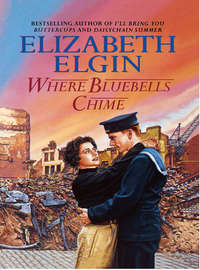

Where Bluebells Chime

‘Yes, but I know Mam and Aunt Julia didn’t like him. Even now, if ever his name is mentioned, your mother screws up her mouth like she’s sucking on a lemon. I once heard her say he’d been a womanizer – but we shouldn’t speak ill of the dead, should we, and Tatty hasn’t grown up like him, Mam says. Tatty’s okay.’

‘Yes, but Tatty’s going to have to watch it. You know how strict Aunt Anna can be and Tatty has really fallen for that air-gunner. She said she doesn’t care what happens – nobody is going to stop her seeing him. She’ll have to sneak out, tell lies.’

‘Well, I’m on Tatty’s side. Tim’s a nice young man and someone should remind Tatty’s mam that there’s a war on and that young girls don’t need chaperoning now!’

‘But Tatty’s so innocent, Daiz. She’s always been fussed over and protected. And if Aunt Anna wasn’t fussing, there was always Karl in the background to look after her.’

‘Yes, and teach her to swear in Russian,’ Daisy giggled. ‘Don’t worry about Tatty. She’ll be all right. She’s good fun – away from home. But oh, Drew, I could stand here for ever. It’s all so beautiful I can’t believe there’s a war on.’

The distant sound of aero-engines at once took up her words and made a mockery of them. A bomber flew overhead, big and black and deadly.

‘Looks as if they’re going again tonight.’ Daisy looked up, preparing to count. ‘Take care, Tim,’ she said softly as another aircraft roared over Brattocks Wood. ‘Come home safely, all of you.’

Helen Sutton sat quietly in the conservatory, watching the sun set over the stable block. It tinted the wispy night clouds to salmon pink and shaded the darkening sky to red.

Red sky at night, sailors’ delight …

Rowangarth’s sailor had gone back to his barracks on the noon train from Holdenby. Soon now he should be in barracks, then where? She shivered as the short, sharp pain stabbed inside her chest. In yesterday’s papers she had read that Somewhere in England – They always called a place Somewhere in England when it suited them not to name it – close-packed German bombers with fighter escorts had attacked harbours, fighter stations and naval bases on the south coast.

Naval bases. Plymouth and Portsmouth must surely have been targeted by the Luftwaffe. It was a part, Helen was sure, of the softening-up process so there would be less resistance when the tides were right – right for the Germans, that was. In September.

Where would Drew be then? At sea, Helen hoped fervently. He’d be safer at sea. How proud she had been today of the son Giles never lived to see, tall now, and straight and Sutton fair, with eyes grey as those of his grandfather John; like his great-uncle Edward’s, too.

Drew would come back whole from this war. Fate could not be so fiendish as to take him. Besides, Helen had spoken to Jinny Dobb at the wedding this afternoon, with Jin asking why she was so sad; telling her she was not to fret over young Sir Andrew because his aura was healthy, she insisted, and was Jin Dobb ever wrong, she’d demanded.

‘Take care of yourself, milady,’ she’d urged. ‘He’ll come back safe to claim his own, just see if he doesn’t.’

Dear Jin. Those words gave her brief comfort, Helen smiled, for sure enough, Jinny Dobb could see into the future and read palms and tarot cards – with which she, Helen, did not entirely hold. But this afternoon, at Mary’s wedding, she snatched comfort from Jin’s prophecies and smiled and waved and threw confetti when Will and Mary left Holdenby for a weekend honeymoon in quite a grand hotel in York.

Mary had looked beautiful. Blue certainly suited her and she and Tom walked solemnly down the aisle to where Will and Nathan waited. How nice, those cosy country weddings.

The door knob turned, squeaking, and Tilda walked softly to Helen’s side.

‘I’ve brought your milk and honey, milady. Miss Julia asked me not to forget it.’

‘Tilda, you shouldn’t have bothered, especially as you’ll be managing alone until Mary gets back. You’ll have all your work cut out –’

‘Oh, milady, I’ll be right as rain. There’s only you and Miss Julia and the Reverend to see to and not one of you a bit of bother. It was a grand wedding, wasn’t it, though I gave up thinking long ago that anyone’d ever get Will Stubbs down the aisle. But fair play, Mary managed it though no one can say those two rushed headlong into wedlock, now can they?’

‘Tilda!’ Helen scolded smilingly. Then raising her glass she took a sip from it. ‘And here’s wishing them all the happiness in the world!’

‘Amen to that.’ Tilda turned in the doorway. ‘You’ll think on, milady, not to forget and switch the light on?’ An illuminated conservatory would fetch every German bomber on the Dutch coast zooming in over Rowangarth and would land them with a hefty fine and a severe telling-off from the police for doing such a stupid thing.

‘I’ll remember. I think you’d better remind me tomorrow to ask Nathan to take the light bulb out.’ A conservatory was too big and awkward to black out effectively. Best take no chances. ‘And don’t wait up. Goodness knows when the pair of them will be back from Denniston. They have a key. You’ve had a long day – off to bed with you.’

And Tilda said she thought she could do with an early night, but that she would see to the doors and windows first, then check up on the blackouts.

‘Good night, milady,’ she smiled, closing the door softly behind her.

Dear Lady Helen. They would have to take good care of her for there were few left from the mould she’d been made from; precious few, indeed.

Tom Dwerryhouse hung up his army-issue gas mask, took off his glengarry cap, then leaned the rifle in the corner.

There had been an urgent parade of the Home Guard called for this evening and he and several others had had to leave the wedding early and put on their khaki for a seven o’clock muster.

It was a relief to be told that their rifles – ammunition, too – had arrived at last and he opened the long, wooden boxes only to sigh in disbelief. Those long-promised rifles – and he knew it the minute he laid eyes on them – were leftovers from the last war and had lain, it seemed, untouched and uncared for in some near-forgotten store.

He took the rifle, breaking it at the stock to squint again down the barrel. Filthy! It would take a long time to get the inside of that barrel to shine like it ought to. There would have to be a rifle inspection at every parade to let them know that Corporal Dwerryhouse wasn’t going to allow any backsliding when it came to the care of rifles, old and near-useless though they were.

He snapped it shut, gazing at it, remembering against his will when last he fired such a rifle. It was something he would never forget. He knew the exact minute he took aim, awaiting the order to fire. And his finger had coldly, calmly, squeezed the trigger that Épernay morning.

It was the bullet from his own rifle, he knew it, that took the life of the eighteen-year-old boy. Aim at the white envelope pinned to the deserter’s tunic to show them where his heart was, that firing squad had been told. But the other eleven men had been so uneasy, so shocked that he, Tom Dwerryhouse, took it upon himself to make sure the end would be quick and clean.

A sharpshooter, he had been, but an executioner they made him that day. Refuse to take part and he too would have been shot for insubordination and another, less squeamish, would have taken his place.

Then, directly afterwards, the shelling started and heaven took its revenge for the execution of an innocent and directed a scream of shells on to that killing field so the earth shook. That was when he fell, surrendering to a blackness he’d thought was death.

Rifleman Tom Dwerryhouse did not die in that Épernay dawn. He awoke to stumble dazed, in search of the army camp he did not know had been wiped out by the German barrage.

How long he walked he never remembered, but a farmer had taken him in and given him food and shelter and civilian clothes to work in. And Tom acted out the part of a shell-shocked French soldier, and those who came to the farm looked with pity at the poilu who was so shocked he uttered never a word.

The Army sent a letter to his mother, telling her he had been killed in action and his sister wrote to the hospital at Celverte, to tell Alice he was dead.

The night of that letter, Alice was taken in rape. She had not fought, she told him, because she too wanted to die, but instead she was left pregnant with the child who came to be known as Drew Sutton.

Now white-hot anger danced in front of Tom’s eyes. He flung the rifle away as though it would contaminate him and it fell with a clatter to the stone floor.

He hoped with all his heart he had broken it.

9

Tom stood hidden, unmoving. To a gamekeeper, stealth was second nature. Such a man must move without the snapping of a twig underfoot, learn to sink into night shadows or merge into sunlight dapples. It was, in part, to ensure that young gamebirds were not disturbed nor frightened unduly, but mostly that inborn stealth helped outwit poachers, out to take pheasants or partridge.

The sudden clicking of a rifle bolt was a sound he remembered well. Breath indrawn, he awaited the command he knew would follow.

‘Halt! Who goes there?’

‘Friend,’ Tom called clearly.

‘We’re armed. Step forward!’ A pinpoint of light searched him out, swept him from head to feet. ‘Put down that gun!’

‘It isn’t loaded.’ Slowly, carefully, Tom laid his shotgun at his feet.

‘You’re on army property. What are you doing here?’

‘I know I am. But it’s been Pendenys land for a long time – I’d forgotten you lot.’

‘That’s as maybe, but I want to know why you’re creeping around in the dark, and armed at that.’

‘A gamekeeper usually carries a shotgun.’ Tom had recovered his composure now. ‘And they creep around because that’s the best way to catch poachers. Meat’s on the ration, and a brace of pheasants fetches thirty bob on the black market. And if I’m on Pendenys land it’s because I often meet up with their keeper, doing his own night beat. I’m sorry. It won’t happen again.’

‘But how did you get in?’ The soldiers lowered their rifles. ‘This place is supposed to be secure.’

‘It didn’t keep me out. If it’s security you’re bothered about, I’d take a look at Brock Covert. It’s the way I always come in at night. If you’re interested, meet me in the daylight and I’ll show it to you. Name’s Tom Dwerryhouse, by the way. I’m keeper on Rowangarth land, joining this. And I was a soldier myself once; was a marksman when you two were still messing your nappies. Could have put one through your cap badge at a hundred yards!’

‘Ah, well. Got to be sure – and you shouldn’t have been here.’ The man reached into his pocket. ‘We were just going to have a quick fag. Want one?’

‘Don’t smoke, thanks. Never did. Want a sup of tea?’ Tom fished in his game bag for his vacuum flask.

‘Thanks, mate. Name’s Watson – corporal. And this one here’s Johnny.’

‘Which regiment – or shouldn’t I ask?’

‘Green Howards.’

‘Ah.’ Carefully, in the darkness, Tom filled the cap of the flask, passing it over. ‘Yorkshire mob, eh? What’s a regiment like the Greens doing here?’

‘Buggered if I know.’ They settled themselves comfortably, young soldiers and old soldier. ‘They don’t tell us anything.’

‘Nothing changes. They never did.’

‘It’s my guess the CO doesn’t know what’s going on either though he makes out he does.’

Tom refilled the cap and handed it to the soldier called Johnny, knowing that if he didn’t ask questions he would learn more.

‘It isn’t as if we’re doing anything but guard duties. Flamin’ boring, but the both of us were at Dunkirk so we aren’t complaining. This posting would suit me nicely for the duration.’

‘Reckon you both deserve a quiet number,’ Tom commiserated. ‘Dunkirk couldn’t have been a Sunday School outing, exactly.’

‘It weren’t. Ta.’ Johnny gave back the flask top.

‘Still, you’ll be all right, here,’ Tom directed his attention to the corporal, ‘though I wouldn’t fancy Pendenys as a billet. Great barn of a place.’

‘A billet? We don’t get nowhere near the place. Us lot are quartered in the stable block and the officers have been given the estate houses to kip down in. It’s them that live in the big house.’

‘Civilians.’ Johnny lit another cigarette.

‘You’re guarding civvies?’

‘We-e-ll, there’s a few military amongst them, but what they are nobody knows. Not even our CO gets inside Pendenys.’

‘There’s women, too.’ Johnny grunted derisively.

‘’S right. Fannies.’

‘There were Fannies in France in my war,’ Tom offered. First Aid Nursing Yeomanry. Brave lasses, they’d been. ‘They drove ambulances. Went right up to the front line.’

‘These lot don’t drive nothin’. They throw a nasty hand grenade, though.’

‘Fannies?’ Tom frowned. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Johnny’s seen ’em,’ nodded the corporal. ‘He’d nipped into the bushes for a Jimmy Riddle and a grenade landed not a hundred yards away. Live, it was. He got the hell out of it pretty sharpish. Could have done him a mischief.’

‘Folk around these parts,’ Tom said, ‘reckon they’re getting Pendenys Place ready for high-ups from London – when the bombing starts.’

‘Nah.’ The corporal said it was nothing like that. The King and Queen, in his opinion, would go to Balmoral if ever they left London.

‘Then it’s a rum do,’ Tom frowned.

‘Rum? It’s bloody peculiar. Some of the civvies are foreigners – leastways one of our lads heard them talking foreign. And the military in the big house don’t have any badges.’

‘No regimental insignia?’

‘Nothing at all to show which lot they belong to. But keep it shut, mate, or it’s me for the glasshouse, and ta-ta to me stripes!’

‘Not a word,’ Tom assured him gravely. ‘And if you’d like to give me a call one day – I live at Keeper’s Cottage on the Rowangarth estate – I’ll show you Brock Covert.’

‘Ar. Thanks.’ It would suit the corporal to be able to point out a breach in security where any old Tom, Dick or German could slip in. ‘Might just do that. An’ keep away from here, eh? Can’t always guarantee that us two’ll be on guard duty.’

‘I will, and thanks. Good night, lads.’

Frowning, Tom made for Brock Covert. The Green Howards, a crack regiment, guarding civilians? And soldiers who wore no regimental badges? Fannies, an’ all, who’d forsaken ambulances for grenade throwing. It was a rum do, all right.

In early August, the Luftwaffe flew over the south of England dropping not bombs, but leaflets. They fell in thick scatters and were eagerly gathered up. They detailed Adolf Hitler’s proposals for peace between Great Britain and the Third Reich and were read with amazement.

Make peace with that one? Surrender – because that’s what it would amount to – to an ex-corporal? Mad as a hatter, that’s what he was and his leaflets a waste of good paper into the bargain.

On that day, too, Telegraphist Sutton was summoned to the Regulating Office and drafted to his first ship, and an envelope bearing the words ‘On His Majesty’s Service’ dropped through the letterbox of Keeper’s Cottage. With it was a pale blue air-mail letter, its American stamp franked clearly with a Washington postmark.

So it had come. Alice gazed at the manila envelope. The WRNS had not forgotten her daughter nor lost the application she filled in in a fit of pique almost seven weeks ago.

She swallowed hard and noisily, then placed the envelopes on the mantelpiece between the clock and the tea caddy. Oh, damn this war and damn Hitler! She gazed about her helplessly, then hurried into the passage to pick up the telephone.

‘Hullo, Winnie,’ she said to the operator. ‘Give me Rowangarth, will you?’ She stood, eyes closed, breathing deeply to fight the panic inside her. ‘It’s arrived, I think,’ she said without preamble when her call was answered. ‘An OHMS letter for Daisy. It’ll be about her medical …’

‘Put the kettle on,’ said Julia Sutton. ‘I’m coming over!’

‘Where have you been, dear?’ Helen Sutton laid aside the glove she was knitting in navy-blue wool.

‘Popped over to Keeper’s. Daisy’s heard from the Wrens about her medical, Alice thinks. She and Tom were hoping they’d forgotten her.’

‘I don’t know why she had to volunteer. It’s bad enough Drew having to go.’

‘Dearest, don’t worry. She might not pass the medical.’

‘Of course she will!’

‘Yes, she will. But they mightn’t send for her for ages. And we’ve got to face it, women will all have to do war work before so very much longer and the young ones could well be sent into the Forces.’

‘But they couldn’t do that! Not to young girls. Is nothing sacred?’

‘The way things are going, Mother, it seems not. I sometimes think I should be doing more.’

‘But you and Alice go nights to the church canteen and you helped with the evacuees.’

‘The evacuees have all gone home and serving cups of tea to soldiers and airmen isn’t doing a lot for the war effort.’

‘You’re the vicar’s wife, Julia. Surely that’s work of national importance?’

‘Well I’m not so sure a vicar’s wife would be exempt from war work. If push comes to shove – and it will, before so very much longer – they could have me emptying middens if they thought it would help with the war!’

‘You can’t mean it!’ Helen picked up her needles and began knitting furiously.

‘Of course not.’ How could she be so stupid and her mother getting more frail and more afraid as each day passed? They were all afraid, but that was no excuse for upsetting her mother, who worried all the time about Drew. ‘And if they did direct women into the Forces, it would only be as clerks and typists, or cooks. They wouldn’t be in any danger, truly they wouldn’t.’

‘So when Daisy goes we shouldn’t worry too much …?’

‘Daisy will be fine, and she hasn’t gone yet.’ Her mother adored Daisy; looked on her as an extension of Drew, which in reality she was. ‘Now stop your worrying, dearest. I haven’t seen the paper yet. Anything in it worth reading?’

‘Nothing! They’ve shelled Dover – from across the Channel, Julia. Those poor people! And they’ve been bombing fighter stations on the south coast.’

‘Don’t believe all you read in the papers.’ Julia wished she hadn’t asked. ‘Tune in to the BBC. They aren’t scaremongers.’

‘I did, and their news was just as bad, so it must be true. Our fighters were waiting for the German bombers, though. They were in the air before the Luftwaffe crossed our coastline. I wonder how we know they are coming, Julia?’

‘Beats me. Probably we’ve got spies on the French coast – or something …’

Julia turned to gaze through the window, her thoughts not to be given voice, for what she had feared all along was happening. We were being softened up for that September invasion. It made sense to knock out the fighter stations first. Hitler had to get here if he was to be complete master of Europe and the daily bombings signalled the start of it. The fight for Britain was on, it would seem.

‘I shouldn’t wonder if there isn’t a letter from Drew soon, telling us he’s got a ship. I’ve written a couple of letters but I’m not posting them until we get his new address. He’ll be safer at sea, Mother, to my way of thinking. Plymouth has taken more than its fair share of the air raids.’

‘You could be right.’ Helen brightened visibly. ‘I think I’ll write to him, too.’

‘You do that, dearest. Tell him all the nice things. He likes hearing about Rowangarth.’ Home Farm starting the corn harvest, Jack Catchpole’s anger at the newly-appeared molehills on the front lawn; Tilda bottling Victoria plums to store for winter puddings, Tom’s bitch having a fine litter of puppies. ‘I wouldn’t mention the letter that came for Daisy this morning, though. She’ll want to tell Drew about that herself.’

‘Mm. And it mightn’t be about her medical, you know. Maybe it’s to tell her they’ve got enough Wrens for the time being.’

‘You could well be right.’

Julia felt unease as she watched her mother walk away; not so straight, now, her steps slow and unsteady sometimes.

Dearest lovely Mother. Once you were so beautiful, so sure and brave. War took your sons from you yet you never wavered; you cared for the entire village, were always there to comfort when the death telegrams came.

We all leaned on you, drew strength from you. You were like a safe haven. You saw to it that the old always had logs to burn in winter and that no one went entirely hungry.

Yet now you are old yourself and have been called on to face another war and what I’ll do when you leave us, what Rowangarth and the whole of Holdenby will do, I don’t dare think.

And, Mother, Daisy will have to go, sooner or later. We’ve got a long, terrible time ahead of us. We are on our own now, and women are going to have to help fight the war, whether we like it or not …

Daisy said, ‘Hi, each!’ looked up at the mantelpiece as she always did, faltered for just a second, then said, ‘Well, what d’ya know? A letter from His Majesty.’

‘Open it, love.’ Alice could wait no longer. It had lain there all day, tormenting her so much that she had thought – only for a moment, mind – of taking the kettle to it and steaming it open.

‘Albion Street, Leeds,’ Daisy studied the stereotyped form. ‘That’s where I’m to go. On the twenty-ninth of August, at half-past three.’

‘Two weeks away,’ Alice frowned.

‘So it is. If the date isn’t convenient I’m to let them know at once, reusing the envelope and the enclosed label,’ she grinned. ‘There’s economy for you!’

‘It isn’t funny,’ Alice snapped, more than ever agitated now she knew that what she had feared all day was fact. ‘And what do they mean – if it isn’t convenient?’

‘My period, I suppose. But I’ll be all right.’

‘Daisy!’ Such talk, in front of her father!

‘What’s the matter, Mam – doesn’t Dada know about the birds and the bees?’

‘That’ll do, lass.’ Impudent young miss! Tom fought to keep the smile from his lips. ‘What’s Keth got to say for himself, then?’

‘Don’t ask.’ Daisy took a knife from the table, carefully opening the envelope. ‘That’s between me and him – oooh, Mam, he’s looking at rings! What do I want, he says.’

‘Rings! I’d have thought he’d have better things to do with his money than send a ring that’ll likely end up torpedoed at the bottom of the Atlantic!’

‘Well, since he’s asking, I think I’d like a sapphire. It would go with my brooch.’

Would match the daisy-shaped brooch Aunt Julia had given her the day she was christened; petals of sapphires with a pearl at its centre. So valuable that she still had to ask Mam’s permission to wear it.

‘Your brooch, Daisy Dwerryhouse, would keep me in housekeeping for five years! Now where is Keth to find the money to match sapphires like those, will you tell me?’

‘Don’t know, Mam.’ He still hadn’t told anyone what his job was all about. ‘But he said he’s got money in the bank now. You should be pleased for him when he’s had to live from hand to mouth most of his life – and had to take the Kentucky Suttons’ charity.’

‘Charity! You call saving Bas Sutton’s life charity?’ Alice lifted the potato pan from the stove top, walking with it to the yard to strain the water over the cobbles. Scalding saltwater killed the weeds, she insisted.

‘Daisy love, don’t rile your mother. She’s all on edge these days and that letter of yours hasn’t helped.’

‘Sorry, Dada.’ She was at once contrite. ‘I’m not exactly pleased about it myself. But there’s no going back now and at least it’ll be better than working in a snobby shop. It’ll help pass the time, I suppose, till Keth gets home. Anything I can do to help?’ she asked as Alice returned.

‘Please. Be a love and get the plates out of the oven.’