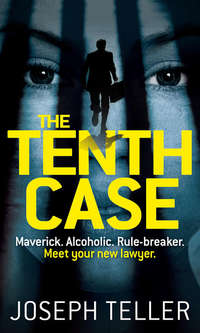

The Tenth Case

“It might be.”

She seemed to ponder that for a moment before looking up again. When she did, Jaywalker locked eyes with her. Trust me, he told her, without speaking the words out loud.

“Yeah,” she said, cocking her head slightly, but not looking away. “I learned how to give hand jobs and blow jobs, and how to thigh fuck.”

“Thigh fuck?” A new one for Jaywalker. He underlined CLEAN UP HER MOUTH, then underlined it a second time.

“Yeah, you know. Letting the guy stick it in between my legs. All the way up there, but not inside. I was too small for inside. Then, with my legs tight around the guy, I’d let him fuck away until—”

“Okay,” said Jaywalker, pretty much getting the picture.

“Get me out and I’ll show you.” Smiling now.

“How’d you do in school?” he asked her.

She laughed, whether at his abrupt change of subject or at the thought of her academic career. “How do drunk, stoned, fucked-up kids usually do?” she asked.

He took it as an answer.

“How far did you go?”

“I stuck around till the day after my fourteenth birthday. I wanted to see if I got any good presents.” Apparently she hadn’t. “I caught a bus to Terre Haute, then hitchhiked my way west, to Nevada. I wanted to be a showgirl or an actress, something like that. But you know what they told me? Too short. Too short. Now if I’d’a been too fat, or too thin, or too something-else-like-that, I could’a done something about it. But too short? What the fuck was I supposed to do about that?”

“So?”

“So I tended bar and waited tables, mostly.”

“Mostly?”

“And supplemented my income every now and then.”

“By doing what?”

“By doing what I would have done anyway. Only thing I did was when a guy wanted to give me something after, I took it.”

“And that something included money?”

“Sometimes.”

“Ever get arrested? Other than this and that DWI thing?” Her criminal record printout showed nothing else, but Jaywalker knew that there might be out-of-state cases, or arrests that hadn’t led to convictions that often wouldn’t show up.

“No.”

“Are you absolutely sure?”

A pause, then, “Maybe there was this one time in Reno for attempted soliciting. It was pure bullshit. I was standing in front of a club, smoking a cigarette. Some vice cop decided that meant I had to be hooking.”

Underneath CLEAN UP HER MOUTH, Jaywalker wrote WORK ON GETTING HER TO TELL THE TRUTH, and underlined it three times. “What happened to the case?” he asked.

“It was dismissed.”

“How much of a fine did you pay?”

“Fifty dollars.”

When a case was dismissed, there was no fine to pay. Jaywalker added an exclamation point to his latest reminder.

“Other arrests?”

“No.”

“Absolutely sure?”

“Yes!” she snapped. Then, “Sorry.”

“How did you meet Barry?”

She’d been working for tips off a phony driver’s license in Vegas, serving drinks to the rollers in one of the lounges in Caesars Palace. She was eighteen at the time. “It was like three o’clock in the morning, going into Sunday, and the crowd was beginning to thin out. I see this guy staring at me, I mean really staring. I bring him a drink, a Diet Coke. He tells me I’m the most beautiful thing he’s ever seen. Not the most beautiful person, the most beautiful thing. Shit, I should’a known right then. But being eighteen and dumb, I think it’s pure poetry. Know what I mean?”

Jaywalker nodded. He’d come up with worse lines in his day, though not by all that much.

“I go up to his room after I get off, and we talk. Talk. For like five hours I’m carrying on a conversation with a man who’s been to college, knows about politics and world affairs and wine and all sorts of other stuff. But he wants to know about me. Where I grew up, what it was like, why I ran away, what my hopes and dreams are. Hopes and dreams. And I’m telling him shit I wouldn’t tell my best friend, if I had one. Like I’m opening my heart to him.

“Eleven o’clock comes, and he’s got to go to a meeting. Asks me if he can kiss me. I say, ‘Sure.’ With that he touches me, barely touches me, with both hands on the sides of my face, and gives me the gentlest kiss in the world. No tongue, no open mouth, no grabbing. I gotta tell you, I felt like Madonna.”

Jaywalker was pretty sure he knew which one she was referring to.

“Anyway, he leaves, goes back to New York. But he keeps calling me, like every day, and sending me flowers. Next he asks me to come east to visit him. I tell him right, like I’ve got money for a bus ticket. He tells me that won’t be necessary, he’ll send one of his planes to get me. One of his planes. So I go to New York, and we get married eight months later.”

To Jaywalker, the segue seemed natural enough.

The fact that the marriage had survived for eight years was hardly testimony to its success. The place Samara had persuaded Barry to buy her before the first year was over was the four-story brownstone in the lower Seventies, between Park and Lexington. The city’s inflated real estate had driven up the asking price to close to five million dollars, but if Barry complained, it was to deaf ears. “He used to tip that much in a year,” according to Samara.

Within a few months she had basically set up residence in the town house. She continued to appear in public with Barry but made no secret of the fact that theirs had become an “open marriage,” a throwback phrase from an earlier generation. Still, there was no talk of divorce. Barry had been there and done that three times already, and apparently had no taste for a fourth go-round.

“But according to your statement to the police,” Jaywalker pointed out, “you admitted having fights, the two of you.”

“That was their word,” said Samara. “Fights.”

“And your word?”

“Arguments.”

“What did you argue about?”

“You name it, we argued about it. Money, sex, my driving, my clothes, my drinking, my language. Whatever couples argue about, I guess.”

A corrections officer came into the lawyers’ section of the room and asked for everyone’s attention. “Anyone who wants to make the one o’clock bus back,” he announced, “wind it up. You got ezzackly five minutes.”

Jaywalker looked at Samara. If she missed the one o’clock, it meant she’d be stuck in the building till after five, which could mean not getting back to Rikers before ten or eleven, and having to settle for a bologna or cheese sandwich instead of what passed for a hot meal. But Samara gave one of her patented shrugs. Jaywalker took it as a good sign that she was willing to make personal sacrifices in order to finish telling him her story.

He should have known better.

There was a lot of rustling in the room as other inmates rose to leave, and other lawyers gathered their papers and snapped their briefcases shut.

“Tell me about the month or so before Barry’s death,” he said.

“What about it?”

“What was going on? Any new arguments? Anything out of the ordinary?”

Samara seemed to think back for a moment. “Not really,” she said. “Barry was sick, and—”

“Sick?”

“He had the flu.” The way she spat out the word suggested that she’d had little sympathy for him. “He thought I should be around more. You know, to take care of him. I told him that’s what doctors are for, and hospitals. I mean, it’s not like he couldn’t afford it. Still, I did see a little more of him than usual.”

“Where?”

“His place, mostly. Mine, once or twice. Out, a couple of times. I don’t know.”

“And how did the two of you get along on those occasions?”

Two shrugs.

“What does that mean?” Jaywalker asked.

“We got along the same as always,” she said. “When we were apart, fine. When we were together, Barry always found a way to pick a fight.”

“A fight?”

“An argument. Jesus, you’re as bad as the cops.”

“Sorry,” said Jaywalker. “Tell me about the evening before you found out Barry had been killed. Your statement says you first denied seeing him, then admitted you’d gone to his place. Is that true?”

“Is what true?”

Objection sustained. Jaywalker gave Samara a smile, then broke it down to a series of single questions. “Did you go there?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Did you deny it to the detectives at first?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“I didn’t think it was any of their goddamned business.”

That was a pretty good answer, actually, if you took away the goddamned part. If believed, it showed that Samara hadn’t known about Barry’s murder. If believed. He made a note of it on his yellow pad.

“What caused you to change your story,” he asked, “and admit you’d been there?”

“They said they already knew. The old bat next door heard us arguing.”

“Were you?”

“Yeah.”

“What about?”

“Who remembers? Barry was still pissed off that I’d walked out of some opera a few nights earlier, leaving him sitting there. Maybe that was it.”

“Why had you done that?”

“Why? Why? Have you ever sat through five hours of some three-hundred-pound woman wearing a helmet, sweating like a pig and singing in German? Next to someone with the flu?”

“No,” Jaywalker had to admit.

“Try it sometime.”

“Tell me everything you remember about that last evening at Barry’s,” said Jaywalker. “What prompted you to go there in the first place?”

“Barry asked me to,” Samara said. “Otherwise I wouldn’t have. He said he wanted to talk to me about something, but it turned out to be some bullshit, something about how much I’d spent at Bloomingdale’s or something like that. Who remembers?”

“What else?”

“Nothing much. He’d ordered Chinese food, and we ate. I ate, anyway. He said he couldn’t taste anything, on account of being all clogged up, so he barely touched it. I remember that,’ cause I asked him if he was poisoning me.”

Jaywalker raised an eyebrow.

“It was a joke,” said Samara. “You know, like if I pour us each a glass of wine and tell you to drink up, but meanwhile I don’t touch mine?”

“What did Barry say to that?”

“He laughed. He knew it was a joke.”

“What else happened?”

“I don’t know,” Samara said. “He asked me if I wanted to make love. It was his expression for fucking. I said no, I didn’t want to catch whatever he had, thank you very much. I said I was tired and was leaving. He said, ‘Just like the other night at the opera?’ And that did it. I told him what he could with his fucking opera, and he told me I was a dumb something-or-other, and we went at it pretty good.”

“But just words?”

“Yeah, just words. Loud ones, but just words.”

“And then?”

“And then I left.”

“That’s it?”

“That’s it.”

“What time was it?”

“Who knows?” said Samara. “Eight? Eight-thirty?”

“Where’d you go?”

“Home.”

“Straight home?”

“Yeah.”

“How?”

“Cab.”

Jaywalker made a note to subpoena the Taxi and Limousine Commission records, see if they could come up with the cabdriver. If they found him and he remembered the fare, he might be able to remember whether Samara had seemed agitated or acted normally.

“Did anyone see you?” he asked. “Other than the doorman and the cabby?”

“Not that I know of.”

“What did you do when you got home?”

“You really want to know?”

Jaywalker nodded. His guess would’ve been that she’d run a load of laundry and taken a shower. You stabbed somebody in the heart, chances were you were going to get some blood on you.

“I really need to know,” he said.

“Fine,” she said, her eyes never leaving his. “I jerked off.”

Okay, not exactly what he’d expected to hear. Then again, the literature was full of accounts of serial killers describing how their crimes aroused them sexually and prompted them to masturbate, either right there at the scene or at home, shortly afterward. True, all of them were men, as far as Jaywalker could recall. But, hey, this was the twenty-first century, and having long held himself out as a supporter of equal rights for women, who was he to renege now?

“Do you have any idea,” he asked Samara, “who killed your husband?”

“No.”

“Can you think of anyone who might’ve wanted him out of the way?” As soon as he’d said the words, he regretted them. They sounded like something out of an old black-and-white movie from the forties.

“You don’t make billions of dollars,” said Samara, “without making enemies along the way.”

Come to think of it, she belonged in an old black-and-white movie from the forties.

“I only know one thing,” she added.

“What’s that?”

“I didn’t do it. You gotta believe me.”

“I do,” Jaywalker lied.

9

NICKY LEGS

That had been ten months ago, that first sit-down in which Samara had protested her innocence and Jaywalker had mumbled his “I do” with all the conviction of a shotgun groom. It had been two weeks before his appearance before the judges of the disciplinary committee, when he’d learned of his three-year suspension and begged to be permitted to complete work on his pending cases. He’d countered their offer to let him “dispose of” five with a list of seventeen, which they’d then pared down to ten.

Now, in June, with nine of those ten disposed of, Jaywalker found himself in the strangest of all positions, a criminal defense lawyer with only one criminal left to defend.

Why had he included Samara Tannenbaum in his must-keep list, when her case was barely two weeks old at that point and he had dozens of others in which he’d invested far more time, effort and emotion? To put it into the vernacular of modern mallspeak, it had been a no-brainer. First off, Samara’s was a murder case. Jaywalker had once heard a colleague refer to a murder charge as nothing but an assault case in which you knew the complainant wasn’t going to show up in court to testify against your client. Either the lawyer was joking, or he was a total jerk. Murder was like no other crime. There were longer trials, to be sure, and more complicated ones, and ones with lots more witnesses and paper and hearings and tape recordings and exhibits. There were crimes that carried equally severe sentences. Arson, for example, or kidnapping, or selling a couple of ounces of heroin or cocaine. Still, murder stood apart. Judges knew that, juries knew that and Jaywalker knew that. A life had been taken, the most important of the holy commandments had been broken, and the passion play that followed was almost biblical in its proportions. If for no other reason than that it was a murder charge, Samara’s case deserved to be on Jaywalker’s short list.

But there’d been other reasons, too.

By holding on to the case, Jaywalker knew that he would be able to keep the wolf from the door for as long as possible. With Samara insisting on her innocence, however ludicrously, came the promise of months of investigation, motions and preparation, followed by a trial and then, if she was convicted, a sentencing. If he strung it all out, it might even be long enough for his final act. He was tired, Jaywalker was. Twenty years of defending criminals might not seem like much to an outsider, but to Jaywalker, it had felt like an eternity. The thing about it was, you were always fighting. You fought prosecutors, cops and witnesses. You fought judges. You fought court officers and corrections officers. You fought your own clients, and your clients’ family and friends. And if you had your own family and friends—which Jaywalker, perhaps tellingly, had precious few of—you got around to fighting them, too, sooner or later.

There’d been a time when he’d laughed at the word burnout. Like when his daughter had called from college two months into her freshman year to report that she was burned out from all the stress and needed plane fare to come home over Thanksgiving. He’d sent her a check, of course, but he’d had a good laugh at her complaint. Now, after twenty years of almost ceaseless fighting, Jaywalker knew there was indeed such a thing as burnout.

If he played his cards right, he figured, he could ride this hand for a year or more, maybe even two or three, before they began his actual suspension. That would be enough. No reapplying, no promises to the Character and Fitness Committee to behave himself better next time around. They could pull his ticket and do whatever they wanted to with it at that point. He’d get a job, write a book, drive a cab, go on welfare, get food stamps, rob a bank. Whatever. So simply in terms of forestalling the inevitable for as long as possible, Samara’s case, coupled with her denial of her guilt, was an ideal one.

But if Jaywalker really wanted to be honest with himself, he knew there was more to it even than that. There was Samara herself.

From the moment he’d first seen her six years ago, when she’d come in on that drunk driving charge, he’d been swallowed whole by her dark eyes and pouting lower lip. Even as he’d fought to play the mature, steady defender to her reckless, impulsive child, from the beginning it had been she who’d owned him. Owned him in the sense that, try as he might, he could never take his eyes off her when he was in her presence. He’d dreamed of her at night and fantasized about her by day. Sexual fantasies, to be sure. But life-altering ones, as well. In one of his darker reveries, it had been the sudden, unexplained death of Samara’s older husband that had driven her headlong into Jaywalker’s comforting arms. So real and so elaborate had that particular scenario been that years later, when he first heard that Samara had been arrested for Barry’s murder, Jaywalker had been forced to wonder if he himself weren’t somehow complicit in the crime.

So the reasons were many why he’d hung on to her case, even at seventy-five dollars an hour. And now, as June gave way to July, it was all he had left, the only thing that stood between practicing his craft and being put out to pasture. And it represented his one last grand chance to overcome the impossible odds, slay the dragon, and win the dark-haired, dark-eyed princess of his dreams.

Why impossible odds?

Because in the ten months since he’d first sat down across from Samara in the counsel room to hear her say she hadn’t killed her husband, things had indeed gone as Jaywalker had suspected they would—from bad to worse to downright dreadful.

The progression had begun almost immediately. From the twelfth-floor counsel visit room, Jaywalker had ridden the elevator down to the seventh floor, where he’d paid a visit to Tom Burke.

“Hey, Jay. Howyadoon?”

A lot of people called him Jay. Not having a first name kind of limited their options.

“Okay, I guess,” said Jaywalker. “I’ve just spent the last three hours with Samara Tannenbaum.” It was true. After Samara’s denial of her guilt and his own assurance that he believed her, they’d talked for another hour and a half. If he’d been impressed with her willingness to miss the one o’clock bus back to Rikers, he was somewhat troubled by her evident need to keep the meeting going as long as possible.

“From what I hear,” said Burke, “people have paid good money to spend thirty minutes with her. But I’ll say this. She sure is good to look at.”

“That she is,” Jaywalker agreed.

“It’s a shame she’s a cold-blooded killer.”

Jaywalker said nothing. He was there to listen and, hopefully, to learn a thing or two, not to posture about his client’s innocence. Particularly when he himself was having trouble buying it.

“Did you read the stuff I gave you Friday?” Burke asked him.

“Yeah. And I appreciate your generosity.” Jaywalker wasn’t being facetious. They both knew Burke had handed over much more than the law required at such an early stage of the proceedings.

“Hey,” said Burke. “I got nothing to hide on this one. In my office, it’s what we call a slam dunk.”

“Why?”

“Why? I’ve got witnesses who put her there and have her arguing with the deceased at the time of death. I’ve got her false exculpatory statements, first that she wasn’t there, then that they didn’t fight. I’ve got the murder weapon hidden in her home. And I’ve got ten bucks that says that little dark-red stain on it is going to turn out to be a perfect DNA match with Barry’s blood.”

“No,” said Jaywalker. “I didn’t mean, Why is it a slam dunk? I meant, Why did she do it?”

Burke gave an exaggerated shrug. Jaywalker decided he could use a lesson or two on the art from Samara. “Hey,” said Burke, “why do seventy percent of murders happen? Two people who know each other get into an argument about some trivial piece of bullshit. They start swearing and calling each other names. Maybe they’ve been drinking, or smoking something. One thing leads to another. If there happens to be a gun around, or a knife…” He extended his arms, elbows bent slightly, palms turned upward, as if to say that in such situations, murder was all but inevitable, a part of the human condition.

“That’s it?”

“What are you looking for?” Burke asked. “A motive?”

“God forbid,” said Jaywalker. The prosecution was never required to come up with a motive; the most they were ever asked to prove was intent. They taught you the difference in law school. You shot or stabbed or clubbed someone to death with the intent to kill them. Whether your motive behind that intent happened to be greed, say, as opposed to revenge or sadism, didn’t matter.

Only it did matter, Jaywalker knew. Because if a crime didn’t make sense to him, it might not make sense to a jury, either.

“Tell you what,” said Burke, reading Jaywalker’s mind. “Give me two weeks, I bet I’ll have a motive for you. Want to go double or nothing on that ten bucks?”

“Sure,” said Jaywalker. “You’re on.”

It was less than two weeks later that Jaywalker found himself standing before the three disciplinary committee judges. So if now he needed yet another reason to include Samara’s name on his list, he had it: he had twenty bucks riding on the outcome.

With Samara indicted but yet to appear in Supreme Court for her arraignment, the case fell into a legal limbo of sorts. In terms of formal proceedings, nothing would happen for the time being. No written motions could be filed yet, no hearings could be asked for, no plea could even be entered. Before any of those things could take place, the case would first have to travel from the fourth floor of 100 Centre Street to the eleventh. In real time, such a journey might be expected to take two minutes, three if the elevators were out of order, a fairly regular occurrence. But in courthouse time, it took three weeks.

“Sorry, counselor,” the lower court judge would always say. “If I give you an earlier date, the papers won’t make it upstairs in time.”

“Give ’em to me,” Jaywalker had pleaded over the years. “I’ll have ’em up there before you can unzip your robe.” But all it ever got him were unamused stares and even longer adjournments. To paraphrase an old saying, judges don’t get mad, they get even.

That said, the fact that Samara’s case was stalled in traffic for the next three weeks didn’t mean it was time for Jaywalker to sit on his hands or catch up on old issues of The New Yorker. Quite the opposite.