The Fundamentals of Hogan

I might also point to Nick Faldo, with whom I started working in 1985. Faldo wanted to rebuild his swing so that he could rely on it under the pressure of major championships. It took him two years to incorporate the changes, and in 1987 he won the British Open after making eighteen straight pars during the final round—proof that his swing could stand up under extreme pressure. He has since gone on to win two more British Opens and three Masters. I learned while working with Faldo that it really is possible for a golfer to revamp his swing, as Hogan suggests it is. Clearly, not all golfers want to put in the time that Faldo did, because he is, of course, a touring professional, cast in the Hogan mold of dedication. Still, as Hogan points out, any golfer who is committed to change can improve as long as he works on the fundamentals. Faldo, like Hogan and now Tiger Woods, has been driven by the search for perfection. Your own search might be so that you can work toward winning a club event, or simply to reach a new personal best in terms of ball-striking and scoring. Hogan believed it and I believe it: you can improve. Just as I was amazed to see the changes in Faldo over time I have been equally amazed to see the changes in amateurs with whom I have worked, though not at all surprised to observe how much they have enjoyed their golf as a result.

Hogan’s ideas provide an extraordinarily valuable resource for our continued studies. Five Lessons especially is a constant and consistent companion to many golfers, teachers, and players. Nick Price has read and reread and marked up the book with comments and observations; there are places he agrees with Hogan and occasions where his opinions differ. I plan to do something similar here. I will, in a sense, mark up Five Lessons and examine it from our turn-of-the-century perspective. I hope I can accomplish this act of interpretation judiciously and with the respect it requires. I would also encourage you to read or reread Five Lessons—Hogan’s swing theory becomes that much clearer.

The idea, of course, is to help you work toward developing a reliable swing. The more reliable your swing, the more you can trust it, and the greater your confidence. The chances of your building this confidence will be enhanced when you feel secure with what you are doing; this security will come when you incorporate the correct fundamentals so that you can produce a reliably effective swing and control the distance, direction, and trajectory of the ball. The mental side of the game, including course strategy, becomes that much easier. The idea is to know where the ball will and won’t go. The golfer has to realize that every shot won’t be perfect: the key is learning to hit “better bad shots,” keeping the ball in play through sound mechanics—basically, believing in your technique, making it subconscious and instinctive through practice so that you can go out on the course to simply play the game.

When you reach this point you have achieved the ultimate—you can think about quality practice sessions in terms of just maintaining and refining your technique and then hitting different types of shots for pure enjoyment—for example, draws and fades, high and low shots. You will then have plenty of time left to practice that all-important short game. You certainly don’t have to be like Ben Hogan in your practice habits; however, making good use of your time and practicing with a purpose will go a long way toward your shooting lower scores.

I base some of the key building blocks in my teaching upon Hogan’s fundamentals: grip, setup, plane, the lower body motion, the basic use of the big muscles, the understanding of the action of the hands and arms, the use of physics to strike the ball, the application of drills and mirror practice to learn technique. His influence is plain to see in my teaching. I based my first book, The Golf Swing, on the style and layout of Five Lessons. Hogan’s book is, I feel, the first systematic approach to teaching the full swing, a step-by-step guide to help a golfer understand the components of the swing and then to put them all together.

Even though he wrote his book in the 1950s, much of what Hogan said, when examined closely, holds true today, so it is no surprise that Five Lessons is a focal point of every serious golfer’s library. It has played a major role in the evolution of teaching the game. Like Hogan, I believe that many golfers are simply spinning their wheels and not improving. Hogan himself once spun his own wheels. In an article in Esquire in 1942 called “When Golf Is No Fun,” Hogan wrote that he had taken the same sort of punishment that struggling amateurs know all too well.

“Before I really found my game,” Hogan wrote, “I might be hot one round and cold the next for no reason I could figure out. After rounds when I wasn’t scoring well I would practice for hours trying to get to hitting the ball, and finally go home disgusted.”

But Hogan wouldn’t tolerate that feeling, so he studied the golf swing carefully with an eye to eliminating his sources of error and making it efficient and reliable. He was able to do this, and came to believe that with the proper understanding and application of the fundamentals and with patience, everyone has it within his or her grasp to play good golf. Hogan is right when he says, “Doing things the right way takes a lot less effort than the wrong way does.” I agree, and invite you to examine the following pages with a view to learning to build a reliable and efficient swing. I am confident you will be on the way to reaching your potential when you understand Hogan’s principles along with some alternative approaches that we have learned about the golf swing in the last few decades. That is why I have written this book.

THE HANDS

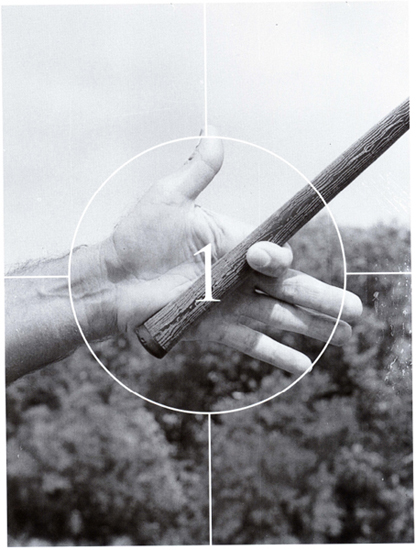

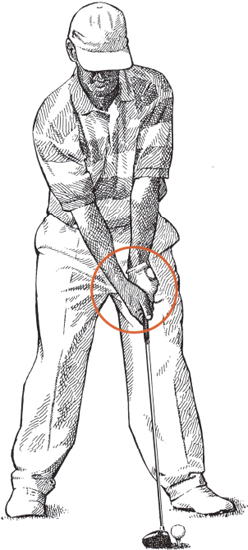

Ben Hogan said, “good golf begins with a good grip.” He believed and taught that a fundamentally correct grip allows the hands to work as a unit on the club—so important for consistent shotmaking. Hogan felt that golfers downplayed the value of a sound grip in terms of its contribution to speed, consistency and control of the clubhead through impact.

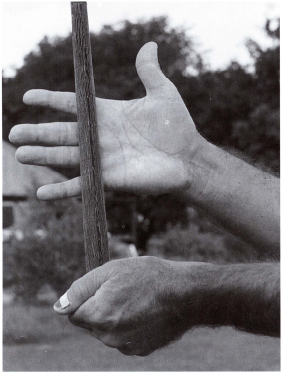

Left Hand Hogan favored a palm grip for the left hand, feeling that this offered the player a better chance for maintaining control of the club than if it were placed in the fingers. He said that the club should lie across the left hand so that it runs diagonally from the heel pad to the first joint of the index finger. Hogan also felt that pressure points in the grip were important for maintaining control. The main pressure I points in the left hand were up from the last three fingers and down from the fleshy palm-pad under the thumb. These pressure points helped prevent the club from coming loose during the swing, and helped keep the club solid at impact. When Hogan looked down at this completed left-hand grip, he saw that the V between his thumb and forefinger pointed toward his right eye.

Hogan placed the club well into the palm of the left hand.

Hogan felt that the club should not be placed down in the fingers of the left hand.

Grip pressure comes up from the last three fingers and down from the palm pad.

The V between thumb and forefinger of his left hand pointed to the right eye.

To maintain grip pressure is to maintain control.

When grip pressure is lost, hands become loose and control is lost.

Hogan placed the club in the fingers of the right hand across the top joints.

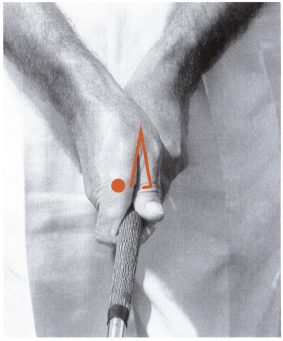

Right Hand As opposed to the left hand, palm-oriented grip, Hogan believed that the club should be placed in the fingers of the right hand; specifically, the club should be placed across the top joints of the fingers—just below the palm. His thoughts about the right hand grip in general were that it should work equally with the left hand, but that it should not play an overpowering role in the swing.

Right hand folds on top of the left thumb.

To ensure that his hands worked as a unit, Hogan placed the little finger of his right hand in the groove between the index and second finger of his left hand. He then positioned the cavity in his formed right hand on top of his left thumb. Pressure in the right hand came from the middle two fingers and from the knuckle above the right index finger. When Hogan looked down at his completed right-hand grip, he saw that the V between his thumb and forefinger pointed to his chin (as opposed to the V in his left-hand grip pointing to his right eye). As a practice aid to neutralize the stronger right hand and also to feel how the hands should work together, Hogan practiced swinging the club (but not hitting a ball) with his right thumb and forefinger off the shaft.

Hogan wanted his grip to be secure, comfortable and alive, and tension free. A good grip allows the player to maintain control of the club and to hit the variety of shots—high and low shots, draws and fades—that are necessary if one is to become a complete player. Hogan advised golfers to work constantly on their grip to ensure it was perfect in every detail.

Left thumb fits in cavity of right hand.

The little finger of the right hand fits in the groove between the first and second fingers of the left hand.

The middle fingers supply the pressure.

Hogan suggests a drill in which you swing the club with the thumb and finger off the shaft.

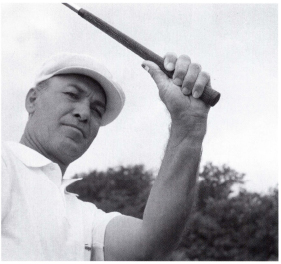

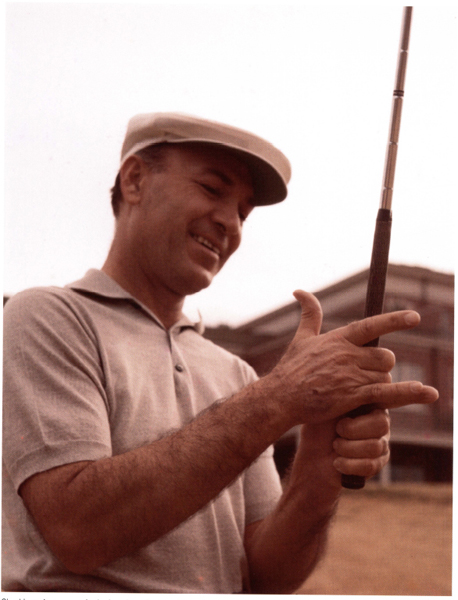

Hogan had unusually flexible wrists and thumbs.

Hogan liked the V between thumb and forefinger of the right hand to point to the chin. The knuckle above the index finger helped provide pressure.

Checking grip pressure in the last three fingers of the left hand and middle two of the right.

My View Hogan’s grip looked immaculate. It was as if his hands were molded to the golf club. He wanted, as he indicated, a secure, alive, and comfortable grip—a grip that would offer the most effective means for him to control the ball. He never wanted his hands to come apart or separate from the club, so he worked long and hard at perfecting his grip, making a few changes to it over the years. The grip changes were an integral part of the much-discussed Hogan “secret.” In his early years he had a severe problem with a wild hook, so naturally he built his swing around incorporating an anti-hook move. He was quoted as saying, “I hate a hook. It nauseates me. I could vomit when I see one.” It’s not surprising, then, that Hogan’s “secret” was based on his finally being able to eliminate the hook from his game. I will discuss his “secret” in due course.

In my opinion most golfers run into big problems when they employ an ultra-palmy left-hand grip in the Hogan mode. You can see in the photograph of him taken down the line that the club sits extremely high in his palm. The problems are magnified when the palmy left-hand grip is combined with placing the club purely in the fingers of the right hand. Such a grip will, for most golfers, accentuate or even produce a slice; they will be unable to generate any real clubhead speed or to square the clubface in the impact area. Hogan, however, was able to master this method of gripping the club; in my opinion, not many players are able to handle it.

Club sits high in palm of Hogan’s left hand.

You see, Hogan was an exceptional athlete who had superb dynamics in his swing, meaning that he transferred collected energy to his clubhead in an astonishing, powerful fashion. He had strong, fast hands and his action was very much like cracking a bullwhip. His swing tempo was upbeat and he had tremendous overall flexibility, especially in the wrist/thumb area; the result was that he could swing the club back beyond parallel—far beyond parallel—at the top. Look at the curvature in his thumbs (see page 16); the way they bowed backward was extraordinary, and along with the flexibility in his wrists was a major part of the reason that he had so much wrist cock and clubhead lag in his swing. I first became aware of the flexibility in his thumb and wrist area after looking at still pictures of Hogan on his downswing when I was a kid, and I then tried to recreate the angles and the lag that he had coming down into the ball. That was considered a power position and I wanted to get into it. But I, along with just about every golfer I have encountered, had no chance of doing that. We don’t have that flexibility in our wrist/thumb area.

So much flexibility and lag can also cause problems. A clubface even slightly closed when combined with tremendous lag and hand speed can lead to problems at impact, as it did at times for Hogan. With the longer clubs, especially the driver and fairway woods, and under the pressure of tournament play early in his career, a severe hook would show up. Hogan had to find a way to stop this shot and to pacify his hands so that he could gain more control. Distance was never a problem, but control and timing were. Hogan thought that by changing his grip he would solve his directional problems—his strategy certainly went some way toward doing so.

Hogan made a couple of changes to his grip to cure his hook, and although he regarded these changes as minor, I feel they were major. He made the first change in 1945, when he shifted his left thumb up the shaft into what is considered a “short thumb” position. The “long thumb” (that is, where the thumb is stretched down the shaft as much as possible) encourages wrist cock, and so when Hogan shortened it he was able to firm up and restrict his wrist cock. This, in turn, had the effect of making his swing considerably shorter and keeping his club more under control at the top. By firming up his wrist cock he was also able to reduce the excessive amount of lag coming down. This greater control helped him improve his timing.

Having shortened the thumb up, Hogan’s next step in his grip change was to move his left hand around in a counterclockwise direction (more to the left on the shaft), showing just one knuckle when he looked down on it; this placed his “short” left thumb over to the center as opposed to the right of the shaft. In conjunction with moving his left hand to the left he placed his right-hand grip more in his fingers and on top of the shaft, so that, I assume, each hand would match the other.

Long thumb

Short thumb–short swing.

Short thumb

Long thumb–long swing.

David Duval’s strong left–hand grip.

Consequently, his grip was now “weakened,” to use a popular golfing term (though this does not mean it was weakened in strength). He felt the changes helped get the clubface more open; he could now hit hard with his right hand, without as much fear of the face closing and producing a hook. At the point of impact he could keep his left hand or lead hand firm and under control, and in turn have more control over the face. He had nearly achieved his goal of eliminating his hook. One more little key would solve the puzzle and eliminate the disastrous hooks that plagued him. That was his secret, which, as I have said, I will examine later.

Hogan felt that the changes he made were simply modifications to a sound grip and were particularly beneficial for him. It was no surprise, however, that many players copied Hogan’s grip exactly, whether or not they had problems with hooking the ball. Many were unsuccessful in adopting his grip. Most golfers today, even tour players, can profitably adopt a slightly stronger grip with the hands (especially the left hand—showing two to three knuckles when you look down at it) turned in a more clockwise fashion to the right on the club; and they can do this without having to fear severe hooks. This is a more natural and advisable route to follow; it is more natural because your hands are in this position when they hang down by your side. Two players who employ ultra-strong grips—Paul Azinger and David Duval—are most assuredly controlled faders of the ball. There is more to curing a hook or promoting a fade than just weakening the grip.

Those of you who are thinking of shortening your left thumb to gain more control should bear in mind an important factor: namely, that Hogan’s flexibility in his wrists and the curvature in his left thumb made it possible for him to shorten it on the club while still keeping the entire thumb flat on the grip. Most players by shortening the thumb would create a noticeable gap under the thumb, as it bunches up. This would lead to reduced rather than increased control of the clubhead because less of the thumb would be on the club. Generally, I prefer golfers to have a “longish” left thumb to aid cocking and leverage.

Hogan’s grip looked great, no question. And it worked beautifully for him. The grip helped cure Hogan’s hook. But most players don’t hook the ball and in fact tend to slice the ball. Not only would the Hogan-like grip not cure their slice, it would make them hit some awfully big banana balls. A weak grip wouldn’t be a cure. It would be a curse.

To Become an 80-Breaker - or Better I have tried to explain why Hogan gripped the club as he did. He obviously gave a lot of thought to the question of how to best come up with an anti-hook grip; so critical an element was this grip in his discussion of the fundamentals of golf that he devoted an entire chapter to it in Five Lessons. Gardner Dickinson, in fact, wrote that he thought the book “was, more than anything, a system of defense against a low, ducking hook, a problem that afflicts very few golfers.” Hogan achieved the grip he wanted through trial and error, and his final version went a long way toward helping him develop tremendous control over his swing and the golf ball. At the same time there are alternatives to the manner in which he gripped the club. It is important to realize that Hogan’s grip was a personal creation that helped him neutralize his tendencies. Art Wall, Jr., the 1959 Masters winner who played frequently with Hogan, confirmed to me that Hogan, being such a fast swinger, used extremely heavy and stiff-shafted clubs—yet another obvious component of his anti-hook plan. (Hogan also used clubs with flat lies, another anti-hook measure.) His ability to control these clubs demonstrated how strong he was physically, and also how much clubhead speed he was able to create. Many players who tried to hit his clubs found that doing so was an exercise in futility. They simply could not handle such heavy, stiff clubs.

Hogan advocated a grip that positions the club in the palm of the left hand and purely in the fingers of the right hand. I share these ideas to a point, but I would advise some subtle changes especially for people who (1) do not have real suppleness in the wrists and thumbs, and (2) would like to hit a consistent draw—probably a large percentage of the world’s golfers!

If the club sits too high in the palm, it’s easy to wear a hole in the glove.

Let’s first consider the left hand. In my experience, one of the most serious problems that golfers have is that they hold the club so much in the palm of the left hand that they tighten and freeze the wrist action. This makes it difficult for a golfer to cock the wrists correctly and to create any significant leverage. The club sits too high in the hand, to the extent that many golfers wear a hole in their gloves at the top of the palm. This is all brought about because the golfer feels a lack of power and tries to force some motion into the swing. The forced movement occurs mainly at the start of the swing, at the top of the backswing, and in the impact area. All this effort causes movement and friction between the hand and the grip of the club—the hole in the glove results. But a solution is available, a simple modification that for most people feels very good very quickly. It is quite amazing to see how easily the club works and the leverage that one creates when positioning the left hand properly; after all, the left hand acts as a hinge between the arm and the club, and promotes a fluid motion. The golfer feels that the club is in balance and that little, if any, effort is required to produce power and “snap” in the swing. (I’ll explain the solution in a moment.)

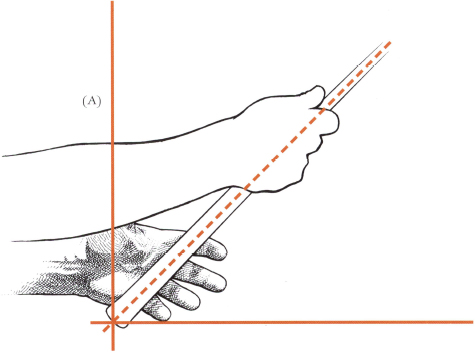

Positioning the club correctly in the left hand.

Hogan, because of his flexibility, had considerable natural leverage. His wrist action—the way he set the club going back and created so much snap with it through impact—helped him generate tremendous power. In an effort to create leverage and power, golfers need to correctly cock and uncock the wrists. If the golfer grips the club too much in the palm of his left hand then it is all too easy to lose leverage. A variety of common faults also arise, such as picking the club up from the start, rolling or fanning the clubface, the left arm breaking down, and the right elbow moving into a faulty position. The golfer compensates for, and reacts to, a bad grip by trying to force the club through, usually with the upper body, to try to generate some power. The wrist action of hitting a golf ball is rather like cracking a whip; try to crack it with stiff, wooden wrists and see how the rest of the body incorrectly gets into the act to try to help. The problem of gripping the club too much in the palm of the left hand is so widespread that placing it correctly has frequently changed golfers overnight from being sheers into players who draw the ball, while turning short hitters into solid ball-strikers who now get some distance. That distance comes because the golfer is now able to cock his wrists correctly, create more snap and leverage, and really accelerate the club through the ball.