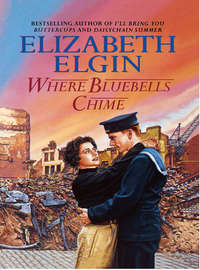

Where Bluebells Chime

‘’Night, Mr Catchpole. Take care.’

Reichmarshal Goering had sent a signal to his commanders that his Luftwaffe was to rid the skies of the Royal Air Force, though how the papers knew what Goering was saying to his underlings, or how our own fighter pilots knew the German bombers were on their way – as soon as they had taken off, almost – no one rightly knew. All the man in the street could be sure of – and the Ministry of Information could, sometimes, get it right – was that for every fighter we lost, the Luftwaffe paid three of their bombers for it. Talk even had it that one German bomber ace had asked Goering for a squadron of Spitfires to protect them on their raids over the south of England and that fat Hermann Goering hadn’t been best pleased about the request!

Only talk, maybe, but it lifted people’s hearts. Because we were not only going to put a stop to German air raids, Mr Churchill had growled in one of his broadcasts to the nation; we were going to win the war, as well! Even though we might have to fight on the beaches and in the streets we would never give in. And such was his confidence, his tenacity, his utter loathing for Hitler, that people believed him completely – about not surrendering, that was – though how we were going to win the war and when, took a little more time to digest. And as farmers and land girls cut wheat and barley and oats, battles raged in the sky above them – dogfights, with fields in the south littered with crippled German bombers. They became so familiar a sight that small boys stopped taking pieces as souvenirs and returned to more absorbing things such as searching for conkers, raiding apple orchards and queueing at the sweet shops when rumours of a delivery of gobstoppers circulated the streets.

Yet hadn’t Mr Churchill warned, years ago, that Germany was becoming too strong and too arrogant and no one took a bit of notice of him, except to call him a warmonger? He’d been right, though, people reluctantly admitted.

So now the entire country listened to what he said and believed every word he uttered. We would win this war, no matter what, because good old Winston said so. One day, that was.

11

My darling Daisy,

Thank you for the birthday card. I did as you told me and didn’t open it until the twelfth.

Once, we thought we would be together for my twenty-third birthday and the two of us house hunting and planning a wedding. Instead, you are going into the Forces and it seems immoral, almost, that I am away from it all and that we who need each other so much cannot be together. So I promise you this my lovely girl – somehow I will get home. There has got to be a way.

‘Keth, no!’ Daisy whispered. ‘Don’t do anything stupid – oh, please.’

She screwed up her eyes tightly, refusing to weep. There were thousands of women whose man had gone away and might never come home again; at least Keth was not in uniform and was safe in a neutral country, though Dada said it was a peculiar kind of neutrality that sent us tanks and guns and food and asked no payment in return. The Americans would get their fingers burned taking such risks, if anybody was interested in what he thought, and it would need only one incident at sea and before they knew it, America would be drawn into the war. Remember the Lusitania last time?

‘But would it be such a bad thing for us to have an ally?’ Mam had wanted to know, and Daisy supposed that for us, beleaguered as we were, to have someone on our side would be nothing short of a miracle.

But why should the United States become involved again? They had the wide span of the Atlantic between them and Europe. They were far enough away from Hitler so why should Bas, even though he was half-English, help fight our war?

Daisy jumped impatiently to her feet to stand at the wide-open window, gazing out into the August evening.

At least the weather was kind. There had been little rain for weeks. A farmer who hadn’t got his harvest in wasn’t trying, Dada said. And why, she demanded irritably, had she been so stupid; why was she leaving her home, her parents? Why had she lost her temper that dinnertime because an arrogant woman and her totally unimportant account upset her?

Because she was her father’s daughter, Mam said; because she had the same stubborn streak in her and his quick temper, too.

Mam understood about being in love. Mam was silly and sentimental, too; had buttercups pressed in her Bible, still, just as her daughter pressed a daisychain between the pages of the Song of Solomon beside words written for a lover, by a lover. ‘Rise up, my love, my fair one, and come away’; words about winter being past and flowers appearing and birds singing, yet now it sometimes seemed as if flowers had never bloomed and birds would never sing again. But nothing lasted, Mam said; neither bad times nor, sadly, good.

‘Our time will come, Keth,’ she whispered. ‘We’ll be together again, one day …’

The telephone began to ring, calling her back from her dreamings.

‘For you,’ Alice called. ‘It’s Tatiana.’

‘Hi, Tatty,’ Daisy smiled into the receiver. ‘What’s news?’

‘The dance tomorrow night at Creesby – okay?’ Tatiana Sutton’s voice was low and husky as if she were whispering into the mouthpiece. ‘I’m going with you and Gracie – all right?’

‘But I’m not going.’

‘That doesn’t matter. I don’t suppose Tim and I will be there, either. But if he isn’t on ops. – and there’s a good chance he won’t be – I’ll need an alibi.’

‘But couldn’t you just say you were coming over to Keeper’s?’

‘And have Mother ring me to check up? She might. She’s getting suspicious.’

‘Okay. It’s Creesby, then. But be careful, Tatty – you know what I mean? ‘Bye …’

‘And what did Tatiana want, or shouldn’t I ask?’ Alice fixed her daughter with a stare, one eyebrow raised.

‘No you shouldn’t ask, Mam, but I’ll tell you. She’s meeting Tim Thomson and she wanted to know if I’ll be at the Creesby dance on Wednesday. Her mother’s a bit stuffy about her going there.’

‘So she told her mother that you were going?’

‘Yes.’

‘But you aren’t, Daisy. It’s your medical the day after. Now you mustn’t get drawn into things!’

‘Mam, Tatty knows what she’s doing. And I don’t know why her mother tries to wrap her in cotton wool all the time.’

‘Happen it’s the way Russian mothers do it.’

‘Well, it’s stupid of her because Tatty’s as English as I am! And Tim’s a decent sort, though I don’t suppose Grandmother Petrovska would approve of him.’

‘What do you mean – approve?’ Alice looked alarmed. ‘Are things getting serious between them?’

‘Don’t think so, but you know what Tatty’s like. If it’s got anything to do with aeroplanes or aircrew, she’s mad about it. And Tim’s a good dancer, too.’

She turned to fidget with the cutlery on the table, straightening it, shifting the cruet so her mother should not see the flush that stained her cheeks. Mam knew she always went red when she told a lie, and Tatty was serious about Tim. Head over heels, truth known.

‘I still think she’s too young to be out alone.’

‘She’s eighteen, Mam!’

‘Yes, but she’s so – so unworldly to my way of thinking. They should have sent her to school instead of having that governess teach her; let her see how the other half lives!’

‘There’s nothing wrong with Tatty. And what’s that? Smells good.’ Deftly she steered the conversation into safer channels as her mother took a pie from the oven.

‘Woolton pie. Again.’ Once she’d have been ashamed to serve such a poor dish, but needs must these days. There had been a small piece of meat left over from Sunday dinner and a jug of good gravy, so a little meat, gravy, and a lot of vegetables were covered with a suet crust and heaven only knew what they would do if suet went on the ration! She glanced towards the window as the barking of dogs told her her husband was home. ‘Get the plates out of the oven, there’s a good girl, whilst I strain the carrots. And, Daisy – tell Tatiana to be careful. You know what I mean …?’

‘She is careful, Mam.’

‘Yes – well that’s as maybe.’ Alice had not forgotten what it was like to be eighteen and in love. She offered her cheek, smiling, for Tom’s kiss.

Come to think of it, she was still in love.

‘Sorry I’m late, Mr Catchpole.’ Gracie arrived, breathless, pulling her bounty behind her. ‘Found it in Brattocks Wood. It looks good and dry – thought it would do for the fire. Hope it was all right to take it?’

‘Course it was, as long as nobody saw you with it.’ Jack regarded the branch of fallen wood. ‘Get it stuck behind the shed and us’ll get the saw to it later. And Miss Julia was asking for you.’

‘I’ve seen her. Home Farm is letting her have six pullets so she’s going into Creesby to the Food Office and getting their egg coupons changed to hen-meal coupons. Seems there’s a shed at the back of Keeper’s Cottage that no one uses. Said it needs a bit of repairing and she asked me to – er – mention it to you.’

‘And I suppose her expects me to see to it? Well, I’m a gardener; no good with hammer and nails. You’d best see Will Stubbs – he’s the handyman.’ Jack shook his head mournfully. ‘I mind the time when there was an estate carpenter here, but not any longer. And when you see Will Stubbs, tell him as how Miss Julia’ll need chicken wire and posts for them birds. I suppose Alice Dwerryhouse doesn’t mind having hens in the shed at the back?’

‘Don’t think so, Mr C. Mrs Sutton said that Daisy’s mam would be saving her scraps and peelings for me.’

‘And where are you goin’ to boil the stuff for the hen mash, then?’

‘We-e-ll – I did suggest the potting-shed fire, for the time being. After all,’ she hastened, ‘that would give you first refusal of the hen muck when I clean out the shed each week. Would only be fair,’ she stressed.

‘Fair.’ Jack Catchpole coveted the droppings to make into liquid manure. When it came to fertilizers, hen droppings were in a class of their own. ‘You got a pan for the fire, then?’

‘No, but Mrs Sutton is sure there are old iron pans they used to use at Rowangarth before they got a gas stove. I’m to have a word with Cook about it. Tilda never throws anything away, I believe.’

‘So it’s all cut and dried, Gracie,’ he murmured, relieved the hens would be housed well away from his garden.

‘Almost. I’m really looking forward to having them.’

‘Do you like it here, lass? Are you going to settle?’

‘Oh, yes! I knew it the day I came. No complaints, I hope? I’m doing my best,’ she added anxiously.

‘Aye. You’m a trier, I’ll say that for you, and as long as you see to it that I get that hen muck and don’t let Tom Dwerryhouse get his hands on it, I won’t grumble.’

Gracie let go a sigh of pure contentment. Of course she was going to settle at Rowangarth – for the duration, if she had anything to do with it. She loved living in the country; even in winter when it would be cold and wet and muddy she would still love it. She liked the land girls in the bothy, too, and the food was every bit as good as Mam’s. And Daisy and Tatty were nice and Drew was lovely and not a bit snobby like she’d thought a sir would be. And then she felt a terrible sense of guilt.

‘Oh dear, Mr C. I’m enjoying this war and I shouldn’t be, should I?’

‘Happen not, lass.’ He gave her shoulder a brief, fatherly pat. ‘But take my advice and make the most of the good days, ’cause for every good day, there could well be a bad one. Now get that branch out of sight like I told you and let’s get on with some work. Have you ever clipped a box hedge, Gracie?’

‘I haven’t, Mr Catchpole.’ Until she came to Rowangarth she hadn’t even seen a box hedge.

‘Then today, lass, you’m about to learn!’

‘You aren’t one bit interested in my medical, are you, Tatty? You’re miles away.’

‘No, Daisy, I’m not – not miles away, I mean. But they’ve been doing circuits and bumps all day at Holdenby Moor and you know what that means?’

‘Mm.’ Bombers taking off, doing two or three circuits of the aerodrome, then landing. Flight-testing the aircraft, which was always a giveaway that they’d be operational that night. ‘But they mightn’t go, Tatty.’

‘They’ll go, all right. There’s no moon at all – not until the new one on Tuesday. Perfect flying conditions.’

‘Fine. They’ll have good cover, then. Fighters won’t find them so easily. Don’t worry so, please. It’s the Air Ministry’s job to worry about flying conditions and it’s yours to wish Tim luck every inch of the way; get him back safely. And Tatty – try not to get too involved.’

‘Why? Because he’s a tail-gunner and gunners get killed, even when the rest of the crew make it back? And why shouldn’t I get involved? Why did you get involved with Keth?’

‘Because I love him.’ It was as simple as that.

‘And I’m not capable of falling in love, is that what you’re trying to say?’

‘No! But I’ve known Keth all my life. He’s always been there. When did you meet Tim? You hardly know him!’

‘You know when I met him! I’ve known him thirty-seven days exactly. And I loved him the minute I saw him and now it’s more serious than that.’

‘Oh, my Lord – you haven’t …?’

‘No we haven’t, but we will, Daisy. It nearly happened on Wednesday night. We both of us know it will, one day soon. And don’t look at me all holier than thou, as if I’m a common little tart! If you loved Keth as much as I love Tim, you’d understand.’

‘Tatty! I’m not judging you – truly I’m not. And anyway, the pot doesn’t call the kettle black!’

‘You mean you and Keth – you’ve …?’

‘Been lovers? Yes. When Keth came home because he thought there was going to be a war – the summer of ’thirty-eight it was. It happened before he went back to America to college.’

‘And was it marvellous? Was it worth it – all the worry? Because I know I shall worry – looking Mother in the face afterwards, I mean. Funnily enough, I’m not so bothered about getting pregnant because Tim says he wouldn’t let it happen. And you didn’t get pregnant, did you?’

‘Tatiana Sutton! You are so innocent!’

‘I suppose I am, but I trust Tim.’

‘Oh, famous last words! Please, please be careful? And make sure Karl doesn’t catch you out. You know he’s always hovering.’

‘Karl’s getting old now. I can give him the slip any time I want to.’

They had come to the crossroads, to where a signpost once stood with ‘Holdenby 11/4’ on one arm and ‘Creesby 5’ on the other. Only signposts weren’t allowed now, because of the invasion, nor names on railway stations.

‘I’ll be careful. Both of us will. And, Daisy – was it marvellous? If you were me – would you?’

‘You’ll be taking an awful risk, you know that? And I can’t advise you now, can I? Your circumstances and Tim’s – well, they’re a whole lot different to ours. There’s a war on now.’

‘I know there is. And it wasn’t fair of me to ask, was it?’ She gave a little shrug of despair. ‘Well – good night, then. Is tomorrow your half-day off, Daisy? Will I see you?’

‘It is, but let’s leave it? You’ll probably be meeting Tim, anyway.’

‘God, I hope so!’

‘Of course you will! Tim will be just fine. And you don’t know for sure he’ll be on ops. tonight. Want me to walk to the gates with you?’

‘No thanks. I’ll be all right. I’m a big girl now – really I am.’

‘Hmm.’ Daisy watched her walk away into the twilight, shoulders drooping. Oh, damn this war and damn the stupid politicians who let it happen! Old men, all of them! Just declared war, they had, then expected the young men to fight it! ‘Hey, Tatty!’ she called.

‘Yes?’ Tatiana stopped, then turned slowly.

‘It was marvellous! Good night, love.’

Tatiana smiled suddenly, brilliantly. Then she turned, head high, shoulders straight and walked with swinging stride towards the gates of Denniston House.

Good old Tatty, Daisy smiled. She still hadn’t told her about the medical, but what the heck? Medicals were two a penny. And she had passed, anyway. She had known she would. Now all she had to do was wait until They sent for her.

She crossed the field where only yesterday sheaves of wheat had stood in stooks, drying. Today they had been piled high on carts and stored to await threshing after Christmas. She winced as the sharp stubble scratched her feet through her sandals then thankfully climbed the fence into Brattocks Wood. Here, in the shifting half-light, the wood was settling down for the night. She squinted at her watch but could not see the time. About ten o’clock, she supposed. Not a light was to be seen. Official blackout time tonight was 8.31, though it would not be completely dark for a little while. Yet despite the extra hour of daylight the nights were drawing in now. Soon the leaves would begin to yellow and then would follow the misty mornings, with swallows chattering on the telegraph wires, making ready to fly away.

Clever little birds. They came in May and left, suddenly, when they knew the time was right. The war made no difference to their migrations. Swallows didn’t know about war.

A hunting owl screeched to frighten its prey into movement, and Daisy began to run towards Keeper’s Cottage.

‘Watch the blackout, lass,’ Tom warned as she opened the kitchen door. ‘Want to get us all locked up, do you?’ He glanced pointedly at the mantel clock. ‘And what time of night is this to be coming in?’

‘Nearly half-past ten, Dada. The little hand is on ten and the big one on five,’ she grinned mischievously. ‘I’ve been with Tatty – just walking and talking …’

‘Didn’t you see your Aunt Julia? She’s just this minute left.’

‘No. I came across the field and through Brattocks.’

‘And what have I told you about being in the wood alone at night? Anything could happen to you!’

‘Dada! I know Brattocks like the back of my hand – even in the dark.’

‘Happen you do, but you’ll come home down the lane in future, especially now the nights are drawing in. I could tell you things about that wood –’

‘What your dada means is that you could have been taken for a poacher,’ Alice interrupted hastily. ‘Or you could come across a tramp … Your Aunt Julia came to tell us about Drew. Seems his ship is based in Liverpool, so he’ll be nice and near when he gets leave. Only three hours by train to York. HMS Penrose, he’s on. We have to write to him care of GPO London, so no one will know where the Penrose is.’

‘But we do know, Mam, though I can’t believe Drew would say a thing like that over the phone.’

‘No. Seems the phone rang and Winnie on the exchange asked Julia if she would accept a trunk call, reversed charges. And it was Drew. Gave her his address and said they were tied up alongside, that was why he’d been able to ring, see? But he didn’t say alongside where. Then the minute Julia put the phone down it rang again. “Did you get your trunk call all right?” Winnie asked. And when your Aunt Julia said she had, Winnie dropped her voice all dramatic, like, and whispered, “Well, it was from Liverpool, but not a word to a soul, mind.”’

They all laughed, because it was good to hear from Drew and that he had sounded happy and sent his love and asked them all to write.

‘But not a word about this!’ Alice was all at once serious. ‘We’re family so we’re entitled to know, but we don’t shout all over the Riding where Drew’s ship is and what he’s doing. Drew has been lucky. He could have been sent all the way up to Scapa Flow – or even overseas. And the Germans haven’t bombed Liverpool much, so far. Not like when he was in barracks. I’m glad he’s left Plymouth.’

‘Hmm. Wonder where I’ll end up, Mam?’

‘What do you mean, Daisy – end up? You’ve only just had your medical. They told you it might be quite a while before you get your call-up papers.’

And then Alice’s blood ran cold and she wondered why she had never thought of it until now. Because they could well send Daisy down south where all the air raids were; where the fighter stations were being bombed and strafed day after day.

They could send her to Dover, which was being shelled from across the Channel every day, or to Plymouth or Portsmouth, where the invasion would be – if it came …

12

Julia unlocked the door of the room she had not entered for exactly a year. Next to it was the sewing-room where Alice once worked; the small back room in which they had shared secrets almost too long ago to remember. And this room – Julia slipped the key into her pocket – was Andrew’s surgery. Major Andrew MacMalcolm of the Medical Corps, killed just six days before the conflict they called the Great War ended. In this room she had created a sentimental replica of Andrew’s London surgery; a shrine, almost. Every piece of furniture, every book, pencil and instrument – even the grinning skeleton and the optical wall chart – had been brought here.

Once, she had found comfort from it; sat at his desk, picked up his stethoscope, willed him to walk through the door. Now she came here only once a year, on the last day of August.

She dusted the desktop, the chair, lifted the sheet that covered the skeleton then let it drop as she heard a footstep in the passage outside. Slowly, gently the door knob turned, then Nathan was standing there, eyes sad.

‘Sorry, darling. I’m not prying …’

‘Then why are you here?’ Julia was angry, not only at the intrusion into her other life, but that Nathan should witness this rite of remembrance.

‘I suppose because I thought you might need me. I do understand. Today would have been his birthday.’

‘Yes.’ The last day of August. Andrew had lived for just a little over thirty-one years. Today he would have been fifty-three and a consultant physician, maybe, or a surgeon; a father, certainly – perhaps even a grandfather. One year older than Nathan, who had neither son nor grandson because he had loved a woman who clung stubbornly to the memory of another man. ‘And very soon, Nathan, you and I will have been married for two years. I threw away a lot of happiness, didn’t I, being bitter? Yet I can’t forget Andrew. The part of me that remembers today loves him still. Does it hurt you to hear me say it?’

‘No. Andrew was a part of your life. If I were him, I wouldn’t want you to forget.’

‘And would you have wanted me to marry again if you were dead and Andrew alive still?’

‘Yes, I would. If I’d loved you as he loved you – and I do, sweetheart – then I would have wanted you not to be alone.’

‘From heaven, would you have wanted it, Nathan?’ she whispered, aware of the goodness of him and the compassion in his eyes.

‘From that other place we have come to call heaven – yes,’ he smiled.

‘Then let me tell you – Julia MacMalcolm has gone.’ She rose from the chair in which Andrew once sat and went to stand at her husband’s side. ‘I left her at a graveside at Étaples. And now I am Julia Sutton, who has been twice lucky in love; different loves, but each of them good. Can you accept that?’

‘Easily, because you are you and headstrong and sentimental and honest. I wouldn’t change what you are or what you were. And I shall go on loving you as long as I live, just as a young nurse will always love a young doctor. Nothing can turn back love, Julia, nor diminish it.’

‘You’re a good man, Nathan. Thank you for waiting all those years for me.’

She touched his cheek with gentle fingertips. She would not kiss him, not here in Andrew’s surgery. Instead, she walked to the window, drawing across it the flimsy cotton curtains that once hung in a house in a London street called Little Britain. Then she took her husband’s hand, leading him from the room, turning the key in the lock before placing it in his hand.

‘I shall not open that door again. When Drew is next home, give the key to him, will you? He’ll understand. And, Nathan – this woman I am now loves you very much, so will you kiss me, please?’