a new wariness.

Hawkwood sighed and took the tipstaff from his coat. “That would be sooner, rather than later.”

The manservant’s jaw flexed. “Name?” he enquired, stepping aside to allow Hawkwood entry.

Hawkwood resisted the urge to wipe the supercilious expression from the manservant’s face, gave his name and fixed the man with a look. “Yours?”

The manservant hesitated and then squared his shoulders. “Flagg.” Adding, somewhat reluctantly, “Thomas.”

Through what sounded like teeth being gritted, the manservant instructed Hawkwood to wait. Then, turning, he strode across the hall to a closed door, knocked and entered the room beyond, leaving Hawkwood to mull over a noticeable bulge in the back of the manservant’s jacket. A small cudgel stuck handily in the waistband, Hawkwood guessed; definitely not a pistol, which would have been harder to conceal.

Ellie Pearce – or Lady Eleanor, as she was choosing to call herself these days – clearly took the matter of personal security very seriously. Hardly surprising; most establishments of this sort – regardless of their status – employed protection in one form or another, some more covertly than others. Even girls working the street tended to have a pimp hovering nearby, though their presence had more to do with ensuring the safety of their investment than guaranteeing the girls’ welfare.

The manservant’s absence provided an opportunity to take in the interior of the house, which was as tasteful as the exterior had suggested it might be.

Given the greyness of the day, the lobby should have been cast in a sepulchral gloom, but by the strategic use of candles set in mirrored alcoves, the entrance hall was cast in a warm and welcoming glow. It was a far cry from the cheaper East End houses, which were apt to equal Smithfield on market day for both noise and activity. The main cause for the rowdiness was alcohol. In the rougher parts of the city, the only businesses that outnumbered the brothels were the gin shops.

Such was the ambience created here that a casual entrant could well have missed the more intimate items of décor that suggested the Salon might be something other than a comfortable family residence. These were in the form of porcelain statuettes set in niches around the walls depicting nude male and female figures entwined in a variety of sexual acts. The theme continued up the main staircase, which rose in a graceful sweep towards the first-floor landing, with each tread accompanied by a rising gallery of pencil-drawn images that were so graphic they made the cavorting figurines on the ground floor look positively chaste.

Somewhere above him, a door opened and closed softly, while from the ground floor, behind a door adjacent to the one through which the manservant had disappeared, there came the sound of a pianoforte, accompanied by a short and equally melodic burst of female laughter.

As if the laughter had been a signal, the door across the hallway opened and the manservant reappeared. He looked no happier than he had before as he caught Hawkwood’s eye, signalling that despite his own reservations and the state of the visitor’s wardrobe, the man from Bow Street had been granted an audience.

“Not your day, is it, Thomas?” Hawkwood murmured as he pushed past and entered the room. He didn’t wait for a reaction but felt the manservant’s eyes burning into the back of his neck as the door closed behind him.

By their ages, the two women could have been taken for mother and daughter, though it was the older one who was closest to the description given by Connie Fletcher. Connie had intimated that she and the Salon’s proprietress were around the same age. Connie, Hawkwood knew, was still on the good side of forty, though only by a year or two. What struck Hawkwood, as the former Ellie Pearce turned to greet his entrance, was that it wouldn’t have mattered whether she’d been a park-walker touting her wares behind the wall in the Privy Gardens or a costermonger’s wife; like Connie, she would still have turned heads. The thought occurred that maybe he should have cleaned his boots, after all.

It was her eyes as much as her profile and her smooth, near-porcelain skin that drew the attention. Deep indigo, framed by prominent cheekbones and what looked to be shoulder-length black hair drawn up and secured at the nape of her neck by a silver clasp, they regarded Hawkwood in frank appraisal, suggesting she was not best pleased by having her afternoon interrupted at the behest of an unknown and, more germanely, uninvited public servant.

In contrast, her younger companion, who was also slender but with blonde ringlets and clearly less reserve, greeted Hawkwood’s entrance with an openly suggestive grin.

“Officer … Hawkwood, was it? You must forgive Thomas his manners. He tends to be over protective when it comes to gentlemen visitors he does not know. Even now, I suspect he is listening without, ready to spring to my aid.”

There was not the slightest trace of Half Moon Alley in her voice. The refined, almost seductive tones could have belonged to any London society hostess.

“Thank you. I’ll bear that in mind.”

Surprised by Hawkwood’s dry riposte, Eleanor Rain frowned, while the younger woman clapped her hands and beamed as if she had just been gifted with a new puppy. “Oh, I like the look of this one. Can we keep him?”

The older woman held Hawkwood’s gaze for several seconds before turning and addressing her more forward companion. “Thank you, Charlotte. You may leave us.”

Pouting prettily but without protest, the young woman made for the door, taking time to mime Hawkwood a kiss as she wafted past, while allowing her thigh to brush the back of his left hand and the faint scent of jasmine to linger enticingly in her wake.

Eleanor Rain waited for the door to close before moving to a low, loose-cushioned sofa against which rested a small table, upon which was a tray bearing a China-blue tea service. Taking her seat, she brushed an imaginary speck of lint from her sleeve and regarded Hawkwood with cool detachment.

“How curious; I’m trying to recall the last time a representative of the constabulary came to call, but I declare it’s quite slipped my mind. Though, of course, members of the judiciary are always dropping by.”

The emphasis placed on the word “members” had been deliberate. It was her way of telling him that she regarded his visit as no more than a distraction and that, as a person of little consequence who could not possibly understand innuendo, his presence would be tolerated only for as long as it took him to state his business.

Hawkwood nodded. “After a hard day on the bench, no doubt.”

In the ensuing pause, the ticking from the clock on the mantelpiece sounded unnaturally loud.

Until that moment, Hawkwood had been having difficulty equating the woman seated before him with the Ellie Pearce who’d earned her living servicing a parade of men in the back room of a Smithfield public house, but as her expression changed in the face of his rejoinder he saw caution in her eyes and a growing realization that it was not just her own appearance that might be proving deceptive.

Her swift recovery also told him that this was a woman who was unashamedly aware of the effect her looks had on the opposite sex. If she’d been in the trade for as long as Connie had hinted, the half-smile she now offered in acknowledgement of his response would be as much a part of her repertoire as the way she held herself and her penetrating and provocative gaze.

Similarly, the dress she wore, while appearing simple in cut, served to add to her allure. Cream, with an ivory sheen and inset with fine blue stripes that matched the colour of her eyes, the high waist and hint of décolletage artfully accentuated her shape, with the clear intention of making life a little more interesting for aficionados of the female form.

Her choice of jewellery was as understated as her attire. A blue gemstone the size of a wren’s egg hung from a silver chain about her neck, the jewel resting above the gentle swell of her breasts. She wore a ring set with a smaller, similar-coloured stone on the third finger of her right hand, while her left wrist was encircled by a delicate bracelet, also made of silver to match the clasp in her hair and the fine linkage at her throat.

Leaning forward, she reached for the teapot, the motion deepening the shadow at her neckline, as she had known it would.

Hawkwood recognized it as part of a strategy designed to remind her visitor of his true place. Seated, she was Lady Eleanor Rain, granting him an audience. Standing, he remained the underling, the minion who, even though he was an officer of the law, meant there was not the slightest chance he would be invited to take tea. Tea was expensive – the caddy would be hidden away under lock and key – and the idea that she would consider sharing such a valuable commodity with someone she saw as being beneath her station was unthinkable.

He watched as, with precise, almost sensual deliberation, she proceeded to pour herself a cup, using a strainer to catch the leaves. When the cup was three-quarters full, she laid the strainer to one side. Adding neither milk nor sugar, she lifted both cup and saucer from the tray and cradled them in her lap.

Raising the cup to her lips, she took a small sip. Returning it to the saucer with exaggerated finesse, she straightened and regarded him expectantly. “Perhaps you should explain why you are here?”

Hawkwood, tiring of the game, decided to dispense with the niceties.

“I’m here to enquire if any of your girls are missing.”

It was not what she’d been expecting. Taken aback by the bluntness of Hawkwood’s response, she stared up at him. “Missing? I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

“A body’s been found.”

“A body?”

“A young woman.”

“I see. Well, that is distressing, but what makes you think she might be associated with my salon?”

“She had a rose tattoo on her upper arm. I’m told you’re familiar with such a mark.”

She stared at him without speaking.

Hawkwood matched her gaze. “Or have I been misinformed?”

He watched the indecision steal across her face, quickly replaced by a more guarded look, which did not make her any less attractive. Two more seconds passed. Then, lifting a hand from the saucer, she made a dismissive gesture. “An affectation; nothing more. A mark of quality, if you will.”

“Like Mr Twining’s tea?”

She blanched. Then, collecting herself once more, she looked up. “Do you have a description of this unfortunate young woman?”

“Petite, brown hair, blue eyes and young, as I said. We believe she was in her early twenties.”

Even as he uttered the words, Hawkwood knew the description was a poor one as it probably covered half the molls in London; a fact mirrored by Eleanor Rain’s less than engaged expression.

“And how did she die?”

“Painfully. Beaten and throttled, then tied in a sack.”

No point in mentioning the mutilation. It was always best to hold something back.

For the first time a look of genuine shock distorted her features. “Murdered,” she said softly.

“I doubt it was suicide.”

She coloured. “No, of course not. Forgive me, it’s …”

Returning the cup and saucer to the tray and placing her hands together on her lap, in a more composed voice, she said, “My apologies. It is difficult to gather one’s thoughts after being told of such a thing.” She drew herself up. “I can assure you, however, that all my ladies are accounted for.”

Hawkwood nodded. “I’m relieved to hear it. Though ladies do come and go, do they not?”

She frowned, as if the idea had not occurred to her. “They do, but surely I cannot be expected to account for the whereabouts of those who might have chosen to leave my employ.”

“That’s true. So has anyone flown the nest recently?”

“They have not.”

The answer came sharply but then she took another breath and in a considered tone said, “May one enquire when the killing took place?”

“We believe death occurred a day ago; perhaps two.”

“Where?”

“That we don’t yet know. I can tell you where she was found: in a grave, in St George the Martyr’s burying ground.”

“A grave?” she said, puzzled. “Then how …?”

“An open grave.”

Hawkwood watched her as the image ran through her mind.

“And she has lain there unseen until now?”

“Yes.”

“All that time? How terrible.”

“Murder usually is,” Hawkwood said.

Her chin lifted. Then, fixing him with a conciliatory look, she said, “And it is your task to discover who was responsible?”

“It is.”

She nodded. “Could the perpetrator strike again?”

“It’s possible, yes.”

“So until you find him, we are all of us at risk.”

“I can’t say you won’t be. We don’t yet know his motive.”

“You’re saying she could have been killed for who she was, rather than for what you think she was?”

“Yes.”

“And a rose is not an uncommon adornment. She could just as easily be a washerwoman as a whore.”

“She could.”

Her eyes clouded. In that instant Hawkwood caught his second glimpse of the woman behind the mask; a woman who, by force of will, had managed to haul herself out of the gutter and into the privileged ranks of society, all the while knowing and resenting the fact that there were elements of her previous life still buried deep within her that she would never be able to erase.

There was fear there, too, he suspected; fear that, one day, someone would confront her and remind her of her former existence. It was the most vulnerable chink in her armour and she was wondering if this was the moment that weakness was about to be exploited. The sudden flare in her eyes was a warning sign that she would defend her reputation to the hilt if she felt it was about to be challenged.

“Which is why we need to confirm her identity,” Hawkwood said, and watched as the fire died away.

“Because, whatever their reasoning, the sooner you find the person who killed her, the safer we all will be?”

“Yes.”

“Then I am sorry I’ve kept you from your task and that your journey here has been wasted.”

“Not at all. All enquiries are useful.”

Acknowledging Hawkwood’s response with a small – possibly appreciative – nod, she said, “I will, of course, enquire of my ladies if they have heard of or know of anything that could assist your investigation.”

“That would be most helpful. Thank you.”

“It is the least I can do.” She paused again and said, “And if I should come into possession of information which might be relevant, how may I notify you?”

“Through Bow Street Magistrate’s Court.”

“Yes, of course.”

As if in need of some activity to fill the subsequent pause in the conversation, she retrieved her cup and took an exploratory sip. Finding the brew had grown cold, she wrinkled her nose and returned both cup and saucer to the tray, leaving a faint smear of pink lip salve along the cup’s rim.

Hawkwood judged this the opportune moment to take his leave, but as he turned to go she said suddenly, “When Thomas announced you were from the Public Office, I confess, you are not what I was expecting. I apologize if my manner was less than courteous. You are a Principal Officer … what they call a Runner, yes?”

Hawkwood wondered where this was going. “We prefer the former, but yes.”

She permitted herself a smile. “Duly noted. It has been my experience that most Public Office employees look incapable of breaking into a brisk walk, let alone a run, whereas you look, if I may say so, rather more … capable. You have the air of a military man. Would I be right in thinking you have fought in the service of the king?”

“I was in the army.”

“I thought as much. I made a small wager with myself when I saw the scars on your face and the cut of your coat. It is military-issue, is it not?”

“It is.”

“You look surprised. Did you think I was uninformed about such matters? If I were to name every colonel who sought sanctuary within these walls, we would be here until Easter. I believe I could also name not only every regiment in the British Army, but every fourth-rater in his majesty’s navy, given the number of admirals that have raised their flags in my establishment. Not to mention magistrates, ambassadors, assorted aristocrats, clergymen and all but two of Lord Liverpool’s cabinet. You were an officer, yes?”

Hawkwood didn’t get a chance to respond.

The smile remained in place. “In this profession, if you learn one thing, it is how to read men. Your attire betrays you. Your outer wear may have seen better days, but your boots are of good quality, as are your jacket and your waistcoat, from what I can see of them. It is also in the way you carry yourself.”

The blue eyes narrowed. “You would not have moved from colonel to constable – my apologies, to Principal Officer. That would be too far a step down, I think. Too old for a lieutenant, so you were either a captain or a major.”

Tilting her head, she went on: “You look like a man who is used to command and yet you have little respect for authority. I suspect you came up through the ranks and proved yourself in some engagement, therefore I choose the former. You were a captain. Am I right?”

“And there was I, thinking I hadn’t made a good impression,” Hawkwood said.

The frown returned. “Yes, well, in that you are not wrong. Your manners could certainly use improvement. An officer you may have been, but you display the attitude of a ruffian. Has anyone ever told you that?”

“Once or twice.”

“Or perhaps it is a deliberate strategy, like the employment of sarcasm,” she countered tartly.

“It comes in useful when I don’t have a pistol to hand.”

Unexpectedly, the corner of her mouth dimpled once more and her gaze moved towards the clock on the mantelpiece. Turning back, she said, “Yes, well, unfortunately, much as I’ve enjoyed our conversation, I see time is against us. I have an evening’s entertainment to arrange, so you must forgive me.” She gazed at him beguilingly. “Unless there is anything else you wish to ask?”

“Not at this time. I may need to call on you again at some date.”

She inclined her head. “Of course.”

Hawkwood was about to turn for the door, when she said quietly, “I think, perhaps, I should like that. Despite your questionable manner and the reason for your visit with all this talk of graveyards and murder, you have enlivened what would otherwise have been an exceedingly dull afternoon.”

Her eyes held his. “I have the distinct feeling that there is more to you, Captain Hawkwood, than meets the eye. I suspect that, were I to scratch the surface, I would unearth all manner of interesting truths. Why is that, do you suppose?”

“I have no idea,” Hawkwood said, “though, curiously, I was thinking exactly the same thing about you.”

She continued to regard him coolly for several seconds. “Then, perhaps, if your investigation allows, you might consider visiting in a more … private capacity?”

“On my salary? I doubt it.”

“Then you do yourself a disservice. Attendance is not solely dependent on the depth of one’s purse. If you were to attend, it would be at my invitation.”

She let the inference hang in the air between them.

“I wouldn’t want to lower the tone,” Hawkwood said.

She smiled, more warmly. “Oh, I think you’ll find we cater for most persuasions. Who knows? You might even see something you like. And as I mentioned earlier, you would be in excellent company. Our evening soirées are extremely popular.”

“I’m sure they are.”

Raising her hand, she caressed the jewel at her throat. “Well, then, will we see you again?”

“Perhaps.”

“Perhaps? That sounds like a man contemplating retreat. I do hope we haven’t frightened you away.”

“I’d prefer to call it a strategic withdrawal.”

She bit back a smile. “In order to advance again at a more opportune moment?”

Before he could reply, she rose sinuously. “If that is your intention, I should probably summon reinforcements. Before I do, though, let me give you this.”

From the white marble mantelpiece she took a small silver box. Opening it, she removed what looked like a deck of playing cards. Selecting a card, she held it out. “Should you decide to call.”

There was no script. One side of the card was plain and coloured black. When Hawkwood turned it over he saw that the face side was embossed with the image of a red rose on a white background.

She picked up a small hand-bell from the table. At the first ring, the door opened. Flagg stood there, poised and looking not a little disconcerted to find that Hawkwood was still standing and in one piece.

“Madam?”

“Thomas, if you would be so kind as to show the officer out. We have concluded our business. Oh, and treat him kindly, otherwise we might not see him again. And that, I think, would be rather a pity.”

Ignoring the manservant’s baleful look, she inclined her head. “Until next time.”

Hawkwood slid the card into his waistcoat pocket, by which time she was already turning away. As dismissals went, it was hard to fault.

“Ever wear a uniform, Thomas?” Hawkwood asked, as the manservant walked him through the lobby to the front door.

The reply was a borderline grunt. “East Norfolk, First Battalion.”

Hawkwood nodded. “Thought as much; seems there’s a lot of it about.”

The manservant frowned but did not respond. He remained silent as he let Hawkwood out.

A light drizzle had begun to fall. As the door closed behind him, Hawkwood turned up his collar and walked away into the rain.