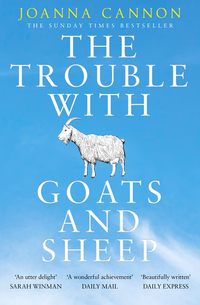

The Trouble with Goats and Sheep

‘He didn’t keep Mrs Creasy safe, though, did he?’

I watched bumble bees drift between the sunflowers. They explored each one, dipping into the centre, searching and inspecting, until they reappeared in the daylight, dusted in yellow and drunk with achievement.

And it all became so obvious. ‘I know what we’re going to do with the summer holidays,’ I said, and got to my feet.

Tilly looked up. She squinted at me and shielded her eyes from the sun. ‘What?’

‘We’re going to make sure everyone is safe. We’re going to bring Mrs Creasy back.’

‘How are we going to do that?’

‘We’re going to look for God,’ I said.

‘We are?’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘we are. Right here on this avenue. And I’m not giving up until we find Him.’

I held out my hand. She took it and I pulled her up next to me.

‘Okay, Gracie,’ she said.

And she put her sou’wester back on and smiled.

Number Six, The Avenue

27 June 1976

It was Are You Being Served? on a Monday, The Good Life on a Tuesday, and The Generation Game on a Saturday. Although for the life of her, Dorothy couldn’t see what people found funny about Bruce Forsyth.

She tried to remember them, like a test, as she did the washing-up. It took her mind off the church hall, and the look on John Creasy’s face, and the spidery feeling in her chest.

Monday, Tuesday, Saturday. She usually liked washing up. She liked to watch the garden and idle her mind, but today the weight of the heat pressed against the glass and made her feel as though she were looking out from a giant oven.

Monday, Tuesday, Saturday.

She could still remember, although she wasn’t taking any chances. They were all circled in the Radio Times.

Harold became very irritable if she asked him something more than once.

Try to keep it in your head, Dorothy, he told her.

When Harold became angry, he could fill a room with his own annoyance. He could fill their sitting room, and the doctor’s surgery. He could even fill an entire supermarket.

She tried very hard to keep things in her head.

Sometimes, though, the words escaped her. They hid behind other words, or they showed a little of themselves, and then disappeared back into her mind before she had a chance to catch them.

I can’t find my … she would say, and Harold would throw choices at her like bullets. Keys? Gloves? Purse? Glasses? and it would make the word she wanted disappear even more.

Cuddly toy, she said one day, to make him laugh.

But Harold didn’t laugh. Instead, he stared at her as though she had walked into the conversation uninvited, and then he had closed the back door very quietly and started mowing the lawn. And somehow the quietness filled a room even more than the anger.

She folded the tea towel and put it on the edge of the draining board.

Harold had been quiet since they’d got back from church. He and Eric had deposited John Creasy somewhere, although Lord knows where, she hadn’t even dared ask, and he had sat down and read his newspaper in silence. He had eaten his dinner in silence, and dropped gravy down his shirt front in silence, and when she asked him if he wanted mandarin segments with Ideal milk for afterwards, he had only nodded at her.

When she put it down in front of him, he said the only sentence to come out of his mouth all afternoon. These are peaches, Dorothy.

It was happening all over again. It ran in families, she’d read it somewhere. Her mother ended up the same way, kept being found wandering the streets at six in the morning (postman, nightdress) and putting everything where it didn’t belong (slippers, breadbin). Mad as a box of frogs, Harold had called her. She was around Dorothy’s age when she first started to lose her mind, although Dorothy always thought losing your mind was such a strange phrase. As if your mind could be misplaced, like a set of house keys, or a Jack Russell terrier, as if it was more than likely your own fault for being so bloody careless.

They’d put her mother in a home within weeks. It was all very quick.

It’s for the best, Harold had said.

He’d said it each time they went to visit.

After he’d eaten his peaches, Harold had settled himself on the settee and fallen asleep, although how anyone could sleep in this heat was beyond her. He was still there now, his stomach rising and falling as he shifted in between dreams, his snoring keeping time with the kitchen clock, and plotting out the afternoon for them both.

Dorothy took the remains of their silent meal and emptied it into the pedal bin. The only problem with losing your mind was that you never lost the memories you wanted to lose. The memories you really needed left first. Her foot rested on the pedal, and she looked into the waste. No matter how many lists you wrote, and how many circles you made in the Radio Times, and no matter how much you practised the words over and over again, and tried to fool people, the only memories that didn’t leave were the ones you wish you’d never made in the first place.

She reached into the rubbish and lifted a tin out of the potato peelings. She stared at it.

‘These are peaches, Dorothy,’ she said to an empty kitchen. ‘Peaches.’

She felt the tears before she even knew they had happened.

*

‘The problem, Dorothy, is that you think too much.’ Harold’s gaze never left the television screen. ‘It’s not healthy.’

Evening had tempered the sun, and a wash of gold folded across the living room. It drew the sideboard into a rich, dark brandy and buried itself in the pleats of the curtains.

Dorothy picked imaginary fluff from the sleeve of her cardigan. ‘It’s difficult not to think about it, Harold, under the circumstances.’

‘This is completely different. She’s a grown woman. Her and John have probably just had some kind of tiff and she’s cleared off for a bit to teach him a lesson.’

She looked over at her husband. The light from the window gave his face a faint blush of marzipan. ‘I only hope you’re right,’ she said.

‘Of course I’m right.’ His stare was still fastened to the television screen, and she watched his eyes flicker as the images changed.

It was Sale of the Century. She should have known better than to speak to Harold whilst he was occupied with Nicholas Parsons. It might have been best to try and fit the conversation into an advert break, but there were too many words and she couldn’t stop them climbing into her mouth.

‘The only thing is, I saw her. A few days before she disappeared.’ Dorothy cleared her throat, even though there was nothing to clear. ‘She was going into number eleven.’

Harold looked at her for the first time. ‘You never told me.’

‘You never asked,’ she said.

‘What was she doing going in there?’ He turned towards her, and his glasses fell from the arm of his chair. ‘What could they possibly have to say to each other?’

‘I have no idea, but it can’t be a coincidence, can it? She speaks to him, and then a few days later, she vanishes. He must have said something.’

Harold stared at the floor, and she waited for his fear to catch up with hers. In the corner, the television churned the laughter of strangers out into their living room.

‘What I don’t understand’, he said, ‘is how he could stay on the avenue, after everything that happened. He should have moved on.’

‘You can’t dictate to people where they live, Harold.’

‘He doesn’t belong here.’

‘He’s lived at number eleven all his life.’

‘But after what he did?’

‘He didn’t do anything.’ Dorothy looked at the screen to avoid Harold’s eyes. ‘They said so.’

‘I know what they said.’

She could hear him breathing. The wheeze of warm air moving through tired lungs. She waited. But he turned to the television and straightened his spine.

‘You’re just being hysterical, Dorothy. All that’s over and done with. It was ten years ago.’

‘Nine, actually,’ she said.

‘Nine, ten, what does it matter? It’s all in the past, except every time you start talking about it, it stops being in the past and starts being in the present again.’

She gathered the material of her skirt into folds and let them fall between her hands.

‘Would you stop fidgeting, woman.’

‘I can’t help myself,’ she said.

‘Well, go and do something productive. Go and have a bath.’

‘I had a bath this morning.’

‘Well, go and have another one,’ he said, ‘you’re putting me off the questions.’

‘What about saving water, Harold?’

But Harold didn’t reply. Instead of replying, he picked at his teeth. Dorothy could hear him. Even over Nicholas Parsons.

She smoothed down her hair and her skirt. She took a deep breath to suffocate her words, and then she stood up and walked from the room. Before she closed the door, she looked back.

He had turned away from the television, and was staring through the window – past the lace of the curtains, across the gardens and the pavements, to the front door of number eleven.

His glasses still lay at his feet.

*

Dorothy knew exactly where she’d hidden the tin.

Harold never went into the back bedroom. It was a holding place. A waiting room for all the things she no longer needed but couldn’t bear to lose. He said the thought of it gave him a headache. As the years turned, the room had grown. Now the past pushed into corners and reached to the ceiling. It stretched along the windowsill and touched the skirting boards, and it allowed Dorothy to hold it in her hands. Sometimes, remembering wasn’t enough. Sometimes, she needed to carry the past with her to be sure she was a part of it.

The room trapped summer within its walls. It held Dorothy in an airless museum of dust and paper, and she felt the sweat bleed into her hairline. The sound of the television crept through the floorboards, and she could picture Harold beneath her feet, answering questions and picking at his teeth.

The tin sat between a pile of blankets her mother had crocheted and some crockery left over from the caravan. She could see it from the doorway, as though it had waited for her, and she kneeled on the carpet and pulled it free. Around the edge were photographs of biscuits to tempt you inside, pink wafers and party rings and Jammie Dodgers, all joining cartoon hands and dancing with cartoon legs, and she held on to them as she lifted the lid away.

The first thing she saw was a raffle ticket from 1967 and a collection of safety pins. There were Harold’s tarnished cufflinks and a few escaped buttons, and the cutting about her mother’s funeral from the local paper.

Passed away peacefully, it said.

She hadn’t.

But beneath the pins and the grips and the buttons was what she had come for. Kodak envelopes, fattened with time. Harold didn’t believe in photographs. Mawkish, he called them. Dorothy didn’t know anyone else who used the word ‘mawkish’. There were very few pictures of Harold. There was an occasional elbow at a dinner table, or trouser leg on a lawn, and if anyone had managed to capture his face in the frame, he wore the expression of someone who had been the victim of trickery.

She searched through the packets. Most of the photographs were rescued from her mother’s house. People she didn’t know, held within white, serrated edges, sitting in gardens she didn’t recognize and rooms she had never visited. There were Georges and Florries, and lots of people called Bill. They had written their names on the back, perhaps hoping that, if their identity were known, they would somehow be better remembered.

There were few photographs of her own – an infrequent Christmas gathering, a meal with the Ladies’ Circle. A photograph of Whiskey fell to the carpet, and she felt her throat fill.

He had never come home.

Just get another cat, Harold had said.

It was the closest she had ever come to losing her temper.

The photograph she wanted was at the bottom, a weight of memories pressed upon it. She had to see. She had to be sure. Perhaps, over the years, the past had become misshapen. Perhaps time had stretched their part in it, and bloated her conscience. Perhaps, if she could see the faces again, she would recognize their harmlessness.

They looked up at her from a table at the British Legion. It was before everything happened, but she was sure it was the same table – the table where the decision had been made. Harold sat next to her, and they both stared into the lens with troubled eyes. The photographer had caught them by surprise, she remembered that, someone from the town paper wanting pictures for an article on local colour. Of course, they never used it. John Creasy stood behind them, his hands pushed into his pockets, looking out from under a Beatles fringe. Sitting in front of John was that daft clown Thin Brian, with a pint glass in his hand, and Eric Lamb was opposite Harold. Sheila Dakin was on the end – all eyelashes and Babycham.

Dorothy looked at their faces, hoping to see something else.

There was nothing. They were exactly as she had left them.

It was 1967. The year Johnson sent thousands more to die in Vietnam. The year China made a hydrogen bomb, and Israel fought a six-day war. The year people marched and shouted, and waved banners about what they believed in.

It was a year of choices.

She wished she had known then that one day she would be staring back at herself, wishing that the choice they had made had been a different one. She turned the photograph over. There were no names. After all that had happened, she was certain none of them would care to be remembered.

‘Whatever are you doing?’

Harold’s footsteps weren’t usually so discreet. She turned away from him and tucked the photograph into her waistband.

‘I’m going over a few things.’

He leaned against the door frame. Dorothy wasn’t sure when it happened, but Harold had become old. The skin on his face had thinned to a lacquer, and his posture was bowed and curved, as though he were slowly returning to the womb.

‘So, why have you buried yourself in here, Dorothy?’

She looked straight into his eyes and saw his mind stumble.

‘I’m making …’ she said, ‘I’m making …’

‘Headway?’ Harold peered into the room. ‘A mess? A nuisance of yourself?’

‘A choice.’ Dorothy smiled up at him. ‘I’m making a choice.’

And she watched as he wiped sweat from his temple with the sleeve of his shirt.

*

When Harold went back downstairs, Dorothy walked on to the landing and looked at the photograph again. The smell came to her first, a smell that seemed to live on the avenue for weeks afterwards, held in a bite of December frost. Sometimes she thought she could still smell it now, even after all this time. She would be walking along the pavement, wandering around in her own thoughts, and it would creep up on her again. As if it had never really disappeared, as if it had been left there on purpose to remind them all. That night, she had stood where she was standing now, and she had watched it all unfold. She had replayed that scene to herself so many times, perhaps hoping something might change, that she would be able to let it go, but it was a night that had nailed itself to her memory. And she had known even then, even as she’d watched, that there would be no going back.

21 December 1967

Sirens hammer into the road, drawing the avenue from its sleep. Lights fizz and tick, and aquariums of people look out into the night. Dorothy watches from the landing. The banister digs into her bones as she leans forward, but this is the window with the best view, and she leans a little more. As she does, the bells of the siren stop and the fire engine empties men on to the street. She tries to listen, but the glass dulls their voices, and the only sound she hears is air moving through her throat, and the stamp of a pulse in her neck.

Ferns of ice grow at the corners of the windows, and she has to peer around them to see properly. There are hoses twisting across pavements, and rivers of light shining into the black. It feels unreal, theatrical, as though someone is staging a play in the middle of the avenue. Across the road, Eric Lamb opens his front door, pulling on a jacket, shouting back before he runs on to the street, and all around her, windows catch and push, spilling breath into the darkness.

She calls to Harold. She has to call several times, because his dreams are like cement. When he does appear, he has the frayed edges of someone who has been shocked into consciousness. He wants to know what’s going on, and he shouts the question at her, even though he is standing three feet away. She can see the skin of sleep in the corners of his eyes, and the journey of the pillow across his cheek.

She turns back to the window. More doors have opened, more people have appeared. Above the smell of the house, above the polished windowsills and the Fairy Liquid sink, she imagines she can sense the smoke, sliding in through the cracks and the splinters, and finding its way through the bricks.

She looks back at Harold.

‘I think something very bad has happened,’ she says.

*

They reach the garden. John Creasy calls across the avenue, but his voice is lost in the churn of the engine and the punch of boots on the concrete. Dorothy peers through the dark towards the bottom of the road. Sheila Dakin is standing on the lawn, feeding her hands into her face, the wind whipping at her dressing gown, smacking the material against her legs like a flag. Harold tells Dorothy to stay where she is, but it feels as though the fire has a magnetic field, and everyone is pulled closer, drawn along paths and pavements. The only one who is still is May Roper. She stands in her doorway, held there by the light and the noise and the smell. Brian catches her as he rushes past, but she barely seems to notice.

The firemen work like machinery, forming links of a chain which drags water from the earth. There is an arc of sound. An explosion. Harold is shouting to Dorothy to get back inside, but she moves a little closer instead. She watches Harold. He is too interested in what’s happening to notice, and she edges her way next to the wall. She just needs to see for a moment. To find out if it’s really happened.

She reaches the far end of the garden, when a fireman begins sweeping the air with his arms, forcing them back like puppets, and they collect in the middle of the avenue, knotted together against the frost.

The fireman is shouting questions. How many people live in the house?

They all answer at once, and their voices are smeared, taken by the wind.

The fireman scans their faces and points at Derek. ‘How many?’ he says again, his mouth shaping around the words.

‘One,’ he shouts, ‘just one.’ Derek looks back at his own house, and Dorothy follows his gaze. Sylvia stands at the window, Grace in her arms. Sylvia watches them, then turns away, holding the child’s head against her skin. ‘His mother lives in a nursing home, but he’s taken her away for Christmas,’ Derek says. ‘So it’s empty.’ The fireman is already running back and Derek’s words are wasted to the darkness.

A roll of smoke unfolds towards the sky. It loses itself against the black, whispering edges caught against a bank of stars before it feathers into nothing. Harold finds Eric’s eyes, and Eric shakes his head, a brief movement, almost nothing. Dorothy catches it, but looks away, back to the grip of the noise and the smoke.

None of them notice him, not to begin with. They are too captured by the flames, watching the darts of orange and red that fasten and catch in the windows. It’s Dorothy who sees him first. Her shock is soundless, static, but still it finds each of them. It stumbles around the group, until they all turn from number eleven and stare.

Walter Bishop.

The wind slips inside his coat and lifts the collar. It takes spirals of his hair and tries to cover his eyes. His lips are moving, but the words aren’t yet ready to leave. There is a carrier bag. It falls from his hand and a tin skittles across the pavement and into the gutter. Dorothy lifts it back and tries to return it to him.

‘Everyone thought you’d gone away with your mother,’ she says, but Walter doesn’t hear.

There are shouts from the house, carried across the avenue, and one fireman’s voice lifts above the rest.

There’s someone in there, it says. There’s someone in the house.

They all turn from the fire to look at Walter.

‘Who’s inside?’ It’s the question in everyone’s eyes, but it’s Harold who gives it a voice.

At first, Dorothy doesn’t think Walter has even heard the question. His gaze doesn’t move from the slurry of black smoke, which has begun to pour from the windows of his house. When he finally replies, his voice is so soft, so whispered, they all have to lean forward to listen.

‘Chicken soup,’ he says.

Harold frowns. Dorothy can see all the wrinkles of the future pinch together on his forehead.

‘Chicken soup?’ The wrinkles become even deeper.

‘Oh yes.’ Walter’s eyes don’t move from number eleven. ‘It works wonders for the flu. Terrible thing, isn’t it, the flu?’

They all nod, like ghostly marionettes in the darkness.

‘We’d only just got to the hotel when she took ill. I said to her, Mother, I said, when you’re under the weather, what you need is your own bed. And so we turned around and came home again.’

And all the marionette eyes stare at Walter’s first-floor window.

‘And she’s up there now?’ says Harold, ‘your mother?’

Walter nods. ‘I couldn’t take her back to the nursing home, could I? Not in that state. So I put her to bed and went to ring for the doctor.’ He looks at the tin Dorothy handed back to him. ‘I wanted to explain to him I was giving her the soup, as he advised. They put so many additives in these things now. You can’t be too careful, can you?’

‘No,’ says Dorothy, ‘you can’t be too careful.’

The smoke creeps across the avenue. Dorothy can taste it in her mouth. It blends with the fear and the frost, and she pulls her cardigan a little closer to her chest.

*

Harold walks into the kitchen through the back door. Dorothy knows he has something to tell her, because he never uses the back door unless it’s an emergency or he is wearing his wellington boots.

She looks up from her crossword and waits.

He moves around the work surfaces, lifting things up unnecessarily, opening cupboard doors, looking at the bottom of crockery, until he can’t hold on to the words any longer.

‘It’s awful in there,’ he says, as he replaces a mug on the mug tree. ‘Awful.’

‘You’ve been inside?’ Dorothy puts down her pen. ‘Are you allowed to go inside?’

‘The police and the fire service haven’t been there for days. No one said we couldn’t go inside.’

‘Is it safe?’

‘We didn’t go upstairs.’ He finds a packet of bourbons she had deliberately hidden behind the self-raising flour. ‘Eric didn’t think it was respectful, you know, under the circumstances.’

Dorothy doesn’t think it’s respectful rummaging around in the downstairs either, but it’s easier to say nothing. If you challenge Harold, he spends days justifying himself, like turning on a tap. She had wanted to go in there herself. She even got as far as the back door, but she’d changed her mind. It probably wouldn’t be wise, under the circumstances. Harold, however, had the self-discipline of a small toddler.