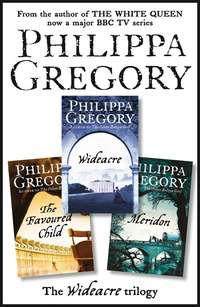

The Complete Wideacre Trilogy: Wideacre, The Favoured Child, Meridon

I turned sharply, but the group of closed faces revealed nothing. Then there was a clatter of hoofs and a sweating shire-horse came thundering down Acre street, still harnessed for work, with a little lad bouncing like a cork on its broad bare back.

‘Papa! It’s the Culler!’ he called in ringing tones which brought the murmur to silence.

‘They’ve fired Mr Briggs’s new plantation, Papa! Where he enclosed the old common land and drove the cottagers off. Where he planted his five thousand trees. The Culler has fired the new wood, and there will be nothing left but blackened twigs. Mama told me to come and fetch you at once. But the fire will not touch us.’

His papa was Bill Cooper, indebted to us for a mortgage for his farm, but an independent man, not a tenant. He felt my eyes upon him and sketched a bow in farewell and strode towards the churchyard gate. I hurried after him.

‘Who is this Culler?’ I asked urgently.

‘He’s the leader of one of the worst gangs of bread rioters and corn rioters and arsonists the county has ever seen,’ Bill Cooper said, leading the horse to the lychgate for easy mounting. Forgetful of my new black silks I held the horse’s head while he climbed the gate and heaved himself up on to the broad back, behind his son. ‘The leader is nicknamed the Culler because he says gentry stock is rotten and should be culled.’

He looked down at me and saw my eyes darken and mistook my fear for anger. ‘Begging your pardon, Miss Beatrice – Mrs MacAndrew, I should say. I am only telling you what my labourers told me.’

‘Why have I not heard of him?’ I asked, my hand still on the reins.

‘He is only lately come into Sussex from another county,’ said Bill Cooper. ‘I only heard of him myself yesterday. I heard Mr Briggs had a note nailed to one of his fine new trees. It warned him that landlords who put trees before men have no right to the land – that the cull of the landlords is starting.’

He tightened the reins and kicked the horse forward. I could feel Harry, Celia and John all staring at my back in astonishment, as I clung to the reins and barred the way. But I had no time for conventions. I was driven by a fear I needed to lay at rest then and there on that sunlit Saturday morning.

‘Wait, Cooper,’ I said peremptorily. ‘What sort of a man is he supposed to be?’ I asked. I kept the horse from moving on with a hard hand on the bit, and kept my satin shoes well away from its heavy, shifting feet.

‘They say he rides a great black horse,’ said Bill Cooper. ‘They say he used to be a keeper on an estate, that he learned the ways of the gentry then, and started to hate them. They say his gang would follow him to hell. They say he has two black dogs which go with him everywhere like shadows. They say he is a legless man; he sits oddly on his horse. They say he is Death himself. Miss Beatrice, I must go … he is near my land.’

I loosed him. My hand fell powerless from the bridle and the horse brushed past me so close I had the sting of its coarse tail in my face. I knew him, the Culler. I knew him. And the glow of his fire was on Wideacre’s horizon. I swayed, my eyes on the unnatural glow, and my lungs, hair and clothes full of the smell of his smoke.

Celia was at my side.

‘Beatrice are you unwell?’ she asked.

‘Get me to the carriage,’ I said, miserably. ‘I need to be home. I want to be through the lodge gates and behind the front door and in my bedroom. Get me home, Celia. Please.’

So they said I was too distressed at the loss of Mama to shake hands with all the mourners at her funeral, and the kindly respectful faces lined the lane as our carriage drove off. Surely there was no one here who would hide or shelter a gang of desperate men, enemies to the peace of the land? I reassured myself. Not one of my people, not one of them would hide the Culler on Wideacre land. Whatever their private mysterious loyalties and codes of peasant honour, they would surely turn a criminal like the Culler over to a Justice of the Peace if ever he came near my sweet peaceful boundaries. He might burn up to the very parish bounds, hidden and helped by people glad to see their masters humiliated, but on Wideacre I held hearts as well as wealth in my hands. While I was loved the Culler had no chance. Not even if he was Wideacre-born and bred himself. Not even if he had known and loved Wideacre as well as I.

A sob of fear escaped me, and Celia’s arm came round my shoulders and held me tight.

‘You are tired,’ she said tenderly. ‘You are tired, and there is no need for you to do any more work for today. You need not take dinner with the guests. You have worked so hard with all the planning and work for this day. There is no need for you to do anything more but rest, my dear.’

Indeed, I was weary. Indeed, I was horribly afraid. My bright, brave relentless courage and anger seemed all burned up like Mr Briggs’s woods, leaving nothing but black and smoky ground where no birds sing. With the Culler’s work making an ominous grey smudge on the horizon there would be neither rest nor peace for me until he was taken. My head dropped to Celia’s shoulder and she patted my back. Under my lashes, behind my veil, I stole a swift glance at my husband, sitting opposite me. He was scanning my pale face as if to read the very depths of my soul. Our eyes met, and I read his sharp, trained, professional curiosity. I shivered uncontrollably in the bright sunlight. The day, which had started so bright and with such a promise of heat, was clouding over and grey thunderclouds blurred with the smoke on the horizon. With the Culler less than a hundred miles from my home and John MacAndrew in my bed, I was endangered indeed.

And the stimulus of my fear, my collapse, was acting on John like a dram of whisky. His own horror was forgotten when he saw the look on my face, when he saw my terror. At once his clever, analytical brain shook free from nightmare, shook free of drink.

He suddenly leaned forward.

‘Who is this Culler?’ he asked, his speech clear. ‘What is he to you?’

I shuddered again, uncontrollably, and turned my face in to Celia’s warm shoulder. Her hand tightened comfortingly around me.

‘Not now,’ she said gently to John. ‘Don’t ask her now.’

‘Now is the only time we might hear the truth!’ said John brutally. ‘Who is the Culler, Beatrice? Why do you fear him so?’

‘Get me home, Celia,’ I said, my voice a thread. ‘Get me to bed.’

When the carriage drew up to the steps I let Celia lead me to my bedroom and tuck me up in bed as if I were a feverish child. I took two drops of laudanum to keep the clank of the mantrap, the clatter of a falling horse, and the sad soft sigh of my mama’s last breath out of my dreams. Then I slept like a baby until suppertime.

The will had been read in the afternoon, and most of the mourners had dispersed, concealing their pleasure or disappointment at the little bequests as well as they could. Mama’s small capital was divided equally between Harry and me. She never owned any land, of course. The earth beneath her feet, the rocks beneath the earth, the trees above her head and even the birds that roosted in them never belonged to her. In her girlhood she had lived in her father’s house. In her womanhood she had lived in her husband’s home, on his land. She never earned a penny, she never owned a farthing that she could in truth call her very own. All the money she left was no more hers than the jewels she had passed on to Celia when Celia married Harry. All she had ever been to Wideacre, to the bank account, to the jewels, to the house, to the land, was a tenant.

And all landlords despise their tenants.

But her rich poverty made the will a simple matter and the reading was over and done by teatime. By the time I emerged for supper at nine o’clock there were only John and Harry and Celia and I to dine with Dr Pearce, the Acre Vicar.

It was the first time that John had been in company since his return home and the night of Mama’s death, and for once I blessed Harry’s doltish insensitivity to other people’s feelings and to the tension in the room. Though slightly subdued by the day, he chatted loudly and easily to Dr Pearce as the three stood before the library fire. No one who looked at Harry, tumbler of sherry in hand, warming his breeches before the fire, would be able to believe that he had ever dragged John out of a stupor of alcohol in this room. Or that he had ever thrown his sister on the hearth and taken her with passionate desperation. But, to judge from John’s tense shoulders and scowl, he could imagine both events. Celia remembered his drinking bout too, and I saw her brown eyes anxiously straying to John’s face and to the glass in his hand. He turned aside from the window to smile down at her with a suddenly lightened face.

‘Do not look so anxious, Celia. I shall not break the furniture.’

Celia blushed rosily, but her loving brown eyes met his directly. Anyone looking at her could have seen her honest affection for him, her concern for his health.

‘I cannot help being anxious for you,’ she said. ‘It has been a most difficult time. I am glad you feel able to be with us today. But if you should change your mind and wish to dine alone in your room I should be happy to order a tray for you.’

John nodded his thanks. ‘That is thoughtful of you, Celia, but I have been enough alone,’ he said. ‘My wife will need my company and support, you know, in the days and weeks ahead.’ He said ‘my wife’ as one might say ‘my disease’ or ‘my snake’. His sarcastic voice was hard with detestation when he looked at me. No one, not even little loving Celia, could have mistaken his meaning, and thought his pretended concern sincere. Even Harry paused and glanced curiously at the three of us. John standing, his back to the room; Celia, her sewing falling unnoticed, looking up at him, her colour fading; and I, bent over the round table in the centre of the room, affecting to turn the pages of the newspaper, but as tense as a whip. John turned to the decanter and poured himself another full glass. He tossed it off as if it were medicine.

Then Stride announced supper and broke up the scene, and I enjoyed a small revenge, walking past John, so close that my train swept his legs, to claim Harry’s hand to lead me in to supper. Harry sat at the head of the table; I took the foot: Mama’s old place. Celia sat where she had been placed since her marriage, on Harry’s right, and John sat beside her with Dr Pearce opposite them. John’s nearness to me made me icy with affront, but I could tell it sickened him.

He made an effort at distant cold courtesy with Harry, but he could not bear to be physically near him. If Harry’s hand brushed his sleeve in passing John shrank as if from an infection. Harry disgusted him, and he loathed me. His hatred expressed itself in direct malice, in biting sarcasm, in concealed insult. All I could do against him was to torment him with my nearness, which reminded him of his past desire for me. He scarcely touched his food and I wondered, with malicious pleasure, how long his use of alcohol would be controlled under the twin pressures of his rage and enforced silence. He had a glass of wine, nearly untouched, at his place and I nodded to the footman to refill it.

Dr Pearce was a newcomer and sensed a little of the tension of this family party. But he was a man of the world and with interest and courtesy he encouraged Harry to talk about his farming experiments. Harry was proud of the changes taking place on our land, and the wealthier tenants were following his lead and making Wideacre known as a pioneer of the new techniques. I had my reservations, and my love of the old ways, and the reputation that Miss Beatrice held by the traditions and spoke for the poor did me no harm with the people on the land.

‘When I started farming at Wideacre there were barely two day labourers on the place, and we used ploughs which were unchanged from Roman times,’ Harry said, on his hobby-horse again. ‘Now we have ploughs that can cut a furrow nearly up to the top of the downs and there are fewer and fewer squatters and cottagers on Acre.’

‘Small benefit to us all,’ I said drily from the other end of the table. I noted how John tensed at the very sound of my cool, silvery voice and reached unconsciously for his wine glass.

‘The cottagers who used to live in the hovels around the village have now become day labourers or even live in the parish workhouse and work in the workhouse gangs. And your new plough has ripped up old, good meadows to make surplus cornfields, which will create year after year of corn glut. The price of bread tumbles; the corn is hardly worth selling for years in a row, and then in the first bad year there is uproar because the price suddenly soars.’

Harry smiled down the table at me.

‘You are an old Tory, Beatrice,’ he said. ‘You hate all change and yet it is you who keep the books. You know as well as I do what the wheatfields pay.’

‘They pay us,’ I said. ‘They profit the gentry. But they do little good for the people on Wideacre. And they have done no good at all for those we used to call our people – the ones who lived in the hovels we cleared away and kept their pigs on the common patch we have now enclosed.’

‘Ah, Beatrice,’ said Harry, teasingly. ‘You speak with two voices. When the books show a profit you are pleased, and yet in your heart you prefer the old wasteful ways.’

I smiled back, forgetting John, forgetting the tension, my mind on Wideacre. Harry’s was a fair comment. Our disagreement was as old as our joint management of the land. If I ever thought Harry’s new methods were a real danger to the peace and prosperity of Wideacre then I would stop him in the same second. And there had been plans of his that I had vetoed and we had heard no more of them. What concerned me, as one of the handful of gentry among the millions of poor, was that Harry’s schemes and the trend of the whole country were to profit the gentry more and more and to make the poor yet poorer.

‘It is true,’ I said smiling at Harry with a softness in my voice and a tender light in my eyes for my land. ‘I am but a sentimental farmer.’

John’s chair scraped harshly on the polished floor as he thrust it back abruptly.

‘Excuse me,’ he said, pointedly ignoring me, speaking only to Celia. He walked heavily towards the door and shut it with a firm click as if to emphasize his rejection of us, and the candlelit room. Celia looked anxiously at me, but my face never wavered. I turned to Dr Pearce as if there had been no interruption.

‘But you come from the higher, colder north where I think there is little wheat grown at all,’ I said. ‘You must find our obsession with the price of wheat and white flour odd.’

‘It is very different,’ he admitted. ‘In my county, Durham, the poor still eat rye bread; black or brown bread, it is. Nasty stuff compared to your golden loaves, I admit, but they fare well on it and it is cheap too. They eat a lot of potatoes and pastry dishes made with the coarse flour as well, so the price of wheat matters far less. Here I think the poor are wholly dependent on wheat?’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Celia in her soft voice. ‘It is as Beatrice says. It is well enough when the price of corn is low, but when it rises there is real hardship, for there is no alternative food.’

‘Then the damned fools riot,’ said Harry, with two-bottle bluster. “They riot as if we can help the rain spoiling the crop and making it too dear for them to buy.’

‘It’s not all chance,’ I said reasonably. ‘We do not profiteer and we do not hoard at Wideacre, but there have been some wicked fortunes made by withholding corn from the market, and by sending it out of the county. When merchants deliberately create a shortage they know full well that there will be hunger and then disturbances.’

‘If they would only go back to eating black bread!’ sighed Celia.

‘These are my customers!’ said Harry, laughing. ‘I would rather they stuck to white bread and went hungry in the lean years. The day will come when we have more and more land growing wheat and the whole country eats nothing but white flour.’

‘If you can grow it, and I say “if”, Harry, then good luck to you,’ I said. ‘But while I keep the books we will plant no more wheatfields. I believe the bottom will fall out of the market. It is all very well one farmer planting wheat, but every single Squire up and down the country is doing so. Come a bad year and there will be many wheat farms ruined. Wideacre will never be a one-crop estate.’

Harry nodded. ‘Aye, Beatrice,’ he said. ‘You are the planner. And we should not be boring Dr Pearce and Celia with this farming talk.’

He sat back in his chair and at a nod from me the servants cleared the plates. Dr Pearce and Harry chose cheeses from the board, and the great silver fruit bowl, piled high with our own produce, was placed in the middle of the table.

‘One would be foolish indeed to be bored with such work that produces such wonderful results,’ said Dr Pearce politely. ‘You eat like pagans in a golden age at Wideacre.’

‘I am afraid we are pagan,’ I said lightly. I took one of the plump peaches and peeled its downy skin to eat the sweet slimy fruit. ‘The earth is so good, and the yields are so high, that at harvest time I find it hard not to believe in magic,’

‘Well, I believe in science,’ said Harry staunchly. ‘And Beatrice’s magic goes well with my experiments. But, Dr Pearce, you would burn my sister for a witch if you ever saw her in a hayfield!’

Celia laughed. ‘It is true, Beatrice. Only the other day you were supposed to be taking Sea Fern to be shod and I saw him tied to the gate of Oak Tree Meadow and you in the middle of the field, with your hat off and your face tilted up to the sky with handfuls of poppies and larkspur in either hand. I was driving into Chichester with Mama and I had to point something out to her to distract her attention away from you. You looked like Ceres in a mummers’ play!’

I laughed ruefully. ‘I see I shall become a well-known eccentric and be jeered at by the apprentices in Chichester!’ I said.

‘Even I had not long arrived in Acre before I heard strange and ominous rumours,’ said Dr Pearce, twinkling at me. ‘One of your older cottagers, Mrs MacAndrew, told me that he always asks you to take tea and walk in the fields at sowing time. He swore it is a sure way to ward off rust mould on the seeds to have Miss Beatrice take a few steps behind the plough.’

I nodded at Harry. ‘Tyacke, and Frosterly and Jameson,’ I said certainly. ‘A few others like to believe it too. I think a couple of good seasons coincided with the time when I was first out on the land alone after my papa’s death, and that convinced them.’

A secret stab of nostalgia touched me at the memory of those good seasons. The first summer of my womanhood when I had met and loved with Ralph under the blue sky of a summer that seemed never-ending, and the second summer when Harry had been the Lord of the Harvest and brought in the corn like a Summer King. Then there was the third hot year and my third good lover, John, who had courted me, and kissed my hand and driven me miles around the estate on one sweet unlikely pretext after another.

‘Magic and science,’ said Dr Pearce. ‘No wonder your crops flourish.’

‘I hope it lasts,’ I said, without knowing what made me cast such a shadow over the conversation. A flicker of some premonition – as insubstantial and yet as ominous as woodsmoke on a distant horizon – touched me. ‘There is nothing worse than a bad year after a series of good ones. People become too confident, they expect too much.’

‘They do indeed,’ said Dr Pearce quickly, confirming Harry’s view of him as a hard-headed realist, and my view of him as an unimaginative, pompous man. I knew too well what would follow: a tirade against the poor, their unreliability with rent and tithes, their ceaseless fertility, their unreasonable demands. If Celia and I withdrew now, there was a chance that Harry and Dr Pearce would have finished by the time they came to the parlour for tea. I nodded at Celia, and she left some grapes on her plate and rose with me. Stride went to the door, but Harry put him aside with a gesture and held the door for us both. I let Celia precede me and knew I had read the gesture aright when I saw Harry’s warm eyes on me. The talk of the land had reminded him of my power and my beauty. He had buried his horror and fright with his mama, and tonight we would be lovers again.

It was easier to meet him than I had dared to imagine. John’s abrupt departure from the dinner table had signalled, as I had hoped, a return to hard drinking. I had hardly aided his resolution against alcohol, for when he had flung himself into his study in the west wing he had found the dew forming on two icy-fresh bottles of whisky, a pitcher of cool water to mix with a dram, and a plate of biscuits and cheese to bolster the illusion that he was merely taking a small glass with a meal. Casually, as if blind to his own hands, he had broken the seal on one of the bottles and poured a measure, the merest drop, and diluted it well. One taste undid his resolve and he had drunk nearly all of one bottle by the time I came, clear-headed, to peep in on him. He was asleep in his chair by the log fire. The smartness of his early-morning appearance had faded from him the way a poppy crumples after only a few hours. I looked long and hard at him as he lay, mouth half open, snoring softly. His suit was rumpled, his fair hair sticky with sweat from the nightmare that tossed his head and made him occasionally moan in torment. He had biscuit crumbs in his cravat, and the sour smell of whisky on his breath.

No pity touched me. This was a man I had loved, and who had poured on me weeks and months of lawful, generous loving. But he had execrated me, and he threatened my safety at Wideacre. The blackness of my sin had half destroyed him; now I wished it had killed him outright. If he continued drinking at this pace it would indeed have proved a fatal wound, and I would be at peace once again. I held my silk skirts out so the whisper of the fabric did not prompt a sweet dream of remembered happiness, and I stepped slowly and carefully to the door. I locked it from the outside, and he was safe in my power.

I was safe too.

Then I climbed the third flight of stairs to the room at the very top of the west wing, and set a taper to the logs in the grate, and to the candles. I opened the other door that connects with the main part of the house where Harry waited, shirtsleeved and barefoot, in patient silence lit only by the light of his bedtime candle.

We held each other like lovers, not like the fierce sensual enemies we so often were in that room. With my husband drunk and dreaming horrors downstairs, and someone, some enemy, perhaps even an enemy I knew well, sleeping and plotting less than fifty miles from me, I did not feel like a storm of passion with Harry. I needed some loving; I needed some kissing; I needed, with all my frozen, frightened heart, some tenderness. So I let Harry take me in his arms and lay me on the couch as if we were tender lovers, and then he kissed me and loved me with tenderness. In many ways this gentle, marital exchange was the most perverse and infamous act of all that we did.

But I did not care. I cared for nothing, now.

Afterwards, we lay sprawled in an easy tangle on the couch, watching the firelight flickering, and drinking warm claret. My chestnut hair was spread in a tangle across his warm soft-haired chest. My face rested against the plump column of his throat. I was tired; I was at peace. I was bruised but not pained. Any woman in the world would have been deeply satisfied and ready for sleep.

‘Harry,’ I said.

‘Yes?’ he said, rousing himself from his half-doze, and gathering me closer into his warm hug.

‘There is something I have been waiting to tell you for some time, Harry,’ I said hesitantly. ‘Something that I am afraid may grieve you, but something you have to know for the good of Wideacre.’