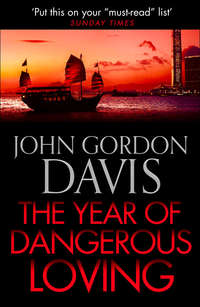

The Year of Dangerous Loving

‘A Miss Romalova for you, sir,’ said Miss Ho.

‘Put her through! Olga! Are you all right?’

She chuckled. ‘I am very well, except for my poor pussy. And my heart, my heart is very sore also.’ Hargreave was blushing. ‘Will my heart get better on Friday?’

‘Yes.’ Oh yes, he could not wait for Friday. ‘So your work-permit is okay?’

‘Yes, the police have extended for three months. And the big boss has agreed also.’

Oh, yes. ‘Well, I’ll be there on the seven o’clock ferry.’

‘Lovely! Which hotel do you want to stay in?’

‘The Bella Mar.’

‘So expensive. Why not another hotel, not so much?’

‘No, the Bella Mar.’ He had to have her in one of those airy, exotic suites, beauty like hers deserved the Bella Mar.

‘Shall I reserve? Maybe if I reserve I can get a small commission.’

‘Fine.’ Hargreave grinned.

‘I will give it back to you.’

‘No, you keep it,’ he laughed.

She seemed to accept that as reasonable. ‘I cannot meet you at the ferry, darling, because I must be at the club. But do not come there because then you must pay entrance, and the drinks are so expensive. Telephone me there when you are ready, and I will come to the hotel. But you will have to pay the bar-levy, I’m sorry.’

‘That’s all right.’ Talk of money made him uncomfortable.

‘But I will give you a discount for me, darling, don’t worry. And we will have a lovely weekend, I promise.’

Hargreave grinned, blushing: ‘And I promise you.’ He wanted to tell her about his health-kick but he felt silly.

‘Oh darling, I am so excited. I thought about you all last night at the club.’

Hargreave didn’t want to hear about the club. ‘I thought about you too.’

‘Did you really? I am very pleased. Okay, I must go to sleep now, I have to work tonight.’

Work. He did not want to think about it.

After he hung up he slumped back in the chair, and tried to make himself think about it. Lord, what am I doing, feeling like this about a …? Say it – a whore? Feeling possessive … romantic … smitten. Feeling … over the moon about her. Aren’t you making a bit of a fool of yourself? Don’t forget she’s a whore.

But I wouldn’t be the first man to get smitten by a whore. Whores can be fascinating. Exotic, romantic, even, you wouldn’t be the first man to fall in love with a whore.

Fall in love? What are you talking about, man? You’re not in love, you’re just in lust You’ve had a bit of a tough time with Liz, unloved, sex-starved, so it just feels like love, you just feel sorry for yourself. Whores are for fun, not love …

Okay, so have fun. Enjoy it, stop analysing it. Stop thinking about her ‘work’, and her ‘customers’, stop flinching about ‘discount’ and be grateful for it, grab every discount she gives you because this fun is going to cost you plenty if you keep it up. A three-month extension on her visa? How can you keep up with this for three months? And you won’t want to, you’ll burn the whole thing out soon and she’ll go back to Russia and you’ll be relieved. So be cavalier, just enjoy …

But cavaliers were fit, cavaliers could keep up with their lovers, they did not fall by the wayside just because they were forty-six. He felt tired when he got home from chambers, and he wanted a stiff whisky, but he made himself go out to jog again. But he only managed two kilometres before his heart and his knees told him to stop: the image of her nakedness could not beat the ache in his legs today. So, you gave yourself a workout at lunchtime, don’t overdo it. He walked back to his apartment block on Mansfield Road. He had one beer, one whisky, two boiled eggs, and went to bed. He was asleep before eight o’clock.

The next morning he could hardly stand. His knees were not swollen but they were giving him agony.

‘Cartilage inflammation,’ Ian Bradshaw said cheerfully on Wednesday. ‘From jogging – told you not to do it. Buy a bicycle, I said. Or an exercycle, one of those stationary things that executives use. And buy yourself a pair of proper running shoes – but don’t run, go for walks. Get the best, with springy soles. And for the next week that’s all you can wear on your feet.’

‘But I can’t wear running shoes to chambers.’

‘You’re the boss, aren’t you? Get a black pair, to go with your pinstripe suit, I’ll give you a medical certificate saying you’re a stretcher-case without them. Wear them to court, to cocktail parties, or you’ll have a cartilage removal operation – want that?’

‘No,’ Hargreave said sincerely.

‘Otherwise you’re in good shape,’ Ian said. ‘Heart fine. Got some colour again. Let’s look at my scar?’

Hargreave peeled back his shirt. Ian peered.

‘You’re healthy. Getting older, that’s all. I did a good job on that bullet, what’s left is pretty sexy. Tell the girls it was a jealous husband, makes them feel protective.’ He sat back. ‘What news of Liz?’

Hargreave pulled his shirt back on. ‘We’re getting divorced.’

Ian nodded. ‘Still in San Francisco?’

Hargreave buttoned his shirt. ‘I think so.’

‘No truth in the rumour she’s coming back to town?’

Jesus. ‘Who told you that?’

‘Yacht club. Don’t know the source.’

Hargreave’s heart sank. Just when he was going to have some fun. ‘I’ve just received her lawyer’s letter. If she’s coming back it’s just to pack the rest of her things.’

‘You can come and stay in my guest room while she does,’ Ian offered. ‘You don’t want any more scars. Did you marry under Californian law?’

‘Yes.’

Ian shook his head. ‘Same with me and Janet. Community of Property, half of everything you own. If Janet divorced me I’d be in trouble. Okay!’ He slapped Hargreave’s arm and stood up. ‘Just remember you’re forty-something, not thirty-something, come back for another vitamin B jab next week, and eat your wheaties. And whoever-she-is should have a smile all over her face. But no jogging. Buy an exercycle if you don’t want a bicycle.’

6

He ended up buying both. He went to Lane Crawfords for the super sports shoes – they didn’t have his size in black, he had to take a white pair – then he went to buy an exercycle. There were all kinds. Hargreave went for the most expensive model, with various speedometers and clocks and mileometers and calorie-counters. State-of-the-art. Made in America. And expensive, compared to similar machines made in China, Korea, Hong Kong, Japan. ‘But much better everything.’ Hargreave wanted much better everything. For Olga? No – for himself. About time he spent some money on himself. He arranged to have it delivered to his apartment, and he was about to go back to his chambers when he spied the mountain bicycles.

They were impressive. So gleaming – all the colours of the rainbow, all the gear, all the variations. Hargreave spent another hour with the salesman, asking searching questions. ‘What about knee-impact?’ He ended up buying the latest Canadian lite-weight fibre-glass super 36-Shimano-gears job, a machine which, judging by the salesman’s account, would take him over the Himalayas with ease. Nothing but the best for Hargreave! Then he had to buy the latest in crash helmets, metallic red – he fancied blue but they didn’t have any. Then gloves. Then a rainproof tracksuit. And goggles. And two sweatbands – ‘You must have two, sir …’

Hargreave arranged for the whole purchase to be delivered to his apartment and walked stiffly back through the crowds to his chambers. He was pleased he had grasped the nettle of his ageing body, which no lesser savant than Ian Bradshaw had said was not too bad, which Olga evidently thought was pretty damn good. And she would know …

His own wit made him grin widely.

‘Enjoy,’ he said to himself. ‘Just enjoy …’

But it was hard work to enjoy.

His exercycle and bicycle were resplendent in the middle of his living room when he arrived home, his red helmet and other gear draped on the sofa. (Ah Moi, his amah, was both mystified and amused.) Hargreave decided not to ride his new bicycle today: he was stiff all over, it was hot outside, the rush-hour was still on, all good reasons for the Great Indoors. With determination he got into his tennis shorts, pulled on his new sports shoes, switched on his television, mounted his new exercycle, checked that all his dials were on zero, and began to pedal.

He pedalled hard, staring at the television; within moments he was exhausted. He stopped. He looked at the mileometer: some four hundred yards. He looked at the clock: thirty-two seconds. He looked at the calorie-counter – not a sausage. And so boring.

Well, so these things take time – he had found the exercycle at the gymnasium hard work too. Maybe he should start with the mountain bike.

Hargreave put on his flash red helmet and descended in the elevator with his flash new Canadian Super-lite, Shimano-36-gear, hot-and-cold-running-water mountain bike. He mounted it, and set off. ‘Into the Unknown …’

And, Lord, it was the unknown. It was thirty years since Hargreave had ridden a bicycle; he had forgotten what hard work is required of the legs. The area immediately surrounding his apartment complex was flat, but within two circuits his legs were aching. He came to the exit and stopped for a little rest. From here he had the choice of three directions: the steep, winding road up towards the Peak, or a more gentle incline around the Peak, or the road that led downhill towards Central. Rush-hour traffic was using all three roads. Hargreave got the ache out of his legs and chose the road that inclined gently around the side of the Peak. He adjusted his helmet, selected second gear, waited for a gap in the traffic; and went for it. He pedalled flat out across the road, then swung right, uphill.

He pedalled furiously as traffic overtook him. The ache came crashing back into his legs, his heart started pounding. He pedalled and pedalled, feeling nervous now midst the sweeping traffic roaring up from behind. He pedalled and pedalled, standing now, toiling, teeth clenched, desperately trying to keep to the extreme left of the road, out of harm’s way. He pedalled and pedalled, trying to think of Olga to obliterate the pain; then he just had to stop. He wobbled to a halt beside the kerb.

He was exhausted: his whole body was trembling, his legs crying out; even his arms ached. His head was hot in the helmet, and he took it off. A legal friend passing in his Jaguar recognized him and shouted ‘Go, Al, go!’ Hargreave managed a sheepish wave. So now he was self-conscious as well as exhausted. If they knew why he was doing this, for a twenty-three-year-old Russian whore, they would kill themselves with laughter. He looked backwards. Maybe he had done threequarters of a mile.

But a Hargreave does not give up easily. When the pain in his legs subsided he took a deep breath and toiled on.

But toiled. This gentle incline was not gentle at all. And it went on and on. He knew the road well, he thought he could visualize the turns and gradients ahead, but it all looked very different from here. He tried to put the machine into a lower gear, shoving the levers like the salesman had shown him – which made the handlebars wobble dangerously. A passing car hooted at him, swerving. Desperately he pushed both levers simultaneously and the gears crunched and jerked and then spun, in no gear at all – suddenly Hargreave’s legs were whirling, he wobbled, his front wheel hit the kerb, and he crashed.

Fortunately he was going very slowly. Hargreave only toppled off his bicycle. But he landed with a nasty thump, on his side. A passing motorist hooted and laughed. Hargreave clambered up, embarrassed.

‘Oh Lord …’

When the ache subsided in his legs, he examined the gear mechanism, cussing.

He did not understand what he was looking at, though it had seemed intelligible in the shop: there were layers of cogs on both the pedal contraption and the rear wheel: the selection of which particular cogs the chain operated at any given moment was determined by the little levers on the handlebars. Right; understood. But now the chain hung lifelessly. Hargreave gingerly lifted it with forefinger and thumb and tried to put it back on the cogs. Any cogs. The chain refused to oblige. In exasperation he wrenched, and finally the chain reluctantly took its place. Wearily Hargreave remounted, shoved off and trod on the pedals.

And fuck me if the infernal machine was not now in top gear. He wobbled to a halt again, another motorist blaring at him. ‘Oh fuck off!’ Hargreave muttered. He retreated to the kerb and glared down at the cogs.

‘Okay, that’s it!’ Hargreave said – he simply did not understand the gears. He wasn’t going to fuck about with the fucking chain again. So there was nothing for it but to return home – mercifully downhill – and get one of those kids in the apartment block to explain the gears to him. Grateful that his ordeal was almost over, he awaited another gap in the traffic, then wheeled his bicycle across the road. He reached the other side with doubtful safety, took a deep breath, faced his machine downhill, and mounted.

Alistair Hargreave, Director of Public Prosecutions, was about a mile uphill of the entrance of his apartment complex when he set off. Downhill, in top gear. He wearily trod on the pedals, once, twice, and the machine leaped forward like an enthusiastic pony. And off he sped.

And this was more like it! This was what he imagined when the salesman had eulogized about the Shimano 36-speed gears, making it sound as if he would whiz gracefully everywhere. Hargreave went swooping down the hill effortlessly, cool wind suddenly on his sweating face, the sunset caressing instead of beating him – this was almost like sailing! There was no other downhill traffic and he had half the swathe of road to himself. He trod on the pedals harder, and the machine surged again, going faster, and faster, the uphill traffic flashing by now. Hargreave pedalled joyously, effortlessly, gracefully, the wind whistling in his ears, drying his sweating face; harder he pedalled, and harder. And, oh, he would love to just keep going down this steep winding peak all the way down to Central, fun fun fun all the way. That’s what he’d do tomorrow, by God – ride down to the Supreme Court and then take the Peak tram home with his bike and then it was downhill once more from the top of the Peak to his apartment.

That is how Hargreave was feeling on his new Canadian mountain bike as he approached the entrance to his apartment complex. Halfway down the hill his speedometer told him he was doing thirty miles an hour, threequarters the way down he was doing thirty-five. When he was a hundred yards from the entrance he was doing an exhilarating forty, and he felt twenty-three years old, like Olga. When he was fifty yards from the entrance, Hargreave began to apply his brakes for the turn.

First he applied the rear, and the machine slowed somewhat, screeching. Twenty yards from the entrance Hargreave felt he was going too fast to make the turn and he jerked on the front brakes as well and the machine lurched. Ten yards from the entrance Hargreave panicked: he had to make a ninety-degree turn into a blind gateway at terrifying speed. He wrenched on both brakes with all his might and rang his bell frantically. He hurtled towards the entrance. Two yards from it he filled his lungs and bellowed ‘I’m coming!’ and he clenched his teeth and swung the handlebars.

Hargreave swung into the blind entrance at a breakneck fifteen miles an hour, slap-bang into an oncoming car. All he knew was the terrifying wobble of his hurtling turn, his wheels juddering, then the bonnet of the car looming towards him, the skid of its wheels as the driver slammed on the brakes, the blast of his hooter, the radiator roaring towards him, then crash! Hargreave smashed into the car head-on with a blinding jolt, his front wheel buckled and his rear wheel bucked, and he flew through the air. He went sailing over the handlebars, hit the bonnet, skidded along it, and smacked head-first into the windscreen.

The windscreen was fucked. The bike was fucked. ‘And so am I.’

7

That was Wednesday. Hargreave took it very easy on Thursday. He did not go to the gym. He did not ride his exercycle. He did not have a drink. He did not even go to his chambers – he stayed in bed. But he re-read Champion’s uranium file, finally making a note in the Investigation Diary that he recommended the expenditure of further police funds ‘in view of the international importance’. It eased his conscience that he had done some work.

But when Friday dawned he felt wonderful. He still had some stiffness, but he was rested, he had been off the booze for thirty-six hours, his body felt wide-awake: and tonight he was going to Macao! He swung out of bed in the sunrise, to get the day by the tail good and early – and he winced. He had more than some stiffness: the wonderful feeling was only in his head. He walked to the bathroom very experimentally. His knees were still painful and he had a big bruise on his hip. He lowered himself very carefully into a hot bath and lay there, eyes closed, thinking of Olga.

After a moment he felt as excited as a teenager again, his aches and pains did not matter a damn. He knew it was crazy, but that’s how he felt.

It felt even more like that as, in the sunset, the hydrofoil sped across the South China Sea towards Macao. The whole world was exotic, the haze, the mauve islands, the junks, the Pearl River mouth, and he was going to the most exotic girl in the world. He was smiling with anticipation as he swigged his cold San Miguel beer in the first-class cabin, his first drink in forty-eight hours: it was going down into his system like one of Ian Bradshaw’s vitamin B shots. He was impatient with the delays at the immigration counters, but he loved the crowds, the noise, the smell of the place. He had a grin all over his face as his taxi sped and honked and swerved him along the teeming waterfront, then wound up the knoll to the gracious Bella Mar. He strode into the picturesque old hotel, and he loved every creaking floorboard and pillar and potted palm and smiling Chinese. It almost felt as if he had come home. He checked in with a flourish and hurried up to his suite with hardly a hobble. He dumped his bag, snatched a bottle of whisky out of it, poured a big shot, then picked up the telephone and dialled the Heavenly Tranquillity Nite-Club.

‘Hullo, darling!’ Olga cried. ‘Are you really here?’

‘In the flesh. In the hotel. In the bedroom. In the bed.’

‘Oh darling, do not go anywhere!’

Twenty minutes later he heard her running up the staircase. He flung open the door as she burst into it. And there she was, even more beautiful than he remembered, her mass of golden hair piled up on her head, her big blue eyes sparkling, her lovely bosom bursting out of her dress, her wide laughing smile. Hargreave’s heart turned over at the sheer glory of her. ‘Olga …’

He clutched her joyously, felt her fulsome young womanness against him; and he turned her as he kissed her and jostled her towards the bed, laughing into her mouth. She collapsed on to the bed, making giggling noises, and he fell on top of her, one hand wrenching up her dress, the other grappling with his belt. ‘The door –’ He scrambled off her, his trousers halfway down, hobbled painlessly to the door, slammed it and turned back to her. Olga was laughing, her dress up round her waist, her lovely long legs bent as she raised her hips and wrestled her panties down. As Hargreave blundered towards her she hooked them on to her big toe, pulled back the elastic, then let go. They sailed through the air over his head as he collapsed, laughing, on top of her.

They had a wonderful time that weekend. For a week he had fed on the image of her beautiful body, and now he truly had her again. And despite his aches and bruises, his health-kick had paid off: it seemed he wanted to make love to her all the time. And it felt like love. It had almost felt like that last weekend when he left her waving on the jetty. For at least half the week it had still felt like that as he laboured at his exercises; only sometimes had he managed to convince himself that it was only a crazy case of lust. But this glorious weekend he knew that it was not just that, it was better – it was besottedness. He was besotted with her, her tumult of golden hair, her fragrant loins, her magnificent breasts – it seemed he could not get enough of her, there was no feeling more magnificent, more lovely than her body under his, her legs locked around his, thrusting, thrusting into the sweet hot depths of her. Every position she adopted was wildly erotic but the most magnificently important one was to feel her full naked beauty splayed out underneath him.

But there was plenty of laughter, too, and plenty of other fun. She loved jokes. They had the same sense of humour, the same sense of the ridiculous. She thought his health-kick was a hilarious story, and when he came to the bit about writing off his new mountain bike she went into roars of laughter. That established him as a raconteur, and thereafter, whenever he started to tell her a joke she began to giggle, even before he reached the funny part, and when he came to the punchline she threw back her head and guffawed, her lovely eyes wet.

‘The way you tell a story!’

He was a scream, apparently. Hargreave knew he could tell a good tale when he felt like it, when he was in the mood, but it seemed a very long time since he had felt like that; he had forgotten how entertaining he could be. Now he was happy, and it was lovely to be in lust with somebody who laughs a lot and thinks you’re very amusing, it was delightful to laugh at his own jokes again. She was a good story-teller too. She was a natural mimic, her imitation of the English and American accents was very good. She was a born actress, and told a story with her hands and eyes and face and body-language. He was delighted to find out that Russians and English laughed at the same things, that many of his jokes had Russian versions which were often funnier.

‘Darling, Russians tell lots of jokes because they drink so much because that is all there is to do, jokes and drink is all we have to laugh about.’

And it was fascinating, exotic, that she was Russian; from behind that Iron Curtain, suddenly let loose in the big wide world. He wanted to know all about her life in Russia, about her parents, her home, her schooling, her work, her friends. He built up a long series of images of her, hoeing the collective fields in the spring, harvesting in summer, the sweat running off her, her lovely girl-thighs steamy, dust and grit in her flaxen hair, her sexy hands coarsened; he imagined her bleak schoolhouse, hot in summer, cold in winter, smelling of unwashed bodies and chalk and books.

‘I always sat at the very back of the class so I could cheat easier – everybody cheats all the time in Russia, darling, it is the only way to get anything –’

He imagined her swimming with her friends in the muddy river in her underwear.

‘– and sometimes we swam naked, when there were no boys, that was great fun, oh that made us want to be free, to run away from Russia, swim in the lovely blue sea in the sunshine with palm trees on the beach, and Coca-Cola and icecream, and then dance and fuck like crazy, like the Americans do –’

The image of a dozen Russian schoolgirls romping naked in the river was erotic, even if it was muddy. ‘What made you think Americans did that? Did you have access to American books and magazines?’

‘Of course, they were forbidden, but somebody always had some old magazine that had been smuggled, or from the black market, and of course we were taught at school that Americans were terrible people who only thought about eating food that makes them fat, and making money and making war – and that they fuck like crazy. Anyway, we studied the magazines and saw the fashions and the beautiful girls and the beautiful cars and the beautiful food and the white beaches with the palms and the Coca-Colas and the icecream and beef-steak, and the blue sea, and it looked pretty good to us.’