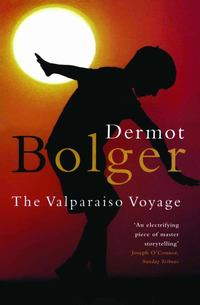

The Valparaiso Voyage

The glass doors opened in the hospital foyer. An ambulance, with its siren turned off and blue light flashing, had pulled up outside. The porter disappeared through a doorway while staff bustled about, allowing me to slip away unnoticed. The beggar was gone. I crossed Dorset Street – a blocked artery of Dublin which had always refused to become civilized. Shuttered charity shops and gaudy take-aways. Pubs on every corner, alleys leading down to ugly blocks of flats. People walked quickly here, trying to look like they knew where they’re going.

Where was I heading, with just two bags waiting for me in a luggage locker at the bus station? But what other sort of homecoming had I any right to expect? I was putting more than just myself at risk by being here, but even without my father’s murder I always knew that one day I would push the self-destruct button by turning up again.

I crossed into Hardwick Street and passed an old Protestant church that seemed to have become a dance club. Across the road a tall black girl stood at a phone box, smoking as she spoke into the receiver. I don’t think she saw the two Dublin girls emerge through an archway from the flats, with a stunted hybrid of a fighting dog straining on his lead. At first I thought they were asking her for a light, until I saw the black girl’s hair being jerked back. She screamed. I stopped. There was nobody else on the wide bend of footpath. Music blared from a pub on the corner. Two lads came out from the flats as well, as the black girl tried to run. The Dublin girls held her by the hair as the youths strolled up.

‘Nigger! Why don’t you fuck off back home, you sponging nigger!’

There were four of them, with the dog terrifying their victim even further. One youth grabbed her purse, scattering its contents onto the ground – keys, some sort of card, scraps of paper and a few loose coins which they ignored. They weren’t even interested in robbing her. I knew the rules of city life and how to melt away. But something – perhaps the look in the black girl’s eyes, which brought back another woman’s terror on a distant night in this city – made me snap. I found myself running without any plan about what to do next, shouldering into the first youth to knock him off balance.

I grabbed the second youth around the neck in a headlock, twisting his arm behind his back. The girls let go their victim in surprise, while the dog circled and barked, too inbred and stupid to know who to bite. The black girl leaned down, trying to collect her belongings from the ground.

‘Don’t be stupid, just run, for God’s sake, run!’

‘Don’t call me stupid!’ she screamed at me, like I was her attacker. One girl swung a hand at her, nails outspread as if to claw at her eyes. The black girl caught the arm in mid-flight, sinking her teeth into the wrist. The first youth had risen to leap onto my back, raining blows at my face as I fell forward, crushing the youth I was still holding. I heard his arm snap as he toppled to the ground. He screamed as the first youth cursed.

‘You nigger-loving bastard! You cunt!’

My forehead was grazed where it hit the pavement, with my glasses sliding off. Their aggression was purely focused on me now, although the second youth was in too much pain to do much. I heard running footsteps and knew that I was for it. But when the thud of a boot came it landed inches above my head. The youth on top of me groaned and rolled off. I heard him pick himself up and run away. The other youth broke free, limping off with the shrieking girls following.

Only now did the dog realize that he was meant to attack us. I sensed him come for me and raised my arms over my face. His teeth had brushed my jacket when I heard a thump of a steel pole against his flank. He turned to snarl at his attacker as somebody pulled me up. It was a tall black man, around thirty years of age. The black girl knelt beside us, crying, cramming items into her purse. A smaller, stockier black man banged a steel pole along the concrete, holding the dog off. The black girl turned to me.

‘Don’t you call me stupid! Don’t you ever!’

‘Stop it, Ebun,’ the man holding me said. He looked into my face. ‘E ma bínú. Can you walk?’

‘Just give me a second.’

‘We haven’t got a second. More of your sort will be back.’

‘They’re not my sort.’

‘They’re hardly mine.’ He bent down to retrieve my glasses from the ground. ‘You should get out of here. Have you a car?’

‘No.’

‘Where do you live?’

‘Abroad.’

‘Where are you staying then?’

‘I don’t know yet. Somewhere.’

The girl, Ebun, looked over her shoulder towards the windows of the flats. ‘He’s the one who’s stupid,’ she said. ‘He jumped right in.’

With a final snarl the dog loped off back towards the entrance. There was a shout from a stairwell. I knew they wanted to get away from there.

‘He’d better come with us,’ the man told Ebun.

She answered in a language I couldn’t understand. My courage had vanished now that the fight was over, I was unsure if my legs would support me.

‘I know,’ the man replied. ‘But we can’t leave him here.’

The stockier man put the steel pole back inside his coat. Arguing in their own language, they half-led and half-carried me back onto Dorset Street, past a row of rundown shops and around the corner into Gardner Street. Their flat was at the top of a narrow Georgian house, with wooden steps crumbling away and rickety woodwormed banisters. I had once haunted the warrens of bedsits around here, knowing every card school in the anonymity of flatland where one could sit up all night to play poker and smoke dope.

But the journey up the stairs now had a dream-like quality. Every face that appeared on each landing was black or Eastern European. I had spent a decade abroad, but somehow in my mind Ireland had never changed. Maybe they didn’t hang black people in Navan for being the Devil any more, but before I left the occasional black visitor was still a novelty, a chance to show our patronizing tolerance which distinguished us from racist Britain. We had always been an exporter of people, our politicians pleading the special case of illegal Irish immigrants living out subterranean existences in Boston and New York. So, with our new-found prosperity, why did I not expect the boot to be on the other foot? Ebun unlocked a door and they helped me onto a chair in their one-room flat. She put some ice from the tiny fridge into a plastic supermarket bag. Kneeling beside the chair she held it against my forehead.

‘To keep the swelling down,’ she said. ‘You were crazy brave. I should not have shouted at you.’

‘I didn’t mean to call you names. I just wanted to make you run.’

‘I don’t run,’ she said. ‘No more running. I see too much to run any more.’

The men talked in low voices in their own language. Another man joined them, staring at me with open curiosity. I tried to stand up, wanting to escape back down onto the street. These damp walls reminded me too much of things I had spent a lifetime fleeing. I wondered at what time the bus station closed.

‘Where are you going?’ Ebun pushed me back. ‘You have been hit. You must rest.’ She adjusted the ice-pack slightly.

‘He saw everything,’ the stocky man said. ‘I know those kids. This time we have a witness. I say we call the police.’

‘No,’ I said quickly. ‘I can’t.’

‘Can’t what? Go against your own kind?’

‘It’s not that.’

‘Leave him alone,’ Ebun said. ‘What’s the use of a court case in six months’ time? By then we could have all been put on a plane back to Nigeria. Besides, a policeman anywhere is still a policeman. We should never trust them.’

‘We thank you for your help,’ the man who had picked me up said. ‘This should not have happened. I tell my sister not to go out alone, but do you think she listens? Have you eaten?’

‘No.’

‘We have something. It is hot.’

I had smelt the spices when I entered the flat. The stocky man went to the cooker and ladled something into a soup dish. ‘E gba,’ he said, handing me what looked like a sort of oily soup. ‘It is called egusi. My name is Niyi.’ He smiled but I knew he was uneasy with my presence. Ebun removed the ice-pack and they talked among themselves as I ate. Finally her brother approached.

‘Tonight you have nowhere to stay?’

‘Nowhere arranged as yet.’

‘Then we have a mattress. You are welcome.’

I had enough money for a hotel. I was about to say this when I looked at Ebun’s face and the still half-antagonistic Niyi. Strangers adrift in a strange land, refugees who had left everything behind, who lived by queuing, never knowing when news would come of their asylum application being turned down. This flat was all they possessed.

‘I would be grateful,’ I replied.

‘Lekan ni oruko mi. My name is Lekan.’ He held his hand out. I shook it.

‘My name is Cormac,’ I lied, with the ease of ten years’ practice.

Lekan led me across the landing to a small bathroom. The seat was broken on the toilet, which had an ancient cistern and long chain. I washed my face, gazing in the mirror at my slightly grazed forehead. Then I peered out of the small window: rooftops with broken slates, blocks of flats in the distance, old church spires dwarfed by an army of building cranes, the achingly familiar sounds of this hurtful city.

A few streets away the woman I had been taught to call ‘Mother’ lay dying in hospital. Out in the suburbs beyond these old streets the woman I had once called ‘wife’ lived with the boy who once called me ‘Father’. Conor’s seventeenth birthday was in two months’ time, yet he lived on in my mind the way he had looked when he was seven.

On the landing the Nigerians were bargaining in a language I could not understand and then in English as they borrowed blankets to make up a spare bed. My forehead hurt. Everywhere my eyes strayed across the rooftops brought memories of pain, so why was my body swamped by the bittersweet elation of having come home?

II SUNDAY

Asofa with scratched wooden arms that probably even looked cheap when purchased in the 1970s; a purple flower-patterned carpet; one battered armchair; a Formica table that belonged in some 1960s fish and chip shop; an ancient windowpane with its paint and putty almost fully peeled away. I woke up on Sunday morning in Ebun’s flat and felt more at home than I had done for years.

A solitary shaft of dusty light squeezed between a gap in the two blankets tacked across the window as makeshift curtains. It fell on Niyi’s bare feet as he sat on the floor against the far wall watching me. He nodded, his gaze not unfriendly but territorial in the way of a male wary of predators in the presence of his woman.

I looked around. One sleeping-bag was already rolled up against the wall. Ebun occupied the double bed, her hair spilling out from the blankets as she slept on, curled in a ball. Niyi followed my gaze. Maybe he had just left the double bed or perhaps the empty sleeping-bag was his. I’d no idea of where anyone had slept. All three Nigerians had still been talking softly when I fell asleep last night.

‘Lekan?’ I enquired in a whisper.

‘Gone. To help man prepare for his appeal interview, then to queue.’

‘What queue?’

‘Refugee Application Centre. He needs our rent form signed.’

‘But it’s Sunday?’

‘On Friday staff refuse to open doors. They say they frightened by too many of us outside. Scared of diseases I never hear of. By Monday morning queue will be too long. Best to start queue on Sunday afternoon, and hope that when your night-clubs finish there is less trouble with drunks. Lekan does not like trouble.’

‘How will he eat?’

Niyi shrugged. ‘We bring him food. Lekan is good queuer. I only get angry. Too cold. Already I am sick of your country.’

He pulled a blanket tighter around him. We had been whispering so as not to wake the girl. It was seven-twenty on my watch. There would be nowhere open at this time in Dublin, not even a café for breakfast. I turned over. My pillow was comfortable, the rough blanket warm. My limbs were only slightly stiff from the thin mattress. I could go back asleep if I wished to. From an early age I had trained myself to fall asleep anywhere.

Not that this ability was easily learned. I spent five years sleeping in the outhouse as a child, yet the first few nights, when I barely slept at all, remain most vivid in my mind. My terror at being alone and the growing sensation of how worthless and dirty I was. Throughout the first night I was too afraid to sleep. I knelt up on the desk to watch lights go out in every back bedroom along the street. My father’s light was among the first. Yet several times during the night I thought I glimpsed a blurred outline against the hammered glass of the bathroom window. I didn’t know whether it was my father or a ghost. But someone seemed to flit about, watching over me or watching that I didn’t escape.

I’d never known how loud the darkness could be. Apple trees creaking in Hanlon’s garden, a rustling among Casey’s gooseberry bushes. Paws suddenly landing on the outhouse roof. Footsteps – real or imagined – stopping halfway down the lane. Every ghost story I had ever heard became real in that darkness. Dawn eventually lit the sky like a fantastically slow firework, and, secure in its light, I must have blacked into sleep because I woke suddenly, huddled on the floor with my neck stiff. My father filled the doorway.

‘School starts soon. You’d better come in and wash.’

He didn’t have to tell me not to mention my night in the outhouse at school. Instinctively I understood shame. Cormac sat at the kitchen table. He didn’t seem pleased at his victory, he looked scared. Phyllis refused to glance at me. She placed a bowl of porridge on the table, which I ate greedily, barely caring if it scalded my throat.

‘Comb his hair,’ my father instructed her. ‘He can’t go looking like he slept in a haystack.’

But the tufts would not sit down, no matter how hard Phyllis yanked at them. Finally she pushed my head under the tap, then combed the drenched hair back into shape. Her fingers trembled, her eyes avoiding mine. She snapped at Cormac to hurry up, pushing us both out the door. We were late, trotting in silence at her heels. Lisa Hanlon stared at me as she passed with her mother. Phyllis took my hand, squeezing my fingers so tightly that they hurt. Every passer-by seemed to be gazing at me and whispering.

‘You mind your brother this time.’ Her hiss was sharp as she joined our hands together, pushing us through the gate. We walked awkwardly towards the lines of boys starting to be marched in.

I glanced at Cormac whose eyes were round with tears. ‘If you slept in my bed I’ll kill you, you little gick,’ I whispered. He released his hand from mine once Phyllis was out of sight.

It was hard to stay awake. My eyes hurt when I rubbed them. I avoided Cormac at small break, while a boy jeered at me in the long concrete shelter: ‘What was your mother screaming about yesterday?’

‘She’s not my mother.’

Cormac moved alone through the hordes of boys, being pushed by some who stumbled into his path. But he seemed content and almost oblivious to them, absorbed in some imaginary world. I watched him walk, his red hair, his skin so white. He was the only boy I knew who washed his hands at the leaky tap after pissing in the shed which served as a school toilet. At that moment I wanted him as my prisoner too, himself and Lisa Hanlon with tied hands forced to do my bidding on some secret island on a lake in the Boyne. I don’t know what I really wanted or felt, just that the thought provided a thrill of power, allowing me to escape in my mind from my growing sense of worthlessness.

When lunchtime came I knew Cormac was about to get hurt. Bombs were exploding in the North of Ireland, with internment and riots and barbed wire across roads. I didn’t understand the news footage that my father was watching so intently at night. But Pete Clancy’s gang had started to jeer at Cormac, chanting ‘Look out, here comes a Brit’ and talking as though the British army was a private militia for which he was personally responsible.

Yet I had never heard him mention his father or living in Scotland. It was like he had no previous existence before gatecrashing my life in Navan. He spoke with a softer version of his mother’s inner-city Dublin accent, but this made no difference to Pete Clancy, who detested Dubliners anyway. Cormac was the nearest available scapegoat and therefore had to suffer the consequences.

I watched from the shed as a circle of older boys closed in on him, while younger lads ran to warn me that he was in trouble. The prospect of violence spread like an electric current through the yard. I wanted Cormac hurt, yet something about his lost manner made me snap. The huddle of boys seemed impenetrable as they scrambled for a look. They let me through as if sensing I meant business. But even if I could have helped him I had left it too late. Cormac’s shirt was torn, his nose a mass of blood. Pete Clancy stopped, knowing he had gone too far. Behind him Slick McGuirk and P. J. Egan stood like shadows, suddenly scared. Slick was trembling, unable to take his eyes off Cormac, maybe because when they had nobody else to torment the two companions always tormented him. Pete Clancy let go of Cormac’s hair and all three stepped back, leaving him kneeling there.

The circle was dispersing, voices suddenly quiet. I knew Mr Kenny was standing behind me, the tongue of a brass bell held in his left fist and his right hand clenching a leather strap with coins stitched into it. He looked directly at Pete Clancy. ‘What’s been going on here?’

‘Two brothers, a Mháistir, they were fighting.’

Clancy’s eyes warned me about what could happen afterwards if I contradicted him. McGuirk and Egan took his lead, staring intimidatingly at me.

‘Did you try to stop them, Clancy?’

‘I tried, a Mháistir.’

The Low Babies and High Babies were sharing a single classroom that year, while the leaky prefab, which previously housed two classrooms, was being demolished to make room for a new extension. Every boy knew that the school would never have leapfrogged the queue for grant aid if Barney Clancy hadn’t pulled serious strings within the Department of Education. My father might be respected but my word held no currency against a TD’s son. I looked at Pete Clancy’s closed fist which still held a thread of Cormac’s hair.

‘Is this true, Brogan?’ Mr Kenny asked me.

‘No, sir. He’s not my brother.’

Someone sniggered, then went silent at the thud of Mr Kenny’s leather against my thigh. The stitched coins left a series of impressions along my reddened flesh.

‘Don’t come the comedian with me, Brogan!’

It was hard to believe that two hundred boys could be this quiet, their breath held as they anticipated violence being done to somebody else. Pete Clancy eyed me coldly.

‘Did you strike this boy?’ Mr Kenny asked me again.

Cormac looked up from where he knelt, trying to wipe blood from his nose. ‘No, he didn’t.’

‘I did so!’ I contradicted him, not knowing if I was trying to save Cormac or myself or us both. Clancy’s henchmen haunted every lane in Navan, whereas with Kenny it would simply be one beating. ‘He’s a little Brit,’ I said, parroting Clancy’s phrases. ‘They’re only scum over there in Scumland.’

‘Brendan didn’t touch me, sir,’ Cormac protested. ‘Please leave him alone.’

‘Stand up,’ Kenny told him. Cormac rose. I knew he was crazy, only making things worse. But Clancy and the others stepped back, suddenly anxious. Cormac’s honesty was illogical. There was no place for it in that schoolyard and they were suddenly scared of him as if confronted by somebody deformed or spastic.

‘You needn’t be afraid of what he’ll do to you at home. I’ll make sure your mother knows about this,’ Mr Kenny said, beckoning us to follow him.

A large wooden crucifix dominated the corridor outside the head brother’s office, framed by a proclamation of the Republic and a photo of a visiting bishop at confirmation time. I stood outside the office while Slick McGuirk and P. J. Egan pressed their faces against the window on their way home, muttering, ‘You’re dead, fecking dead!’

Their threats weren’t directed at Cormac sitting on a chair near the statue of Saint Martin de Pours, but at me. They ignored the child who had defied them, but, in acquiescing, I had become their new bait.

Phyllis didn’t even glance at me when she emerged from the head brother’s office. Her silence lasted all the way home as she gripped Cormac’s hand and I fell back, one step, two step, three steps behind them. Conscious of watching eyes and sniggers. Aware of hunger and of how my palms stung so badly that I could hardly unclench my knuckles after my caning by the head brother. Cormac didn’t speak either. Perhaps he realized that the truth was of no use or maybe he was exacting revenge for every sly pinch I’d ever given him.

The grass needed a final autumn cut in the back garden. I remember that leaves had blown in from the lane to cover the small lawn with a riot of colour. They looked like the sails of boats on a crowded river. I wanted nothing more than to block the real world out by kneeling to open my bruised hands and play with them.

‘Tháinig long ó Valparaiso, Scaoileadh téad a seol sa chuan…’

I remembered Brother Ambrose’s voice in class a few weeks before, losing its usual gruffness and becoming surprisingly soft as he seduced us with a poem in Irish about a local man who sees a ship from Valparaiso letting down its anchor in a Galway bay and longs in vain to leave his ordinary life behind by sailing away on it to the distant port it had come from.

Phyllis had left us alone in the garden. I knelt to gather up a crinkled fleet of russet and brown leaves and cast them adrift. Cormac watched behind me, then knelt to help by sorting out more leaves and pushing them into my hands.

‘What are they?’ he asked.

‘A fleet of ships. Sailing across the world to Valparaiso.’

‘Where’s that?’

‘Somewhere that’s not here.’

He nodded companionably as if the confrontation in the schoolyard had finally given us something in common. It was the first time we became absorbed in playing together, our hands sorting out the leaves excitedly.

‘The purple ones can be pirates,’ he suggested, ‘slaughtering the goody-goody ones that are brown.’

‘Did you come from Scotland on a ship?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘What was it like, Scotland?’

‘I don’t know.’

Footsteps made us turn. Phyllis was struggling with a spare mattress she had taken down from the attic, trying to force it out the kitchen door. Mutely we watched her haul it down the path. My blankets were already in the outhouse from last night. I have a memory of Cormac and I holding hands as we stood together. But this couldn’t be possible, because when she ordered me into the outhouse I was still clutching a pile of leaves tightly in both fists.

‘Put those down before you litter the place,’ she said. ‘Make a bed for yourself. I’ll not have a thug under the same roof as my son.’

Her make-up was streaked from tears. I didn’t want to simply drop the leaves. Cormac opened his hands and I passed them to him so that he could continue the game. He was still holding them, solemn-faced, when Phyllis slammed the door.

I don’t know at what hour my father came home, but it was long after the chorus of wood saws and the tic-tic-tic of upholstery tacks had died out in the garden sheds. He brought down a tray with water and a bowl of lukewarm stew. I told him the truth about Pete Clancy, crying my eyes out, desperate for someone to believe me. The terrible thing is that I think he did believe me, but just couldn’t afford to admit it to me or to himself.

Barney Clancy had dominated that outhouse on every occasion he stood there. His rich cigar smoke, the shiny braces, the shirts he was rumoured to have specially made in Paris. After years of hard times Clancy was putting Navan on the map. Without him there would be no Tara mines or queue-skipping for telephones or factories set up to keep the 1950s IRA men out of mischief. The new wing for Our Lady’s Hospital would not have been built, nor the Classical School resurrected from the slum of Saint Finian’s, and the promise of a municipal swimming pool would have remained just a promise.