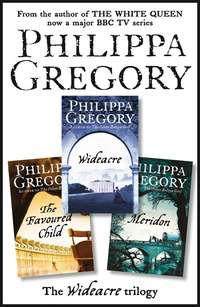

The Complete Wideacre Trilogy: Wideacre, The Favoured Child, Meridon

‘Will you be away very long, Miss Lacey?’ he asked in his gentle Scots voice.

‘Just till Christmas,’ I said. ‘I could not bear to be away from home at Christmas and Harry and I both want to be back in plenty of time for the spring sowing.’

‘I hear you are a keen agronomist?’ He said it without a hint of the patronizing amusement I was used to from neighbours whose lands yielded half the profits of ours and yet thought my interest unbecoming.

‘I am,’ I said. ‘My papa reared me to take an interest in our land and I love Wideacre and am glad to learn all I can about it.’

‘It is a fine thing to have such a lovely home,’ he said. ‘I have not the advantage of a country seat. My family has always bought and sold property so frequently I never had a chance to put down roots.’

‘You are an Edinburgh family?’ I asked with interest.

‘My father owns the MacAndrew Line,’ he said diffidently. At once, pieces of information slipped into my head like the solution to a puzzle. His presence in the Haverings’ house was explained at once. The MacAndrew Line was a highly successful line of trading ships plying from London, Scotland and India. This young doctor came from a family of fabulous wealth. Lady Havering would be swift to overlook his unusual profession in return for a chance at one of the greatest fortunes in Britain. She would have already earmarked him for one of the girls, and Lord Havering would already have tried to persuade the young doctor to invest in some sure enterprise that his lordship could set in motion if he only had the advantage of a few of the MacAndrew thousands.

‘I am surprised he could spare you so far from home,’ I said.

Dr MacAndrew laughed shortly. ‘I’m afraid he was unhappy when I left the family home and the family business,’ he said. ‘He wanted very much for me to work with him, but I have two older brothers and a younger one as well who will do that. I set my heart on medicine ever since I was a young boy and despite my father’s objections I managed to get my training at the university.’

‘I should not like to have much to do with sick people,’ I said, speaking without reserve to this gentle young man with the warm eyes. ‘I don’t have the patience.’

‘No, why should you?’ he said sympathetically. ‘I should like everyone in the world to be as fit and as strong as you. When I have seen you galloping your horse up to the downs, I have laughed with sheer pleasure at such a brilliant sight. You would not fit in a sickroom, Miss Lacey. I would always prefer to see such youth and loveliness in the open air.’

I was flattered. ‘You should not have seen me galloping at all,’ I said demurely. ‘I was not supposed to go off the estate while we were in mourning, and I should never gallop in public. But when one has a good horse, and the wind is blowing just softly, I cannot bear not to.’

He smiled at my enthusiasm and fell to talking of horses. I had noticed, even in the period of my illness, that he had a good eye for a horse. The bays that pulled his curricle were a splendid pair: high-stepping, arch-necked, ruddy-bronze.

I had even wondered idly where a young doctor found the money to buy such beauties, but now he had explained that. I told him about the first pony Papa bought me, and he told me of his first hunting dog, and I forgot that half the eyes of the room were on us.

‘Beatrice, dear …’ my mother said hesitantly. I glanced up to see Lady Havering bearing down upon us. She swept Dr MacAndrew off like a competent hostess, to meet some of the other guests, and my mama reminded me that I must take Celia upstairs and help her change out of her wedding gown for the journey.

The extent of my help was gazing dreamily out of the window while Celia’s maid bustled about, and making sure that my own cloak and bonnet were smooth and straight. I was miserable at leaving Wideacre. I could hardly bear to leave the familiar sight of the hills with the trees just starting to turn colour, and there were tears in my eyes as I kissed Mama goodbye and jumped into the carriage. She, silly dear, took them for herself, and kissed me warmly and blessed me. In the crowd of people around the post-chaise, kissing Celia’s hand and calling out reminders and good wishes, I looked for Dr MacAndrew. He was standing at the back of the crowd and his eyes met mine. There was a little warm smile in them, especially for me, and I felt suddenly still. In the noise of the crowd I could not hear what he said, but his lips formed three words, ‘Come back soon.’

I sat back in the chaise with a smile on my face and a certain warmth around me as we drove off on honeymoon.

The wedding night was all that Harry and I had planned, with the added excitement for me of deceiving Celia who was sleeping next door. Harry had to hold his hand over my mouth to smother my cries of pleasure, and that hint of his violence and my helplessness excited us even more. When his own time came he had to thrust his face into the soft pillows to muffle his long, low groans. Afterwards we lay in silence and peace and I did not trouble to creep back to my own room.

The Golden Fleece at Portsmouth is near the harbour walls and as we drifted into sleep I could hear the wash of the sea as the waves smacked the fortifications. The smell of the salt air made me feel that we were already on our journey and Wideacre hopes and Wideacre fears were far away from us. Harry sighed heavily and turned over, but I lay quiet in the strange room savouring the distance from home – while secure in the awareness that I had made it more my home than ever before. Unconsciously, my thoughts drifted to Ralph – the old Ralph of my girlhood – and his longing to lie with me between sheets in a clean bed. He was right to envy us. Land, and the wealth that land brings, is essential.

I lay on my back gazing clear-eyed into the darkness, listening to the waves wash against the harbour wall as if they were sighing for the touch of the land. I had Harry now, and next door Celia slept, secure in my friendship. The old nagging ache in my heart, my fear of not belonging, of not being loved, had eased. I was loved. My brother, the Squire, adored me and would come to me at the snap of my fingers. I was safe on the land. He owned the land outright and would do my bidding. But I gazed unseeing at the grey ceiling of the bedroom and knew it was not enough. I needed something beyond him, something more. I needed whatever magic had possessed him when he brought in the harvest like a living sheaf of corn himself, golden-headed, golden-skinned, tall on the mountain of wheat. When I had stepped out of the shadow of the barn I had greeted not only the man I desired but somehow something more: I greeted the god of the harvest, and when he gazed at me he saw the old dark goddess of the earth’s green fertility. When he became a man in a nightshirt, snoring softly, I lost that vision and I lost my passion too.

Of course I thought of Ralph. In all our meetings and kisses in the sunny days of caresses in hiding, the magic never left Ralph. He was always something dark from the woods. He always breathed of the magic of Wideacre. But Harry, as he said himself, could live anywhere.

I rolled on my side and cupped my body around Harry’s plump bottom ready for sleep. I could never have managed Ralph as I could control Harry. I could never have brooked a master, but I could not help a secret squirm of disdain for a man I could train as easily as a puppy. Every good rider likes a well-trained horse. But who does not enjoy the challenge of an animal whose spirit you cannot break? Harry always was, always would be, a domesticated pet. And I was something from further back, from wild days when magic still walked in the Wideacre woods. I smiled at the picture of myself as some lean, rare, green-eyed animal. Then I dozed. And then I slid deep, deep into sleep.

The bustle of the hotel woke me in plenty of time to slip through the adjoining door to my bedroom long before my maid had brought my morning cup of chocolate and hot water for washing. I could see the harbour from my bedroom and the water was a welcoming blue with fishing boats and yachts bobbing on the little waves. I was alive with anticipation and excitement, and Celia and I laughed like children as we boarded the ferry moored beside the high harbour wall.

The first few minutes were delightful. The little ship rocked so sweetly at its moorings, and the sights and smells were so new and strange. The harbourside was crowded with people selling goods to the travellers. Fruit and food to take on the journey in little baskets, little painted views of England for travellers going home to France, hundreds of little worthless pieces of trumpery made from shells or pretty pieces of glass.

Even the sight of a legless man – a wounded sailor – did not make me tremble with a sense of my danger coming closer and closer. Although I gazed in horror at the stumps of his thighs and saw how deft, how disgustingly skilful he was at swinging around on the ground – I had seen at the first sight that his hair was light-coloured and I was secure in the knowledge that in leaving Wideacre I was escaping Ralph and his slow, inexorable approach. I threw the beggar a superstitious penny, and he caught it and thanked me with a professional whine. The thought of Ralph, my lovely Ralph, reduced to poverty and squatting on pavements caught at my heart. But then I shrugged the idea aside as Celia called, ‘Look! Look! We are setting sail!’

Lithe as monkeys, the sailors had swarmed up the double masts and unfurled sheets of canvas. They tightened the ropes as the sails flapped and billowed, and amid raucous shouts and curses the bystanders on the harbourside slipped the ropes free and threw them into the boat. Celia and I shrank out of the way as the men, as wild-looking as pirates, dashed from one rope to another heaving the sails up and tying the ropes tight. The harbour wall slid away from us and the people waving seemed very small, then the ship moved out to the harbour mouth where the arms of yellow stone seemed to try to hold us for one last second to England and home. Then we bounced through the boiling waters where river and ebbing tide meet the sea and scudded out.

The sails filled with wind and stretched and thumped and the men dashed around less, which Celia and I took to be a good sign. I went to the prow and, glancing around to ensure that no one was watching, stretched myself out along the bowsprit as far as I dared, to watch the waves rushing beneath me and the sharp prow cutting into the green waters. A good hour I spent there, fascinated by the rush of the waves, but then the rocking became more and more fierce, and although it was midday, the sky darkened with the deep clouds that mean a storm on land or sea. It started to rain, and I found I was weary. I had to sit in the cabin out of the rain and the rocking was no longer pleasant and it was very tiring to see the room going up and down.

Then it was not just tiring, but unbearably horrid. I felt sure I should be well if I could be up on the deck again, and I tried to hold to the memory of the pleasure of the prow cutting through the water. But it was no good. I hated the boat, and I hated the senseless rocking of the waves and I longed with all my heart to be back on the good solid earth.

I opened the cabin door and called for my maid who should have been in the cabin opposite mine. A sudden rush of nausea sent me to the basin in my room. I was sick alone and without help, and then a jerk and a dive of the ship sent me reeling into my bunk. Everything in the cabin swayed and rocked and the unsecured bags slid from side to side and crashed into one wall and then the other. I was miserably ill, too ill even to help myself. I clung to the side of the pitching bunk and wept aloud in fear and in sickness and for help. Then I was sick again and I dropped on to the pillows which bumped horridly up and down; then I slept.

When I woke the cabin was still shifting and heaving but someone had packed away all the bags so the cramped little room seemed less nightmarish. There was a pale smell of lilies and everything was clean. I looked around for my maid, but it was Celia sitting calmly in a heaving, pitching chair and smiling at me.

‘I am so glad you are better,’ she said. ‘Do you feel well enough to take something? Some soup, or just tea?’

I could not puzzle out where I was, or what was happening. I just shook my head, my stomach churning at the thought of food.

‘Well, sleep then,’ said this strange, authoritative Celia. ‘It is the best thing you can do, and we shall soon be safe and calm in port.’

I closed my eyes, too ill to care, and slept. I woke once more to be sick, and someone held a basin for me, and deftly washed my face and hands with warm water, dried me and laid me back on the turned pillow. I dreamed it was my mother, for I knew it was not my maid. Only in the night when I woke again did I realize it was Celia nursing me.

‘Have you been here all the time?’ I asked.

‘Oh, yes,’ she said, as if nothing could be more natural. ‘Except when I was looking after Harry, of course.’

‘Is he ill, too?’ I asked wonderingly.

‘Rather worse than you, I am afraid,’ Celia said calmly. ‘But you will both be perfectly well when we reach France.’

‘Don’t you mind it, Celia?’

She smiled, and her gentle voice seemed to come from a long way away as I slid back into sleep.

‘Oh, no,’ she said. ‘I am stronger than I look.’

Next time I awoke the dreadful pitching and tossing had stopped. I felt light-headed and faint, but was no longer retching. I sat up and stretched my bare feet to the floor. I felt shaky, but better already, and tiptoed to the adjoining door to Harry’s cabin without holding the chair for support. The door opened without a sound and I stood silently in the doorway.

Celia was standing by Harry’s bunk with a bowl of soup in one hand, and her arm around Harry, around my Harry’s shoulders. I watched as he sipped at the soup like a sickly infant, and then Celia settled him back on the pillow.

‘Better?’ she asked, and her voice was infinitely tender. Harry clasped her hand.

‘My dear,’ he said, ‘you have been so kind, so sweet to me.’

Celia smiled and smoothed the hair from his forehead in an intimate, confident gesture.

‘Oh, how silly you are, Harry,’ she said. ‘I am your wife. Of course I care for you when you are ill. I promised to love you in sickness and in health. I have been happy to care for you, and for dear Beatrice, too.’

I watched in horror as Harry took Celia’s hand from his hair and held it gently to his lips. And she, the cold, shy Celia, bent and kissed him on the forehead. Then she drew the curtains around the bed. I stepped back, silent on my bare feet, and closed the door behind me. Celia’s confidence, Celia’s tenderness to Harry, amazed and alarmed me. I felt once more the knife thrust of jealousy, but also the fear of exclusion from the pale of the married state. For courage, for the reassurance of my beauty, I turned to the small mirror nailed on the wooden wall of the cabin. I was white and sickly looking, and my skin was like wax.

Any ideas I had of striding into Harry’s cabin and raging at him or even of slinking into his bunk beside him were instantly dismissed. If he was feeling at all as I did, he would welcome neither a quarrel nor a passionate reconciliation.

I dressed, a puzzled frown still on my face. For the first time now we were unlike ourselves in illness, and unlike ourselves off our land. It struck me how little I shared with Harry. Away from Wideacre, away from my obsession, and too tired to be lovers, we were strangers. If I had gone into his cabin for anything other than a scene of passion, I should not have known what to say. It would never occur to me to order soup for him, or to feed him as if he was some disgusting, overgrown baby, or to draw his curtains so he could sleep. I had never nursed any invalid; I had never even played with dolls in my childhood, and I had neither instinct nor interest in the kind of lovemaking that consists of gentle caresses and kindly courtesies.

Celia blooming with a sense of her importance and Harry expansive and grateful for her nursing were an odd couple indeed, but I could not see there was any way to check their new relationship.

Nor did I, once I was up on deck watching a beautifully steady horizon, think it necessary to spoil Celia’s moment of glory. If she liked to nurse Harry and me when we were hideous with seasickness, it was not a job I envied. And if Harry kissed her hand in gratitude, and thought of her drudgery kindly, well that did me no harm either. As the wind whipped my cheeks into a rosy colour, and my loose hair into curls, my hopes rose too. Here was France, and a long easy holiday with no eyes to watch us, no ears to listen to us, and only naive, silly, slavish Celia to deceive.

Harry and Celia joined me on deck, and I even forgave their interlaced arms – especially when I saw that my strong and healthy lover was leaning on Celia for support. He was pale and listless and smiled at me only when I assured him that we would be disembarked in under an hour. But I was no longer anxious. As soon as Harry was well and his appetite restored – for his dinner and for everything else – he would be mine for the taking.

We dined and slept that night in Cherbourg, and in the morning Harry was perfectly well. I did not complain, but I could not eat my breakfast for a renewed bout of seasickness. The dizziness had gone, but as soon as I lifted my head from the pillow I felt sick and extremely unlike myself. The others breakfasted on coffee and rolls, while I strolled outside in the fresh air of the garden of the inn, and watched them loading up our post-chaise. I somehow dreaded the long road to Paris cooped up inside a swaying carriage, and could scarcely raise a smile in response to Harry when he handed me up the steps.

My seasickness stayed with me, far from the sight of the sea, far from the smell of the boat. Damn it, it stayed with me every morning along the road to Paris, every sunlit Parisian morning when Harry hammered on the door and called to me to come riding in the bois, every morning of our journey south.

I lifted my head from retching into the window box one morning and admitted miserably to myself the fact I had been avoiding. I was with child.

We were three days’ journey from Paris, and in the heart of the French countryside and I stared out at a sea of roofs of a pretty old town and breathed air too hot for an English autumn. Then I smelled baking and some dreadful hint of spice or garlic too, and I retched again, but my belly was empty and nothing came.

Tears had squeezed from my swollen eyelids and I felt them cold on my cheeks as if I were weeping in sorrow. The pretty blue-slated roofs, the tall old church tower, the bluish horizon, all shimmering in a comfortable haze of heat, which had no power to warm me. I was with child. And I was afraid.

We were driving on that day; the others would be waiting for me below. I had lied and said I had forgotten something in my room to escape their eyes when I felt the flush coming to my face and my sickness start. Now I had to go downstairs, step into a post-chaise and spend nearly all day swaying and rocking on the rotten French roads and listen to Celia reading from her damned guidebook, and hear Harry snoring as he always, always did. And to no one could I reach out a quick hand of desperate need and say, ‘Help me! I am in trouble!’

Every morning when I had felt so strange I had secretly known. When I had failed to bleed at the usual time, I had blamed the excitement of the wedding and the journey. But I had known in my heart for at least a week, perhaps two. I simply could not face the thought. And, more like Harry and Mama than my usual clear-headed self, I had hidden the idea from myself. But it came back to me. Every sunny morning when I woke ill and anxious. Through the day while I smiled at Harry and chatted to Celia, I could forget and reassure myself with an easy lie that it had all been a reaction to the travelling, that I was well again. And at night, when I was in Harry’s bed and he thrust deep inside me, I could hope, in a little secret place in my head, that our clinging passion would make me bleed. But each morning was the same. And, more frightening, every morning was worse until I feared Celia’s loving sharpness would notice and I would fail in my fatigue and loneliness to keep this secret well hidden. That my need for help and my need for love, for someone, anyone, to say, ‘Do not fear. You need not face this alone,’ would overcome my good sense.

For I was very much afraid, and very much alone, and I dared not think what was going to happen to me.

I took my handkerchief out of my reticule as my excuse and went downstairs. Celia was waiting in the hall while Harry paid the bill. She smiled when she saw me and I could feel my face muscles were too stiff to reply.

‘Are you all right, Beatrice?’ she asked, noting my pallor.

‘Perfectly,’ I said shortly, and she took my abruptness as a rebuff and said no more, although I was longing to weep and throw myself into her arms and ask for her help to save me from this threat over my future.

I had no idea what I was going to do.

I climbed into the coach as if I were going to my death, and stared blankly out of the window to discourage Celia’s chatter. Counting on my fingers under the shield of my reticule I calculated that I was two months pregnant and that I could expect my confinement in May.

I stared in impotent hatred at the sunny French landscape, at the squat little houses and the dusty well-dug gardens. This foreign land, this strange place, seemed all part of the nightmare of my predicament. I was mortally afraid that the worst would happen and that I would die here in a shameful childbirth and never see my lovely home again. And my body would be buried in one of these horrid, crowded graveyards and not at Acre church where I belonged. A little sob escaped me and Celia looked up from her book. I felt her eyes on me but I did not turn my head. She put her little hand out and touched my shoulder with a gentle pat, like a caress one would make to an unhappy child. I did not respond but that token gesture comforted me a little and I blinked away the tears.

For two or three days of that miserable journey I rode silent in the carriage. Harry noticed nothing. When he was bored he rode on the box to see the view better, or hired a horse and rode for pleasure. Celia watched me with alert tenderness, ready to speak or be silent, but did not intrude on my brooding wretchedness. And I said nothing, kept my face serene when Harry was by, and gazed blankly out of the window when we were alone.

By the time we arrived at Bordeaux, I was over the first of the shock; my mind had stopped reeling like a drunkard. My first thought was to lose this little encumbrance and I told Harry I wanted a hard day’s riding to shake the fidgets out of me. He looked doubtful at the stables when I picked out a wicked-looking stallion and insisted on a lady’s saddle. They all advised against it. They all were right. Not even in the prime of health could I have stayed on that horse and he threw me in the first ten seconds in the stable yard. They rushed to help me to my feet and I was able to smile and say I was not hurt, I merely wanted to sit still. I sat and waited. Nothing seemed to have happened. I returned to my hotel room and waited for the rest of the day. The warm sunshine of the French autumn poured through the window and I scowled at it in an aversion for everything fruitful and strong. The pretty sunlit room was too small; the walls seemed to be closing in on me. The air was unbreathable and France itself stank. I snatched up my bonnet and ran downstairs. Harry had hired a landaulet for our stay in the town and I ordered it to be called to the door as Celia came slowly downstairs after me.