You Will See Fire

By the late 1980s, criticism was growing louder, even from within the superpower that was sponsoring him. Edward Kennedy publicly urged Moi to “pull back from the darkness of torture and repression and return to the bright sunlight of freedom, tolerance and the rule of law.”

Faced with such talk, Moi had a typical response: Look at my neighbors. His record, he pointed out again and again, was much better than that of Ethiopia, Sudan, and Uganda. Why should Kenyans expect democracy? he asked, invoking the West’s tormented history of race relations. The country had only gained independence in 1963. After breaking from the Crown, he argued, it had taken the United States two hundred years to achieve democracy.

Moi avoided interviews and wrapped himself in enigmatic silence. His authorized biography portrays him as a man who loved his Bible and simple country living, a ruler whose one-party state represented a bulwark against civil war in a cobbled-together nation of forty-two tribes and thirteen languages.

A more plausible glimpse of his psyche can be found in Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s novel Wizard of the Crow, which proceeds from the moral premise that only fantasy can capture the absurd nightmare that is existence under a Moi-like dictatorship. It describes a megalomaniacal ruler who has been “on the throne so long that even he could not remember when his reign began,” and who yearns to erect a tower that stretches to heaven, the better to call on God. At the core of this personality is a corrosive, all-consuming anger, an “insatiable desire for humiliating the already fallen.” Having cringed beneath endless abuse during his rise to power, he now demands endless groveling from others. He foments pandemonium and then postures as “a Solomonic prince of peace.”

JOHN KAISER WAS beginning to glimpe the scope of Moi’s cruelty as early as 1986 and 1987. He was living in Nyangusu, on the border between the dense farming area of the Kisii and the sparsely populated vastness of Masailand. For years, he’d watched the groups skirmish over cattle and boundary lines, staging elaborate—and mostly harmless—face-offs that Kaiser viewed “more as recreation than a serious war.” He’d watched as combatants assembled on either side of the mission football field, hurled menacing insults at one another through the night, and unleashed high arrow volleys that rarely proved fatal. If killing had truly been the aim, Kaiser reasoned, they would have charged with their spears.

But what he witnessed now, in the mid-1980s, had a different feel entirely. Thousands of Kisii peasant farmers were streaming through the countryside with their belongings. Political bosses had ferried in gangs of Masai warriors to burn their homes and destroy their schools. Informants told Kaiser the attackers belonged to the private mercenary army of William ole Ntimama, then the regime’s most powerful Masai. Investigating the refugees’ claims, Kaiser witnessed government paramilitaries and police evicting farmers from their land en masse as the police stood by passively, intervening only when the Kisii fought back.

In early 1988, Kaiser took the news to his bishop, Tiberius Mugendi, an aging Kenyan whom he regarded as a spiritual father. Mugendi had assumed the violence reflected “the usual fights over cattle rustling” and dismissed the possibility of government involvement: “Impossible!” That would mean the sanction of Moi, and Moi was the country’s benevolent father.

Little would be written about the mid-1980s clashes, and Kaiser would later castigate himself for his passivity. Concerning the violence, he believed himself “the best informed Christian” and “the best placed to take effective action.” He shared his findings with superiors, as well as with the Church’s Justice and Peace branch, but regretted that he didn’t go further. He could have contacted Western embassies, human-rights groups, or Bishop Raphael Ndingi of Nakuru, Kenya’s most outspoken Catholic human rights champion. “But I did none of these things. Like Pontius Pilate I washed my hands on the grounds that I had plenty of other work in a busy parish,” Kaiser would write. “In so doing I stored up more fuel for a long hot purgatory.”

Through the 1980s, his life remained a largely anonymous one of baptisms and herculean building projects, of confessions and sick calls, of rugged trips on his Honda motorcycle down crenellated laterite roads, across mapless valleys and hills. Fever and malaria, dysentery and pneumonia and rabies sent him again and again bearing bodies to ancestral burial plots deep in the bush, praying people into the earth as the clustered women sent up their stylized wailing and the men stood around the grave with spears and pangas, their faces blank and hard. He built tractors and oxcarts, planted crops, demonstrated Western methods of fertilizing. He bought second- and thirdhand trucks, not just to save money but because buying new ones would have enriched government men. He made a wooden wheelchair for a crippled boy and bought the family a donkey to pull it. He took confession in the shade of eucalyptus trees and threw up churches across the countryside, quick, crude structures of red earth and river-bottom sand. He earned a nickname, “Kifaru wa Maskini”: Rhino for the Poor.

As often as possible, he vanished into the bush and returned with meat to distribute. The landscape of his missives teemed with animal carcasses, and he took a raconteur’s pleasure in recounting close calls. One day near dark, walking along the edge of the woods, he heard “the grumbling of what I was sure were giant forest hogs in the bush,” he wrote in one letter. “I loaded up with 00 Buckshot, put some dirt on my face (something it’s not used to) & slipped into the bush as quietly as Hiawatha. I could hear the ‘pigs’ clearly & thought I would easily get one. But as I got deeper in the bush & closer to the grunting I detected a peculiar tone to their symphony & started getting apprehensive. When the grunting became growling the dirt on my face was being washed away by the sweat. I had come right into a pride of lions, at least 9 of them. One huge male stepped out from behind a bush about 15 yards away; he was very angry & nervous & his tail was whipping back & forth; by this time I was backing up full speed in reverse & they were all gentlemen enough to let me pass unmolested.”

At one point Minnesota friends supplied him with jacketed bullets, a tin of rifle powder, and an H & R single-shot .30-30 rifle with a mounted Redfield scope. This allowed him to strike an animal from eighty yards. Now, entering the bush, he carried this “lovely little gun” slung on his back, along with his twelve-gauge double-bore shotgun with double-ought buckshot in his hands “in case of something unexpected like a lion or bad buffalo.” Once, he tallied up a year’s worth of rifle kills:

“12 impala—about 150 pounds….

9 topi—350 lbs & over

8 oribi—40–50 lbs

6 grey duikers—30–40 lbs

2 Reedbucks—100 lbs

2 warthogs—120 lbs

1 waterbuck—300 lbs

That is 40 animals in a bit over a year which is not bad—about 3,560 pounds of meat after butchering.”

Another letter from the mid-1980s described the abiding exhilaration of missionary work. “I have just come back from a sick-call which I was lucky to sneak in just before dark & not get rained on,” he wrote. “The sick-call was for a young girl who is dying apparently having returned from hospital where the doctors have given her up. She is a very beautiful girl of 18 who received the Sacraments most beautifully and serenely. At such times I would not trade being a priest for any position.”

THEN THE SOVIET empire collapsed, and with it the West’s justification for reflexive support for Moi. In May 1990, soon after his arrival, Hempstone, the improbable U.S. ambassador—a blunt-spoken former editor of the conservative Washington Times who’d parlayed connections in the Bush administration into a diplomatic post—galvanized a weak and demoralized Kenyan opposition with a speech at the Rotary Club of Nairobi. From now on, he said, the United States would steer money to nations that “nourish democratic institutions, defend human rights, and practice multiparty politics.” The regime’s mouthpiece, the Kenya Times, answered his challenge with headlines like this: SHUT UP, MR. AMBASSADOR.

Dissidents took courage, even as the regime characterized the call for democratic pluralism as the latest thrust of white domination. The year was full of grim and portentous spectacles, including the murder of Robert Ouko, the country’s urbane foreign minister, who had been compiling documents on high-level corruption. He was discovered on a hill, shot twice through the head, his body charred, a .38 revolver lying nearby. Suicide, announced police. The president promised that “no stone would be left unturned” in finding answers. To demonstrate his commitment to the truth, he called in New Scotland Yard, which took four hundred depositions over four months and discovered that Ouko had been at odds with Nicholas Biwott, Moi’s widely feared right-hand man. The investigation also pointed to Hezekiah Oyugi, the secretary of internal security.

The head New Scotland Yard detective, John Troon, complained that he was not allowed to interview either of these two key suspects, who were briefly arrested and released for “lack of evidence.” Moi closed the investigation and refused to accept New Scotland Yard’s report unless Troon delivered it personally (a condition tough to meet, since Troon had already left the country). Moi appointed a commission of inquiry to take testimony, then dissolved it before it reached conclusions, sending the case back into the hands of the Kenyan police. By such methods, Moi could drag out an investigation forever. This would prove one of his signature moves. Memories would fade, and witnesses would vanish (within a few years after the killing, eleven people connected to the case, including Oyugi, would perish, some under strange circumstances).

The Ouko case would be etched in the national psyche as an illustration both of Moi’s ruthlessness and his wiliness. The U.S. ambassador, for his part, had no clear evidence of who had killed Ouko, or why, but “what did appear obvious was that the murderer was too highly placed and powerful to be apprehended,” Hempstone wrote.

It was a season of smoke and truncheons and proliferating dissent. Activists and lawyers launched a group called the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD). Moi rounded up dozens of opposition figures; police fired on protesters and raided an Anglican cathedral where they sought sanctuary. The country’s seventeen Roman Catholic bishops—representing Kenya’s largest Christian group—issued a pastoral letter denouncing the ruling party’s “unlimited authority,” and complained that “the least sign of dissent” was deemed subversion. Mild as this seemed, it represented relatively bold language for the cautious bishops. In late summer, a milk truck plowed into a car carrying an Anglican bishop named Alexander Muge, who had denounced corruption and land grabbing by unnamed regime potentates; a parliamentary commission ruled it “death by misadventure,” a verdict tough for many Kenyans to embrace. Moi’s labor minister had recently warned that Muge would “see fire and may not leave alive” if he strayed into his district.

Though Kenya remained the largest recipient of U.S. assistance in sub-Saharan Africa—it had received $35 million the year before in economic aid and another $11 million in military aid—American congressional leaders now urged a freeze. With the Marxist menace dead, Moi’s carte blanche had been yanked.

One day, the phone rang on Charles Mbuthi Gathenji’s desk. The man on the other end was a reporter for the state-run television station. He wanted to know the lawyer’s views on a recent controversy: The new chairman of the Kenyan Law Society, Paul Muite, was using his platform to denounce the president and call for reforms. Pro-government lawyers, for their part, had decried such “meddling” in politics.

Where did Mr. Gathenji stand?

He saw nothing wrong with Muite’s remarks, he said; they reflected the sentiments of a good portion of Kenya’s legal community, and nobody called it political meddling when lawyers praised Moi.

Gathenji hung up. Soon, he learned that his statement had made the nightly news. He realized that he’d been incautious. He knew this even before the letter came in the mail demanding payment for back taxes he supposedly owed, equivalent to more than six thousand U.S. dollars. He had ten days to pay, or his home would be seized. He knew other lawyers were getting similar letters. He called his accountant. Numbers were examined. He did owe money—about a fourth of the figure claimed. He paid up. He didn’t want to give the government any excuse to harass him.

Now he understood the reason for the reporter’s call. As dissent grew bolder, Moi wanted to know who was on his side.

MEANWHILE, IN KISIILAND, Kaiser, already in his late fifties, was feeling the effects of age. He described himself as “the chap who never got malaria for 20 years”—he’d been able to banish the early symptoms with a course of chloroquine—but in early 1990 the disease sent him to the hospital for a five-day course of quinine, incapacitated him completely for three days afterward, and stripped twenty pounds from his frame. “Malaria is no longer a minor nuisance & from now on wherever I go the net goes along,” he wrote. Soon he was racing around on his Honda motorbike—a piki-piki in Swahili—joking, “I use a motorcycle every day but at a sedate & dignified pace such as befits my age & position.” There had been some bad spills in recent years. Once, as he rode after dark, the blinding light from an oncoming bus sent him off the tarmac, and a sharp edge of asphalt opened a big gash in his shin. Another time, doing forty as he headed down a narrow gravel road to a sick call, he swerved to avoid a cow, breaking his collarbone and two ribs. Alone on the empty country road, he’d been forced to pull himself to his feet and find his way to the hospital without fainting from the pain.

The culture of corruption was making itself felt at every level. To repair his motorcycle meant paying a 200 percent bribe for the spare parts. The corrosion of the rule of law was increasingly painful and personal. That March, he learned that a friend named James Ongera had been working on his farm when three agents of the General Services Unit attacked him, for reasons that were unclear. His spine was broken, and his body was dragged to the Masai border and mutilated, apparently to convince the Kisii that the Masai had been responsible. The family brought suit against the three agents; the courts threw it out.

“There are almost daily murders in the Nyangusu area and the real culprits are the various government officials who use the army and police to drive out settlers in Masailand so that the land can then be grabbed and sold for huge profits,” Kaiser wrote in the summer of 1991. He added that his bishop, Tiberius Mugendi, now in his early seventies, “looks old & worn out and I suppose it is no wonder considering the chaos of his ministry.” Kaiser’s own energy was ebbing. Even a proud man had to concede the toll. A year would pass without a hunting excursion, apparently a record hiatus. “I have quite a bit of building to do in finishing up the convent & it poops me out in a hurry; in a few years I’ll have to find a rocking chair,” he wrote. Reminders of his mortality sometimes seemed to ambush him. Looking at himself, he glimpsed a reflection of his father, Arnold, who had died five years back. “I got a haircut a week ago & the guy had a mirror in front & another one in back & so I could see him trimming the back of my neck & I said, ‘Hey, that’s not John that’s Arnold Kaiser.’ Look at that grey hair & the wrinkles in the neck; it was a shock.”

An avid newspaper reader and BBC listener, he was closely following the unfolding political drama. International donors kept turning the screws on Moi’s increasingly desperate and beleaguered regime. The United States slashed nearly a quarter of its assistance, including fifteen million dollars in military help. In November 1991, an array of Western benefactors voted to suspend World Bank aid until Moi embraced democracy and curbed corruption.

Considering foreign aid comprised 30 percent of the national budget, this was no small blow. Days later, Moi hastily assembled party delegates at a Nairobi sports stadium and stunned them with an announcement. He would rescind Section 2A of the constitution, which had made Kenya a de jure one-party state nine years earlier.

He made it clear that the West was forcing his hand. “Tribal roots go much deeper than the shallow flower of democracy,” he would say. “That is something the West failed to understand. I’m not against multipartyism but I am unsure about the maturity of the country’s politics.”

What followed fulfilled his warning—or, as many understood it, his threat—that in an ethnically fractured nation, democracy would lead to bloodshed.

Facing ruin, he sought insurance in the usual playbook: the exacerbation of ethnic antipathies. To ensure party supremacy, militias descended on opposition strongholds, purging rival voters from areas where they were registered.

Village after village erupted in flames; within several years, more than 1,000 people would be killed and 300,000 displaced. Moi banned public rallies and sent helmeted agents plowing into defiant crowds on horseback and on foot, firing tear gas, swinging truncheons and pickax handles. By early 1992, even Kenya’s cautious Catholic bishops were uniting to accuse the government of complicity in the brutality. Regime hard-liners publicly urged the eviction of groups that had settled in the Rift Valley after independence. The Kikuyus were “foreigners” there, and the land they’d occupied for decades constituted madoadoa, or “black spots,” on the map: they needed to be erased.

6

THE CLASHES

AS VIOLENCE ROILED the countryside through the early 1990s, and as reports of the bloodletting reached Kaiser’s parish in increasing numbers, his rift with his elderly bishop, Tiberius Mugendi, grew wider. The two had been close; Kaiser regarded him as a “Spiritual Father.” Mugendi’s autocratic streak was deep: He bristled when subordinates challenged him. He would travel to the various parishes of his diocese to interrogate young catechists on matters of doctrine. They were to recite correct answers about the mysteries of the Host and the rosary; a sloppy answer might provoke a slap.

At one church meeting, Tom Keane, an Irish priest from the Mill Hill order, suggested this approach showed a lack of faith in the priests’ ability to teach the children. Other priests echoed the sentiment. Days later, Mugendi summoned Keane to his house, accused him of leading a rebellion against him, and ordered him out of his diocese immediately. Mugendi’s back was turned as he spoke, and Keane would remember, years later, the sight of the veins bulging on the enraged bishop’s neck.

Keane grasped the subtext: To criticize your bishop in public was to cause him to lose face. It was a display of Western effrontery. It was not to be done.

Kaiser, for his part, never absorbed the lesson. He criticized not only the bishop’s method of grilling confirmation candidates, but of promulgating doctrines, such as a three-part liturgy, that preceded Vatican II reforms. Kaiser also attacked the bishop’s judgment in appointing a headmistress to the local girls school whom Kaiser considered dishonest. As was his habit, he carefully and bluntly enumerated his reasons in a letter, with numbered points and subpoints. The headmistress was often absent from the school, he explained, had collected money without reporting it, and lingered provocatively around married men. “Let me ask you in all respect, my Father-in-Christ,” Kaiser wrote. “What qualities did you see in this woman or in her past record that you would recommend her as the H/M of a Christian School?”

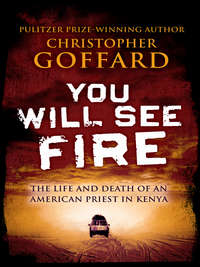

John Kaiser’s passport photo. One of the few American members of the London-based Mill Hill Missionaries society, he inveighed against what he saw as his order’s feckless response to state violence in Kenya. He would be past middle age himself by the time he began waging a public campaign against the Moi regime. Photograph courtesy of Francis Kaiser.

The dispute with his bishop ran deeper still. With villages erupting in a pandemonium of flame, arrows, and machetes, Kaiser questioned Mugendi’s refusal to take a forceful stand against what seemed clearer by the day: that the regime was exciting the Masai and Kisii to war. It was Kaiser’s insistence on doing so in public, before other churchmen—including young African priests—that Mugendi found intolerable. The American priest was breaching the deep-dyed cultural prohibition: An African bishop, like a president, was a paternal personage not to be challenged. “Here in Africa you never discuss the Father, much less criticize him in public,” Kaiser wrote.

Other priests warned Kaiser that his style was too confrontational. Ignoring pleas to back down, Kaiser wrote a letter, detailing his objections to Mugendi’s leadership and pointing out “the Catholic failure as regards Human Rights.”

Mugendi had had enough. He sent word to Kaiser’s superiors: Remove this priest from my diocese. Maurice McGill, the London-based superior general of the Mill Hill order, informed Kaiser that he should leave immediately, and invited him to spend some time at Mill Hill headquarters in London.

“I can hardly be appointed away from this place without an appointment to someplace else,” Kaiser wrote back. “Your invitation to visit Mill Hill is kind, but at this point I need clear orders and not an invitation. I will make no preparations for leaving here until I have heard from you and I would consider at least two weeks, but preferably four weeks, to be a reasonable time to finish up here and say goodbye to those I have lived with for nearly thirty years.” He said Mugendi had refused to speak to him that morning.

“I confess, Maurice, that I am deeply hurt by your action or rather lack of action as well as those Mill Hill superiors who have assisted you in withdrawing me. I would have thought that a minimum response from a superior would have been to ask the Bishop to put into writing the reasons for expelling me,” he continued. “I would not for any reason in the world contradict Bishop Mugendi except that I should think that not to do so would be disobedient to the clear teaching of the church. I will make a report of this affair for the priests here, the Kenya Hierarchy & the papal representative & also send you a copy.”

He distributed his letter widely within the Mill Hill organization and the African Church. He also reportedly sent a copy to the Vatican, a further humiliation for Mugendi. “I told him not to write the letter,” Keane recalled. “If he had something to say and do, he had to do it, regardless of whether it destroyed you or not. John would reprimand you and he wouldn’t care if you were hurt or not. He had also that cruel side in him, that justice was everything.” Keane said that Mugendi wept when he read the letter, and that it caused “tremendous hurt” between the mostly European Mill Hill members and the African Church. “They didn’t like the white man attacking the black bishop,” Keane said. “It wasn’t in John’s vocabulary to express regret.” It seemed no coincidence that people called him the “rhino priest.” This was the same John Kaiser, Keane recalled, whose answers to a psychological test administered by Mill Hill earned him a comparison to the animal said to charge friend and foe alike.

“My conscience is clear and I will not apologize for any of my statements or opinions,” Kaiser wrote to a friend that June. “I can always admit & lament the fact I am an undiplomatic clod, but for me that is not the point.”

Kaiser remained in Kisii as the elections approached. There was little doubt about the outcome. Violence was not Moi’s only tactic. The registration forms of illiterate voters could be invalidated by purposely misspelling their names; by these and other means, an estimated one million Kenyans were prevented from voting. The American ambassador was troubled by his nation’s decision not to boycott the election. Hempstone reasoned that such a boycott might have led to civil war, and yet “having put our imprimatur on a flawed electoral process, we seemed to be certifying that second-rate democracy was good enough for black people.”