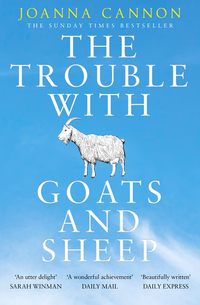

The Trouble with Goats and Sheep

‘What’s going on here, then?’ he said.

Mrs Forbes put herself back on the mantelpiece and spun round.

‘Grace and Tilly are Brownies.’ Her eyes were so bright, they were almost enamelled. ‘They’re here to lend …’ she faltered.

He folded his forehead into a frown and put his hands on his hips. ‘A book? Money? A cup of sugar?’

Mrs Forbes was hypnotized, and she wrapped the duster around her fingers until they became mottled with white.

‘To lend …’ Mrs Forbes repeated the words.

Mr Forbes continued to stare. I could hear his dentures click against the roof of his mouth.

‘A hand,’ said Tilly.

‘That’s right. A hand. They’re here to lend a hand.’

She unwound the duster, and I heard the air leave her lungs in little pieces.

Mr Forbes grunted.

He said as long as that’s all it is, and does Sylve know she’s here, and Mrs Forbes nodded so vigorously the crucifix around her neck did a little dance on her collarbone.

‘I’m going to post my letter,’ said Mr Forbes. ‘If we wait for you to do it, I’ll miss the second collection. I just need to find out where you’ve hidden my shoes.’

Mrs Forbes nodded again, and the crucifix nodded along with her, even though Mr Forbes had long since disappeared from the doorway.

‘My teachers do that to me all the time,’ said Tilly.

‘Do what, dear?’

‘Throw words at me until I get confused.’ Tilly picked garibaldi crumbs from the carpet and lifted them on to the plate. ‘It always makes me feel stupid.’

‘It does?’ said Mrs Forbes.

‘I’m not, though.’ Tilly smiled.

Mrs Forbes smiled back. ‘Do you enjoy school, Tilly?’ she said.

‘Not really. A lot of the girls don’t like us very much. Sometimes we’re bullied.’

‘They hit you?’ Mrs Forbes’ hand flew to her mouth.

‘Oh no, they don’t hit us, Mrs Forbes.’

‘You don’t always have to hit people,’ I said, ‘to bully them.’

Mrs Forbes reached for the nearest chair and lowered herself into it. ‘I expect you’re right,’ she said.

I was about to speak when Mr Forbes came back into the room. He was still wearing his shorts, but he had added a flat cap and a pair of sunglasses, and he was carrying a letter. He reminded me of my father. Whenever it became hot, he swapped his trousers for shorts, but everything else he kept exactly the same.

Mr Forbes placed his letter on the sideboard, and sat on the sofa with such force, the aftershock almost suspended Tilly in mid-air. He began tying his shoes, tugging at the laces until little fibres of fabric hovered in the space above his fingers. I stood up to give his legs more privacy.

‘So you can cross this off your list for a start, Dorothy,’ he was saying. ‘Although there’s plenty more to be getting on with.’

He looked over at me. ‘Will you be staying long?’ he said.

‘Oh no, Mr Forbes. Not long at all. We’ll be gone as soon as we’ve lent a hand.’

He looked back at his feet and grunted again. I wasn’t sure if he was approving of me or the tightness of his shoelaces.

‘She gets very easily distracted, you see.’ He nodded at Mrs Forbes with the brim of his cap. ‘It’s her age. Isn’t it, Dorothy?’ He made a winding motion at the side of his temple.

Mrs Forbes smiled, but it sat on her mouth at half-mast.

‘Can’t keep a thing in her head for more than five minutes.’ He spoke behind the back of his hand, like a whisper, but the volume of his voice remained exactly the same. ‘Losing her marbles, I’m afraid.’

He stood, and then bent very theatrically to adjust his socks. Tilly edged to safety at the far end of the settee.

‘I’m off to the post box.’ He marched towards the hall. ‘I shall be back in thirty minutes. Try not to get yourself in a muddle whilst I’m gone.’

He had vanished from the doorway before I realized.

‘Mr Forbes.’ I had to shout to make him hear.

He reappeared. He didn’t look like the kind of person who was used to being shouted at.

I handed him the envelope. ‘You’ve forgotten your letter,’ I said.

Mrs Forbes waited until the front door clicked shut, and then she began to laugh. Her laughing made me and Tilly laugh as well, and the rest of the world seemed to creep back into the room again, as if it wasn’t quite as far away as I thought.

Whilst we were laughing, I looked at Mrs Forbes, and I looked over at the girl on the mantelpiece, who laughed with us through a corridor of time, and I realized that they were a perfect match after all.

*

‘I didn’t know we’d actually have to do actual housework,’ said Tilly.

Mrs Forbes had left us tied into aprons up to our armpits. Tilly stood on the far side of the room, rubbing Brasso into a sleeping West Highland white terrier.

‘It’s important that we don’t arouse suspicion,’ I said, and took the last garibaldi back to the settee.

‘But do you think God is here?’ Tilly peered at the dog and ran the duster over its ears. ‘If God keeps everyone safe, do you think he’s keeping Mrs Forbes safe as well?’

I thought about the cross around Mrs Forbes’ neck. ‘I hope so,’ I said.

Mrs Forbes returned to the room with a new packet of garibaldis. ‘What do you hope, dear?’

I watched her empty them on to the plate. ‘Do you believe in God, Mrs Forbes?’ I said.

‘Of course.’

She didn’t hesitate. She didn’t look at the sky or at me, or even repeat the question back again. She just carried on rearranging biscuits.

‘How can you be so sure?’ said Tilly.

‘Because that’s what you do. God brings people together. He makes sense of everything.’

‘Even the bad things?’ I said.

‘Of course.’ She looked at me for a moment, and then returned to the plate.

I could see Tilly beyond Mrs Forbes’ shoulder. Her polishing had become slow and deliberate, and she willed a whole conversation at me with her eyes.

‘How can God make sense of Mrs Creasy disappearing?’ I said. ‘For example.’

Mrs Forbes stepped back, and a mist of crumbs fell to the carpet.

‘I’ve no idea.’ She folded the empty packet between her hands, even though it refused to become smaller. ‘I’ve never even spoken to the woman.’

‘Didn’t you meet her?’ I said.

‘No.’ Mrs Forbes twisted the packet around her ring finger. ‘They only moved into the house a little while ago, after John’s mother died. I never had the chance.’

‘I just wonder why she vanished?’ I edged the sentence towards her, like a dare.

‘Well, it was nothing to do with me, I didn’t say a word.’ Her voice had become spiked and feverish, and the sentence rushed from her mouth in order to escape.

‘What do you mean, Mrs Forbes?’ I looked at Tilly, and Tilly looked at me and we both frowned.

Mrs Forbes sank on to the settee.

‘Ignore me, I’m getting muddled.’ She patted the back of her neck, as if she was checking to see that her head was still firmly attached. ‘It’s my age.’

‘We just can’t understand where she’s gone,’ I said.

Mrs Forbes smoothed down the tassels on one of the cushions. ‘I’m sure she’ll return in good time,’ she said, ‘people usually do.’

‘I hope she does.’ Tilly untied the apron from under her arms. ‘I liked Mrs Creasy. She was nice.’

‘I’m sure she was.’ Mrs Forbes fiddled at the cushion. ‘But I’ve never spent any time in that woman’s company, so I couldn’t really say.’

I moved the garibaldis around on the plate. ‘Perhaps someone else on the avenue might know where she’s gone.’

Mrs Forbes stood up. ‘I very much doubt it,’ she said. ‘The reason Margaret Creasy disappeared is nothing to do with any of us. God works in mysterious ways, Harold was right. Everything happens for a reason.’

I wanted to ask her what the reason was, and why God had to be so mysterious about his work, but Mrs Forbes had taken the list out of her pocket.

‘Harold will be back soon. I’d better get on,’ she said. And she began running her finger down the lines of blue ink.

*

We walked back along the avenue. The weight of the sky pressed down on us as we pulled our legs through the heat. I stared at the hills which overlooked the town, but it was impossible to see where they began and where the sky ended. They were welded together by the summer, and the horizon shimmered and hissed and refused to be found.

Somewhere beyond the gardens, I could hear the sound of a Wimbledon commentary drifting from a window.

Advantage, Borg. And the distant flutter of applause.

The road was deserted. The beat of an afternoon sun had hurried everyone indoors to fan themselves with newspapers and rub Soltan into their forearms. The only person who remained was Sheila Dakin. She sat on a deckchair on the front lawn of number twelve, arms and legs spread wide, her face stretched towards the heat, as though someone had pegged her out as a giant, mahogany sacrifice.

‘Hello, Mrs Dakin,’ I shouted across the tarmac.

Sheila Dakin lifted her head, and I saw a trail of saliva glisten at the edge of her mouth.

She waved. ‘Hello, ladies.’

She always called us ladies, and it turned Tilly’s face red and made us smile.

‘So God is at Mrs Forbes’ house,’ said Tilly, when we had stopped smiling.

‘I believe he is.’ I pulled Tilly’s sou’wester down at the back, to cover her neck. ‘So we can say for definite that Mrs Forbes is safe, although I’m not very sure about her husband.’

‘It’s just a pity she never met Mrs Creasy, she could have given us some clues.’ Tilly kicked at a loose chipping, and it coasted into a hedge.

I stopped walking so suddenly, my sandals skidded dust on the pavement.

Tilly looked back. ‘What’s the matter, Gracie?’

‘The picnic,’ I said.

‘What picnic?’

‘The photograph of the picnic on the mantelpiece.’

Tilly frowned. ‘I don’t understand?’

I stared at the pavement and tried to think backwards. ‘The woman,’ I said, ‘the woman.’

‘What woman?’

‘The woman sitting next to Mrs Forbes at the picnic.’

‘What about her?’ said Tilly.

I looked up and straight into Tilly’s eyes. ‘It was Margaret Creasy.’

Number Two, The Avenue

4 July 1976

Brian sang to the hall mirror as he tried to find the parting in his hair. It was a little tricky, as his mother had insisted on buying a starburst design, and it was more burst than glass, but if he bent his knees slightly and angled his head to the right, he could just about fit his whole face in.

His hair was his best feature, his mother always said. Now girls seemed to like men’s hair a little longer, he wasn’t so sure. His only ever got as far as the bottom of his jaw and then it seemed to lose interest.

‘Brian!’

Perhaps if he tucked it behind his ears.

‘Brian!’

Her shouting tugged on him like a lead. He pushed his head around the sitting-room door.

‘Yes, Mam?’

‘Pass us that box of Milk Tray, would you? My feet are playing me up something chronic.’

His mother lay on a sea of crochet, her legs wedged on to the settee, rubbing at her bunions through a pair of tights. He could hear the static.

‘It’s the bloody heat.’ Her face was pinched into lines, the air in her cheeks filled with concentration.

‘There! There!’ she stopped rubbing and pointed at the footstool, which, in the absence of her feet, had become a home for the TV Times and her slippers, and a spilled bag of Murray Mints. She took the Milk Tray from him and stared into the box, with the same level of concentration as someone who was trying to answer an especially difficult exam question.

She pushed an Orange Creme into her mouth and frowned at his leather jacket. ‘Off out, are you?’

‘I’m going for a pint with the lads, Mam.’

‘The lads?’ She took a Turkish Delight.

‘Yes, Mam.’

‘You’re forty-three, Brian.’

He went to run his fingers through his hair, but remembered the Brylcreem and stopped himself.

‘Do you want me to ask Val to fit you in for a trim next time she comes round?’

‘No thanks, I’m growing it. The girls like it longer.’

‘The girls?’ She laughed and little pieces of Turkish Delight swam around on her teeth. ‘You’re forty-three, Brian.’

He shifted his weight and the leather jacket creaked at his shoulders. He’d bought it from the market. Probably wasn’t even real leather. Probably plastic, pretending to be leather, and the only person who was fooled was the idiot wearing it. He pulled at the collar and it crackled between his fingers.

His mother’s throat rose and fell with Turkish Delight, and he watched her dig her tongue around in her back teeth to make sure she’d definitely got her money’s worth.

‘Empty that ashtray before you go. There’s a good boy.’

He picked up the ashtray and held it at arm’s length, like an uncertain sculpture, a cemetery of cigarettes, each dated with a different colour of lipstick. He watched the ones at the edge tilt and waver as he carried it across the room.

‘Not the fireplace! Take it to the outside bin.’ She sent her instructions through a Lime Barrel. ‘It’ll stink the house out if you leave it in here.’

A curl of smoke twisted from somewhere deep in the mountain of fag ends. He thought he’d imagined it at first, but then the smell brushed at his nostrils.

‘You want to be careful.’ He nodded at the ashtray. ‘This is how fires start.’

She looked over at him and looked back at the box of Milk Tray.

Neither of them spoke.

He nudged around, and found the glow of a tip in the ash. He pinched at it until it flickered and the pleat of smoke stuttered and died. ‘It’s out now,’ he said.

But his mother was lost to the chocolates, gripped by bunions and Orange Cremes and the film now starting on BBC2. He knew she would be exactly the same when he returned from the Legion. He knew she would have pulled the blanket over her legs, and the Milk Tray box would be massacred and left to the carpet, and the television would be playing out a conversation with itself in the corner. He knew that she would not have risked moving from the edges of her crocheted existence. A world within a world, a life she had embroidered for herself over the past few years, which seemed to shrink and tighten with each passing month.

The avenue was silent. He pulled the lid from the dustbin and tipped the cigarettes inside, sending a cloud of ash into his face. When he had finished coughing and swiping at the air, and trying to find his next breath, he looked up and saw Sylvia in the garden of number four. Derek wasn’t with her – or Grace. She was alone. He rarely saw her alone, and he dared to watch for a moment. She hadn’t looked up. She was picking at weeds, throwing them into a bucket and brushing the soil from her hands. Every so often, she straightened her back, and gathered her breath and wiped her forehead with the back of a hand. She hadn’t changed. He wanted to tell her, but he knew it would only lead to more trouble.

He felt a line of sweat edge into his collar. He didn’t know how long he’d been watching, but she looked up and saw him. She lifted her hand to wave, but he turned just in time and got back inside.

He put the ashtray on the footstool.

‘Make sure you’re home by ten,’ his mother said, ‘I’ll need my ointment.’

The Royal British Legion

4 July 1976

The Legion was empty, apart from the two old men in the corner. Every time Brian saw them, they were sitting in the same place, and wearing the same clothes, and having the same exchange. They looked at each other as they spoke, but had two separate conversations, each man lost in his own words. Brian adjusted his eyes after the walk down. It was cooler in here, and darker. Summer soaked into the flocked walls and the polished wood. It was swallowed by the cool slate of the snooker table, and fell into the thread of the carpet, worn down by heavy conversation. The Legion didn’t have a season. It could have been the middle of winter, except for the sweat that caught the edge of Brian’s shirt and the pull of walking in his legs.

Clive sat on a stool at the end of the bar, feeding crisps to a black terrier, who stamped his paws and whistled at the back of his throat if he felt the gap between crisps had become too long.

‘Pint, is it?’ he said, and Brian nodded.

He eased from the stool. ‘Another warm one,’ he said, and Brian nodded again.

Brian handed his money over. There were too many coins. He lifted his pint and beer slipped from the top of the glass and on to the counter.

‘Still looking for work?’ Clive took a cloth and ran it across the wood.

Brian murmured something into his glass and looked away.

‘Tell me about it, love. If they cut my hours any more, I’ll have to go back on the game.’ He turned his hand and examined his nails.

Brian stared at him over the top of his glass.

‘It’s a bloody joke,’ said Clive, and he laughed, and Brian tried to laugh with him, but he couldn’t quite get there.

*

He was on his second pint when they arrived. Harold walked in first, all shorts and shouting.

‘Evening, evening,’ he said, even though the bar was still empty. The men in the corner nodded and looked away.

‘Clive!’ Harold said, as though Clive was the last person he expected to see. They shook each other’s hand and put their other hands over the top of the shake, until there was a pile of shaking and commotion.

Brian watched them.

‘Double Diamond?’ Harold nodded at Brian’s glass.

Brian said no, he’d buy his own, thanks, and Harold said suit yourself, and he turned back to Clive and smiled, as though there was a whole other conversation going on that Brian couldn’t hear. In the middle of the unheard conversation, Eric Lamb arrived with Sheila Dakin, and Clive had to disappear into the back to find a cherry for Sheila’s Babycham.

By the time Brian followed them to the table, he found himself wedged against the wall, trapped between the cigarette machine and the mystery of Sheila Dakin’s bosom.

She wrinkled her nose at him. ‘Have you started smoking again, Brian? You smell like an old ashtray.’

‘It’s my mam,’ he said.

‘Maybe think about getting your hair cut as well,’ she said, and dipped her cherry in the Babycham. ‘It looks a right bloody mess.’

There was a radio on somewhere, and Brian could hear a slur of music, but he couldn’t tell what it was. The Drifters, maybe, or The Platters. He wanted to ask Clive to turn it up, but Clive had been standing at the end of the bar for the last five minutes, twisting a tea towel into the same pint glass and trying to listen to their conversation. It was the last thing he’d want to do.

‘Order, order.’ Harold said and tapped the edge of a beer mat on the table, even though no one was speaking. ‘I’ve called this meeting because of recent events.’

Brian realized he was nearly at the end of his pint. He swilled the glass around to try and catch the foam which patterned the sides.

‘Recent events?’ Sheila twisted at her earring. It was heavy and bronze, and Brian thought it looked like something you might find on a totem pole. It dragged the flesh towards her jaw, and pulled the hole in her ear into a jagged line.

‘This business with Margaret Creasy.’ Harold still held the beer mat between his fingers. ‘John has it in his head it’s something to do with number eleven. Got himself in a right state after church last weekend.’

‘Did he?’ said Sheila. ‘I wasn’t there.’

Harold looked at her. ‘No,’ he said, ‘I don’t expect you were.’

‘Cheeky sod.’ She began twisting at the other earring. Her laugh took up the whole table.

Harold leaned forward, even though there wasn’t any space to lean into.

‘We just all need to be clear,’ he said, ‘about what happened.’

The music had finished. Brian could hear Clive’s tea towel squeak against the glass and the hum of the old men shuffling their words.

‘You might as well sit down, Clive, as stand over there.’ Eric Lamb nodded at the empty stool with his glass. ‘You’re as much a part of this as any of us.’

Clive took a step back and pulled the tea towel into his chest, and said he didn’t really think it was his place, but Brian saw Harold persuade him over with his eyes, and Clive dragged the stool across the lino and pulled himself between Harold and Sheila.

‘I deliberately didn’t ask John tonight.’ Harold sat back and folded his arms. ‘We don’t need another scene.’

‘What makes him think it’s anything to do with number eleven?’ Sheila had finished her Babycham, and was turning the stem of the glass between her fingers. It crept towards the edge of the table.

‘You know John. He’s always looking for something to worry about,’ said Harold, ‘he can’t keep his mind still.’

Brian agreed, although he would never say so. When they were kids, John used to count buses. He reckoned they were lucky.

The more buses we see the better, he said, it stops bad things happening. It would make them late for school, walking round the long way, trying to spot as many as they could. Brian would say, It’s made us late, how can that be lucky and laugh, but John would just gnaw at the skin around his fingers and say that they can’t have seen enough.

‘John doesn’t think that pervert’s done her in, does he?’ said Sheila. The glass tipped towards the floor, and Eric guided her hand back.

‘Oh no. Nothing like that, no. No.’ Harold said no too many times, they came out of his mouth like a string of bunting. He looked down at the beer mat.

‘Wouldn’t surprise me if he has,’ said Sheila, ‘I still reckon he took that babbie.’

Harold looked at her for a moment, and then lowered his eyes.

‘The baby turned up safe, though, Sheila.’ Eric took the glass from her hand. ‘That’s all that matters.’

‘Bloody pervert,’ she said. ‘I don’t care what the police said. It’s a normal avenue, full of normal people. He doesn’t belong there.’

A silence unfolded across the table. Brian could hear the Guinness slide down Eric Lamb’s throat, and the tea towel crease and pleat between Clive’s fingers. He could hear the twist of Sheila’s earring, and the tap of Harold’s beer mat on the wood, and he heard pockets of his own breath escaping his mouth. The silence became a sound all of its own. It pushed against his ears until he could stand it no longer.

‘Margaret Creasy talked to my mam a lot,’ he said. He put the pint glass to his mouth. It was almost empty.

‘About what?’ said Harold. ‘Number eleven?’

Brian shrugged behind the glass. ‘I never sat with them,’ he said. ‘They played Gin Rummy for hours in the backroom. Good company, my mam said she was. A good listener.’

‘She was always in and out of your house, Harold.’ Sheila clicked open her purse and put a pound note in front of Clive.

‘She was? I never saw her.’

‘Probably keeping Dorothy company,’ she said, ‘while you were out and about.’

Brian went to put a tower of coins on the note, but Sheila brushed him away.

‘Dorothy saw Margaret Creasy going into number eleven,’ said Harold. ‘She’s just as hysterical about it as John is. She thinks someone’s said something.’

Clive pulled the empty glasses together, catching each one with a finger. ‘What is there to say? The police said the fire was an accident.’

‘You know Dorothy,’ said Harold, ‘she’ll tell anybody anything, she doesn’t know what she’s saying half of the time.’

The glasses rattled as they left the table.