The Fundamentals of Hogan

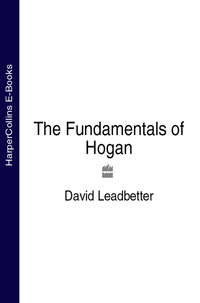

Closing the left hand around the club.

Neutral left hand grip: curve at base of wrist; two knuckles showing; V between thumb and finger points up toward your right ear.

Left Hand Here’s the way I’d like you to place your left hand on the club. Hold the club up in front of you in your right hand, angled at forty-five degrees to your body. Now bring your left hand from the target at ninety degrees to the shaft and place it on the club so that it fits diagonally across the palm (A) just under the base of the little finger running up through the crook of the forefinger (the midsection hinge where the forefinger bends). Now simply close your hand around the club (B). Let the thumb sit naturally as flush as possible straight down the shaft, neither overextending it nor shortening it, and place it close to the index finger. You should be able to see about two knuckles on your left hand (C) as you hold the club up in front of you; this is a “neutral” grip. (I’m sure Hogan, given his weak grip, would have seen only one knuckle if he held his hand up.) If you are a severe sheer try to see three knuckles—a “strong” grip. At the base of the wrist (the top of the glove) you should see a slight cup or curve. The V between the thumb and forefinger should point toward your right ear. This image will help you achieve a stronger grip. The left-hand grip is basically a palm grip, but the club is low down in the palm toward the fingers, which encourages movement and cocking in the wrist.

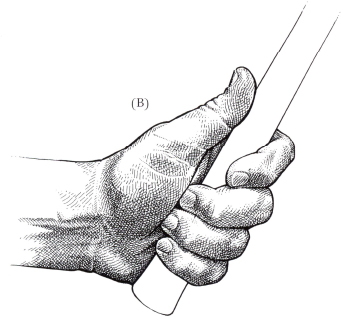

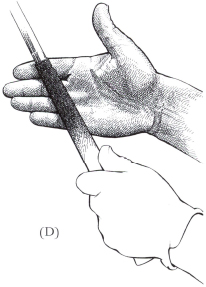

The right-hand grip is primarily a finger grip.

The right index finger and thumb form a “trigger” position

It is essential that you get this left-hand placement correct. Be precise with how you place your left hand on the club. Placing the club in your left hand in this manner should make you far more aware of the weight of the club without any tension in the hand. The wrist will now be in a favorable position to cock naturally and supply that all-important leverage. The final point regarding the left-hand grip is more of a preference than a fundamental, in that Hogan preferred to hold the club at the very end of the grip. I advise most players to hold the club so that about one-half to one inch is showing at the end beyond the little finger. Hogan felt that holding the club at the end allowed him to reduce some tension, and swing a touch slower. As I say, this is a matter of preference. Experiment to find what works best for you.

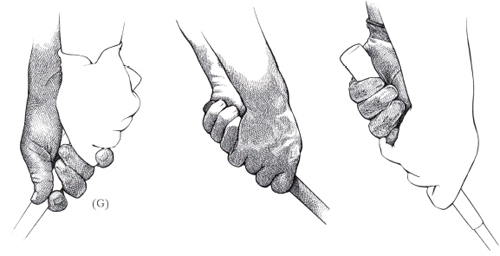

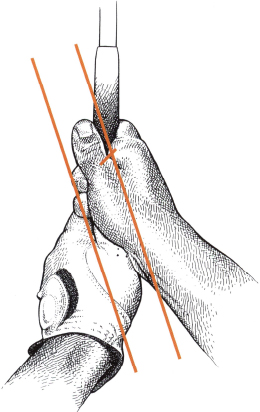

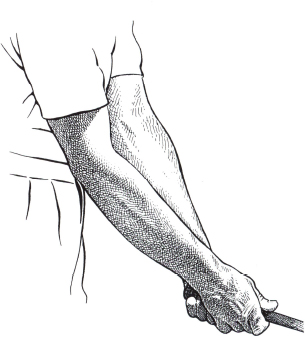

Right Hand Now let’s examine the right hand. Hogan liked the club to fit directly in the fingers, along the top joint line underneath the pad of the palm. My contention is that if you held the club up with your right hand only, you would see that it would fit diagonally across your hand and in fact come into contact with the palm just below the little finger. I agree with Hogan’s belief that the right-hand grip is basically a finger grip. But I feel that gripping the club diagonally across the right hand matches the diagonal look of the left hand. Most players, I believe, look more secure with this grip. Once again, hold the club up in front of you, this time with your left hand, at an angle of forty-five degrees. Place the club diagonally across the fingers of the right hand (D). Slide your hand down the club and link the baby finger between the first two knuckles of the left hand (E), a la Hogan. Now fold the right hand over the left thumb, so that the left thumb slots into the hollow underneath the thumb pad that the right hand provides in this position (F). It’s important to neutralize the potentially destructive pincer action of the right index finger and thumb. Position the right index finger and thumb on the club in a trigger-like fashion while allowing a slight gap to form between the first two fingers (G). Without a trigger position, the tendency is for the right hand to grab the club like a hammer, which, apart from the extra tension, places the right arm and shoulder in too dominant a position at address.

Hogan’s preference was to hold the club at the top of the grip-I prefer players to have one-half to an inch showing.

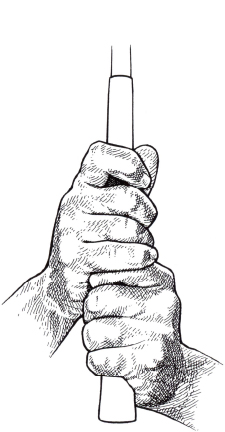

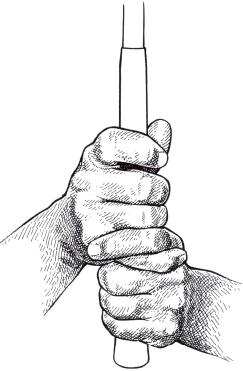

The key to getting a good grip every time (certainly while learning it) is to position the hands on the club while pointing it up in the air at forty-five degrees and looking at it at eye level. Most golfers have a poor grip because they attach their hands to the club while it is angled down to the ball, often grabbing it initially too high in the palm of the left hand and sloppily with the right hand. Trying to adjust your grip from this position is a losing battle. Why not get the grip right from the start? Be disciplined with the grip routine I’ve suggested and your grip will soon feel comfortable and natural.

The end result of a disciplined approach-a correct and comfortable grip.

Because modern-day shafts taper to a large degree and many grips are very skinny at the lower end, I advise my students to add a couple of extra layers of tape under where the right hand fits. This thicker grip encourages a more diagonal look and facilitates a trigger feeling rather than the hammer feeling. The V formed between the thumb and the forefinger on the right hand should point somewhere toward the right shoulder rather than toward the chin as Hogan suggested. However, if you are a good player who has problems hooking, I certainly would explore the idea of getting your right-hand grip a little more in the fingers and on top of the shaft, as Hogan did in order to promote a situation where you get the face more open at impact. It’s one of those trial-and-error situations, and the weaker right hand might help. The general idea, then, is to encourage a grip where the hands are parallel to and match one another so that they sit uniformly on the club.

When looking down at your grip, your hands should generally be parallel to one another–with the V of the right hand pointed approximately toward the right shoulder.

Hogan’s modification to the Vardon grip.

It is vital, as Hogan believed, that the hands work as a unit and not come apart. I’ve always liked Hogan’s slight modification to the Vardon grip—the idea of the baby finger of the right hand fitting between the index and second fingers rather than just riding piggyback as Vardon’s did. Hogan’s grip in my opinion joins the hands more solidly together and is the linking process I recommend. Although some great players with smaller hands do use an interlocking grip—Jack Nicklaus, Tom Kite, and Tiger Woods, to cite three—the overlapping or Vardon-type grip in my opinion puts less stress on the joints of the fingers and works better for players with medium-to-large size hands.

A few closing thoughts on the hands: in assuming your grip, do maintain pressure in the last three fingers of the left hand. Also place and maintain some pressure from the lifeline of the right hand onto the left thumb. This pressure will help keep the hands together and working in synch during the motion of the swing. The golfer who adopts the correct grip, where he feels the balance and weight of the swinging club without undue tension and is able to cock the wrists fully and freely, will usually feel comfortable with it immediately. Many people are wary of changing their grips because they are concerned that it will take them months to feel better with it. But I have found that the player willing to make the change will soon feel as if he has always held the club this way—in my view, the natural way. This grip works very well for all levels and ages of players—men and women, juniors and seniors, even tour players.

The original Vardon grip.

Interlocking grip.

The grip I encourage my students to develop is still primarily a palm grip in the left hand and a finger grip in the right hand, but with some minor alterations that could make a world of difference to your game.

Finally, remember that a grip is not always as it appears. From the outside it may look quite good, but you can only assess a grip once you open it up and see how the club lies in the hands. Check your grip regularly because it’s easy to revert to old habits. If you are going to transfer power through your hands into the clubhead, then you need to position your hands on the club perfectly every time. A good grip sends a strong message that you mean to play your best golf.

ADDRESSING THE BALL

Ben Hogan felt that the address position was the next significant step after the grip. The “setup,” as it is commonly called, consists of a golfer aligning himself properly to the target and then positioning his body in such a way that he can move freely during the swing while in balance. Setting up correctly, Hogan believed, would help accomplish the goal of creating power with the big muscles and then transferring it to the clubhead.

When Hogan moved into his setup, he aimed the clubface toward the target and then aligned his body to the clubface. His stance was fairly wide, giving a firm foundation for good balance. In Hogan’s view, a golfer hitting a five-iron should place his feet about shoulder-width apart. The stance should be wider for longer clubs, and narrower for shorter ones. A stance that is too wide or too narrow will compromise balance and freedom of motion.

Right foot at ninety degrees, left foot turned out a quarter of a turn.

Hogan proposed that the golfer place his right foot at ninety degrees to the target line and then place his left foot into position about a quarter of a turn toward the target—approximately twenty degrees. A golfer who sets his left foot in this manner would not over-rotate his hips as he swung the club back. However, Hogan felt that splaying out the right foot in the same manner and not ninety degrees to the target would promote swaying, dipping or collapsing the left arm because of the excessive freedom which the turned-out right foot provides. These faults lead to a weak, uncoiled position at the top of the backswing. Pointing the right foot out can also force the arms and club to move out and around the right hip as they make their way down to the ball.

Hogan believed a splayed-out right foot can lead to swing problems.

No less esteemed an observer of the swing than two-time U.S. Open champion and Masters winner, Cary Middlecoff, believed that Hogan’s advice to turn the left foot outward had long been standard procedure. “That goes at least back to (Harry) Vardon,” Middlecoff wrote, “and it has always been generally agreed that this positioning of the left foot facilitates the downswing movement of the hips and makes it easier for the player to move freely through the ball.”

In thinking about the arms at address, Hogan agreed with the long-held principle that the player should strive to achieve a maximum arc. Horace Hutchinson, the 1886 and 1887 British Amateur champion, and a respected author, wrote in 1895 that, “In leaving the ball, the clubhead should swing back as far as possible,” and that the arms should be allowed “to go to their full length as the clubhead swings away from the ball, or as nearly to their full length as is possible without further stretching.” Nearly half a century later, Bobby Jones wrote that the arc of the swing should be “made very broad so that space and time for adding speed to the clubhead coming down will be as great as possible.” Hogan was certainly following accepted theory in advocating a maximum arc. Hogan worked on the premise that at least one arm needs to be straight or fully extended throughout the swing—a key to achieving a maximum arc, power and consistency.

Inner elbows pointing to the sky: Hogan’s image of a rope binding the arms.

At address, Hogan wrote that the upper parts of the arms pressed against the chest and the elbows were close together and pointing toward their corresponding hipbone. He pointed out that the pocket of each elbow—the small depression on the inside of the joint—should face the sky and not its opposite. His image at address was of a rope binding the elbows and arms together. He wanted the golfer to maintain that elbows/arms relationship throughout the swing. And while he spoke about the left arm hanging straight at address, he advised that the right arm should have a slight bend at the elbow. This allows the right elbow to fold close to the body as the club is swung back and to point to the ground (the ideal position in his opinion) at the top of the backswing.

Elbows should not face each other.

Hogan’s final point regarding the address position concerned posture—the way a golfer positions his trunk and knees. His mental image was of a golfer starting with an erect position at address, and then sitting down a couple of inches as if sitting on a seat stick (see page 33). This semi-sitting position would give the player a sense of heaviness in the buttocks and promote liveliness in the lower legs, and, in Hogan’s view, put the weight back towards the heels. There must be no slouching of the shoulders, stiffness in the legs, or collapsing of the knees, as seen in many golfers. Tommy Armour, the superb teacher and player who won the 1927 U.S. Open, the 1930 PGA Championship and the 1931 British Open, recommended a similar position. As he wrote, “You will stand as upright as you can to the ball; not stiff, but comfortably upright with the knees flexed a little bit.” Hogan also advocated a flexed knee position and in addition liked the knees to be pinched slightly inward (the right knee a fraction more than the left). By placing himself in this very athletic position, Hogan felt he was completely stabilized and balanced at address, ready to make the proper swing.

Left arm hanging straight.

Left arm hangs straight, right arm kinked in.

Hogan exaggerating excessive knee flex.

Hogan mimicking poor posture.

My View

Still pictures cannot possibly capture the athleticism of Hogan’s setup. His setup was powerful, alive, ready for action, and very purposeful. His tall posture with very little forward upper-body bend or knee flex was determined by his build—just under 5 feet 9 inches tall with long arms and strong gluteus maximus muscles; his rear end, to put it delicately, was sizable and strong. This encouraged him to stand erect and—in his case—facilitated his shoulders turning on a flat horizontal plane, which produced the flattish, characteristically Hoganesque swing plane. Hogan said he liked to feel his weight back on his heels. But I sense that his balance was more forward, toward the arches and the balls of his feet, as is the case with most athletes—for example, in basketball, where the shooter sets himself for a free throw. Photographs of Hogan suggest that even though he stood tall, his weight was not back on his heels as much as he thought.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги