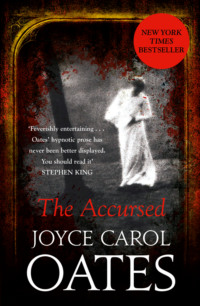

The Accursed

“These are terrible events, Yaeger, but—why are you telling me about them, at such a time? I am upset too, of course—as a Christian, I cannot countenance murder—or any sort of mob violence—we must have a ‘rule of law’—not passion—but—if law enforcement officers refuse to arrest the guilty, and local sentiment makes a criminal indictment and a trial unlikely—what are we, here in Princeton, to do? There are barbarous places in this country, as in the world—at times, a spirit of infamy—evil . . .”

Woodrow was speaking rapidly. By now he was on his feet, agitated. It was not good for him, his physician had warned him, to become excited, upset, or even emotional—since childhood, Woodrow had been an over-sensitive child, and had suffered ill health well into his teens; he could not bear it, if anyone spoke loudly or emotionally in his presence, his heart beat rapidly and erratically bearing an insufficient amount of blood to his brain, that began to “faint”—and so now Woodrow found himself leaning forward, resting the palms of his hands on his desk blotter, his eyesight blotched and a ringing in his ears; his physician had warned him, too, of high blood pressure, which was shared by many in his father’s family, that might lead to a stroke; even as his inconsiderate young kinsman dared to interrupt him with more of the lurid story, more ugly and unfairly accusatory words—“You, Woodrow, with the authority of your office, can speak out against these atrocities. You might join with other Princeton leaders—Winslow Slade, for instance—you are a good friend of Reverend Slade’s, he would listen to you—and others in Princeton, among your influential friends. The horror of lynching is that no one stops it; among influential Christians like yourself, no one speaks against it.”

Woodrow objected, this was not true: “Many have spoken against—that terrible mob violence—‘lynchings.’ I have spoken against—‘l-lynchings.’ I hope that my example as a Christian has been—is—a model of—Christian belief—‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’—it is the lynchpin of our religion . . .” (Damn!—he had not meant to say lynchpin: a kind of demon had tripped his tongue, as Yaeger stared at him blankly. ) “You should know, Yaeger—of course you know—it has been my effort here, at Princeton, to reform the university—to transform the undergraduate curriculum, for instance—and to instill more democracy wherever I can. The eating clubs, the entrenched ‘aristocracy’—I have been battling them, you must know, since I took office. And this enemy of mine—Dean West! He is a nemesis I must defeat, or render less powerful—before I can take on the responsibility of—of—” Woodrow stammered, not knowing what he meant to say. It was often that his thoughts flew ahead of his words, when he was in an emotional mood; which was why, as he’d been warned, and had warned himself, he must not be carried away by any rush of emotion. “—of confronting the Klan, and their myriad supporters in the state, who are not so many as in the South and yet—and yet—they are many . . .”

“ ‘Supporters’ in the state? Do you mean, ‘law-abiding Christian hypocrites’? The hell with them! You must speak out.”

“I—I must—‘speak’—? But—the issue is not so—simple . . .”

It had been a shock to Woodrow, though not exactly a surprise, that, of the twenty-five trustees of Princeton University, who had hired him out of the ranks of the faculty, and whose bidding he was expected to exercise, to a degree, were not, on the whole, as one soon gathered, unsympathetic to the white supremacist doctrine, though surely appalled, as any civilized person would be, by the Klan’s strategies of terror. Keeping the Negroes in their place was the purpose of the Klan’s vigilante activities, and not violence for its own sake—as the Klan’s supporters argued.

Keeping the purity of the white race from mongrelization—this was a yet more basic tenet, with which very few Caucasians were likely to disagree.

But Woodrow could not hope to reason with Yaeger Ruggles, in the seminarian’s excitable mood.

Nor could Woodrow pursue this conversation at the present time, for he had a pressing appointment within a few minutes, with one of his (sadly few) confidants among the Princeton faculty; more urgently, he was feeling unmistakably nauseated, a warning signal of more extreme nausea to come if he didn’t soon take a teaspoonful of the “calming” medicine prescribed to him by Dr. Hatch, kept in a drawer in the president’s desk.

“Well, Yaeger. It is a terrible, terrible thing—as you have reported to me—a ‘lynching’—alleged . . . We may expect this in south Jersey but not in Camden, so near Philadelphia! But I’m afraid I can’t speak with you much longer, as I have an appointment at . . . Yaeger, what on earth is wrong?”

Woodrow was shocked to see that his young kinsman, who had always regarded Woodrow Wilson with the utmost respect and admiration, was now glaring at him, as a sulky and self-righteous adolescent might glare at a parent.

The carelessly shaven jaws were trembling with disdain, or frank dislike. The nostrils were widened, very dark. And the eyes were not so attractive now but somewhat protuberant, like the eyes of a wild beast about to leap.

Yaeger’s voice was not so gently modulated now but frankly insolent: “What is wrong with—who, Woodrow? Me? Or you?”

Woodrow protested angrily, “Yaeger, that’s enough. You may be a distant relation of mine, through my father’s family, but that—that does not—give you the right to be disrespectful to me, and to speak in a loud voice to upset my staff. This ‘ugly episode’—as you have reported it to me—is a good example of why we must not allow our emotions to govern us. We must have a—a civilization of law—and not—not—anarchy.”

Stubbornly Yaeger persisted: “Will you talk to Winslow Slade, at least? If he could preach from his pulpit, this Sunday—that would be a good, brave thing for Princeton; and maybe it would get into the newspapers. And if the president of Princeton, Woodrow Wilson, could give a public comment also—”

“Yaeger, I’ve told you! I can’t discuss this now. I have an appointment at three-fifteen, and I—I am not feeling altogether well, as a consequence of our exchange.”

“Well, I’m sorry for that. Very sorry to hear that.”

(Was Yaeger speaking sarcastically? Woodrow could not bring himself to believe so.)

Woodrow wanted to protest: he was a friend to the Negro race, surely!

He was a Democrat. In every public utterance, he spoke of equality.

Though he did not believe in women’s suffrage—certainly. Very few persons of his close acquaintance, including his dear wife, Ellen, believed in so radical and unnatural a notion.

Woodrow would have liked to explain to Yaeger how systematically and explicitly he was fair-minded toward Negroes. Over the protests of certain of the trustees and faculty, he saw to it that Booker T. Washington was not only invited to his Princeton inauguration, as a sensible, educated Negro promoting a “gradualism” of racial reform, unlike the radical

W. E. B. DuBois, but that the Negro educator was asked to give one of the speeches at the ceremony, alongside several of the most distinguished white persons of the day.

Also, Booker T. Washington had been made welcome at a commencement luncheon at Prospect, where he’d been seated among the other guests in a most relaxed manner; though an invitation to a lavish dinner at the Nassau Club, given the night before, had not been extended to him, since the Nassau Club did not admit Negroes onto its premises (except as servants). That, President Wilson had been powerless to modify, since the Nassau Club was a private club.

In addition, Professor van Dyck of the Philosophy Department often told the tale of how one Reverend Robeson, of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church, had aspired to a meeting with the president of Princeton University, to suggest that his son Paul, allegedly an “outstanding” student and athlete, be admitted to the university; scarcely knowing, from the courtesy with which Woodrow Wilson greeted this remarkable request, how audacious it was; and how gentlemanly Wilson’s reply—“Reverend, I am sure that your son is indeed ‘outstanding.’ But it is not quite the right time in history for a Negro lad to enroll at Princeton—that time, I am afraid, will not be for a while.” So long as Negroes—darkies, as they were more fondly called, in Woodrow’s childhood—knew their place, and were not derelict as servants and workers, Dr. Wilson had very little prejudice against them, in most respects.

“Yes,” Yaeger said, with a turn of the knife-blade, not unlike the cruelty of an adolescent boy with regard to his father, “it would be tragic if you were not feeling ‘altogether well’—as a consequence of my unwelcome appeal.”

In a part of Woodrow’s mind, or of his heart, which was hardly so calloused as Yaeger Ruggles seemed to be implying, Woodrow was deeply wounded, that the young man he so cared for seemed now scarcely to care for him. Stiffly he said:

“There is some mystery here, Yaeger, I think—as to why you are so very—so very concerned . . .”

“ ‘Mystery’? D’you think so, Woodrow?” Yaeger spoke with an insolent smile; all this while he had been smiling at his elder kinsman, a mirthless grin, like the grimace of a gargoyle. He too was agitated, and even trembling, but he could not resist a parting riposte as he prepared to leave the president’s office, “You have never looked at me closely enough, ‘Cousin Woodrow.’ If you had, or if you were capable of such insight, you would know exactly why I, and others like me in this accursed United States of America, are so very concerned.”

As Yaeger turned away contemptuously yet Woodrow saw, suddenly—saw the young man’s facial features, his lips, nose, the texture and tone of his skin, even the just-perceptible “kinkiness” of his hair—saw, and, in a rush of sickening horror, understood.

PRESIDENT WILSON! OH—President Wilson!

Are you all right? Did you injure yourself? Let us help you to your feet—back to your desk . . .

Shall we summon Dr. Hatch? Shall we summon—Mrs. Wilson?

NEITHER DR. HATCH nor Mrs. Wilson was summoned. For Woodrow was quite recovered, within minutes.

Yet, he had had enough of Nassau Hall, for the day.

Though unsteady on his feet, and ashen-faced, yet President Wilson insisted upon walking unassisted to the president’s mansion, Prospect, located at the heart of the university campus: an austere example of Italianate architecture built by the architect John Notman, that was the president’s home.

Something of a fishbowl, Woodrow thought the house. And Ellen and their daughters were made to feel self-conscious there—for prankish undergraduates could circle the house at will, in the dark, peeking into windows beneath blinds.

Still, Prospect was a very attractive and imposing residence. And Woodrow was unfailingly grateful that he lived in it; and not, as fate might have devised, another man.

Fortunately, Ellen was out. The girls were still at school. Clytie and Lucinda were in the cellar doing laundry—the smells of wet things, a deeper and harsher smell as of detergent and even lye soap provoked in Woodrow one of his memory pangs of childhood, that increased his sense of excited unease and dread.

It was a household of females. So often, he could not breathe.

Yet this afternoon he was allowed unimpeded to ascend to the dim-lit atmosphere of the master bedroom where, in the privacy of his step-in closet, he was free to select a pill, a second pill, and a third pill from his armamentarium of pills, medicines, and “tonics”—that rivaled his mother’s armamentarium of old.

Woodrow’s dear mother! How he missed her, in his weak moods especially.

She could guide him. She could instruct him in what course to take, in this matter of his nemesis Dean West.

As to the matter of the ugly Klan lynching—Mrs. Wilson would not have spoken of so obscene an event, if she had even heard of it.

For there are some things too ugly for women to know of. Genteel Christian women, at least.

A man’s responsibility is to shield them. No good can come of them knowing all that we must know.

Woodrow’s Southern relatives would have pointed out that mob violence against Negroes was a consequence of the abolition of slavery—blame, if there be blame, must be laid where it is due, with the abolitionists and war-mongers among the Republicans.

The defeat of the Confederacy was the defeat of—a way of civilization that was superior to its conqueror’s.

Hideous, what Yaeger Ruggles had revealed to him!—he who had liked the young man so much, and had, precipitously perhaps, appointed him a Latin preceptor.

That appointment, Dr. Wilson would have to rethink.

And perhaps too, he must have a private conversation with Reverend Shackleton, head of the Princeton Theological Seminary.

Unfair! And very crude! The charges Yaeger Ruggles had brought against him.

In such times of distress it was Woodrow’s usual routine to soak a compress in cold water, lie on his bed and position the compress over his aching eyes. Soon then he felt a shuddering voluptuous surrender to—he knew not what.

The Bog Kingdom. Bidding him enter! Ah, enter!

There, all wishes are fulfilled. The more forbidden, the more delicious.

He had not had the energy to undress. Only his black-polished shoes had been removed. Carefully placed side by side on the carpet.

So unmoving Woodrow was in sleep, he hardly risked rumpling his white cotton shirt, his vest and neatly pressed trousers. So still did he sleep, at such times, he did not risk sweating and dampening his clothing.

Yet, his thoughts raged like hornets.

Never can I tell Ellen. The poor woman would be distraught, appalled—the deceptive young “cousin” has come into our house, at my invitation; he has sat at my dining room table, as my guest; he has exchanged conversations with my dear daughters . . .

Now the full horror of the revelation washed over Woodrow—the danger in which he’d put, in all ignorance, his Margaret, his Jessie, and his Eleanor.

2.

It was a secret late-night meeting on the very eve of Ash Wednesday, recorded in no document except, in code, in the diary of Woodrow Wilson for March 1905.*

It was, one might say, a clandestine meeting. For so Woodrow Wilson, troubled in spirit, considered it.

I will implore him. I will humble myself, and beg for help.

I am not proud—no longer!

This meeting, more than the earlier meeting between Woodrow Wilson and his impetuous young kinsman Yaeger Ruggles, marks the first true emergence of the Curse; as an early, subtle and easily overlooked symptom marks the emergence to come of a deadly disease.

As, one might say, the early symptoms of Woodrow Wilson’s breakdown, stroke and collapse of May 1906 were prefigured here, in the events of this day, unsuspected by Woodrow Wilson, his family and his most trusted friends.

For that evening, after dinner, feeling more robust, though his brain was assailed by a thousand worries, Woodrow decided to walk a windy mile to Crosswicks Manse on Elm Road, the family estate of the Slades. It had been his request to see Reverend Winslow Slade in private, and in secrecy, at 10 p.m. precisely; Woodrow, who had a boyish predilection for such schemes, as a way of avoiding the unwanted attention of others, was to enter the dignified old stone house by a side door that led into Reverend Slade’s library, and bypass the large rooms at the front of the house. For this was not a social meeting—there was no need to involve any of the household staff or any of Dr. Slade’s family.

The last thing Woodrow Wilson wanted was to be talked-of; to be the object of speculation, crude gossip.

His dignity was such, yes and his pride: he could not bear his name, his reputation, his motives so besmirched.

For it was beginning to be generally known in Princeton, in this fourth and most tumultuous year of his presidency of the university, that Woodrow Wilson was encountering a cunning, ruthless, and unified opposition led by the politically astute Dean Andrew Fleming West, whose administrative position at the university preceded Woodrow’s inauguration as president; and who was reputed to be deeply aggrieved that the presidency, more or less promised to him by the board of trustees, had unaccountably been offered to his younger rival Woodrow Wilson, who had not the grace to decline in his favor.

All this rankled, and was making Woodrow’s life miserable; his primary organ of discomfort was his stomach, and intestines; yet nearly so vulnerable, his poor aching brain that buzzed through day and night like a hive of maddened hornets. Yet, as a responsible administrator, and an astute politician, he was able to disguise his condition much of the time, even in the very company of West, who confronted Woodrow too with mock courtesy, like an unctuous hypocrite in a Molière comedy whose glances into the audience draw an unjust sympathy, to the detriment of the idealistic hero.

Like a large ungainly burden, a steamer trunk perhaps, stuffed with unwanted and outgrown clothing, shoes and the miscellany of an utterly ordinary and unexamined life, Woodrow Wilson sought to carry the weight of such anxiety to his mentor, and unburden himself of it, at his astonished elder’s feet.

It would not be the first time that “Tommy” Wilson had come to appeal to “Win” Slade, surreptitiously; but it would be the final time.*

“Woodrow, hello! Come inside, please.”

A gust of wind, tinged with irony, accompanied Woodrow into the elder man’s library.

Reverend Slade grasped the younger man’s hand, that was rather chill, and limp; a shudder seemed to run from the one to the other, leaving the elder man slightly shaken.

“I gather that there is something troubling you, Woodrow? I hope—it isn’t—anything involving your family?”

Between the two, there had sometimes been talk, anxious on Woodrow’s side and consoling and comforting on Winslow’s, about Woodrow’s “marital relations”—(which is not to say “sexual relations”—the men would never have discussed so painfully private a matter)—and Woodrow’s disappointment at being the father of only girls.

Woodrow, breathless from the wind-buffeted walk along Elm Road, where streetlights were few, and very little starlight assisted his way, and but a gauze-masked moon, stared at his friend for a moment without comprehending his question. Family? Was Winslow Slade alluding to Woodrow’s distant “cousin”—Yaeger Washington Ruggles?

Then, Woodrow realized that of course Winslow was referring to his wife, Ellen, and their daughters. Family.

“No, Winslow. All is well there.” (Was this so? The answer came quickly, automatically; for it was so often asked.) “It’s another matter I’ve come to discuss with you. Except—I am very ashamed.”

“ ‘Ashamed’? Why?”

“But I must unburden my heart to you, Winslow. For I have no one else.”

“Please, Woodrow! Take a seat. Beside the fire, for you do look chilled. And would you like something to drink?—to warm you?”

No, no! Woodrow rarely drank.

Out of personal disdain, or, if he gave thought to it, out of revulsion for the excess of drinking he’d had occasion to observe in certain households in the South.

Woodrow shivered, sinking into a chair by the fireplace that faced his gracious host. Out of nervousness he removed his eyeglasses to polish them vigorously, a habit that annoyed others, though Winslow Slade took little notice.

“It is so peaceful here. Thank you, Dr. Slade, for taking time to speak with me!”

“Of course, Woodrow. You know that I am here, at any time, as your friend and ‘spiritual counselor’—if you wish.”

In his heightened state of nerves Woodrow glanced about the library, which was familiar to him, yet never failed to rouse him to awe. Indeed, Winslow Slade’s library was one of the marvels of the wealthy West End of Princeton, for the part-retired Presbyterian minister was the owner of a (just slightly damaged and incomplete) copy of the legendary Gutenberg Bible of 1445, which was positioned on a stand close by Winslow’s carved mahogany desk; on another pedestal was an early, 1895 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. And there were first editions of works by Goethe, Kant, Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, Schleiermacher, Ritschl, James Hutchinson Stirling and Thomas Carlyle among others. In his youth Dr. Slade had been something of a classics scholar, and so there were volumes by Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and others in Greek, as well as Latin texts—Virgil, Caesar, Cicero, Seneca, Livy, Cato, and (surprisingly, considering the unmitigated pagan nature of their verse) Ovid, Catullus, and Petronius. And there were the English classics of course—the leather-bound works of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden, Pope, Swift, Samuel Johnson through the Romantics—Wordsworth and Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats and, allegedly Dr. Slade’s favorite, the fated John Clare. The library was designed by the celebrated architect John McComb, Jr., famous for having designed Alexander Hamilton’s Grange: among its features were an ornate coffered ceiling, paneled walls of fifteenth-century tooled leather (reputedly taken from the home of Titian), and portraits of such distinguished Slade ancestors as General Elias Slade, the Reverend Azariah Slade, and the Reverend Jonathan Edwards (related by marriage to the original Slade family)—each rendered powerfully by John Singleton Copley. Portraits, daguerreotypes, and shadow drawings of Dr. Slade’s sons Augustus and Copplestone, and his grandchildren Josiah, Annabel, Todd, and little Oriana, also hung on the wall, just behind Dr. Slade’s desk; and should be mentioned here since all but the child Oriana will figure prominently in this chronicle.

(Is this unobtrusively done? I am a historian, and not a literary stylist; so must “intercalate” such details very consciously, that the reader will take note of them; yet not so obtrusively, that the sensitive reader is offended by over-explicitness.)

In this gracious room, commanding a position of prominence, was a fireplace of stately proportions in whose marble mantel was carved, in Gothic letters, HIC HABITAT FELICITAS—which caught Woodrow’s eye, as always it did when he visited Winslow Slade. With a morose smile Woodrow leaned over to run his fingertips over the chiseled inscription, saying, “Here, Dr. Slade, I have no doubt that happiness abides; but at my home, and in the president’s office in Nassau Hall—not likely.”

During the conversation to follow, the fire in the fireplace blazed and waned; and blazed again, and again waned; until, without either man noticing, the logs collapsed in a crumbling of smoldering coals, like distant, dying suns, into darkness and oblivion which not even a belated poker-stirring, by the younger man, could revive.

AT THIS TIME, before the terrible incursions of the Curse would prematurely age him, Winslow Slade, partly retired from his longtime pastorship at the First Presbyterian Church of Princeton, was a vigorous gentleman of seventy-four, who looked at least a decade younger; as his visitor, not yet fifty, yet looked, with such strain in his face, and his eyes shadowed in the firelight, at least a decade older than his age.

Since the death of his second wife Tabitha some years before, Dr. Slade had remained a widower, and took what melancholy joy he could largely from his several grandchildren.

Though fallen now into quasi-oblivion, known only to historians of the era, Winslow Slade was, in the early years of the twentieth century, one of New Jersey’s most prominent citizens, who had served as a distinguished president of Princeton University, three decades before, in the troubled aftermath of the Civil War and into the early years of Reconstruction, when the academic state of the school was threatened, and Dr. Slade had brought some measure of academic excellence and discipline into the school; and, in the late 1880s, when Dr. Slade had served a term as governor of New Jersey, in a particularly tumultuous and partisan era in which a gentleman of Dr. Slade’s qualities, by nature congenial, inclined rather more to compromise than to fight, and in every way a Christian, found “politics” far too stressful to wish to run for a second term. In Princeton, a far more civilized community than the state capitol in Trenton, Winslow Slade was generally revered as a much-beloved pastor of the Presbyterian church and community leader; and how much more so, than Woodrow Wilson could ever hope to be!