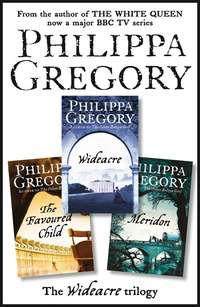

The Complete Wideacre Trilogy: Wideacre, The Favoured Child, Meridon

The moon’s slow pace across the clear sky made a river of light on the floorboards linking Mama and me for the last time. Then I trod lightly down that eerie track and looked at her. She stirred as if she felt my green-eyed gaze on her, but she did not wake. I watched her pale face and heard her rattling, gasping breath, and smiled a gentle smile of certainty. I checked the clock, in another hour she would be ready for her next dose. I would wake Harry.

I slid like a ghost from the room to tap at his door, but it was Celia, not Harry, who opened it.

‘Harry is asleep,’ she said in a whisper. ‘He told me that your mama is ill. Can I come and sit with her?’

I smiled like a woman possessed. It was all coming easily to my hand just as the moonlight had shown me the way to Mama’s bed.

‘Thank you, Celia. Thank you, my dear,’ I said gratefully. ‘I am so weary.’ I had the phial of laudanum in my hand with the little medicine glass. ‘Give her all of this in half an hour’s time,’ I said. ‘John told me exactly what to do before he went back to the library. He said to be sure she takes all of it.’

Celia took the laudanum bottle and nodded her comprehension.

‘I will make sure she does,’ she said. ‘Is John still weary?’

‘He is rested now,’ I said. ‘He was wonderful with Mama, Harry will tell you. And so clear with his instructions!’

Celia nodded. ‘You go and sleep now,’ she said. ‘I will call you if there is any change, but you need your rest, Beatrice. Go and sleep now, and I will give her the laudanum just as John directed.’

I nodded my acquiescence and left Celia at Mama’s door. I went soft-footed down the stairs. I paused outside the library door to hear a stertorous breath. I pushed the door open cautiously, and went in.

Daylight was making the windows shady grey and I could just make out the wreck of the man who had once been proud to love me. He was still in his chair, but he had vomited, staining his plum travelling jacket and his riding breeches. At some time he had smashed his glass on the stone fireplace and instead drunk from the bottle, for it was almost drained dry. It had at last put him soundly to sleep. His medical bag was tumbled on the floor beside him, the pills and the little bottles spilling out of its open mouth.

Keeping my eyes fixed on his sprawled, sodden, stained body I held my skirts outwards and stepped backwards, slowly, slowly and silently, until I could close the door and turn the key to lock him in. I wanted no loyal housemaid or young footman cleaning up Miss Beatrice’s young husband before she saw him, to spare her pain.

Then, my silken evening gown whispering around me, I glided through the connecting door to the west wing, to my room.

My maid was long since abed, for I encourage no one to wait up for me past midnight. So I shifted for myself and slid out of my gown and sweaty petticoats. Half a lifetime ago, these had been pulled to my waist to enable me to couple with Harry. Now they seemed soiled in the ancient past, and I left them: gown, stays, petticoat, stockings and all, in a heap on the dressing-room floor.

From my cupboard I chose a light morning wrapper, as pink and promising as the rising sun, which I could see warming the rose garden. It was going to be a hot day. It was going to be a long hard day, and I would need my wits about me. The water in the ewer was cold, of course, but I splashed it on my face and all over my shivering body. Of all the people in this sleeping house I would need to be the most awake, the most alive. This day would be a trial in which my claim to Wideacre could turn on the flip of a coin. I would neglect nothing that would make me more alert, or stronger.

I slid on the cold silk wrapper, wrapped a shawl around my shoulders, and settled in my chair to wait. It must have been about an hour since I had left Celia, but I was too wary to creep back to the main part of the house to listen. I was wise enough, and controlled enough, to sit with my feet resting on a little stool, and wait for events to turn the way I had ordered. Then I heard a door bang, and the library door rattle, and Celia’s voice sharp with fear calling for my husband.

‘John! John! Wake up!’

I heard her bang the door to the west wing and I tore open my bedroom door to greet her on the stairs as if I had leaped from my bed on hearing her call.

‘What is it?’ I demanded.

‘It is Mama,’ she said desperately. ‘I gave her the laudanum as you said, and she seemed to fall asleep. But now she seems too cold, and I cannot find her pulse.’

I held out my hands to her, and she gripped them hard, her face absurdly young and anxious, then we turned and fled down the stairs together.

‘John?’ I asked her.

‘I cannot wake him, and he seems to have locked himself in,’ she said, despairingly.

‘I have a spare key,’ I said, and opened the door and flung it wide so Celia could see the chaos.

The morning light picked out the stains on John’s clothes and the splashes of vomit on the stone fireplace and on the priceless rugs. In his doze he had knocked over the final bottle and his head lay in a pool of sour-smelling whisky. The chair was kicked over, and there was manure from his boots on the window-seat cushions. My husband, the light of the healing profession, lay like a dog in his vomit, unstirring even when we erupted into the room calling his name.

I strode over to the bell and rang a loud peal, and then picked up a jug of water and threw it into his face. He rolled his head in the wet and groaned. From the servants’ quarters I heard a clatter of pans and hurrying footsteps, and from above I heard Harry pattering barefoot down the corridor and down the stairs. He and the scullery maid arrived together.

‘Mama is worse, and John is drunk,’ I said to Harry, conscious that every word would be relayed to Acre village and far beyond by the girl.

‘Go to Mama,’ Harry said authoritatively. ‘I’ll wake John.’ He bent over my husband, and hauled him into a chair. ‘A bucket of cold water,’ he said to the girl, ‘fresh from the kitchen pump, and a couple of pints of mustard and warm water too.’

‘Then wake the stable lads and Stride,’ I said to her as I went towards the stairs. ‘Tell one of the lads to ride to Chichester. We need a competent doctor.’

I ignored Celia’s gasp and went up to Mama.

She was dead, as I knew she would be.

She had not suffered, and I was glad of that, for Papa’s death had been hard and brutish, and Ralph had a long vigil of agony. But this last and, I hoped, final death for Wideacre had been easy drugged sleep. She was lying on her rich, lacy pillows in her fancy new white and gold bed. The drug had seen her on her way smiling at pleasant visions. Under the massive overdose given her by the loving hands of her sweet daughter-in-law she had slid away from the nightmare truth of our lives into a palace of hallucination where nothing could ever disturb her again.

I kneeled at the bedside and put my forehead to her hand, and shed a few easy tears on the embroidered sheet.

‘She is gone,’ said Celia, and she knew there was no doubt.

‘Oh, yes,’ I said softly. ‘But so peacefully, Celia, I have to be happy she went in such peace.’

‘Although I ran for you and for John, I knew it was too late,’ said Celia quietly. ‘She was just like this then. I think she must have died as soon as I gave her the medicine.’

‘John said her heart might not survive it,’ I said. I rose to my feet and mechanically straightened the smooth covers, and then went to open the window and draw the curtains. ‘But I wish to God he had sat with her.’

‘Don’t blame him, Beatrice,’ said Celia, instantly tender. ‘He had a long hard journey. He could not have anticipated that your mama would become ill so suddenly. He had been all this time away, and we have been with her every day and noticed nothing. Don’t blame him.’

‘No.’ I turned from the window back into the shaded room. ‘No. No one is to blame. We all knew Mama’s heart was delicate. I do not blame John.’

Around us were all the noises of Wideacre awakening, yet curiously hushed, as the servants scurried to prepare the house and pass the news among each other in shocked whispers. Celia and I closed Mama’s door, and went down to the parlour.

‘Coffee for you,’ said Celia tenderly, and rang the bell. As we sat in the parlour I could hear the heavy tread of Harry walking John up and down the library floor, marching him into consciousness. And then a muffled sound of choking as he forced the mustard and water down John’s throat, and then a horrid retching noise as John vomited on the emetic and brought up neat whisky. Celia grimaced and we moved to the window seat where we could hear the morning birdsong instead.

It was a perfect, breathless morning with the smell of the roses and the meadows hanging on the warm air like a message of renewal. The fresh leaves of the beeches, still silvered with dew, shimmered in the wood, and in the valleys that intersect the green horizon of the downs the mist was rolling like pale gauze. It was a land worth anything, any price. And I linked my fingers around my cup of coffee with conscious justification, and drank deep of the scalding liquid.

The parlour door opened, and Harry came in. He looked white and stunned, but better than I had hoped. At least he did not look guilty – which was what I had feared. He held out a hand speechlessly to Celia and she ran into his arms.

‘John is himself again,’ he said to me over Celia’s head. ‘He could have chosen a better time to drink, but he is sober now.’

Celia disengaged herself, and poured him a cup of coffee. Harry dropped into his chair by the hearth, where the embers of last night’s fire still smouldered.

‘I have seen her,’ he said briefly. ‘She looks very peaceful.’

‘She was,’ Celia assured him. ‘She said nothing. She just smiled, and fell asleep.’

‘You were with her?’ he said surprised. ‘I thought it was Beatrice?’

‘No,’ said Celia, and I lowered my eyelids to hide the gleam of satisfaction at my magical luck. ‘Beatrice went to bed after she woke me. I was with your mama when she died.’

I raised my eyes and saw John standing in the doorway listening. He had thrown a dressing-gown over his soiled linen and his face and hair were clean and wet from the soaking Harry had given him. He looked alert and awake. I tensed like a rabbit scenting a stoat.

‘She had no more than the proper dose?’ he said. His speech was still slurred and his head was weaving like a fighter who has suffered too many blows to the head.

‘As you ordered,’ I said. ‘Celia did as you said.’

‘Celia?’ he said. His pale eyes squinted against the bright sunlight. He put up one dirty hand to shield his face from the bright light of the Wideacre sun. ‘I thought it was you who was there, last night.’

‘Get to bed, man,’ said Harry coldly. ‘You’re still half foxed. You left Beatrice and me to nurse her, then Celia took my place. You yourself were little help.’

John stumbled to a chair near the door and stared at the floor.

‘Four drops,’ he said eventually. ‘Four drops, four-hourly; that should not have been too much.’

‘I don’t know in the least what you’re talking about,’ I said, and my voice was like a sharp stone skimmed over a frozen river. ‘You gave me a phial and told me to give it to her. Celia did so, and then she died. Are you telling us now you made a mistake?’

John squinted at me through his sandy lashes as if he was trying to see something in his memory that had escaped him.

‘I don’t make mistakes with medicines,’ he said flatly, holding on to that one certainty.

‘Then no mistake was made,’ said Harry impatiently. ‘And now get to bed. Mama has just died. You should show some respect.’

‘Sorry,’ said John inadequately. He stumbled as he rose to his feet. Harry, resigned, went to support him and nodded me to his other arm.

‘Don’t you two touch me!’ he exclaimed, and he spun on his heel for the door. The swift movement was too much for his spinning head and his knees buckled. He would have fallen but Harry grabbed him and I went unwillingly to hold his other arm. We marched him, sagging between us, up the stairs to the west wing and slung him on to his bed.

I turned to go but John grabbed at my wrist with sudden strength.

‘Four drops I said, didn’t I, Beatrice?’ he whispered. His eyes were suddenly bright with comprehension. ‘But I know too what she was talking about. What she had seen. What she found when she came for her novel. Beatrice and Harry. I told you four drops, but you told Celia the whole phial, didn’t you?’

I could feel the delicate bones in my hand starting to crack, but I made no effort to free myself. I had been readying for this since dawn and he could break my arm, but he could not defeat me. It hurt me still to lie so bold-faced, to the only other man who had loved me honestly, but I gave him look for look and my eyes were like green ice. Energy coursed through me for I was fighting for Wideacre. Against me, he was weak, just a drunk dreaming a nightmare.

‘You were drunk,’ I said bitingly. ‘So drunk you could not choose the medicine. You spilled your medical bag all over the library floor. Celia saw it this morning; the servants have seen it. You did not know what you were doing. You did not know what you were saying. I trusted you because I believed you were a great doctor, a truly great physician. But you were too drunk even to see her. If she had an overdose of laudanum it was you who put the drug in my hands and told me to give it to her. If she died because you gave her too much, then you are a murderer and should be hanged.’

He dropped my wrist as if it had scorched him.

‘Four drops, four-hourly,’ he panted. ‘I would have told you that.’

‘You remember nothing,’ I said with utter conviction, with utter contempt. ‘But what you should remember now, now you are sober, is that if there is any murmur of a question, any whisper of a question, about Mama’s death, it needs only one word from me and you will hang.’

His pale eyes were wide with abhorrence and he gazed up at me from the pillow of the big bed as if I smelled of sulphur from the very depths of hell.

‘You are wrong,’ he whispered. ‘I do remember; at least I think I remember it all. It is like a nightmare, so infamous I cannot believe it. But I do remember it, like a dream in delirium.’

‘Oh, fustian!’ I said, suddenly impatient. And I turned to leave. ‘I’ll send you up another bottle of whisky,’ I said with disdain. ‘You seem to need one again.’

And then I wavered.

All the time while I prepared for Mama’s funeral, arranged the ceremony, invited the guests, discussed the dinner menu with Celia and organized the servants into black trimmings, I wavered. In the week before Mama’s funeral my hand was on the doorknob to John’s bedroom, I think, once a day. I had learned to love him so recently; I loved him still, in some small corner of my lying heart, so very much.

But then I would pause and think what he knew about me. I would think with a shudder what would become of me if he spread his foul talk into Celia’s ears. If she and he together speculated about the father of Julia. And then my hand would drop from his door and I would turn away, my face hard, my eyes stony. He had seen into the depths of my crime. I saw a reflection of myself in his pale eyes that I could not bear. He knew the humiliating evil price I had paid to make myself secure on Wideacre and before him I was not just exposed and vulnerable. I was shamed.

So in all the bustle and confusion to plan and execute a respectable Wideacre funeral I did not forget to order Stride to take a fresh bottle of whisky up to Dr MacAndrew’s bedroom and study every midday and dinnertime. Stride’s eyes met mine with unspoken sympathy, and I managed a wobbly smile for him. ‘Pluck to the backbone’ was the verdict on me in the servants’ quarters, and although John had prompt service to his ring for a fresh glass, or more water to take with his drink, he was despised in the servants’ hall.

The rumour that his incompetence had caused Mama’s death had spread through the Hall and beyond to Acre village, and for miles around. It had reached the ears of the Quality through a thousand tattling maids and valets. When John wished to return to the normal world of visits and parties and dinners he would find doors closed against him. There would be no entry for him into the only world he knew unless I reintroduced him with all my charm and power.

He was not even summoned as a doctor to the yeoman farmers’ homes or to the Chichester and Midhurst tradesmen. Even the families of the middling sort had heard the gossip and there would be black looks for him in every village for a hundred miles around: for his drunken incompetence with Lady Lacey, and for grieving Miss Beatrice, the darling of the county.

My grief for a few days was real indeed. But as my fear of him and my sense of shame about his knowledge grew, I found I became colder and colder towards him. By the day of Mama’s funeral, only one week after I had threatened him with a hanging if he tried to betray me, I knew I hated him, and I would not rest until he was off Wideacre and silenced for good.

I had hoped he would be drunk on the day of the funeral, but as Harry handed me into the carriage John came out of the front door into the bright June sunlight. He was meticulously dressed in a neatly cut suit of black, his hair perfectly powdered, his black tricorn trimmed with black ribbon. He was pale, pale and cold, despite the hot sun. Or at least he shivered when his eyes met mine. But he had taken no more than he needed to face the day, and to judge from the hardness in his eyes, he was determined to see it through. Beside him, Harry looked plump and bloated and self-indulgent. John came towards the carriage steady-paced like some white-faced avenging angel, and stepped in to seat himself opposite me, without a word to any of us. I felt a touch of fear on my heart. John drunk was a public humiliation for me, his wife. But John sober and vengeful could ruin me. He would have every legal right to order and control me. He could legally watch my every movement. He would know if my bed had been slept in. He had a legal right to come into my room, into my bed, at any time, day or night. Worse, and even more unbearable – I clasped my black-gloved fingers in my lap to keep them from trembling – he could move away from Wideacre and sue me for public divorce if I refused to go with him.

In stealing his name for my fatherless child I had also robbed myself of the freedom any man, married or single, could take for granted. Both my days and nights had to be lived under the supervision of this man, my husband, my enemy. And if he wished he could imprison me, beat me, or take me from my home with the full blessing of the law of the land. I had lost even the limited privilege of my spinsterhood. I was a wife – and if my husband hated me, then I faced the certainty of a miserable future.

He leaned forward and patted Celia’s little hands clasped over her prayerbook.

‘Do not be too sad,’ he said tenderly. His voice was hoarse from the lack of sleep and the continual drinking. ‘She died a peaceful, easy death, and while she lived she had great happiness in your company and with little Julia. So do not be too sad. We could all hope for a blameless life of love as she had, and a peaceful, easy death.’

Celia bowed her head and her black-gloved hand returned John’s touch.

‘Yes, you are right,’ she said, her voice low with the effort of controlling her tears. ‘But it is a sad loss for me. Although she was only my mama-in-law I felt I loved her as much as if I had been her daughter.’

I felt John’s hard, ironic gaze on my face at this artless confession from Celia. Behind my veil my cheeks burned with rage at him, and at this whole sentimental conversation.

‘Just as much,’ John agreed, his eyes still hard on me. ‘I am sure Beatrice thinks so too, don’t you, Beatrice?’

I struggled to find a tone of voice that was free from either the rage or the fear I felt at this deliberate baiting of me. He was sliding like a clever skater on the thin ice of the truth. He was daring me; he was frightening me. But I had some power too, and he had best remember it.

‘Yes, indeed,’ I said levelly. ‘Mama always said that she was so lucky in the choices that Harry and I made. Such a lovely daughter-in-law, and so fine a doctor for a son-in-law.’

That hit him, as I had known it would. One word from me and his university would scratch his name from their records. One word from me and it would be the hangman’s noose for him and not all his clever spite could save him. He had best remember that, if he drove me to it, I would face down the scandal and the gossip that an accusation of murder would cause, and I would publicly claim that he overdosed Mama while he was drunk. And no one could gainsay me.

He sat back in the carriage beside Harry, careful not to let any part of his coat touch him. And I saw how he bit his lips to keep them from trembling, and clasped his hands to keep them still. He needed a drink to keep his private world of horrors at bay.

All four of us gazed dumbly out of the windows as the tall trees of the drive slid past, and then the fields, and then the little cottages of Acre village. The funeral bell was tolling, one resounding stroke after another, and in the fields I saw the day labourers pulling off their hats and standing still as we drove by. As soon as the carriage was past they set to work again and I was sorry for the old days when every man on the estate would have had a day’s paid holiday to pay his respects to the passing of one of the gentry. But the tenants, even the very poorest of cottagers, had given up a morning’s work to crowd into the church to be present at Mama’s funeral.

She was all there was left of the old Squire, my papa, and with her sudden, unexpected death, the land and the house now belonged to the young generation. There were plenty in the church and in the graveyard to say that Mama’s death was the passing of the old days and old ways. But there were even more who said that my papa lived on while I ruled. That on Wideacre at least there was no need to fear change and an uncertain future, for the real power at Wideacre did not rest with the Squire who, gentry-like, was mad for change and profit, but was with the Squire’s sister, who knew the land like most ladies know their own parlour, and was more at ease in a meadow than a ballroom.

We followed the coffin into church for the heavy, ominous service, and then we followed it out again. They had opened the Wideacre vault and Mama was placed next to Papa, as if they had been a loving, inseparable couple. Later on, Harry and I would erect some sort of monument to her beside the marble monstrosity already in place on the north wall dedicated to Papa. The Vicar, Pearce, reached the end of the service and closed the book. For a moment I forgot where I was, and I threw up my head like a pointer scenting the wind, and said, with a landowner’s fear in my voice, ‘I can smell burning.’

Harry shook hands with the Vicar, and nodded to the sexton to close the vault. Then he turned to me.

‘I don’t think you can, Beatrice,’ he said. ‘No one would be burning stubble or heather at this time of year. And it is too early for accidental wood fires.’

‘I can,’ I insisted. ‘I can smell burning.’ I strained my eyes in the direction of the west wind. A glow on the horizon, little larger than a pin head, caught my eye.

‘There,’ I said pointing. ‘What’s that?’

Harry’s eyes followed the direction of my finger and said in doltish surprise, ‘Looks like you are right, Beatrice. It is a fire! I wonder what it can be? It looks like quite a wide area – too big for a barn or a house fire.’

Other people had heard me say, ‘There’ and had seen the ominous redness on the skyline – pale in the sunlight but bright enough to be seen all these miles away. I listened to the murmur and I was quick – perhaps too quick – to identify something more than the usual country curiosity. The cottagers behind me had a tone almost of satisfaction in the low gossiping voices. ‘It’s the Culler,’ they said. ‘The Culler promised he would come. He promised it would be this day. He said it would be seen from Acre churchyard. The Culler is here.’