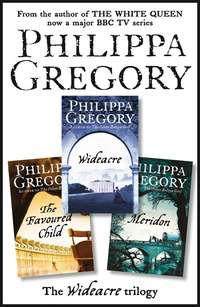

The Complete Wideacre Trilogy: Wideacre, The Favoured Child, Meridon

‘Are you going to drive alone, Beatrice?’ she asked, surprised.

‘Yes,’ I said tersely. ‘I need some fresh air.’

‘Shall I come with you?’ she asked. This non-committal tone had irritated me excessively in the early weeks of the trip, but I had learned soon that it was not that Celia lacked opinions – she simply desired to please me.

Her questions – ‘Shall I come to the theatre?’ ‘Shall I come to dinner with you and Harry?’ – meant simply what they said – ‘Would you prefer my company, or would you rather be alone?’ – and Harry and I soon found out that it did not offend Celia whether we refused, or accepted.

‘Don’t come,’ I said. ‘Make tea for Harry when he comes in. You know how he likes it, and the servants here cannot make it. I shall not be long.’

Celia acquiesced with a smile and watched me leave. I kept my face calm as I passed the windows of the hotel but, once out of sight, I dropped the little veil on my bonnet and wept behind it.

I was lost, lost, lost. And I could not think, I could not make myself think, what to do. My first thought had been to tell Harry and, between the two of us, concoct some solution. But some wiser voice in my head cautioned me to wait and not to panic into a confession I could not retract.

If I had been at home, in the old days, my first visit would have been to Meg, Ralph’s white witch of a mother. But I dismissed the memory of her with a shrug. I had known, as every country child knows, that girls gone into service, girls betrothed to the wrong man, or girls seduced by men already married, could rid themselves of their difficulties with the help of women like Meg and some secret, semi-poisonous plants. But never had I known what these were – nor would I have known how to use them.

Undoubtedly this sleepy French market town, like any other, would house a wise woman who could advise me. But I should not be able to find her without the whole inn, and thus every passing English visitor, hearing of the gossip. Short of a lucky, natural accident – and God knows I had terrified Harry and myself and been bumped and bruised but got no further forward – I was stuck with this growing weed.

I directed the coachman to drive on when he paused, waiting for instructions.

‘Go on, go on,’ I said fiercely. ‘Out to the country, just keep driving.’ He nodded his head and cracked his whip in obedience to the eccentric young Englishwoman. The carriage rolled out of the town and the houses gave way to little cottages surrounded by small gardens of dust. Then we were beyond the town limits, in the fields, the rows and rows of vines stretching for ever to the blue sky.

I stared miserably at the gentle, hilly landscape, so unlike the skyline of my lovely Wideacre. Whereas our hills roll up, part covered with beech coppices and crowned with caps of smooth sweet turf, these hills are terraced and walled every inch of the way with the monotonous vines broken only by peasant plots. It may be a pleasant country to visit, to bowl along a dusty road under a hot un-English sun, but I would not choose to be poor in France. Our people are far from wealthy – I would be overpaying them if they were – but they do not scrape and scratch a living from dry earth as the peasants do in France. Harry and I had learned much, driving round and talking to the leading landowners, though it was striking how few of them knew anything of their lands beyond the château gardens. But above all else we had reassured ourselves that the combination of new agricultural methods with a reliable labouring force was the way ahead for Wideacre.

A sudden bolt of homesickness shot through me and I thought with longing of my house and my land, and how I wished to be there now, and not in this strange and arid country with my dresses growing tighter around my breasts. Then the pain of homesickness suddenly crystallized into a thought in my mind so bright and so brilliant that I sat up with a yelp, and the driver reined in again to see if I was ready to go home. I waved him on and fell back in my seat, my hands instinctively clutching my slightly rounded belly. The child in there – this beloved baby that I had thought of only seconds ago as a growing weed – was the heir to Wideacre. If it were a boy – and I knew with certainty that it was a boy – then he was the future Master of Wideacre and my place there was assured for ever. Mistress in all but name of those most precious acres, and the mother of the son of the Squire. My baby would be the Master.

At once I felt different. My resentment melted away. I should hardly care for this discomfort, or even the pains, because these would be caused by the precious son growing and growing until he could be born into his rightful place.

Again I thought of telling Harry and gambling on his pride at the conception of a son and heir. But again, my instincts warned me to tread carefully. Harry was mine, very much mine, and this trip had proved it. Every evening as darkness fell and they brought candles to our rooms, or lanterns if we were dining outside, his eyes would turn to me and he would see nothing but the gleam of my hair in the flickering light, and the expression on my face. Then Celia would quietly excuse herself and leave us alone. The evenings and the nights were mine, and mine alone; and Harry and I pleasured each other for long hours and then fell asleep in each other’s arms. The days, however, I had to share him with Celia, and I noted, but could not prevent, the birth of an easy, affectionate intimacy.

Ever since the time on that cursed boat, Celia and Harry had established a way of being easy together. She loved to be of use to Harry, to comfort him when he was tired, or to rearrange the rooms in our various hotels so they were elegant, yet comfortable. The painfully shy Celia, with her halting command of the French language, would sally down to the strange kitchens to confront the master chef with demands for tea. She would stay there, ignoring the outrage of the French domestics, until she had watched them make it exactly to Harry’s liking.

She was amusingly protective of the man I knew to be all my own, and I permitted her this area of activity as a harmless hobby and one that freed me from the chores of housekeeping. It was Celia who packed and repacked the linen and the bedding every time we moved from one hotel to another. It was Celia who sought out tailors, laundries, bootmakers, florists and all the services we needed. It was Celia who repaired with exquisite small stitches a tear in Harry’s embroidered waistcoat, and it was Celia’s task to serve Harry like a maid while it was mine to amuse and delight him like an equal.

She was more confident after the tense night in Paris when they had become, finally, man and wife. Harry and I had jointly chosen the evening when he was to do his duty by her, and I had ensured that he regarded it as a disagreeable task. I had worn a low-cut dress for our outing to the opera and to supper afterwards. I had cast off my mourning with my first step on foreign soil, and that evening I shimmered in green like a young silver birch tree. My hair was thickly powdered white, and it showed my skin the colour of clear, dry wine. Not an eye in the hotel moved from me as Harry, Celia and I went to our table. Celia, beside me in pale pink, was eclipsed.

Harry drank heavily and roared with laughter at my witty talk. He was as tense as a wire and his nervousness took him to the edge of insensitivity towards Celia’s feelings. She looked more like a prisoner on the way to the guillotine than a bride. She was sickly white in her girlish dress, spoke not a word and ate not a thing all evening. I sent Harry in to her bedroom certain that nothing could be done further to guarantee a pleasureless period of duty and pain for both.

He was even quicker than I expected. He came to my room in his dressing-gown with his night-shirt still stained with her blood. ‘It is done,’ he had said briefly and rolled into my bed. We slept together in warm companionship – as if I were comforting him for some secret sorrow. But in the morning, when the first grey light of the Paris dawn crept through my shutters, and the noise of the water-carts on the cobbles outside woke us both, we made love.

But it was a measure of Celia’s new maturity – which I noted without comment – that not one word about that night of pain did I hear from her. Little confiding Celia told me nothing. Her intense loyalty to her husband – Harry the friend, Harry the invalid, and even Harry the legal rapist – kept her silent. She said nothing. She neither speculated, nor directly commented, on how long Harry and I sat together in the evening after she had retired. When she found Harry’s bed untouched one careless morning when we had overslept, she said no words, assuming Harry had fallen asleep in his chair, or perhaps privately speculated that he was with a woman. She was the perfect wife for us. I expect she was deeply unhappy.

But it was Harry’s response to her that made me pause. He had seen, as I had, Celia’s unswerving loyalty to himself, to me, and to our family name. I saw his appreciation of her tentative services to his comfort. I noted his meticulous courtesy to her and the growth of confidence and trust between them. There was no way I could stop this short of a battle that could only expose me. But also there was no reason why I should. Celia could have the hand-kissing, and the courteous rising when she entered the room, Harry’s sweet smile at breakfast, and his absent-minded politeness. I would have Harry’s passion and Wideacre. And I knew from myself, and from Ralph, that sexuality and Wideacre were the most important things there could be in any person’s life. As crucial as the keystone in the old Norman arch over the gate to the walled garden.

So though I was sure of Harry, the grey area of his feelings for little Celia made me pause before telling him I had conceived an heir. I shut my sunshade with a snap and poked the driver in the back. ‘Drive home,’ I said, ungraciously, and watched him clumsily back the pair into a dusty side road, and turn them for the hotel.

What I needed was some way of giving birth to the child and rearing it in absolute secrecy to give me time to bring Harry around to the idea of a son and heir conceived by me with him. I had to conceal the pregnancy, give birth in secret and find some trustworthy woman to care for the child until I could persuade Harry to produce the little boy before Celia as his son and heir and insist that she care for him.

I nibbled the end of my glove, and watched the vineyards slip past. The peasants were harvesting the grapes along the long rows of gnarled vines. Great, heavy black grapes that make the deep lovely Bordeaux wine. We would drink some this evening at dinner. They drink it young at this time of the year and the taste of it sparkles on your tongue. But there would be little pleasure for me at dinner, or at any other time, if I could not crack this kernel of conflict. First, Harry might simply refuse outright. Or he might agree and then be seized later by a fit of conscience and refuse to force his bastard on Celia. There were bastards in noble households up and down the land, but none that I knew had been imposed on the wife as an heir. Celia, alternatively, might refuse to accept the child, and she would certainly enjoy the support of my mother (not to mention her own family if she told tales). Then everyone would want to know where the baby had come from, and I could not trust Harry’s abilities to sustain deception.

The problem of introducing a bouncing toddler into Wideacre as the new heir seemed insuperable, and while I worried at it a little flame of anger was lit within me again. It seemed that, like me, my son would find his way barred. But like me he would succeed. I should see him at the head of the Wideacre table, and with his foot on Wideacre land, whatever it cost.

In the meantime, I needed some kind, stupid, maternal woman who would care for a newborn baby and prepare him for the life he was to lead, and the place he had to fill. The landaulet stopped and I was handed down in a daydream. I had to find, in this strange land where I spoke not one word of the language, some gentle, stupid, loving woman to rear a cuckoo. I stood, poking the tip of my parasol into the ground at my feet and my sister-in-law, gentle, loving, stupid Celia, came down the steps of the hotel to greet me – and the solution to all my problems broke upon me like autumn sunshine in a thunderstorm.

‘Are you feeling better?’ she asked sweetly. I drew her hand under my arm as we walked up the steps.

‘I am so much better,’ I said, confidentially. ‘And I have something to tell you, Celia, and I need your help. Come to my room and we can talk before dinner.’

‘Of course,’ said Celia, willing and flattered. ‘But what do you need to tell me? You know I will help you in any way I can, Beatrice.’

I smiled lovingly at her, and stepped back gracefully to let her precede me into the hotel. After all, what was one gesture of precedence now, when I should, with her loyal and generous assistance, displace her, and any child of hers, for ever?

As soon as I had shut the door to my bedroom I composed my face into a solemn expression, drew Celia down beside me on a chaise-longue and put my hand in hers. I turned a sad, sweet gaze on her and felt my green cat’s eyes fill with tears as I said, ‘Celia, I am in the most dreadful trouble, and I know not which way to turn.’

Her brown eyes widened and the colour went from her cheeks.

‘I am ruined, Celia,’ I said with a sob, and I buried my face in her neck and felt the shudder that ran through her.

‘I am,’ I said, keeping my face down. ‘Celia, I am with child.’

She gasped and froze. I could feel every muscle in her body tense with shock and horror. Then she determinedly turned my face up so she could look into my eyes.

‘Beatrice, are you sure?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ I said, looking as aghast as she. ‘Yes, I am sure. Oh, Celia! Whatever shall I do?’

Her lips trembled, and she put out her hands to cup my face.

‘Whatever happens,’ she said, ‘I shall be your friend.’

Then we were silent while she digested the news.

‘The baby’s father …?’ she said diffidently.

‘I don’t know,’ I said, choosing the safest lie. ‘Do you remember on the day I rode over to you to fit my gown I was taken ill at Havering Hall?’

Celia nodded, her honest eyes on my face.

‘I felt faint on the ride over and had to dismount; I must have swooned and when I awoke, a gentleman was reviving me. My dress was disordered – you may remember a tear on my collar … but I did not know … I could not tell …’ My voice was a strained whisper, almost silenced by tears and shame. ‘He must have dishonoured me while I was unconscious.’

Celia clasped her hands around mine.

‘Did you know him, Beatrice? Would you recognize him again?’

‘No,’ I said, disposing of the happy ending summarily. ‘I had never seen him before. He was in a travelling curricle with luggage strapped on the back. Perhaps he was driving through Acre on his way to London.’

‘Oh, God,’ said Celia, despairingly. ‘My poor darling.’

A sob stopped her from speaking, and we sat with our arms around each other, our wet cheeks touching. I reflected sourly that only a bride bred on tales from the romances and then raped once and left alone would swallow such a faradiddle. But by the time Celia was experienced enough to doubt conception while unconscious, she would be too well encased in my lie to be able to withdraw.

‘What can we do, Beatrice?’ she said, despairingly.

‘I shall think of something,’ I said bravely. ‘Don’t you grieve now, Celia. Go and change for dinner and we will talk more tomorrow when we have had time to think.’

Celia obediently went. But she paused by the door.

‘Will you tell Harry?’ she asked.

I shook my head slowly. ‘He could not bear the thought of me sullied, Celia. You know how he is. He would hunt for that man, that devil, all around England, and not rest until he had killed him. I hope to find some way to keep this great trouble quite secret, between you and me alone. I put my honour in your hands, Celia, dear.’

She would not need telling twice. She came back into the room and kissed me, to assure me of her discretion. Then finally she took herself off, closing the door behind her as softly as if I was an invalid.

I sat up and smiled at my reflection in the glass of the pretty French-style dressing table. I had never looked better. The changes in my body might have made me feel ill, but had done nothing but good for my looks. My breasts were fuller and more voluptuous, and they pressed against my maiden gowns in a way that filled Harry with perpetual desire. My waist was thicker but still trim. My cheeks flushed with a new warmth, and my eyes shone. Now I was back in control of events I felt well. For now I was not a foolish whore encumbered with a bastard, but a proud woman carrying the future Master of Wideacre.

The following day, as we sat and sewed in the sunny parlour of the hotel, Celia wasted no time in returning to our problem. I was fiddling around, supposedly hemming lace that was to be sent home to Mama on the next packet – though I could not help suspecting she would have to wait a long time if she waited for my hemming. Celia was industriously busy: cutting broderie anglaise from a genuine Bordeaux pattern.

‘I have worried all night, but I could think of only one solution,’ Celia said. I glanced at her quickly. There were dark shadows under her eyes. I could believe she had hardly slept at all for worry at my pregnancy. I had hardly slept either, but that was because Harry had woken me at midnight with hard desire, and then again in the early hours of dawn. We could hardly have enough of each other, and I shuddered with perverse pleasure at the thought of Harry’s seed and Harry’s child inside me at once. And I smiled secretly at the thought of how I had gripped Harry’s hips to prevent him plunging too hard inside me, guarding the child who deserved my protection.

And while I was lovemaking with her husband, Celia, dear Celia, was worrying over me.

‘I can think of only one solution,’ Celia said again. ‘Unless you wish to confide in your mama – and I shall understand if you do not, my dear – then you will need to be away from home for the next few months.’ I nodded. Celia’s quick wits were saving me a lot of troublesome persuasion.

‘I thought’, Celia said tentatively, ‘that if you were to say you were ill and needed my company, then we could go to some quiet town, perhaps by the sea, or perhaps one of the spa towns, and we could find some good woman there to care for you during your confinement, and to take the baby when it is born.’

I nodded, but without much enthusiasm.

‘How kind you are, Celia,’ I said gratefully. ‘Would you really help me so?’

‘Oh, yes,’ she said generously. I noted with amusement that six weeks into marriage and she was ready to deceive and lie to her husband without a second’s hesitation.

‘One thing troubles me in that plan,’ I said. ‘That is the fate of the poor little innocent. I have heard that many of these women are not as kindly as they seem. I have heard that they ill-treat or even murder their charges. And although the child was conceived under such circumstances as to make me hate it, it is innocent, Celia. Think of the poor little thing, perhaps a pretty baby girl, a little English girl, growing up far away from any family or friends, quite alone and unprotected.’

Celia laid down her work with tears in her eyes.

‘Oh, poor child! Yes!’ she said. I knew the thought of a lonely childhood would distress her. It struck chords with her own experience.

‘I can hardly bear to think of my child, your niece, Celia, growing up, perhaps among some rough, unkind people, without a friend in the world,’ I said.

Celia’s tears spilled over. ‘Oh, it seems so wrong that she should not be with us!’ she said impulsively. ‘You are right, Beatrice, she should not be far away. She should be near so we can watch over her well-being. If only there was some way we could place her in the village.’

‘Oh!’ I threw up my hands in convincing horror. ‘In that village! One might as well announce it in the newspapers. If we really wish to care for her, to bring her up as a lady, the only place for her would be at Wideacre. If only we could pretend she was an orphan relation of yours, or something.’

‘Yes,’ said Celia. ‘Except that Mama would know that it was not true …’ She fell silent and I gave her a few minutes to think around the idea. Then I planted the seed of my plan in her worrying little mind.

‘If only it were you expecting a child, Celia!’ I said longingly. ‘Everyone would be so pleased with you, especially Harry! Harry would never trouble you with your … wifely duty … and the child could look forward to the best of lives. If only it were your little girl, Celia …’

She gasped, and I sighed silently with a flood of secret relief and joy. I had done it.

‘Beatrice, I have had such an idea!’ she said, half stammering with excitement. ‘Why don’t we say it is me who is expecting a baby, and then say it is my baby? The little dear can live safely with us, and I shall care for her as if she were my own. No one need ever know that she is not. I should be so happy to have a child to care for and you will be saved! What do you think? Could it work?’

I gasped in amazement at her daring. ‘Celia! What an idea!’ I said, stunned. ‘I suppose it could work. We could stay here until the child is born and then bring her home. We could say she was conceived in Paris and born a month early! But would you really want the poor little thing? Perhaps it would be better to let some old woman take her?’

Celia was emphatic. ‘No. I love babies and I should especially love yours, Beatrice. And when I have children of my own she shall be their playmate, my eldest child and as well loved as my own. And she will never, never know she is not my daughter.’ Her voice quavered on a sob, and I knew she was thinking of her own girlhood as the outsider in the Havering nursery.

‘I am sure we can do it,’ she said. ‘I shall take your child and love her and care for her as if she were my own little baby and no one will ever know she is not.’

I smiled as the great weight lifted from me. Now I could see my way clear.

‘Very well then, I accept,’ I said, and we leaned forward and kissed. Celia put her arms around my neck and her soft brown eyes looked trustingly into my opaque green ones. She wore her honesty, her modesty, her virtue, like a gown of purest silk. Infinitely more clever, more powerful, and more cunning, I met her eyes with a smile as sweet as her own.

‘Now,’ she said excitedly, ‘how shall we do it?’

I insisted that we do nothing, lay no more plans for a week. Celia could not understand the delay but accepted it as the whim of an expectant mother and did not press me. I needed nothing more than breathing space and time to consider my plans. I still had a massive hurdle ahead of me and that was to coach Celia into deceiving Harry. I did not immediately want to set her to the task of lying to the man to whom she had promised loyalty and love, because I knew she would lie extremely badly. The more she and Harry were together, the greater the bond between them grew. They were far from being lovers – however could they be with Celia’s terrified frigidity and Harry’s passionate absorption in me? But their friendship grew warmer and closer every day. I could not be sure of Celia’s ability to lock her real self away from Harry, and I was not sure I could teach her to look her husband in the eye and tell him one bare-faced lie after another.

For myself, I had no doubts. When I lay in Harry’s arms I was his, body and soul. But the possession lasted only as long as the pleasure. As soon as I lay beside him, our bodies green-barred by the hotel shutters closed against the afternoon sun, I was again myself. Even when Harry rolled his head on my hardening, swelling breasts, and exclaimed with delight, I felt no need to tell him that this new beauty was because of the forming of his child. He could see I was happy – anyone could see the glint in my eyes betokened deep secret satisfaction – but I felt no need to confide in Harry that every day brought me closer to an unchallenged place at Wideacre. Through Harry, I had assured myself of a place on the land, but to bear the next Master, and to know that all future Squires would be the blood of my blood and the bone of my bone, was a hard, secret delight.