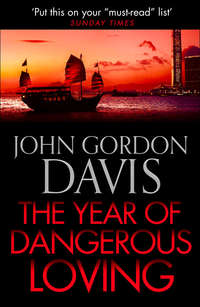

The Year of Dangerous Loving

He grinned: ‘And did you? Fuck like crazy?’ He was not sure he wanted to hear the answer.

She shrugged. ‘That’s all there is to do in Russia, darling. But we were only schoolgirls, we didn’t have much experience yet.’

Her candour was endearing, almost. She was a very honest soul. ‘So how old were you when you first went to bed with a man?’

‘Man, or a boy? I made love to my first boy when I was fourteen. Not too bad, huh? I’d had big breasts for two years. I was driving a tractor. I was having an orgasm, because the tractor seat was vibrating between my legs. This boy saw me and he said, “Come here and I’ll give you a better one”’

‘And he did?’

‘He did.’ She looked at him, her eyes sparkling with mischief, then she laughed and hugged him to her breasts. ‘Oh darling – the look on your face! Do I make you jealous?’

‘Yes.’ Hargreave grinned sheepishly. It was almost true.

‘I’m so glad!’ She rocked him, then collapsed back and stroked her fingertip across his eyebrow. ‘Oh, you’re such a nice man. Such a nice English gentleman. I think I love you …’

It seemed that his heart turned over. It felt as if he loved her too.

And his mind formed images of her working out in her school gymnasium, leaping off springboards, flying through the air, doing somersaults, cavorting on the parallel bars.

‘Can you really do all that stuff?’

‘Oh, yes, I was in competitions. I was quite good, but not good enough to be famous, my breasts were too big, even when I was fifteen. But I won some prizes. Shall I show you how I can walk on my hands?’

‘With all that wine inside you?’

‘No problem.’ She got off the bed, did a cartwheel across the room, then sprang on to her hands. She balanced there a moment, her body straight, her legs rigid, her toes pointed, her hair sweeping the floor: then she bent her knees and walked across the carpet on her hands. ‘Yes?’ she grinned at him, upside-down.

‘Very good.’

‘And now …’ She stopped, straightened her legs again, then parted them into a Y; then she dramatically raised one hand. She lifted her arm out sideways, her fingertips pointed. ‘Yes?’

‘Amazing!’

She carefully replaced her hand on the floor, brought her legs together, and did a nimble spring. She landed on her feet in a flash of golden locks, her face flushed. ‘You want to make love like that?’

‘I can’t wait!’

‘Here I come!’ She ran across the room and took a flying dive on to the bed, laughing.

‘Oh …’ He looked at her lying there beside him in the elegant room, her hair awry across the crumpled pillow, the China night out there, and it was hard to imagine her in a sexless smock toiling in an aluminium factory in the winter making pots and pans, living in a tiny grey apartment in a vast, smog-bound, joyless city: she was an exotic creature of the sun and sea and glittering nightlife, how could such beauty be caged in a factory?

‘I could not live like that any more. And that is why I decided to fuck my way to freedom.’

Fuck her way? He had not heard this last weekend.

‘What other way is there for a girl in the aluminium works? Everybody was fucking everybody anyway, what else was there to do? But I did not fuck my shift-boss and my floor manager like the other girls just to get a little more overtime on my ticket, not even the factory manager, although he begged me many times. No, I fucked the Party Secretary, because I wanted him to help me get to school to study to be a vet. That is how everything works in Russia – you must know somebody in the Party who knows somebody in veterinary school. And that is how the KGB man got to hear of me, saying he was from Mosfilm.’

‘Did you have to go to bed with him too?’

‘Of course. It was all a trick. But I thought I was going to be a movie star.’ She fluttered her eyelashes. ‘And here I am, darling, in bed with you. What secrets have you got to tell me?’

It was even exotic that she was a courtesan, a woman of the flesh, doubtless one of the most beautiful of her trade in the world, that she came from that earthy, sultry other-world, that she possessed a wealth of carnal expertise. What she was giving him would be the envy of any red-blooded man, and it did not even seem that he was paying for it. It did not spoil the atmosphere a jot when there was a knock on the door on the first morning and there stood Vladimir, looking annoyed.

‘Oh, I’m sorry, darling,’ Olga said to Hargreave, ‘I forgot – the money.’ They had just finished making love and she was dressing for breakfast, screwing an earring into her lobe. She delved into her weekend bag and produced a credit-card machine. ‘I was supposed to leave the credit-slip downstairs last night for Vladimir, but I got –’ she made her eyes sparkle – ‘excited.’

Hargreave was not embarrassed but he did not like Vladimir standing there in the doorway like a hood.

Olga ran the card through the machine, filled in the amount, and gave him the slip to sign. He noticed she had only charged him for two nights. He did not query it, but Vladimir did.

‘How many nights you pay for, sir?’

‘Two,’ Olga said emphatically, ‘last night and tonight.’

Vladimir said to Hargreave: ‘Do you go home on Sunday?’

‘Maybe,’ Hargreave said. He had no intention of leaving until Monday morning.

‘No, he goes on Monday,’ Olga said archly. ‘But this Sunday is my day off, I can do what I like on my one Sunday a month. Thank you, goodbye.’

Vladimir began to argue in Russian, Olga replied rapidly and closed the door on him. She turned to Hargreave. ‘What cheek! He says if he sees you here on Sunday you must pay for another night. I told him to go to hell.’

Hargreave did not want any trouble. ‘I’ll pay.’

‘No! Tomorrow is my one day off in a month.’ She smiled at him dazzlingly. ‘I told you I would give you a discount and I have – thirty-three per cent! You get three nights for two!’

‘It’s a bargain,’ Hargreave smiled, ‘but I don’t want trouble; I think I’d better pay.’

‘No, I told him it was against your principles to make love on a Sunday!’ She entwined her hands behind his neck and smiled. ‘But I think we will, huh, just to cheat Vladimir? We’re going to have a lovely time!’

They did have a lovely time. The previous weekend he had thought was wildly erotic, enchanting, exotic, he had felt smitten: but this weekend it really felt as if he was falling in love. Hargreave knew enough about life to know that this could not possibly be true; he knew it was only a case of wild infatuation, of joyful lust, but love is how it felt and he did not want to analyse it, he did not want to question his happiness.

That Saturday they did not leave the Bella Mar. He wanted to take her out and walk along the esplanade with her hand-in-hand, to ride in a trishaw, take her to a smart bar, a fashionable restaurant, to parade her, show her off. That’s how Hargreave felt; he wanted people to turn to stare at her beauty, he wanted the whole world to know she was his girl, to envy the fun they were having being together. But it might have been unwise: Olga could be anybody, just a tourist, but they might meet a friend of his and though Hargreave was now a free man who could do as he damn-well liked, perhaps it would be unwise for the Director of Public Prosecutions to flaunt his affair just yet. And he did not want to waste the time that could be spent making wildly erotic love.

It was almost lunchtime when they went down the sweeping old colonial staircase to breakfast beside the sparkling pool. There was nobody he knew. When she shed her robe to dive into the pool all eyes were on her magnificence. To Hargreave it was the happiest thing in the world, almost incredible, that that beautiful body was his, that an hour ago this gorgeous girl had been naked beneath him – it was almost unbelievable how lucky he was. When she took a running dive at the pool, her flaxen hair flying, all eyes were on her, riveted by her femininity, smiling at her exuberance. And when she had swum her ten lengths and heaved herself out, the water gushing off her, her long hair plastered, and walked unselfconsciously towards him, a spectacle of young womanhood, he no longer wanted to take her out of the hotel to show her off, he did not want to go any distance from that suite upstairs with its big double bed. So the champagne breakfast evolved into a long lunch while they talked and talked, and laughed, telling each other about themselves, undergoing the delightfully important business of getting to know each other. When they were full of good food and wine and sun she said, ‘Let’s go and make love,’ and as she walked across the terrace he could feel all eyes on her, he could almost hear the men sighing, and he was immensely proud of her. It did not feel as if she was bought and paid for; it felt as if she was really his.

Later, lying spent on the bed in each other’s arms, in the quietness of afterlove, she said: ‘Are you worried that one of your friends will see you, with a prostitute?’

No, he just felt happy. ‘Nobody is likely to know anything about you, and even if they did, so what? This is the Far East, not Whitehall in London; we’re not very judgemental out here. Anyway, don’t talk of yourself like that.’

She was silent a moment: ‘You are right. With you I am not really a prostitute. Because I want to be with you. I am sorry you must pay for today – if it was up to me you would not pay. And tomorrow,’ she squeezed him, ‘you will not pay, tomorrow I will not be a prostitute.’

‘You don’t feel like one now.’

She feigned indignation. ‘You mean I am not expert?’

‘Oh, you are.’

‘You don’t want your money back?’

‘Not so far.’

‘Okay.’ She snuggled against his shoulder and smiled. ‘I don’t feel like a prostitute either, with you. I feel I am your girl.’ She sighed. ‘Wouldn’t it be lovely to go away on a real holiday together, so I really was your girl, not the slightest bit a prostitute? Stay on a beach with palm trees and blue sea and tropical fish. I have never seen a beach like that, except in pictures. Macao’s sea is so brown, from the river. And we could live in a hut and swim all day, with snorkels, looking at the tropical fish. And maybe rent a little sailboat.’

It was a pretty thought. ‘We can do that. I can take some leave.’

‘No,’ she sighed, ‘Vladimir has our passports, in case we run away. I cannot even go to Hong Kong for a day because it says on my Macao identity card I am a “dancer”. The Hong Kong immigration people know what that means. I tried one day and they sent me hack. “You are a prostitute,” they said, “we do not allow you people in here!”’

Hargreave snorted. What hypocrisy – Hong Kong was full of prostitutes, the girlie-bars of Wanchai and Tsimshatsui were world-renowned tourist spots. ‘What did you say?’

‘I made a fuss. I said: “I am a dancer, sir! What dance do you want me to do? The rumba, the samba, the tango, rock-’n’-roll? Come out of your silly box and I will dance with you!” But they sent me back on the next ferry. I was so cross – and embarrassed. But maybe I can visit Hong Kong now because when my work-permit was extended they gave me a new identity card which says I am a singer.’

Hargreave smiled. ‘Can you really sing?’

‘Yes, not bad. Every night at the Tranquillity I sing some songs, with the band. Western songs.’

Hargreave looked at her. She had told him the first night he met her that she was a singer but he hadn’t believed her. But if it really was true, this put a rather different complexion on their relationship. ‘And what does it say on your passport?’

‘Singer.’

Hargreave grinned. ‘So that’s what you are – a professional night-club entertainer, not a prostitute!’

She smiled. ‘Okay, that’s me from now on. A famous Russian singer, like Madonna.’

‘Right, that’s what we’ll tell my friends. Do the other Russian girls at the Tranquillity sing too?’

‘No, I am the only one with a good voice. But I’m not very good, darling. But,’ she added, ‘I can also play the guitar.’

‘What songs do you sing with the guitar?’

‘I can only do about twenty-five well – Western love songs. The manager likes me to do it, if I am not busy when the other singers are resting.’

‘And does he pay you to sing?’

‘Oh yes. Fifty patacas a song. Sometimes more if the people clap loudly.’

‘Well, then, you’re a paid professional entertainer! Can you really do all those dances?’

‘Yes. The KGB taught me at my training school, so I could dance with all the foreign diplomats and steal their silly secrets. Even Scottish reels I can do, with swords on the floor. And American square-dancing, and the can-can, even belly-dancing. Next time I will show you, I will bring some music and my belly-dancing stuff. Even the ruby for my navel.’

Oh yes, he would love to see her do all that. And he was impressed by her accomplishments. She said: ‘Are you a good dancer, darling?’

The foxtrot and the waltz were about Hargreave’s speed. ‘Liz did try to teach me the tango. But she gave up.’

‘I will teach you to tango, darling, it is my favourite dance – so dramatic. I have all the music, on my cassettes, I will bring them next time. Would you like to go dancing tonight, I’ll start teaching you?’

Hargreave wanted to do whatever she wanted. ‘Only trouble is I don’t want to get out of this bed. And I don’t want you to put clothes on.’

‘But I better get dressed for dinner, darling, in case we meet somebody you know!’

That Saturday night they did meet somebody Hargreave knew. They were sitting at the bar off the reception hall, having a drink before dinner, when Jake McAdam and Max Popodopolous came in with Judge Peterson. The judge slapped him on the back in passing.

‘Hullo, Dave!’ Hargreave said. ‘Hullo, Jake, Max!’

They waved and went on their way. They all glanced at Olga appreciatively. They sat down at a corner table overlooking the terrace.

‘Does it matter?’ Olga asked.

‘No.’ He grinned. ‘Anyway, you’re a professional singer, remember?’

‘But will they guess what I really am?’

They might guess but he didn’t give a damn: how were they to know she wasn’t a legitimate night-club singer? He almost believed it himself now. It was possible one of them had been to the Tranquillity and remembered her – she wasn’t easily forgettable – but what the hell, they were all his friends.

‘No, they won’t guess.’

‘The fattish, Portuguese-looking one, I’ve seen him at the Tranquillity.’

Yes, Max was a bit of a bon vivant who let his hair down occasionally in questionable night-clubs. Hargreave said: ‘He’s one of my closest friends, in fact he’s my personal lawyer, he won’t talk – or care. I’d like you to meet him, and Jake McAdam, too, the tall one.’ In fact he’d like her to meet all his friends; he wanted to say, ‘This is my girl Olga Romalova, she’s a night-club singer, maybe she used to be on the game but not any more, take her or leave her but she’s my girl.’ He said: ‘Jake, he’s got a tragic story. He fell in love with a smashing American girl about ten years ago, a newspaper reporter from New York who came out here to write a story about Hong Kong corruption. She was killed in a typhoon.’

‘Oh. What a sad story.’

And there was an even sadder story that he couldn’t tell her because of the Official Secrets Act. Long before the American girl, Jake had fallen in love with a Chinese Communist schoolmistress, and that had also ended in tragedy because Jake had been a senior policeman in Special Branch.

Olga said: ‘And now, is he married?’

‘Used to be. Twice, to the same woman. But it ended in divorce both times.’ He nodded over his shoulder. ‘And the other one, Dave, he’s a judge, also divorced. We stick together, us bachelors. Go to the races together.’

‘And Jake, what work does he do?’

‘He’s a businessman. Builds boats. And he’s got an import–export business. Does quite a lot of business with Russia, everything from pins to diesel engines, I gather. And now he’s gone into politics. He’s one of those idealistic diehards who think that Britain should never have agreed to surrender Hong Kong to China in 1997. He thinks we should only give them back the New Territories when the lease expires and hold them back at Boundary Street. He says we can survive like Gibraltar does. Of course, it’s too late now, because the handover has been negotiated, but he thinks the British Government shouldn’t have mentioned the subject, that Maggie Thatcher made a mistake. But having started negotiations, we should have stuck to our guns at Boundary Street.’

She nodded pensively, stirring her pina colada. ‘And what do you think?’

Hargreave shook his head. ‘China wouldn’t have backed down like Spain did because it’s a matter of “face”. Hong Kong is the holy soil of China stolen from the Celestial Kingdom during the wicked Opium War, et cetera. Do you know about that?’

Olga sucked the pina colada off the end of her straw. ‘Sure. 1841. I’ve read some books about China. It’s true – Britain did steal Hong Kong to force China to accept the opium trade. It is a shameful story, to force people to buy drugs like that.’

‘Well, it was a long time ago, and people thought differently then.’ But Hargreave was impressed. This was your ordinary prostitute? No, a thousand times no. How many books had he read on Russia? None. ‘Anyway, now Jake is a vociferous democrat – he’s campaigning for a seat in the Legislative Council elections and his platform is we must have complete entrenched democracy to withstand the Chinese Government after 1997 and that Britain must support us with a garrison stationed here.’ He added, ‘Jake’s one of the few non-Chinese standing in the selection. As an independent.’

‘Do you think he will win?’

‘He’s very highly thought of. But it won’t do him much good – when China takes over he’s likely to be one of the first to be thrown in jail as a subversive.’

‘What kind of trouble will he make?’

Hargreave sighed. ‘China has already announced that she’ll throw out our Legislative Council the day she takes over Hong Kong. Jake and others like him will refuse to accept that because it will be contrary to the Basic Law and the Joint Declaration. That’ll land him in jail.’

‘Oh dear,’ Olga said. ‘Such a brave man. Oh dear. And you, darling – what are you going to do in 1997?’

Hargreave did not want to think about it. Ten years ago when the Joint Declaration was signed he’d had hope that English law would survive in Hong Kong, that there would be democracy, but the massacre in Tiananmen Square in 1989 had proved that was a pipe-dream and he had decided to quit in 1997, go somewhere like Spain where he could live modestly on his pension. Three years ago when things started going badly between him and Liz and there was talk of divorce, he felt like doing that even sooner. But now her lawyer’s letter had arrived, the reality of divorce under Californian law of Community of Property was upon him and his investments would be very modest when cut in half. So he would have to get a job somewhere. The only alternative was to continue to work under the new government and hope that China didn’t throw him in jail for refusing to bend the Rule of Law when they demanded. That was the bleak prospect he had faced last weekend when the lawyer’s letter arrived and he had jumped on the hydrofoil to Macao.

‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘I want to leave, but divorce is an expensive business.’

She said sympathetically, ‘Could you get a job as a lawyer in England?’

‘I could, but I’m a colonial boy now, used to the sun. Cold, grey, rainy England? And the dreadful cost of booze?’

‘I understand. I love Russia, but it will be grey for a long time, and I am very tired of grey, I am a sun girl. But you know what I think I would do if I was a businessman? I would invest in Russia.’ She raised her eyebrows. ‘Russia needs everything. Communism was so bad that Russia has nothing, not even enough food to eat. You can sell anything in Russia.’

‘I couldn’t sell a damn thing. But Jake McAdam does well there.’

‘You know what I will do with my money?’ She took his hand earnestly. ‘I have over thirty thousand US dollars saved. I am going to buy an apartment in Moscow, on the west side. Because Moscow is going to go voom –’ she exploded her hands – ‘because so many foreigners are coming now that Communism is finished. And I am going to make a lot of profit when I sell it. And you know what I am going to do with it?’

‘What?’

‘Buy some farmland. My father was such a good farmer, and he taught me. And the Russian Government is saying, buy land and be good farmers. But my father was frightened of the responsibility because he only knew the Collective where the state pays for everything. My brother was the same. But I am going to buy some land for my stupid brother and me, and we’ll have our own ducks and chickens and cows and pigs and rabbits and vegetables and we’ll sell them in the market for the real price – and you know what else we’ll have?’

‘What?’ Her enthusiasm was endearing and infectious.

‘Horses! I love horses. And we’ll build a nice, proper house, with a real toilet and bathroom! No more kettles for the tub on Saturday. No more shitting outside in the little house.’

Hargreave grinned. He glanced over his shoulder to see if his friends had heard, but they had moved. ‘Say that again, not everybody heard it all.’

‘What?’ Then she smiled. ‘Okay, a bit loud, huh?’

Hargreave grinned: ‘Was it really like that?’

‘Shit yes!’ Then she clapped her hand over her mouth and burst into giggles. ‘Oh, I’m sorry.’ They laughed together so everybody looked at them. When they subsided she leant forward and whispered in his ear:

‘Let’s go’n dance downstairs …’

And did they dance?

Hargreave had no intention of dancing more than just enough to humour her, to be romantic, but Olga had her own ideas. ‘I’ve got my dancing feet on!’ The Bella Mar, with its dance-floor beside the pool, was a rather sedate Old China-Hand place, the elderly Chinese band given to waltzes and a bit of modest rock’n’roll occasionally just to show they weren’t totally old-fashioned. But Olga Romalova, after the first rock-’n’-roll – which Hargreave performed quite well – called across to the band: ‘Hey, can you do a tango?’

‘The tango!’ The Chinese bandleader beamed, and his men struck up.

‘Der-der-der-DA!’ Olga cried, and she swept back into Hargreave’s astonished arms and leant back so her blonde hair swept the floor. ‘Der-der-der-DA –’ and she swung upright and clasped him dramatically; then she swirled away – ‘Der-der-darra-darra-der-der-Da!’

And so Olga Romalova taught Hargreave the tango. Everybody left the floor when they started – nobody knew the dance, it seemed. But Olga Romalova sure did. At first Hargreave was mortified and tried to lead her off the floor but she had cried ‘No way!’ and pulled him back. And so Alistair Hargreave, Director of Public Prosecutions, was forced to dance the tango with the most beautiful woman in the world – and he found he could.

He could! Liz had declared him a failure, but with this glorious woman in his arms, laughing into his eyes, whispering instructions, everything that Liz had tried to teach him came flooding back with the drama of the beat, and with Olga leading him it seemed he knew what to do. So there was Al Hargreave sweeping earnestly round the terrace of the Bella Mar, doing the tango very creditably with the most exotic of partners, her hair sweeping, her breasts jutting, her long legs stalking, her back arching. And when the number ended, and fifty tourists burst into applause, it was Olga who led it, clapping her hands and laughing to the crowd.

‘Didn’t he dance good?’

There were shouts of ‘Yes’ and Hargreave was blushing as he laughed. Up there on the balcony McAdam and Judge Peterson and Max were clapping.