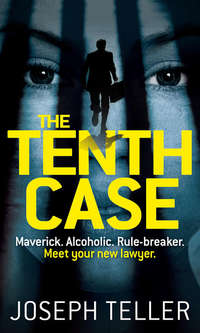

The Tenth Case

“Oh?”

“I’ve gotten an order freezing all of Barry Tannenbaum’s assets,” said Burke. “Including a bank account in Samara’s name.”

“Shit,” was all Jaywalker could think to say.

Tom Burke had only been doing his job, of course. He’d been able to trace the deposits to Samara’s account and demonstrate to a judge that every dollar—and there were currently nearly two hundred thousand of them—had come from her husband. Under the law, if Samara were to be convicted of killing him, she would lose her right to the money, as well as to any other of Barry’s assets. Next, Burke had informed the judge that he’d already presented his case to a grand jury, which had voted a “true bill.” That meant an indictment, which amounted to an official finding of probable cause that Samara had in fact committed a crime resulting in Barry’s death. Based upon that, the judge, a pretty reasonable woman named Carolyn Berman, had had little choice but to freeze all of Barry Tannenbaum’s assets, the bank account included.

Even if Burke and Berman had only been doing their jobs, the result certainly added up to a major headache for Jaywalker. The good news was that he could now skip going to the bank. But that consolation was more than offset by the fact that instead he had to spend two days drawing up papers so that he and Burke could go before the judge and argue about the fairness of the ruling.

They did that on a Friday afternoon, convening at Part 30, on the 11th floor of 100 Centre Street, the Criminal Court Building. Jaywalker’s home court, as he liked to think of it.

“The defendant has a constitutional right to the counsel of her choice,” he argued.

“True enough,” Burke conceded, “but it’s a limited right. When you’re indigent and can’t afford a lawyer, the court assigns you one. Only you don’t get to choose who it is.”

“But she’s not indigent, and she can afford a lawyer,” Jaywalker pointed out. “At least she could have, until you two decided that instead of her paying for counsel, the taxpayers should get stuck footing the bill.”

It was a fairly sleazy argument, he knew, but there were a half-dozen reporters taking notes in the front row of the courtroom, and Jaywalker knew that the judge didn’t want to wake up tomorrow morning to headlines like JUDGE RULES TAXPAYERS SHOULD PAY FOR BILLION-AIRESS’S DEFENSE.

In the end, Judge Berman hammered out a compromise of sorts, as judges generally try to do. She authorized a limited invasion of the bank account for legal fees and necessary related expenses. But she set Jaywalker’s fee at the same seventy-five dollars an hour that it would have been had Samara been indigent and eligible for assigned counsel.

Great, thought Jaywalker. Here I got paid thirty-five grand to cop her out on a DWI, and now I’m going to be earning ditch-digger wages for trying a murder case.

“Thank you,” was what he actually said to Judge Berman.

With that he walked over to the clerk of the court and filled out a notice of appearance, formally declaring that he was the new attorney for Samara Moss Tannenbaum. And was handed a 45-pound cardboard box by Tom Burke, containing copies of the evidence against his client. So far.

Nothing like a little weekend reading.

6

A LITTLE WEEKEND READING

It turned out to be a horror story.

Jaywalker began his reading that night, lying in bed. The cardboard box Burke had given him contained police reports, diagrams and photographs of the crime scene, the search warrant for Samara’s town house, a “return,” or list of items seized there, a typewritten summary of what Samara had said to the detective who first questioned her, requests for scientific tests to be conducted on various bits of physical evidence, and a bunch of other paperwork.

It was a lot more than the prosecution was required to turn over at this early stage of the proceedings. A lot of assistants would have stonewalled, waiting for the defense to make a written demand to produce, followed up with formal motion papers and a judge’s order. Tom Burke didn’t play games like that, a fact that Jaywalker was grateful for.

At least until he began reading.

From the police reports, Jaywalker learned that when Barry Tannenbaum hadn’t shown up at his office one morning and his secretary had been unable to reach him either at his mansion in Scarsdale or his penthouse apartment on Central Park South, she’d called 9-1-1. The Scarsdale police had kicked in the door, searched the mansion, and found nobody there and nothing out of order. The NYPD had been luckier, if you chose to look at it that way. Let into the apartment by the building superintendent, they’d found Barry lying facedown on his kitchen floor, in what the crime scene technician described as “a pool of dried blood.” If the terminology was slightly oxymoronic, the meaning was clear enough.

There’d been no weapon present, and none found in the garbage, which hadn’t been picked up yet, on the rooftop, or in the vicinity of the building. Officers went so far as to check nearby trash cans and storm drains, with, in police-speak, “negative results.”

There was no sign of forced entry, and no indication from the security company that protected the apartment that any alarms had gone off. The apartment was dusted for fingerprints, and a number of latent prints were lifted or photographed. Blood, hair and fiber samples were collected.

The medical examiner’s office was summoned, and the Chief Medical Officer himself, not all that averse to publicity, responded. On gross examination of the body, he found a single deep puncture wound to the chest, just left of the midline and in the area of the heart. There appeared to be no other wounds, and no signs of a struggle. The M.E. took a rectal temperature of the body. Based on the amount of heat it had lost, as well as the progression of lividity and rigor mortis, he was able to make a preliminary estimate that death had occurred the previous evening, sometime between six o’clock and midnight.

The building was canvassed to determine if anyone had heard or seen anything unusual the night before. Only one person reported that she had, a woman in her late seventies or early eighties, living alone in the adjoining penthouse apartment. She’d heard a loud argument between a man and a woman, shortly after watching Wheel of Fortune. She recognized both voices. The man’s was Barry Tannenbaum, whom she knew well. The woman’s, she was just as certain, was his wife, known to her as Sam.

According to TV Guide, Wheel of Fortune had aired that evening at seven-thirty Eastern Standard Time, and had ended at eight.

The doorman who’d been on duty the previous evening was located and called in. He distinctly recalled that Barry Tannenbaum had had a guest over for dinner. As he did with every non-tenant, the doorman had entered the guest’s name in the logbook upon arrival and again upon departure. Although in this particular case he hadn’t required her to sign herself in. The reason, he explained, was that he knew her personally.

Her name was Samara Tannenbaum.

At that point a pair of detectives had been dispatched to Samara’s town house. They had to buzz her from the downstairs intercom and phone her unlisted number repeatedly for a full fifteen minutes before she finally cracked the door open, leaving the security chain in place. They told her they wanted to come in and ask her a few questions.

“About what?” she asked.

“Your husband,” they said.

“Why don’t you ask him yourselves?”

The two detectives exchanged glances. Then one of them said, “Please, it’ll only take a few minutes.”

At that point Samara unchained the door and “did knowingly and voluntarily grant them consent to affect entry of the premises.” Jaywalker would go to his grave in awe over how cops abused the English language. It was as though, in order to receive their guns and shields, they were first required to surrender their ability to spell correctly, to follow the most basic rules of grammar, and to write anything even remotely resembling a simple sentence.

Samara had seemed nervous, they would later write in their report. Her hair “appeared unkept,” her clothes were “dishelved,” and she “did proceed to light, puff and distinguish” a number of cigarettes.

They asked her when she’d last seen her husband.

“About a week ago,” she replied.

“Are you certain?”

“Am I certain I saw him a week ago?”

“No, ma’am. Are you certain you haven’t seen him since?”

“Why?” she asked. Jaywalker could picture her nervously lighting, puffing and “distinguishing” a cigarette at that point. “What’s this all about?”

“It’s just routine,” they assured her. “We only got a few more questions.”

“Well, if you don’t want to tell me what this is about,” Samara told them, “you can just routine yourselves right out the door.”

Again the detectives exchanged glances. “We have people who place you at your husband’s apartment last night,” said one of them.

“So what?”

“So we’d like to know if it’s true, that’s all.”

“So what if it is?”

“Is it?”

Samara seemed to think for a moment before answering. Then she said, “Yeah, sure. We had dinner together.”

“At a restaurant, or at your husband’s apartment?”

“His apartment.”

“Did he cook?”

“Barry? Cook?” She laughed. “The man couldn’t boil water. He told me the first thing he did when he bought the apartment was to have the stove ripped out to make room for a bigger table.”

“What did you eat?”

“Chinks.”

Being detectives, they didn’t have to ask her what she meant. Besides, the crime scene guys had found half-empty containers of Chinese takeout on the counter and in the garbage, when they’d been looking for a weapon.

“Are we done here?” she asked. “Or maybe you’d like to know how many steamed dumplings I ate.”

“Did you have a fight?” they asked.

“No.”

“We’ve got people who tell us they heard a fight.”

“So? Big deal. We always fight.”

“Who hit who first?”

“Nobody hit nobody.”

Jaywalker wondered if maybe Samara might not have made a pretty good cop.

“So what kind of a fight was it?”

“A word fight. An argument, I believe they call it.”

“About what?”

“Who the fuck remembers? Stupid stuff. He started it.”

“Then what happened?”

“I don’t know. I told him he could go fuck himself, and I left. Now maybe you’d like to tell me what this is all about?”

“Sure. It’s about your husband’s murder.”

“Barry? Murdered? You’re shitting me.”

They said they weren’t shitting her.

“Wait a minute,” she said, the light finally going on. “You think I killed Barry?”

They said nothing.

“I want a lawyer,” said Samara.

The magic word having been uttered, the interview was effectively over. Nonetheless, the detectives weren’t quite done. “Would it be okay if we had a quick look around?” they asked her.

“You got a warrant?”

“We can get one,” they said. “Or you can save us all a lot of time and trouble.”

She looked them in the eye and said, “I ain’t saving you shit.”

With that, they “did handcuff her, pat her down, administrated her Miranda rights, exited the premises, and transported her to the precinct for fingerprinting, processing and mug shooting.”

God bless.

Whatever time and trouble it had cost them, that afternoon the detectives did indeed apply for and obtain a search warrant for Samara’s town house, aimed at finding “a weapon or other instrument, as well as other physical evidence relating directly or indirectly to the murder of Barrington Tannenbaum.”

Apparently Tom Burke had taken over the writing.

The warrant was executed the same evening. The return listed more than two dozen items that had been seized. It was hard at that point for Jaywalker to appreciate the significance of most of them, but at least three were pretty easy to understand.

6. One silver-handled, steel-bladed steak knife, 9 inches long overall, with a sharply pointed tip and a blade 5 inches long by three-quarters of an inch wide by one-sixteenth of an inch thick, on which there appears to be a dried, dark-red stain.

9. One blue towel, with an irregular dark-red stain measuring approximately 1" x 3".

17. One ladies’ blouse, size S, with a dark-red splatter pattern on the front, approximately 3" in diameter.

If the nature of the items was troubling to Jaywalker, the location where they’d been discovered was just as damning. All three had been found rolled up together and wedged behind the toilet tank of a top-floor guest bathroom.

Those items, along with a number of others removed from the crime scene, were currently being tested for the presence of DNA. Fingerprint comparisons were awaited. In addition, a full autopsy had been conducted on Barry’s body, and a report was expected in a few weeks, as well as serology and toxicology findings. Hair and fiber analyses were being done, too.

Yet as bad as things looked for Samara at the moment, Jaywalker had every confidence that given a little time, they would look a lot worse.

He turned off the light and lay on his back in the darkness. Samara Tannenbaum’s face appeared at the foot of his bed, her eyes darker even than the room, her lower lip pouting.

“I didn’t do it,” she said.

Right.

7

180.80 DAY

Monday was Samara’s “One-eighty-eighty” day, a reference to the section of the Criminal Procedure Law that entitles a defendant to be released unless the prosecution has obtained an indictment or is ready to go forward with a preliminary hearing. A lot of defendants do get released: complaining witnesses disappear, cops screw up and assistant D.A.s occasionally get overextended, and have to pick and choose which cases to treat as priorities and which to let slide. Some defendants are lucky enough to slip into the cracks that are inevitable in a system that processes many thousands of cases a year.

Barry Tannenbaum having disappeared in the most literal sense imaginable, the complaining witness in Samara’s case was now The People of the State of New York, and they weren’t going anywhere. As far as Jaywalker knew, no cops had screwed up, so long as spelling and grammar didn’t count. Tom Burke was certainly treating the case as his top priority, if not his career-maker. Given all that, the chances of Samara’s case slipping into some crack, necessitating her release from jail, were absolutely zero.

Jaywalker explained all this to her before they went before the judge, during a five-minute conversation in the “feeder pen” adjoining the courtroom. The term, no doubt, had come from the fact that the small lockup “feeds” defendants into the courtroom, one by one. But every time he heard it, Jaywalker couldn’t help but picture bait fish being served up to frenzied sharks, or small rodents to ravenous wolves.

“After the court appearance,” he told Samara, “we’ll sit down in the counsel visit room and talk as much as we need. Okay?”

She nodded, looking appropriately worried.

He described what would happen when they appeared before the judge: in a word, nothing. Once an indictment was announced, the only remaining bit of business would be the setting of an adjourned date.

“Can you make a bail application?” Samara asked.

Apparently she’d been getting some jailhouse advice, a commodity never in short supply on Rikers Island. Inmates devour every word of it, never pausing to notice that the dispensers of the advice have one thing in common: every last one of them is still sitting in jail.

“I can,” he told her, “but it’ll only be denied. You’re going to have to wait until we get to Supreme Court.”

“They say that can take years.”

“Different Supreme Court,” said Jaywalker, not helped all that much by a system in which some Einsteins had gotten together and decided to call the lowest felony court in the city supreme. But Jaywalker spared Samara the explanation. What he did tell her was that asking for bail was not only pointless, but might actually hurt their chances later on. Bail was almost never granted in murder cases, and on the rare occasion when it was, it was usually set prohibitively high. In this case, that wouldn’t take much. With her bank account frozen and no other assets to her name, even were a modest bail to be set, Samara had nothing to post it with. So while there might come a time when it made sense to ask for bail, it certainly wasn’t now.

Finally, Jaywalker warned Samara that the press would be in the courtroom. The American public, denied a throne by the founding fathers, makes do with celebrity and wealth in lieu of royalty. How else to explain such curious heroes as Bill Gates, Jack Welch or Paris Hilton? Barry Tannenbaum had been rich. If not quite Bill Gates rich, certainly Donald Trump rich. He’d married a reformed hooker (some commentators, inclined to reserve judgment, preferred the term “former hooker”), forty-two years his junior. Now she’d stabbed him to death.

The press would definitely be in the courtroom.

“Your appearance, please, counselor,” said the bridge-man, once the case had been called.

As always, Jaywalker was tempted to say, “Five-eleven, a hundred and seventy pounds, graying hair…” Instead, he controlled himself, stating his name and office address for the court reporter to take down.

True to form, Tom Burke announced that he’d obtained an indictment against Samara. The judge set a date for arraignment in Supreme Court.

And that was it.

Anyone expecting to find the twelfth-floor counsel visit area to be the functional equivalent of a private hospital room would have been seriously disappointed. But Jaywalker had been there a thousand times before and knew better. The area was laid out more like a ward or, if you wanted to be extremely charitable about it, a semiprivate room.

After being ushered through the middle one of three steel-barred outer doors, he entered the lawyers’ area, a row of bolted-down chairs that extended to the far wall on either side. Each chair had a small writing surface in front of it, with wooden partitions rising on either side. Above the writing surfaces was a metal-screened window. If one squinted sufficiently, he could see that on the other side of the screen was another writing surface, and behind it another bolted-down chair, facing his own.

The inmates were led in through the other doors, one side for men and one for women. That way, segregation was maintained for the three groups—lawyers, male prisoners and female prisoners. Someone had apparently decided that it was safe to permit lawyers of both sexes to mingle.

The arrangement was an imperfect one, because unless you talked in a whisper with your client or resorted to sign language, you ran the risk of being overheard by lawyers on either side of you, and inmates on either side of your client. Still, it was better than talking over some staticky telephone hookup, or through a hole in reinforced glass, so Jaywalker wasn’t about to complain.

You picked your battles.

He spent the better part of twenty minutes reviewing his file on Samara’s case, already two inches thick. He knew it would take a while for them to bring her up from the fourth-floor feeder pen.

When she came in and took her seat across from him, he was struck again by how tiny she seemed, and how vulnerable. He’d stood alongside her in the courtroom half an hour ago, but his attention had been focused elsewhere then—on the judge, the prosecutor, the court reporter, even the media. Now he had only Samara to look at, and what he saw was a young woman on the verge of tears. He wondered if he’d missed that downstairs, when he’d been all business.

“Are you okay?” he asked her.

“No, I’m not okay,” she said, using the heels of her hands to blot her eyes. So much for the verge of tears.

“I’m sorry,” he said. He meant it, both about her obvious distress and the fact that his dumb question had triggered her meltdown.

She took a deep breath, fighting to compose herself. “Listen,” she said, “you’ve got to get me out of here.”

“I’ll do my best,” Jaywalker promised. It was only half a lie. He would certainly do his best, that much was true. The lie part was that even his best wouldn’t be enough to get her out of jail. But he knew she wasn’t ready to hear that, not yet. “We need to talk about the case,” he told her instead, “so we can figure out our best chance of getting you out.” His father, long dead, had been a doctor, the old-fashioned kind. He’d never told his patients that they had a bellyful of inoperable cancer and were going to die from it. He told them they had “suspicious cells,” and that the radiation or chemotherapy he was sending them for was simply a “precautionary measure.” That was what he was doing with Samara now, he recognized. There were times when being a criminal defense lawyer turned you into something you weren’t in a hurry to write home about, he’d realized some years ago, before gradually coming to terms with the fact. Sometimes you donned the white hat and rode the white horse. But there were other times, times when, without quite breaking the rules, you bent them a little and adapted them to the situation. In the long run, you did what you had to do. Did he blame his father for having lied to his patients? He certainly had at the time, back when he was young and idealistic and had all the answers. Now, battle-tested and closing in on fifty himself, he knew enough to look at things a little differently.

“What do you want to hear?” Samara was asking him.

“Everything.”

“From the beginning?”

“From the beginning.”

8

PRAIRIE CREEK

“I was born in Indiana,” Samara said. “Prairie Creek. Nice name for a town, huh?”

Jaywalker nodded.

“It was a shithole.”

He made a written note on the yellow legal pad in front of him. It didn’t say Indiana, though, or Prairie Creek.

CLEAN UP HER MOUTH, it said.

“I never knew my father,” she said. “I grew up with my mother in a trailer, an old rusty thing set up on cinder blocks. My mom, well, she worked her ass off, I’ll say that much for her.”

“Is she still alive?”

That got a shrug, telling him that Samara either didn’t know or didn’t much care.

“I think she also sold her ass off, though I don’t know for sure. She was pretty, prettier’n me.”

Jaywalker tried picturing prettier than Samara, but didn’t know where to start.

“She wasn’t home much. Always working or whatever.” Leaving the whatever to hang in the air for a few beats. “I remember being left with babysitters a lot. Guys, mostly.”

“How did that go?”

Another shrug. “I learned a lot.”

“Like what?”

“How to do shots of beer. How to roll joints.”

“Anything else?”

Samara broke off eye contact, looked downward. She tried to shrug again, but this attempt didn’t come off with the same Who-the-fuck-cares? as the two previous ones. It seemed to Jaywalker that her lower lip was pouting more than ever, but maybe it was only the tilt of her head.

“Is it important?” she asked him.