The Levelling Sea: The Story of a Cornish Haven in the Age of Sail

In the hush of the Manuscripts Room, I rest Burghley’s volume on a foam cradle. I raise its pasteboard cover. The pages turn with a stiff and biblical crinkling. Saxton’s Atlas reveals an England of crimson villages, rivers of heavenly blue, well-spaced market towns, lime-coloured hills and a jagged coastline back-shaded with gold. Its pretty pages, each showing its bordered shire, speak of the merits of regional order, and echo Burghley’s own tireless efforts to achieve it.

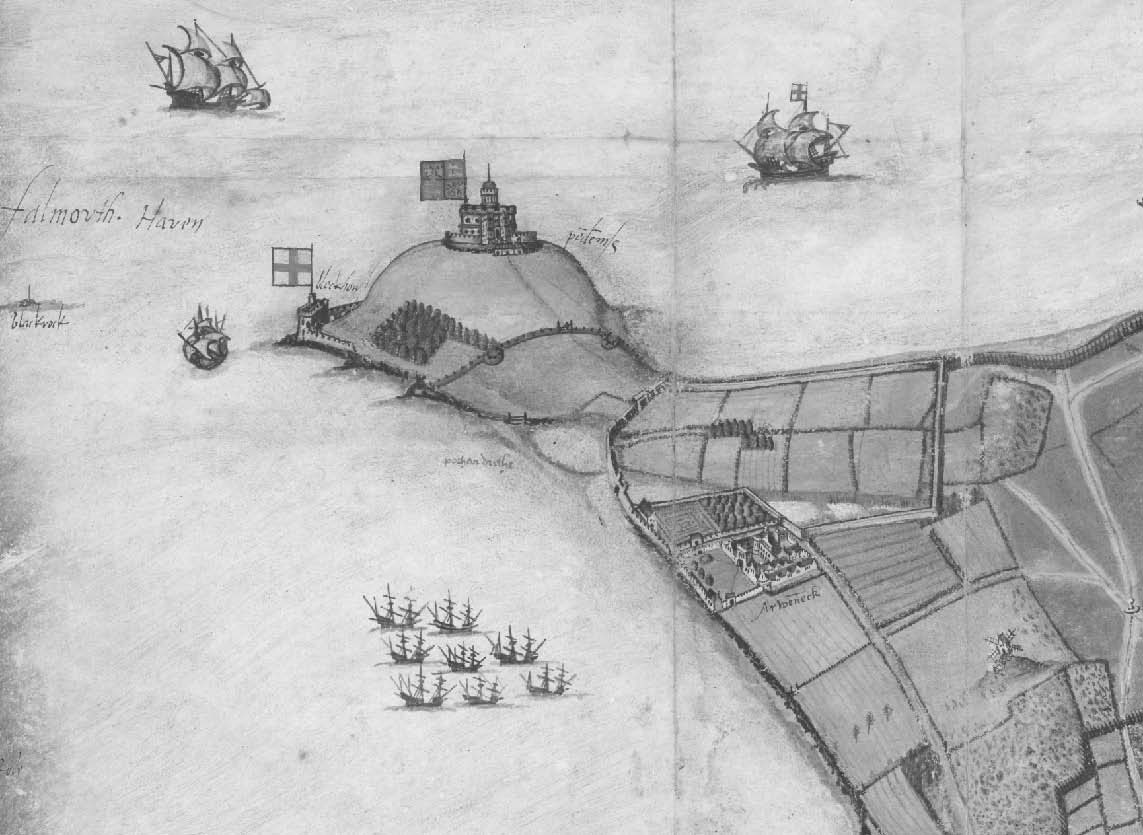

Gathered in among them, Folio 9 is of a wholly different character, less stylised and much more exuberant. An inlay of vellum in a paper frame, the folio has on its reverse the title ‘Map of Falmouth Haven’. The words are written in a curator’s pencil, lightly marking the paper, like a whisper.

I turn the page and stand back. ‘Map’ is not right. Folio 9 is a painting, a wonderful vista of greens and yellows and browns, without symbol or key, without abstraction, with none of the functionality of Saxton’s counties. A half-inch rim of black ink runs around the map’s edge, sharpening its earthy tones. The image itself is a bird’s-eye view of the familiar shoreline of the lower Fal – the view of a lark somewhere high above Feock. It is early summer. The hedges are full. Woods and copses are thick with new growth, mounds of fresh-cut hay dry in the fields. You can sense the air’s fly-buzz and gorse-scent, follow the winding lanes, and feel beneath your feet the soft-grass ridge between the cart-furrows. But the image is really about the water: from almost every slope stretch the tidal tributaries and the pale-blue estuary of the Carrick Roads.

One of the first things you notice about the Burghley Map of Falmouth Haven is that it is upside down. The traditional south–north orientation is reversed. It does not, as you expect, start out at sea and guide you up from the Lizard towards the sheltering channel of the Fal. Folio 9 brings you in from the north, from the land, leads the gaze up and outwards into open space. Falmouth is no longer merely a bolt-hole for ships, or a handy aperture for the kingdom’s enemies. It is here presented as a conduit to the empty horizon. The overall effect is an urging, a siren cry: leave behind the old terrestrial certainties! Join in the great sea-based bonanza!

Detail from the Burghley Map of Falmouth Haven.

A glow of patriotism radiates from the manuscript. The castles appear jaunty and solid. Over the lower blockhouse of Pendennis rises a St George flag so large that it looks set to topple the little tower. From the castle itself flutters a Royal Standard of impossible size – peer closely and you can see the gilded symbols flashing like tiny jewels: six rampant passant lions, one rampant, and the curves of the Irish harp.

By contrast, the ancient town of Penryn, with its outdated, pre-Reformation dominance, is shunted to the bottom of the map. The cross-river chain is shown, and below it the remains of Glasney College. Years earlier, before the Norman Conquest, Penryn had been one of Cornwall’s largest population centres, second only to the county town, Launceston. Here it is almost ignored, pressed to the margins, where four centuries of thumb-grasps and page-turnings have flaked the paint so that the town now looks to be in the midst of a snowstorm.

Where Falmouth will emerge during the coming century there is just shale and shingle in the very slight recess of Smithwick Creek, and on the cliff above, open ground. Only one building is drawn, a low shed marked lym-kiln. The great port has its lowly origins here: on an empty beach, in the swampy ground above, and in the cob-walls of a small lime-kiln.

Dominating the picture, dwarfing the ancient town of Penryn, is Arwenack Manor, the most opulent and expensive house in Cornwall. Placed between Pendennis Castle above and Penryn below, the house appears in style to be the child of both. With its battlements and towers, it has taken on the martial character of Pendennis. But in the courtyards, the mullioned windows and the long facade, the vast manor carries an ironic resemblance to Glasney College whose destruction allowed the Killigrews to create it. Aglow with Protestant triumphalism, surrounded by its neatly fenced demesne land, it fills the map with its worldly fortitude.

Such is the precedence given to Arwenack that the whole image suggests a piece of propaganda for the Killigrew family. It is usually assumed that Burghley himself commissioned the map, yet although he bound other manuscript maps into Saxton’s Atlas, Falmouth is the only large-scale depiction of a harbour. Whether he asked for it or whether it was presented to him unsolicited is not clear.

The Killigrew family and Lord Burghley were certainly known to each other. Burghley would have been aware of old John, Pendennis’s first governor, his sudden rise, his imprisonment, his pirate son Peter and all the nefarious sea-tales of the family. But he also knew more directly, from court, two of the sons who were rather better behaved. William Killigrew was an MP, who in his career represented Cornish constituencies in a total of seven Parliaments (no Cornish family of the time provided more MPs than the Killigrews). William was also Groom to Elizabeth I’s Bed Chamber. His brother Henry Killigrew was even closer to the Queen’s inner circle, by turns Teller of the Exchequer and Surveyor of the Armoury, and her chosen envoy on a number of vital missions to Scotland, France and the Netherlands. But the closest link was that Henry Killigrew and Lord Burghley were married to sisters, the famous daughters of Sir Anthony Cooke (a third was married to Sir Nicholas Bacon).

An upbringing in the rowdy atmosphere of Arwenack, with its visiting ships, its Huguenot rovers and Dutch sea-beggars, had prepared Henry Killigrew for an adventurous political career. He spent Mary’s reign in exile and perfected his French and Italian. He was not a tall man and acquired a permanent limp from a wound picked up in the siege of Rouen in 1562. When he was released, and Rouen relieved, it seemed Elizabeth and England were in the ascendant. Henry Killigrew wrote to his wife’s brother-in-law, Lord Burghley (then William Cecil): ‘God prosper you as He has begun, and inspire her Majesty to build up the temple of Jerusalem.’

Burghley has annotated each of his county maps with a list of its ‘justices’. There is a sense of him trying to order the kingdom, to catalogue it for better governance – or any governance. In Mortlake, the mystic John Dee was building a mythical Jerusalem for his queen, while Burghley, the great administrator, was assembling the more solid building-blocks for a civil state.

But Lord Burghley and the Killigrews of Arwenack were also at odds. In their respective attitudes to the sea, each represents a distinct thread of English interests which, when wound together, stretched taut through the coming centuries. One was legitimate, using the sea for the collective good; the other was illegal, exploiting it for private gain. One produced the Royal Navy, the other spun off into piracy. Each developed seamanship and a certain arrogance at sea, contributing in its own way to the victories of Drake, Cochrane and Nelson.

Burghley was among those who understood that the country’s future – indeed its survival – lay in naval strength. He took personal control of the political aspects of the Royal Navy, and spent the 1560s and 1570s building up capacity, commissioning surveys of shipping and mobilising. He had a great love of geography and his copy of Saxton’s Atlas also includes a map of the coast of Norway, Sweden and northern Russia. He was famous for his meticulous knowledge of the places of Europe. Yet he himself left British shores only once in his life, for a brief visit to the Low Countries.

The rise in piracy, represented by the Cornish Killigews, angered him; fish were the rightful yield of the seas, not plunder. Those who lived by the coast should spread nets to feed the people, not sail off on prize-grabbing adventures. But since the Reformation, and the relaxation of fast days, demand for fish had shrunk: to eat meat on a Friday, to roll your jaws over bloody slabs of beef, became an affirmation of Protestant faith, and it left fishermen with a shrinking market. They stowed their nets and joined privateers. To try to induce them back, Burghley – still William Cecil at the time – introduced a government bill to make twice-weekly fish-eating compulsory. His measure was jeered in the House for its Popish implications, and dubbed ‘Cecil’s Fast’.

The Killigrews on the other hand saw the sea as a source of personal gain. Arwenack became a hub for the illicit side of seaborne enterprise, for privateering, a practice which took off during the last decades of Tudor rule. Elizabethan ‘privateering’ was, strictly, distinct from the seventeenth-and eighteenth-century practice which spawned the term, but it offered the same dubious licence to attack foreign ships as redress for lost cargoes. In the sixteenth century, this licence was provided through a ‘letter of marque’. If a merchant or captain was robbed of his goods by a foreign power, he was given a chit which allowed him to snatch compensation in kind from any ships of that power. Often the letters themselves were exchanged for money, and often not held at all. In practice, privateering was little more than semi-sanctioned piracy.

To Burghley, it made a mockery of the rule of law, and jeopardised relations with other nations, particularly Spain. But with hindsight, the spirit of privateering characterises the Elizabethan age – the ship as the vessel of the wildest hopes, the heady myth-making, the heroic sea voyages, the failure of the Spanish Armadas. Privateering also had one great practical benefit: it proved the nation’s greatest school for maritime skills.

The countless and nameless figures who manned the privateers learned the advantages of the modern rig with its auxiliary sails. They learned to use the mesh of halyards and lifts and sheets. They learned how to charge the guns with volatile serpentine powder, and how to damp the recoil. And they learned something far more important, that despite the risks and discomforts, a successful foray into the Channel, or the taking of a Spanish prize, could bring greater reward than a lifetime of toil. The sea and quick wealth become part of a powerful association for coastal communities, brought together in the arts of seamanship.

Life on board a privateer was brutal and anarchic, lacking either the hierarchical order of Spanish ships or the fierce discipline of the later Royal Navy. Privateers were mutual enterprises, operated on the same basis as fishing boats, with the crew receiving no wages but reaping a third of the takings. They would coerce the captain if they disagreed with him – ‘shite on thy commissions!’ – or simply mutiny. There were open fights. The ships were often shockingly overmanned and under-victualled. Scurvy and the flux laid whole companies low; there were instances of starvation. But when a prize was sighted, all disputes were forgotten. The men took to their stations, gaining the weather-gage, firing on the prize not to sink it but to disable it. With small arms – fowlers and murderers, muskets and calivers – the ship was boarded. If booty was not revealed by searching, it was discovered by persuasion – wrapping ropes around the head, or bowstrings around the genitals.

As well as rewarding those with sea-skills, such enterprise encouraged private investment in ships. By the end of the century, the English merchant fleet outnumbered the Queen’s own by twenty to one. The ships landed up to £200,000 a year in illicit prize money, establishing new fortunes, no longer tied up in land, as liquid as the sea that yielded them, a fund of robber capital that grew and grew, doubling by the decade, funding more ships and more ventures, and swelling through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries into the prosperity on which Britain’s global power was based.

On the Burghley Map, ships fill the blank sea-spaces with gleeful profusion. To the west of Pendennis an English three-master fires, rather gratuitously, on a caravel (its southern shape suggesting devious papist intentions). Another three-master waits to the south of Pendennis. In the Carrick Roads, marked by a couple of paddock-size St George’s ensigns, a powerful squadron lies at anchor. But there are other ships, too, which fly no official flags. Mylor has a couple, St Mawes a couple more (Penryn has none); three more lie off St Methick’s Point. But the greatest number, arranged in neat formation, lie off Killigrew land, a cluster of eight off Arwenack Manor.

Burghley’s own handwriting has been identified on his map of Falmouth Haven and it is easy to imagine him during the dangerous years of the late sixteenth century, surveying his atlas and pausing to scrutinise Folio 9. He would have ignored the Killigrews’ display of standard-waving from Pendennis Castle, seeing it for the sham it was, likewise the bellicose men-of-war. But he would have noticed, too, that anonymous group off Arwenack, their pack-like poise and confidence, and been reminded of the renegade threat of privateering.

Their rig is identical. Three masts, two bare yards on the fore and main, and a spar aft on the mizzen. A bumpkin juts from a high transom stern. The images are too small to see what guns they carry – typically a clutch of sakers, minions and falconets. They are not big, perhaps fifty or sixty tons burden, easily affordable for a private syndicate – but in the history of ship design they represented the most efficient vessels that had ever sailed.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, sailing ships had evolved more quickly than in the previous 5,000 years. Such was their success that they remained essentially unchanged for the next 200 or 300 years, until the coming of steam and ironclads began to make them obsolete. With only a little hyperbole, the maritime historian Alan McGowan equates the development of this type of rig with the discovery of fire and the invention of the wheel.

The standard sailing ship in most of Europe had, until well into the Middle Ages, tended to use a large, single sail, a very powerful driving force if the wind was steady, and moderate, and blowing from behind, or at least aft of the beam. Such a rig was pretty useless to windward and gave little scope for varying sail area in light airs or as the breeze freshened. So auxiliary sails were added – a maintop above the maincourse and ahead of them a foretop and forecourse. In time a spritsail appeared in the bows and lateen sails were set aft – which enabled the ship to manoeuvre through the wind with an ease never known before. A fourth mast and bonnets were sometimes added. Over time, sails grew upwards – top-gallants, royals and skysails – while the headsails pushed forward, out along the bowsprit. Staysails filled the gaps ahead of and between the masts while, eventually, studding-sails stretched far out over the sides.

From the Bayeux Tapestry.

As to the hulls of northern European ships, they had tended to be clinker-built. The strength lay in the overlapping boards; an inner frame was added later, towards launching. When demands on ships grew, and voyages became longer and the risks from hostile ships increased (or rather, in the case of English privateers, the rewards from being hostile oneself), an alternative construction became popular, spreading from Spain and Portugal. Carvel building placed the boards of the hull flush against one another and relied for firmness and shape on an inner frame of ribs and crosspieces. (It is possible that, in Cornwall and Brittany, carvel construction had always been practised; the Veneti were reported to have used such ships against the Romans.)

Carvel building also helped solve one of the greatest problems of sixteenth-century fighting ships: how to mount heavy guns on board in a way that would be efficient in battle and not compromise seaworthiness. Having one large gun to fire from the bows suited the Venetians with their great galleys but in the waters of northern Europe, despite many attempts, galleys never really worked. Although bow-mounted guns and stern-chasers were fixed well into the seventeenth century, it was the broadside arrangement that decided the outcome of countless battles. The carvel structure allowed ports to be cut in the ship’s sides without undermining their strength; in England, developments in iron-founding swept aside the constraints of expensive bronze barrels. Arming a ship, to the alarm of men like Burghley, became possible not only for the Crown but for privateers such as those of the Killigrews.

For want of a better model, early tactics at sea had followed the orthodoxies of land battle. The Spanish in particular took on board a military mentality based on strict rank, fortresses and close combat. They built ships with ever more elaborate upperworks. Soldiers would assemble for attack high in the floating arcades while sailors, with the status of water-carriers, performed their strange business with canvas and cordage. European kings were slow to see the strategic value of smaller, free-ranging fleets, preferring the ships they built to reflect their own magnificence. The Swedish king built the 230-foot Elefant. James IV of Scotland went one foot bigger with the Great Michael, which encouraged Henry VIII to join in and build the Henry Grace à Dieu. When he sailed to meet Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, the gilded sails glowed like the morning sky. Francis I himself took royal hubris further with the Grand François: a crew of 2,000, an onboard windmill, tennis court and chapel. Before even reaching the open sea, the Grand François was wrecked.

The success of English ships from the 1570s onwards stemmed in large part from leaving behind land-based hierarchies and abiding by the laws of the sea. Ventures were plotted in small harbours, in shoreside manors like Arwenack, not in court. Ships were self-contained, small-scale units of enterprise and power, and in Elizabethan England their design developed accordingly, producing compact and agile craft. Far from shore, and in the capricious hands of wind and waves, the spirit on board was more egalitarian than anywhere on land. ‘I must have the gentleman to haul and draw with the mariner,’ declared Drake on his circumnavigation, having just executed the troublesome courtier Doughty.

Even now, though, it is hard to glean very much about sixteenth-century ship design. The preserved boards of the Mary Rose are among the few actual relics. Otherwise there are only chance images – tapestries in Portugal, paintings in the Alhambra, the seal of Louis de Bourbon, Henry VI’s psalter, chest designs, or manuscripts like that of Anthony Anthony or Burghley’s folio of Falmouth Haven. From these sources, a vague outline of development can be traced. Masts grow in number along the deck, yards sprout from them. A bow-rigged flagstaff in one period has mutated into a spritsail in the next. Sometimes a ship will be shown with an experimental spar, which then disappears like some redundant limb. Rarely has the growth of a technology so closely mirrored biological evolution.

The vessels themselves have long since vanished, wrecked or destroyed by fire, or after countless gravings and rebuildings and re-riggings, the cutting down of decks, stripped of all blocks and fittings, then taken up some muddy creek to settle slowly back to nature, their timbers broken down by the drilling shell of shipworms. Like some race of aquatic dinosaurs, Tudor ships have been reassembled from the faintest of traces. But in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge is a set of papers that gives the only detailed glimpse of the process and thinking behind their construction, and of this decisive moment in man’s relationship with the sea.

CHAPTER 5

Storm-clouds press down dark and close above the Fens. I scuttle across Magdalene’s quads just as the first patter of rain rises to a crescendo. It is the day after seeing the Burghley Map, and now in the upper room of the Pepys Library, with the same thrill of expectation, and to the sound of approaching thunder, I lay out another ancient volume, between another pair of pasteboard covers.

When he died, Samuel Pepys left a collection of some 3,000 books. Among the large number concerning maritime history was a series of loose folios which he had bound into a volume, naming it Fragments of Ancient English Shipwrightry. They include the country’s earliest record of paper plans for building ships. Looking at them, you can sense the process of experimentation, with the dividers’ prick-marks still visible, and the arcane grids of hull curves framed with marginal calculations. Other folios place the art of shipbuilding in a much wider context. Included by Pepys is a painted image of Noah’s Ark – ‘Noah did according unto all that God commanded him even so did he make thee an arke of pine trees …’ Another page has jottings about Jason’s voyage to Colchis, and the invention of ships in the Hellespont. The overall impression is less of an inquiry into a practical problem than a quest to rediscover some lost secret – closer to the spirit of the Renaissance than the Enlightenment.

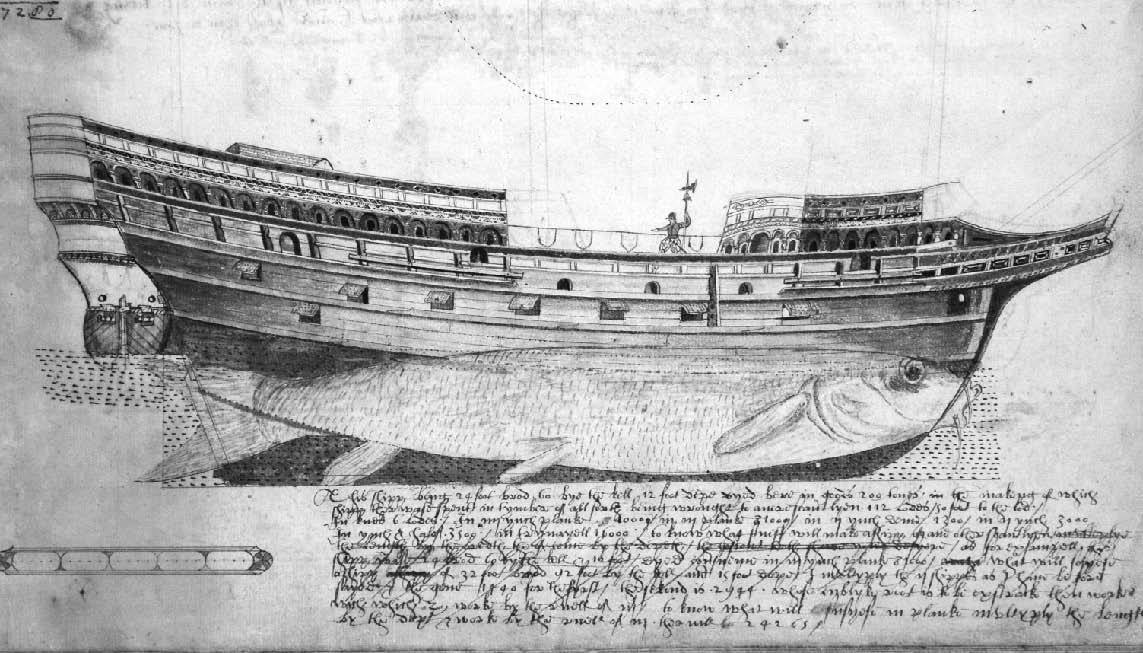

The papers are attributed to Matthew Baker, greatest of Elizabethan shipwrights. Baker was the first to leave a record of the abstraction of hull design into numerical proportions, the first to have a ship built from his blueprints (the private warship Galleon). It was he who built the Revenge, Drake’s flagship in 1588, from whose decks Grenville later fought the most famous rearguard action in English history. Martin Frobisher’s three Baffin Island expeditions used Baker’s ships. In his Seaman’s Secrets John Davis said that as a shipwright Baker ‘hath not in any nation his equall’. To many of his contemporaries, Baker’s craft put him on a par with Vitruvius and Dürer.

Among his bound papers in the Pepys Library is what is believed to be a self-portrait. Baker is shown standing at his plan table which is spread with instruments of drawing and mensuration. He holds a pair of dividers and is marching them over the drawing of a hull. The dividers are exaggerated, some three feet high, and there is something faintly comic about the image. Though Baker’s head is bent in earnest concentration, his left leg is kicked up behind him, giving the impression that he is skipping as he works.

It is Baker who is credited with the design that revolutionised English shipping. Rejecting the cumbersome, castellated upperworks that compromised ships’ seaworthiness, he helped develop a much lower, sleeker form, recognisable in the shapes of those on the Burghley Map lying off Arwenack Manor. Initial resistance to the new hull shape came, it seems, from Queen Elizabeth and Lord Burghley (as well as possibly from John Hawkins, the Navy’s treasurer to whom, paradoxically, Baker’s innovation is often attributed). Baker had a battle to fight in gaining approval for his revolutionary design, a battle that produced the most unusual image in his collection.

Baker has used a fish. He has transposed the profile of an Atlantic cod below the waterline of his ship. The curve of the fish’s belly gives the distinctive ‘crescent’ shape to the keel. The long upward slope towards the tail represents the pinching of the floor that produces the sharp and narrow after-keel section. (The convention of good ship design was long framed in the expression ‘cod’s head and mackerel tail’, which persisted for yachts right up to the 1960s, when the convention was suddenly reversed, the sleek tail in the bows, and the bulk of the beam aft.)

Baker’s cod is not an exact fit, the cod’s distinctive fat lips stick through the stem while the flukes of the tail do not correspond to very much. But that makes its use more interesting. Clearly, the cod was persuasive.

From Fragments of Ancient English Shipwrightry.