You Will See Fire

Later, a photograph of his father’s hacked body—taken by a journalist who had found his way into the hospital room—was slipped to Gathenji. He would keep it in a file, along with newspaper clippings about the killing and accounts he’d taken from a handful of local women who had been snatched with his father that night. He’d tracked the women down and given assurance that he would not expose them: He just needed to know what had happened. From them, and from the account of his stepmother and younger brother Edwin, who had been at the house during the abduction, he pieced together the details.

He learned that about ten young men had converged on the house, and that some had worn the red shirts of the youth wing of the ruling party. Some were members of the campaign team of the local parliamentarian, Joseph Gatuguta, a longtime Kenyatta confidant who owed his power to the president. Some were unemployed young men to whom Samuel Gathenji had thrown construction jobs. Some were true believers, whipped into a frenzy by calls for tribal solidarity. Some just viewed the snatching as another job; incredibly, they would return to the Gathenji house afterward, having helped to kill their benefactor, looking for more construction work.

Gathenji was given further details: that his father had been packed into the back of a covered Peugeot pickup for a drive into the countryside to the oathing center. That he’d preached to the women who accompanied him in the truck. That they’d been singing. And that the attackers had had to force open his mouth to pour the goat blood down his throat.

THE STORY WAS carried in Target, a newspaper published by the National Council of Churches of Kenya. The accompanying photographs included one of the pastor’s coffin as it was being carried to its grave, and a portrait of his bespectacled twenty-year-old son, Charles, his features rigid with fear and the weight of his new knowledge. Christian leaders mounted protests and visited Kenyatta, urging him to stop the oathing campaign. It ceased shortly afterward. The president had reportedly been unhappy with the evangelist’s slaying. It hadn’t been meant to happen, Gathenji thought. It had probably been intended as a beating—they’d inflict pain until he relented. They had misjudged their victim’s nature.

Gathenji expected the Presbyterian Church of East Africa would honor his father with a memorial. Instead, local church leaders balked at the perceived danger; Kenyatta’s security men were shadowing the family. Gathenji borrowed money for a tombstone. At the funeral, he found himself studying the faces of the mourners, wondering who had betrayed his father to the oath men. With his mother dead, his brother Henry dead, his father dead, and whatever trust he had in friends now an impossibility, he felt a deep and ineradicable sense of isolation.

He was not surprised that no inquest was conducted and no one was prosecuted. Everyone wanted the case forgotten. To dig too deeply into it would have implicated the nation’s legendary founder and the men he kept closest.

Though he prayed for the strength to forgive, he wasn’t sure he was capable of it. He was not his father, and the killers weren’t coming forward to ask his forgiveness, in any case.

Replaying their last exchange, he came to think that his father had been trying to warn him away from the quicksand of bitterness. Telling him to find a way to move on, because there was no way to right this particular evil. Telling him not to let it become a devouring obsession. Telling him not to waste his life.

No, he thought, he couldn’t forgive, but he couldn’t realistically expect justice, either. He would have to accept that the situation was hopeless and make peace with it.

With help from his extended family he transferred to a government-run boarding school near Mount Kenya. He felt safer there; he wouldn’t leave the compound for the whole term.

People still doubted he’d go far, as his education had been so erratic. No one in his immediate family had attended college. But the need to finish school had never felt more urgent. Quietly, he’d taken an oath of his own. Later, asked to explain his decision to pursue the law, he would never hesitate to point to his father’s murder and the subsequent inability to bring anyone to book. Along with a deep wariness, he had developed a preoccupation with justice. He thought that the law, properly wielded, might be a searchlight, an antidote to historical amnesia, a counterweight to arbitrary state power and the madness of the mob. For all the ways it could be corrupted, the law lived on the ideals of order and reason and discipline; these would be his plank against the undertow of despair. “I want to be rational,” he would say with characteristic terseness, trying to explain himself years later. “I think law assisted me.”

Government scholarships paid his way through three years at the University of Dar es Salaam, across the border in Tanzania, then in the throes of socialist fervor. It was a scorching, mosquito-infested place, where, between law classes, he endured malaria and ideological instruction in the wisdom of Lenin and Mao. At times, he had an exhilarating sense of a broader philosophical world than his British-based schooling had exposed him to, though he regarded revolutionary ideology, like alcohol, as being best consumed in measured doses. His classmates nicknamed him the “Chief Justice,” or “CJ,” a nod to the air of gravity and conservatism with which he carried himself. After another year at the Kenya School of Law, where he was apprenticed to a criminal defense lawyer, he joined the attorney general’s office as a prosecutor in 1975. It was a small office, and experience came fast.

The Kenyan courts were independent from the Crown but retained the trappings of Mother England. Lawyers appeared in black robes, and judges, called “Lords,” most of them still English, wore powdered wigs. In one of his first High Court cases, he prosecuted a farmhand who had strangled a baby. He went at it with vigor, arguing that the man should be hanged. His anger and disgust were so obvious that the judge cautioned him to moderate his tone. A finding of insanity won the defendant a reprieve. Such outcomes rankled the zealous young prosecutor. So much seemed to ride on each case; he internalized the defeats. It was not long before he understood the importance of a more clinical approach. He would be seeing death every day, after all. Domestic homicides, bar-brawl homicides, slum homicides; greed-motivated murder, lust murder, stupid, logic-defying murder; bludgeonings, stabbings, shootings.

During those years, Gathenji haunted the Nairobi Law Courts. One of the fixtures there was Joseph Gatuguta, who had been a member of parliament at the time of Samuel Gathenji’s death and was widely believed to have organized the oathing in the Kikuyu region. He had been voted out of office and was now a lawyer in private practice. Gathenji encountered him constantly in courtrooms and in corridors. It was unavoidable. Sometimes they’d be on opposite sides of the same case. Their exchanges were formal and tight. Gathenji had determined to bite back his bitterness and anger, knowing they might consume him. There was nothing to be gained by a confrontation. He was young and relatively powerless, recently married, with two young sons, plus five siblings who depended on him. He was just beginning to build a career and establish a foothold in the country’s growing middle class. Gatuguta’s manner seemed to suggest that he was punishing himself. In Gathenji’s presence, he looked like a man in torment. Gatuguta knew who the young lawyer was, of course. As if to confirm their connection, he would address him as “Kijana wa Gathenji.” Son of Gathenji.

THIS WAS STILL Kenyatta’s country, a prosperous and relatively stable land whose capital, with its bright bougainvillea-lined corridors, was known as the “City in the Sun.” The president had embraced capitalism-friendly policies and had enlisted the skills of Europeans and urged them to stay. For all that, his one-party state adumbrated horrors to come, from corruption to ethnic chauvinism to the assassination of political rivals. The so-called Kenyatta royal family grew wealthy smuggling coffee, jewels, and poached ivory (even as hunters eviscerated the nation’s elephant population). The ruling family was untouchable, a fact Father John Kaiser witnessed firsthand one day when he came across a group of elephant poachers on the savanna and asked a game ranger if he planned to take action. The ranger explained that they were connected to mzee Kenyatta: certain people he could not arrest.

THE MAN KENYATTA appointed vice president in 1967, Daniel arap Moi, belonged to the small, pastoralist Kalenjin from the far hills of the Rift Valley, and was thus deemed peripheral to the Kikuyu-Luo rivalry. He was lanky and gravelly-voiced, a former herder and schoolteacher, a stolid, awkward teetotaler with a reputation for servility. He seemed little threat to the interests of the Kikuyu elite, who derided him as “the passing cloud,” a marionette who could be counted on to serve their interests and then discarded. This was a miscalculation in the extreme. He assumed power on Kenyatta’s death, in August 1978, outmaneuvering Kikuyu plots to thwart his ascent.

Moi made it a point to advertise his Sunday attendance at religious services. For a time, the country’s churches embraced this pious mask at face value. “Indeed, we regarded him as a great Christian prince, ‘Our Beloved President,’” John Kaiser would write in a memoir years later.

Moi liked to call himself the “Professor of Politics” and identified his philosophy as “Nyayo,” or footsteps—suggesting he was following the path blazed by Kenyatta. Yet he lacked much of what had made Kenyatta effective: personal charisma and oratorical flourish, the mythic gravitas of an independence hero who’d endured exile and a nine-year prison term. Nor did he have the luck, as Kenyatta had had, of a good economy to help obscure his greed.

Crucially, Moi also lacked the backing of a powerful ethnic group. He would embody, and skillfully exploit, free-floating anxieties about the dominance of the populous, advanced, urbanized Kikuyu, anxieties that had been amplified by their rush into the Rift Valley under Kenyatta. Moi rewarded fellow Kalenjins with top posts in his cabinet, the military, the banks, and the civil service, while publicly condemning tribalism as the “cancer that threatens to eat out the very fabric of our nation.” Despite his rhetoric of a unified Kenya, division was the spine of Moi’s rule. The Kikuyu and the Luo together comprised more than a third of the nation’s population; their numbers would overwhelm him should they ever unite in opposition. A fractious and tribally minded country was one he could rule indefinitely.

GATHENJI ENTERED PRIVATE practice in 1980. On his wall hung a photograph of Moi standing with Kenyatta. He represented clients who had been swept up in government raids in the northeast province bordering Somalia, which was under emergency rule amid threats of succession and widespread violence from militias and bandits, called shifta. Suspects were hauled in on gun-running charges on flimsy evidence. Residents were required to be in their homes between the curfew hours of 6:00 P.M. and 6:00 A.M.; someone caught outdoors fifteen minutes later would be charged. Gathenji argued for a broad interpretation of the definition of home: If you lived in a hut or a tent and stepped into the bush to relieve yourself, you were still on home ground. Few lawyers took these cases. He risked the perception that he was collaborating with the government’s enemies.

The unhappiness with Moi already ran deep, and talk of coups was everywhere. Gathenji was not entirely surprised when, one morning in August 1982, he turned on the radio and heard that the government had been overthrown. He was living with his wife and two young sons in a Nairobi suburb. Disgruntled junior officers of the Kenya Air Force—mostly Luos—had seized the airports, the post office, and the Voice of Kenya radio station. The country’s new masters announced that existing codes of law had been suspended, effective immediately. Gathenji said to his wife, “Did you hear what happened? I no longer have a job.” It was impossible to gauge the seriousness of the danger. The continent had become an ever-changing map of violent and quickly deposed strongmen.

In the pandemonium, rioters looted Nairobi, inflicting a disproportionate toll on businesses and homes owned by Asians, who occupied the merchant class and were widely resented as outsiders. Scores, perhaps hundreds, of Asian girls were raped. Moi’s loyalists swarmed the city, fanned across the rooftops, and gunned down suspected insurgents and looters. The coup was crushed, and Moi was restored to power almost immediately.

Gathenji drove into town days later to inspect his office. He’d heard a rumor that the capital was safe, but it took only a cursory glance to sense it had been a false one. Bodies were still slumped inside bullet-riddled cars along the road. Televisions were lined up on the sidewalks, and broken glass glinted on the pavement. Every rooftop seemed to bristle with rifles. Soldiers were jittery. They ordered Gathenji to step out of his car and place his hands above his head and his ID card in his mouth. One soldier insisted that Gathenji had stolen his car, and he demanded that he prove otherwise by furnishing registration papers. Gathenji didn’t have the papers on him. For a moment, he thought, This is where I am shot. On Uhuru Highway, heading back home, he drove frighteningly close to a camouflaged tank, planted in the road, before he realized what it was. He turned the wheel hard and found another way home.

Soon after the abortive takeover, when the courthouses reopened, Gathenji arrived in court and found the dock crowded with defendants, some of them wildlife rangers and civil service workers, who had been charged with celebrating the coup. He watched a few plead guilty and receive jail sentences; in an atmosphere still so highly charged, no judge would leave them unpunished. Gathenji gave the others some advice: Enter not-guilty pleas and wait until the temperature abates. It proved a solid hunch: The cases were soon dismissed. The president wanted to discourage the impression, it appeared, that any of his subjects had reason to celebrate his ouster.

Meanwhile, in Kisiiland, an obscure middle-aged missionary named John Kaiser was trying to assess the country’s trajectory. “The coup attempt was a terrible shock to our Asian community & many of them are leaving the country,” Kaiser wrote in a letter to Minnesota. “The result will be great harm to the economy of Kenya but you sure couldn’t tell the average African that. On the day of the coup attempt I knew all policemen, G. wardens, etc would be in their barracks and huddled around radios so I took the opportunity to picky picky into Masailand a few miles and harvest a nice fat young w. hog.” His humor veered into a rare, dark register. “We had to do without such delicacies for many months due to the pressure of the special anti-poaching unit in the Kilgoris area, so we were grateful to the coup leaders & look forward to many more.” By the end of the month, Kaiser was sensing the atmosphere had changed permanently. “Things are quiet,” he wrote, but added, “I’m afraid the country won’t have the same easy peaceful aspect from now on.”

5

THE DICTATOR

IT WAS A prescient assessment. The violence, and the fears it unleashed, proved useful to Moi, who justified his tightening grip as a safeguard against further anarchy. Paranoia became entrenched as national policy. Because it was dependent on Western aid and tourism, Kenya required the barest simulacrum of democracy and the rule of law. This did not prevent him from outlawing opposition parties and expanding the secret police. He eviscerated judicial independence at a stroke, pushing through the parliament a law giving him the power to sack any judge at his whim. The entire justice system fell into his grip; no one would be prosecuted, or spared prosecution, if he decreed otherwise. The courts, stacked thick with his stooges, were spiraling into a morass of corruption so universal that there was little effort to hide it. Three out of four judges, by Gathenji’s estimate, expected bribes; clients expected to buy their way out of trouble. More than once, he found himself preparing a case meticulously, building it airtight, only to lose on the flimsiest pretext. Everyone knew: Somewhere, money had changed hands.

To Gathenji, a portal into Moi’s nature—a suggestion of his tactics and how he would employ them—came in 1983 when he destroyed his ambitious attorney general, Charles Njonjo. Moi accused him of being a traitor in thrall to a treacherous foreign power attempting to overthrow the government of Kenya, stripped him of his power, and consigned him to political limbo. He was allowed to live, technically a free man, but as a nonentity. It was a lesson to potential rivals not to climb too high.

Gathenji could sense the president losing his mind. He watched as Moi systematically purged Kikuyus from positions of power. Journalists who asked questions found themselves in lockup. In one case that particularly infuriated Gathenji, he represented a woman who had been charged with possessing Beyond, an Anglican church magazine banned for its critical remarks about the regime. It had been found in her coffee table, and she was taken into custody with her newborn baby in her arms. He argued she hadn’t known the magazine was there; people were known to work out grudges by planting a banned publication on an enemy’s premises. The case was dismissed. Police had lost their interest in it anyway; it had been enough to scare the woman. That was the dynamic of dictatorship. To create an all-encompassing chill, you needed to lock up only a few.

“Foreign devils” and Marxists, said to be plotting constantly against the nation, became the convenient pretext Moi trundled out to crush enemies. “Bearded people”—intellectuals—were deemed suspect in their loyalties. Members of Amnesty International became “agents of imperialists” after they criticized his human rights record. He employed a colonial law called the Public Order Act, which forbade nine or more Kenyans from assembling without a government permit. As his search for enemies intensified, Moi dispatched people to “water rooms” under a Nairobi high rise called Nyayo House, where they were forced to stand in excrement-filled water for days. Moi expanded police detention powers so that those accused of capital crimes, such as sedition, could be held for two weeks without a hearing, ample time for torture squads to extract confessions. Scores of such prisoners were hauled before judges who accepted their guilty pleas and handed out four- or five-year sentences.

Moi carried a silver-inlaid ivory mace and wore a rosebud in the lapel of his Saville Row suits. With his claim on legitimate authority so flimsy, he mastered the tactics of large-scale bribery and intimidation. He made a practice of wholesale land stealing, using vast tracts of seized public land as payment to ministers and military officers; this was meant as a hedge against another attempted coup. He handed out stacks of cash to State House visitors and to the masses he met across the country during rounds in his blue open-topped Mercedes.

“I would like ministers, assistant ministers, and others to sing like a parrot after me,” Moi said. “That is how we can progress.” His subordinates vied to outdo one another in cringing sycophancy, their speeches hailing his mastery of foreign and domestic affairs, his deep compassion—yes, one declared, even the fish of the sea bowed before the Father of the Country. Parliament passed a law declaring that only Moi could possess the title of president, in any realm. Ordinary souls who ran charities and businesses would have to content themselves with the title of chairman. To his worshipers, he was “the Giraffe,” an admiring nod both to his height and farsightedness, or “the Glorious.”

“Kenya is a one-man state, and that man is the president,” Smith Hempstone, the former U.S. ambassador to Kenya, wrote in his memoir, Rogue Ambassador.

Paranoid Moi was, but also skilled at shuffling and reshuffling his underlings to keep them forever off balance. “You know, a balloon is a very small thing. But I can pump it up to such an extent that it will be big and look very important,” he said. “All you need to make it small again is to prick it with a needle.” Under his command were more than one hundred state-owned companies, or parastatals, that did business only with “patriotic” firms; the slightest dissent meant one’s contracts evaporated. The British system of pith-helmeted chiefs was gone, supplanted by a vast network of chiefs and subchiefs that provided Moi with intelligence and control all the way to the village level.

The Soviet foothold in Angola and Ethiopia seemed, to American eyes, a harbinger of continental Communist designs, and Moi reaped massive U.S. aid by positioning his country as “a pro-Western, free-market island of stability in the midst of a roiling sea of Marxist chaos,” Hempstone would write. “Moi’s one-party kleptocracy might not be a particularly pretty boat, but it was not to be rocked.”

Here and there, Kenyan clergymen raised their voices, with harsh results. After a Presbyterian minister named Timothy Njoya called for “dissidents, malcontents, critics, fugitives and anyone with a grievance” to speak out, Moi swiftly summoned Protestant and Catholic leaders to State House to warn against such “subversive” sermons. Njoya was defrocked but won back his position. During marches for constitutional reform, he endured bayonet-wielding soldiers, beatings, tear gas, and jail. Once, attackers doused his parish house with gasoline and set it ablaze. He seemed to feel that it would have been worse if the president had not been a churchgoing man. “Moi’s Christianity is our protection,” he said. “That’s our secret as pastors in Kenya.”

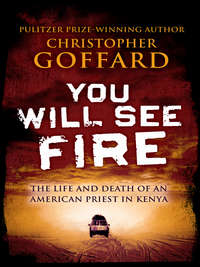

Kenyan president Daniel arap Moi became one of Africa’s longest-reigning dictators. Photograph by Francine Orr. Copyright 2003, Los Angeles Times. Reprinted with permission.

Under Moi, brutality walked hand in hand with farce. When Ngugi wa Thiong’o published the novel Matigari in 1986, Moi ordered the arrest of its fictional hero after receiving reports that “peasants in Central Kenya were talking about a man called Matigari who was going round the country demanding truth and justice,” Ngugi would write. The dictator was forced to settle for confiscating the books.

After the National Council of Churches, a mainstream Protestant body, objected to the abolition of secret balloting, Moi accused an Oregon-based missionary group, which had been digging water wells in northwestern Kenya, of plotting against the government. Police confiscated pellet guns the missionaries used to fend off snakes, a cache of uniforms sewn for local students, and shortwave radios used to communicate in a remote region without telephone service. These, by the state’s account, were armaments, military uniforms, and sophisticated communications equipment, all intended to “cause chaos,” Moi said, adding this complaint: “Why don’t they use their resources to build churches and bring in related things—like Bibles?” He later deported seven American missionaries accused of “sabotage and destabilization.” The evidence: a sloppily fabricated letter revealing their scheme to overthrow his government in collaboration with the Ku Klux Klan.

Once, during a spat with Hempstone, Moi sent police to seize a package of school textbooks—they included Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn—that the U.S. ambassador had donated to a poor rural school. Moi’s men denounced the books as “sinister” and said they were designed to “pollute the minds of peace-loving wanachi [masses].”

The president’s dour countenance glared from the walls of every shop on every block; his name was plastered on uncountable roads and bridges, stadiums, and schools. He put his profile on coins and a full-frontal close-up on bills. His prosaic daily pronouncements inaugurated the evening news on state-run television: “His Excellency the President Daniel arap Moi proclaimed …” He invented Moi Day, a holiday on which his people could express gratitude for his leadership. To celebrate his first decade in power, he commissioned an Italian marble statue in downtown Nairobi’s Uhuru Park that depicted his enormous hand, clenched around his ivory mace, rising triumphantly out of Mount Kenya toward the sky. (Considering the mountain was both the nation’s namesake and the Kikuyus’ most sacred site, no less than the dwelling place of God, the monument carried a certain nasty symbolism.)