The Levelling Sea: The Story of a Cornish Haven in the Age of Sail

This then is how history begins on the shores of the Lower Fal, with groups of beehive huts and shaggy men half attached to the world, who immersed themselves up to the neck in the freezing water and pressed songs of devotion from their chattering lips. They were holy sea-wanderers, peregrini, who in the name of Christ took to the open water in the post-Roman centuries, trusting less to the rigours of seamanship than to divine providence. The sea was their desert, a blank alternative to the troubled world, and retreating to it an enactment of the reckless example of St Anthony. But the waters of north-western Europe are a harsher place by far than the wastes of Egypt. How many perished, drowned or starved in the great flat-horizoned emptiness, we shall never know. In the Fal, salvation was a labyrinth of wooded creeks, tidal waterways that pushed up far into the hinterland. They left their names in a series of creek-side churches. The one here is St Anthony’s – the dedication honouring not the father of Christian monasticism, but the Cornish royal martyr, Entenius.

I work the mooring-chain over the samson post and watch it splash into the water. The weight of the chain as it sinks tugs the mooring buoy away from the boat. It is always a moment of anxiety, the severing of attachment. At the same time, Liberty’s bows are caught by the wind and blown further from the retreating buoy, down towards the shore. I jump inboard, jab the engine into gear, and head out of the river.

It is a bright day. A brisk westerly is driving gun-puffs of cloud across a clear sky. The water is flecked white, with short wind-turned seas that set up a barrelling motion in the boat. I lean back against the tiller. I can feel it in the small of my back. I can correct the lurch of the bows with the slightest movement. The village looks different from the water; all these years here and I’m still surprised by that: how seeing the land from the sea transforms it so completely.

Beyond St Mawes Castle, the estuary opens out, running several miles inland. I can see distant woods and fields and a few dot-clusters of white houses. Between them stretches the wide basin of the Carrick Roads, agreed by all who have written about it for hundreds of years to be one of the finest natural harbours in the world. I bring Liberty in past the town of Falmouth. The early sun lights up the town’s terraces, each one following its own contour-line along the slopes, a stadium crowd of a thousand windows. Against the outer arm of the docks lies a rusting stone-barge named Charlie Rock. Towering over it is a Monrovia-registered tanker waiting for repairs. High up on the rail, a tiny figure raises its hand to wave down at me. As I pass in under the stern, the dock opens out. So close to the houses, the ships look out of scale.

Until as late as the seventeenth century, there was no town here. There was nothing – no docks, no quays. Where the wharves are were shingle beaches and mudflats. A sandbar enclosed a swampy lagoon where the National Maritime Museum Cornwall now stands. The slopes above the low cliff were open country, copsed and dotted with furze. The town centre itself was a bog. (It is still known as ‘the Moor’, a place where swampy land meets the tide.)

Yet within a century and a half, Falmouth was one of the great ports of the fast-expanding world – a global thoroughfare of war-news and innovation, whispered espionage and gold bullion, its quayside crowded with footsore explorers, high-worded gospellers bound for the New World. The view from the wharves was a pitch-pine, hempen jungle of yards and sheets, masts and ratlines. The decks were so numerous, it was said, that you could walk from one side of the harbour to the other on them.

The steep arc of Falmouth’s growth reflects that of the era of sail, those ship-driven centuries that followed the Middle Ages. From the periphery of Europe, England emerged as a maritime power with such suddenness that it surprised her own people as much as it did her enemies. In the far south-west of the British Isles, Falmouth sprang from its bog with the same brash assurance. The Reformation prompted technical, political and cosmological changes that revolutionised mobility and fostered the restless urge to seek far-off lands. Falmouth itself was like a colony, an empty shoreline without a past, where the rootless and the hopeful could settle as equals.

Until that time, the Fal estuary had three ports. Each lay at the top of a long, tidal reach. Any settlement further downstream attracted the marauders who peopled the open seas and liked to burn the places they visited. Of the three, the most exposed was Penryn, a couple of miles up river from the site of Falmouth, where a chain could be stretched across the creek to repel incomers.

It is approaching high water when, later that day, I round the last bend in the Penryn river and see the ancient coinage town spread out over two valleys. Weekend yachts, day trawlers, houseboats and punts bob at the fringes of the creek. Alongside them lie semi-submerged hulks and wrecks, and the project-hulls of would be ocean-crossers, part-completed or long abandoned. I leave Liberty at Exchequer Quay and in sea-boots go up to the main road, standing to wait for the beep-beep-beep of the pedestrian lights before crossing. I follow the Antre river through the lower town and with the sun low find myself standing in the middle of an empty municipal field. The grass has just been cut. The trimmings lie in stripes at my feet, matted by the morning’s rain.

In the thirteenth century the Bishop of Exeter was visited in a dream by Thomas à Becket. Come to this place, he was told, to the marsh known as Polthesow, Cornish for ‘arrow-pool’, so named because hunted beasts would flee into its waters and disappear. Build an altar there and in that place ‘marvellous things’ shall be seen. The bishop drained the swamp and raised Glasney church based on his cathedral at Exeter and a full two-thirds of its size. It helped that the land at Penryn, its woods and pastures, for some way inland and for miles south along the shore towards the open sea, belonged to the diocese of Exeter, as did all the money-spinning rights of the coast – the fundus, oysterage, shrim-page and right of wreck.

A college was established, and a constitution drawn up, a wise and prudent document that proposed a presiding council of ‘13 discreet persons of the more substantial sort’. Thereafter at night, and ‘testified by the neighbours’, a heavenly light was often seen at Glasney glowing high above the heads of the holy men of the college gathered to praise the name of God. Marvellous things indeed.

Glasney College was soon one of the largest ecclesiastical centres of Cornwall. As the English state pressed westwards, on the tide of its own language, the college became a great promoter of Cornish. Around it, the port of Penryn prospered. Tin and stone were loaded on its strand. Hogsheads of salted pilchard left for the Continent. The fortified walls of the college offered protection from the sea, as did the barrage of stakes and stone and chain put across the river.

Through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, as sea trade increased around the coast, and as the coastal peoples of Atlantic Europe became more restless, so Penryn grew into one of the busiest ports in Cornwall. It was a frequent point of refuge. In 1506 King Philip and Queen Juana of Castile sheltered there for several weeks: ‘We are in a very wild place,’ wrote the nervous Venetian ambassador with them, ‘in the midst of a most barbarous race.’ Yet even in the Middle Ages, the sea had produced a cosmopolitan settlement. In 1327, half of Penryn’s population was described as ‘foreign’, Breton for the most part. As a language, English was the third or fourth most used. The college and the port complemented each other perfectly – ships coming to the Fal for shelter were drawn to Glasney, while their victualling needs produced a thriving commercial centre.

Glasney College.

But in time something of the worldly success of Penryn appeared to seep into Glasney College’s inner rooms. By the sixteenth century its officials were being described as ‘men of great pleasures, more like temporal men than spiritual’. The provost had little time for his ministry, preferring to ‘drink and joust’. Henry VIII’s Star Chamber was told how he ‘doth slay and kill with his spaniels, some days two sheep, some days three and divers times five in a day’. The college’s shoreside position, which had helped it to grow, now counted against it: ‘By reason of the open standynge of the same on the sea,’ gloated the Crown Commissioners shortly after Henry VIII’s death, ‘by tempest of weather felle into suche decaye.’

Yet it was Henry and not the weather that was to blame. Glasney College survived the dissolution of the monasteries, but was prey a few years later to the same covetous forces. Lead was peeled from its vaulted roofs and shipped to the Isles of Scilly to use in fortifications. Piece by piece the buildings were broken up. The bells were sold off. The stone was removed. For generations, vestments and treasures had been bequeathed to the college by wealthy men hoping for prayers in perpetuity. Now copes of green and crimson velvet were bundled up and taken off, as were bolts of cloth-of-gold, albs and chasubles, six altar-cloths of black, gold, green, blue and red velvet, and one of ivory satin, embroidered with images of roses and Our Lady, a bell with a handle of gold and red silk, breviaries, tabernacles and missals, and a piece of paper painted with the five wounds of the Saviour.

Standing alone in that playing field, I look around for traces of the college buildings. A panel-board shows the points at which archaeologists have recently conducted a series of digs. The dotted lines of their trenches are set against a plan of the church, and I am struck by its great size. Glancing away from the board, I picture the nave and aisles peopled by tiny figures, raising their heads and whispering – the grateful storm-survivors, passengers and merchants from the Low Countries, from France and Spain and Portugal.

Glasney was a part of that network of ports and havens and anchorages which for thousands of years had been not so much on the land-fringes of European countries, as on the edge of a loose nation linked by the sea. As they grew, sovereign states superseded many of those maritime links. Of centuries of ship-voyages, little evidence remains. Glasney’s archaeological digs turned up floors and tiles and fragments of worked stone. But the digs themselves have now been covered up, the portable finds removed, and there is nothing on this late summer day, not a bump or hollow or mound, to break the green of the empty acre.

Afternoon is sliding into evening. I return to Liberty and head out into the river. The tide has turned, and with it the moored boats have swung round to face the ebb. Somewhere here – between the wharves and warehouses to starboard, the woods to port – stretched the barrier that had protected Penryn and Glasney. It was the chain, and the narrow approach to Penryn, that enabled its rise during the Middle Ages, but it was the chain too, the closing out of the sea, that helped shut Penryn off from the bold and expansive age that was coming.

CHAPTER 3

One day a few weeks later, I row out to Liberty, fold up the cover and pump the bilges. The summer yachts have thinned out, laid up in the sheltered corners of the creeks. The shoreside oaks are still green, but something tired now shows in their foliage. A few hundred yards to the south, the Victorian facade of Place Manor rises from its sweep of lawn and gravelled drive. Almost completely hidden behind it is the much older church of St Anthony’s, its tower just clearing the manor’s roof like the mast of a sunken ship.

I drop the mooring and head out towards St Mawes Castle. From the far headland rises Pendennis Castle, and the two stand guard over the estuary’s approaches. When the religious community around St Anthony’s church was dissolved during the Reformation, the buildings were pulled down and the stone barged across the harbour to build St Mawes Castle. With a neat circularity, the castle had been commissioned to oppose the threat of papal retribution that followed the Reformation and the Dissolution.

In Falmouth, I moor up at the pontoon and walk through the town, over the railway, through a just-ploughed field to the hilltop church of St Budock. According to the boast on the service board, the church was founded in AD 473–1,000 years before the first buildings of Falmouth appeared above the strand. Budoc himself was one of the greatest of the sea-soaked saints of the Celtic Church. Venerated in Ireland, Wales and Cornwall, his story was carried between them, embellished by a thousand tellings. On Brittany’s hazardous shoreline, he has been called ‘le patron de ces côtes’ and in the miracles of his life, you can sense the particular licence of maritime myth: an adventure from the start, beginning in the middle of the English Channel, where Budoc was born in a bobbing barrel. Shaped by the winds, his earthly mission left him here for several years, above the Fal estuary, with his small group of monks, before he again took to the Channel, floating to Brittany in a stone coffin.

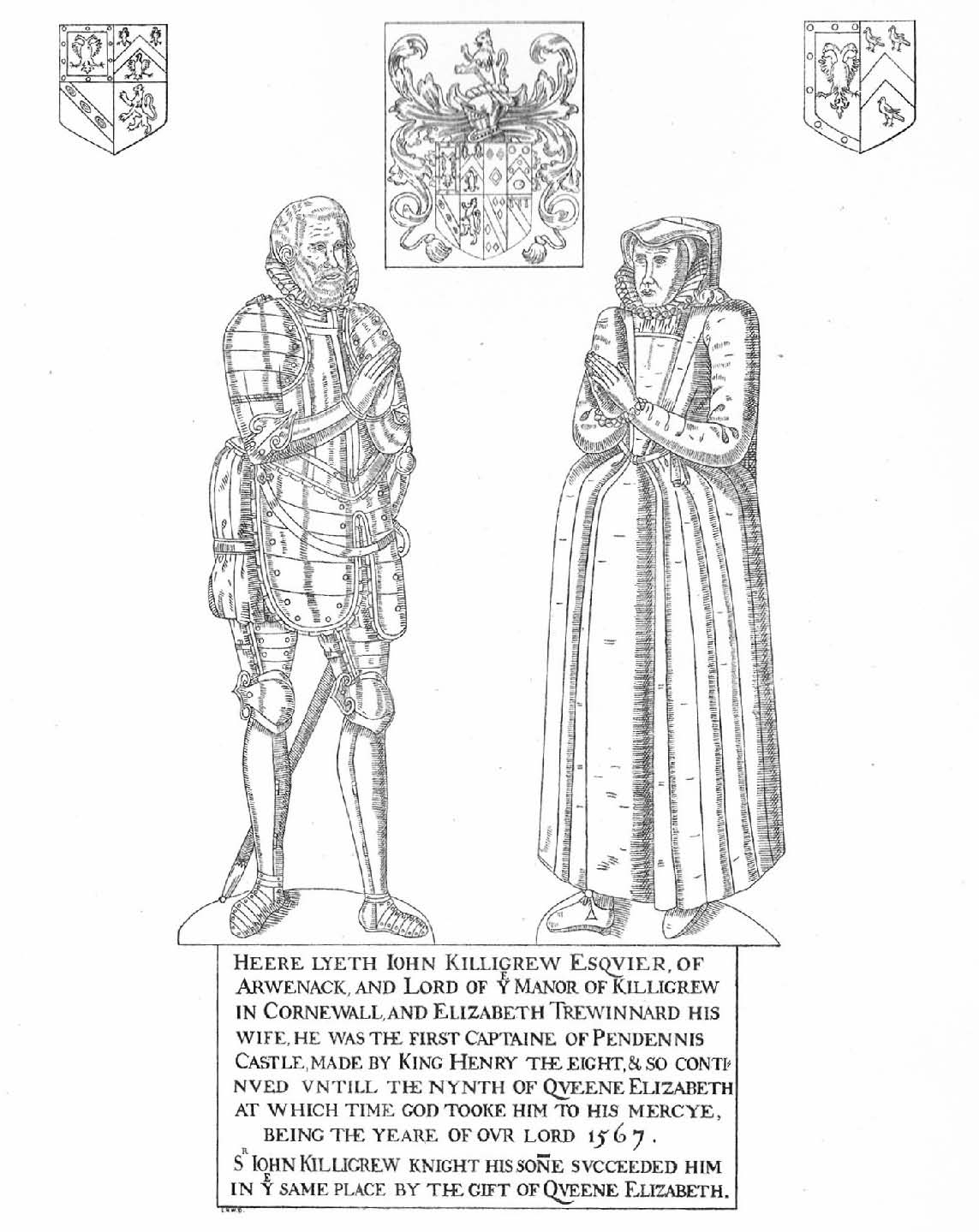

The church interior is damp and dark. Morning light falls through the high altar window, flashing on and off as clouds slide across the sun. A harvest tableau stands in a niche – bread rolls and a vase of poppies and cornflowers. Kneeling in front of the altar rail, I take the edge of the runner and roll it back beneath the chancel, revealing a grid of terracotta tiles. In the centre, set into stone, glints the panel I am looking for:

HERE LYETH IOHN KILLIGREW ESQVIER, OF ARWENACK …

AND ELIZABETH TREWINNARD HIS WIFE … GOD TOOK

HIM TO HIS MERCY THE YEARE OF OUR LORD 1567 …

Above the inscription, mottled with age, lie the couple’s brass images. I bend to examine them more closely. No trace of human softness crosses their faces, none of the flamboyance of the later Elizabethans. They are standing in prayer. Framed by a wimple, Elizabeth Killigrew’s expression is stern and manly. John Killigrew’s hair and beard are cropped short and he is dressed in armour – vambrace and breastplate, and sword trailing to the ground.

Yet these two can rightly be called the grandparents of the port of Falmouth. With their ten children, they produced a dynasty that spread far beyond Cornwall, a line of mariners and politicians, pirates and felons, diplomats and courtiers who played a part in succesive royal courts, while here in their patch of shoreside territory, they carved a fief from open fields and cliffs, and from a minor estate a port connected to the furthest points of the known world.

John and Elizabeth Killigrew.

The family was not originally from the coast. The small farm of Killigrew – meaning ‘nut-grove’ (not ‘grove of eagles’ as is often supposed) – was located to the north of Truro, half a day’s ride from the open sea. (Long after the Killigrews had gone from the town at Falmouth, the yard at Killigrew could still be seen. Not until the late 1990s was it finally destroyed, when teams of yellow earth-movers and diggers parked in it while they reshaped the land for the Trispen bypass.) It was through marriage, at about the turn of the fourteenth century, that the Killigrews became associated with the manor of Arwenack. From then on their name crops up in the records of Glasney College – as does that of John’s wife, Trewinnard. But while Penryn and Glasney prospered, safe behind their chain-barrage, Arwenack remained of little importance.

For years, the Killigrews lived the provincial life of Cornwall’s gentry, those families who owned land around the county, who married each other and visited each other in an atmosphere of leisure and conviviality. ‘A gentlemen and his wife,’ wrote Richard Carew, ‘will ride to make merry with his next neighbour, and after a day or twain those two couples go to a third, in which progress they increase like snowballs.’

With the breaking-up of the church estates and the building of the two castles at St Mawes and Pendennis, power shifted on the shores of the Fal. Like a crab with a new shell, John Killigrew crept out from under his rock and snapped up much of Glasney’s land. Soon he controlled the tithes of sixteen parishes. By buying up the south bank of the Helford, he controlled most of that river too. The land for Pendennis Castle was leased from him. Two of his sons received lucrative commissions for overseeing its building. When the castle was complete, John became its first captain and remained so for the rest of his life.

Pendennis Castle made a little king of John Killigrew, protecting Arwenack from marauding ships and fortifying his status with Crown bombards and perriers, pyramids of stone shot and keep-walls 11 feet thick. He joined that class of Tudor men who grew suddenly wealthy from the easy pickings of church land. Killigrew was particularly fortunate: not only did he have an enlarged estate and a brand-new castle, he also had the sea. The combination gave him control of one of the best anchorages in the land, and a power that was constrained by little more than the laws of wind and tide.

When Queen Mary came to the throne in 1554, and began to reverse the heretical advances of the Protestants, John Killigrew at once involved himself in the insurrection against her. Having no real authority as far west as the Fal, the new queen was forced to try to win him over. She reappointed him to his post at Pendennis. Her Privy Council confirmed his command of the castle, which he must ‘diligently, faithfullie and truly kepe, save and defende with all his power, connyng and industrie’. He and his sons did nothing diligently, faithfully or truly. They continued to plot against the Queen. Two were implicated with Sir Peter Carew in Wyatt’s rebellion. They fled to France where Henry II was happy to provide them with ships to attack the Spanish vessels of Mary’s husband, Philip II. Along with a number of other families from the Cornish and Devon coasts, the Killigrews conducted an ongoing campaign against Philip’s shipping in the Channel. Their small-time piracy, the habit of centuries among seafarers of Channel shores, became more political. The maritime historian Kenneth Andrews identifies a shift in motive at about this time: ‘the gentry took the lead, especially the west country families connected with the sea, for whom Protestantism, patriotism and plunder became virtually synonymous … the Cornish Tremaynes and Killigrews embarked on an unofficial war with Spain.’

Back and forth across the Channel the Killigrews sailed – harrying the Spanish and taking Protestant rebels into exile in France. During the hot summer of 1556 – heat which drove the frail queen to her bed – Mary’s Privy Council lost patience with the pirates. At Arwenack, John Killigrew was arrested and with his heir, also John, brought up to London. The two were thrown into the Fleet Prison. At the same time, in the Queen’s name, a small squadron was sent into the Channel to round up rebel ships. The force was commanded by the veteran pirate-hunter, Sir William Tyrell.

Tyrell had immediate success. Soon, just above the low-water mark at Wapping Stairs, six pirates swung from gibbets. He went to sea again and, according to the Acts of the Privy Council, captured ‘ten English pirate vessels’. One of the commanders escaped to Ireland in a small boat, where he was killed by local men as he struggled ashore. Another – who had escaped Tyrell for years – was Peter Killigrew.

Of all the five sons of Arwenack Manor, Peter was the best-known sea-rover. The Venetian ambassador in London described him as ‘an old pirate, whose name and exploits are most notorious, and he is therefore in great repute and favour with the French’. At first, Peter Killigrew escaped again, was recaptured, tried to stuff 150 crowns into the skirts ‘of his woman’ and was finally taken in chains to London. Twenty-four of the ordinary seamen were hanged at Southampton, and another seven at Wapping.

Peter was not killed at once. He and his brother were taken to the Tower where they later alleged they were tortured. From their confession comes a tale that resonates down the ages with an authenticity more convincing than the J. M. Barrie, dyed-in-the-wool brigand. Peter Killigrew was weary. He had known too many night chases, too many hostile landfalls, too many deceptions and betrayals. All he wished to do, he now explained, like any self-respecting mariner of the times, was to sail to the gold mines of Guinea and return with enough to retire on. He would then, he claimed, buy a house in Italy and never again put to sea.

By this time, his father had been released from the Fleet, and promised to pay compensation to anyone wronged by his miscreant sons. With their marine skills and position, the Killigrews were deemed ‘useful’. Peter Killigrew was put in charge of the Jerfalcon, part of a naval squadron active in the war against France. John and his eldest son returned to Cornwall. Within a year Elizabeth was queen and John Killigrew’s Protestant fiefdom, centred on Arwenack and Pendennis Castle, was once more in sympathy with the Crown. Pugnacious seamen like the Killigrews were no longer outlaws but set to become the very drivers of the new regime.

During the later years of his life, John Killigrew amassed a sizeable fortune. As governor of Pendennis, he continued to use the waters of the lower Fal to his advantage, in line with many of Elizabethan England’s most colourful ventures, seizing chances as they came, exploiting the legal ambiguity and anonymity of the sea. Even so, his maverick methods infuriated the state. Throughout the mid-1560s they received reports of his piracy and ‘evill usage in keeping of a castell’.

John’s son Peter may genuinely have intended to retire, to reach Guinea, and buy a house in Italy. But it was easier to carry on doing what he did best, using the Killigrew lands on the Helford river as a base for his dubious trading. Helford – nicknamed Stealford – became known as a safe haven for pirates, a place to offload and distribute plunder without risk. The Killigrews operated their own mini-state around Falmouth. When an envoy of the Privy Council was sent to Arwenack to claim 184 rubies stolen by Peter, John Killigrew – then in his seventies – reached for his sword and threatened to stick him.

With sea-gained bounty, the elderly John Killigrew set about rebuilding Arwenack Manor. Carts brought granite from Mabe quarry and, for ornament, barges of free stone from along the coast at Pentewan. Gables and high chimneys multiplied out from a three-storey central tower. A line of battlements ran along the top of the banqueting hall. A courtyard was enclosed on three sides, while on the fourth it opened onto a water-gate with a short canal dug out from the marshy ground of Bar Pool. John Killigrew’s expansion of Arwenack, according to the family’s chronicler, made it ‘the finest and most costly house in Cornwall’. The bill rose towards £6,000. But just as the last fittings were put in place, in November 1567, John Killigrew died.

The sun flashes again on his brass likeness. Half-armoured, he looks every inch the late-Tudor strongman, his stance and expression set hard against the centuries between us. Opportunistic, fiercely Protestant, equating any sense of authority with the priestly rule of the past, he found in the sea an arena in which to exercise his will with impunity, a new breed of man, a semi-licensed rogue as yet untamed, clanking out of the Middle Ages to help lay the foundations of modern Britain.

CHAPTER 4

From the decades following John Killigrew’s death comes one of the earliest and most striking images of Falmouth. Buried deep in the British Library, under ‘highly restricted’ access, the picture is bound into a volume of Christopher Saxton’s maps of England’s counties – known as the first English atlas. The volume was collated by Queen Elizabeth’s secretary of state Lord Burghley during the 1570s – a period which happened also to see the most explosive progress in the history of English seafaring.