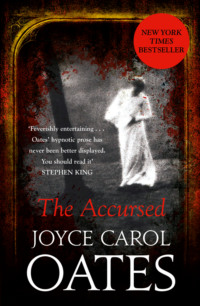

The Accursed

Not that the younger man was jealous of the elder: he was not. But, quite consciously, he wished to learn from the elder.

Though very likely Winslow Slade knew a good deal of the animosity blooming between the university president and his most powerful dean, being the beneficiary of his wife’s network of local news, yet Winslow tactfully asked his young friend if it was a faculty matter, that was troubling him?—or, an undergraduate issue?

Woodrow’s reply was reluctantly uttered: “No, Dr. Slade. I think that I have won the boys over, after some initial coolness—they like me now. This generation is more concerned with making their own worldly way than I would wish, but we understand each other.” Half-consciously Woodrow rose to his feet, to pick up, from Winslow Slade’s desk, a brass letter-opener, and to turn it in his fingers. A thin smile distended his lips. “The mischief of boys I would welcome, Dr. Slade, at this point—if it could spare me this other.”

“ ‘This other’—?”

For an unsettling moment Woodrow lost the thread of his concentration: he was hearing a muted yet vehement voice daring to accuse him. The horror of lynching is, no one speaks against it. Behind the silvery glint of his glasses his eyes filled with tears of vexation. The little brass letter-opener slipped from his fingers to fall onto Winslow Slade’s desk. He said, “I’m speaking of—of certain underhanded challenges to my authority—as president of our university. You know, Dr. Slade, I take my responsibility to be—well, God-ordained; certainly I would not have had this exceptional honor bestowed upon me, if God had not wished it. And so, I am baffled by the calculated insults, malicious backbiting, and plotting among my administrative colleagues—and their secret liaisons with the trustees. Surely by now you’ve heard how my enemies conspire against me in skirmishes that have not the dignity of battle, still less of declared war.”

There followed an embarrassed silence. The elder man, regarding his friend with grave sympathy, could not think how to reply. It was kept fairly secret among Woodrow Wilson’s family and intimates that he had already suffered several mysterious collapses in his lifetime, the earliest as a young adolescent; Woodrow had even had a “mild” stroke at the premature age of thirty-nine. (At the time, Woodrow had been teaching jurisprudence at Princeton, preparing his lectures with great urgency and intensity, and working on the multivolume A History of the American People that would one day solidify his reputation.) Now, a decade later, Woodrow’s nerves were so keenly strung, he seemed at times to resemble a puppet jerked about by cruel, whimsical fingers. Yet, like any sensitive, proud man, he shrank from being comforted.

With a wry smile Woodrow confessed to his friend that, as pressure on him lately increased, he suffered from such darting pains in his head and abdomen as he lay sleepless through much of the night, he half wondered if his enemies—(“Led by that careerist whose name I do not care to speak”)—were devouring his very soul, as a sinister species of giant water spider sucks the life out of its helpless frog prey.

Winslow responded with a wincing smile, “Woodrow, my dear friend, I wish I could banish from your vocabulary such words as battle, war, enemy—even, perhaps, soul. For your nature is to take a little too seriously matters that are only local and transient, and you see conspiracy where there may be little more than a healthy difference of opinion.”

Woodrow stared at his elder friend with a look of hurt and alarm.

“ ‘Healthy difference of opinion’—? I don’t understand, Winslow. This is life or death—my life or death, as president of the university.”

“When the issue is whether to build the new Graduate College at the heart of the campus or, as Dean West prefers, at the edge? That is a matter of your life or death?”

“Yes! Yes, it is. And the eating clubs as well—my enemies are massing against me, to defeat my plan of colleges within the university, of a democratic nature. You know, I believe that the highest executive office must centralize power—whether the chief executive is the President of the United States, or of a distinguished university. And right here at home, I am met with mutiny.”

“Woodrow, really! ‘Mutiny.’ ” Winslow Slade smiled.

“Mutiny, yes,” Woodrow repeated grimly, “and I have no doubt that they are meeting in secret at this very minute, somewhere close by.”

For Woodrow had learned, from a remark of Mrs. Wilson’s when she’d returned from a luncheon at the Princeton Women’s Club two days before, that Andrew Fleming West was to be a houseguest at a dinner party at the home of the Burrs, of FitzRandolph Place, to which the Wilsons had conspicuously not been invited.

Winslow Slade murmured that none of this boded well for the university, if it was true; still less for Woodrow and his family.

“Dr. Slade, it is true,” Woodrow said irritably, “the prediction around town that I will be ‘outflanked’ by Easter, cornered like a rat and made to resign the presidency! Please don’t deny it, sir, in the interests of kindness or charity, for I know very well that Princeton whispers of nothing else—even the washerwomen, and the Negro servants, and every sort of local riffraff, gloat over my distress.”

At this, Winslow Slade leaned over to touch the younger man’s tensed arm. “Tommy—d’you mind if I call you ‘Tommy’?—I hope you remember the advice I gave you, when you accepted the trustees’ offer of the presidency: ‘A wise administrator never admits to having enemies, and a yet wiser administrator never has enemies.’ ”

“A banal platitude, sir, if I may say so,” Woodrow said, with increasing vexation, “—that might have been put to the ‘enemies’ of Napoleon, as his armies swept over them and devastated them utterly. It is easy for you to think in such a way—you who have never known an enemy in your life, and have been blessed by God in all your efforts.”

“I had political enemies enough, when I was governor of the state,” Winslow said. “I think you are forgetting the vicissitudes of real life, in your airy allegorical dramas.”

Woodrow, pacing in front of the fireplace, spoke now rapidly, and heedlessly—saying that Ellen and his daughters were “sick with worry” over his health; his doctor, Melrick Hatch, had warned him that the palliative medications he’d been taking for years to steady his nerves might soon have a “reverse” effect. (One of Woodrow’s medications was the morphine-laced Mrs. Wycroff’s Soothing Syrup; another, McCormick’s Glyco-Heroin Throat Lozenges; yet another, Boehringer & Soehne’s Antiseptique, with its high quotient of opium. Woodrow was also somewhat addicted to such home remedies as syrupy calomel, bismuth, and Oil of Olmay; cascara sagrada and Tidwell’s Purge.) Again, Woodrow picked up the brass letter-opener, to turn it restlessly in his fingers—“The dean, it’s said, boasts that he intends to drive me into an ‘early grave’ and take my place as president. And a majority of the trustees align themselves with him.”

“Woodrow, please! This isn’t worthy of you. I think that you and Dean West must meet face to face, and stop this absurd plotting. I would guess that Andrew goes about Princeton complaining of you, and declaring that you should drive him to an early grave, if you had your way.”

Woodrow stiffened at this remark. For indeed, it had frequently come to him, even when he knelt in prayer at Sunday church services, feeling himself an empty vessel to be filled with the grace of God, that, if something would happen to his enemy Andrew Fleming West: how easy then, his life would become!

“All opposition to my ideas would evaporate at once, like harmless smoke. All opposition.”

“Woodrow, what do you mean? What have you said?”

Had Woodrow spoken aloud? He was sure he had not.

Winslow Slade said, quietly, yet with feeling, “Sometimes I think you scarcely know me, Tommy. Or, indeed—anyone. You so surround yourself with fantasies of your own creation! For instance, you claim that I seem not to have known an enemy in my career, and that God has ‘blessed’ my efforts; but you must know, this was hardly the case. There was a very vocal opposition at the university, when I pushed forward my ‘reform’ of the curriculum, and insisted upon higher admissions standards; very nearly, a revolt among the trustees. And then, when I was governor of this contentious, politician-ridden state, there were days when I felt like a battered war veteran, and only the solace of my religion, and my church, kept me from despair. Yet, I tried not to complain, even to my dear Oriana; I tried never to make careless public remarks, or denunciations. This is not in keeping with our dignity. Remember the doomed Socrates of The Crito—a public man in his seventies condemned to death by the state: it was Socrates’ position that one abides by the laws of his time and place, and that death is preferable to banishment from society. So I’ve long kept my own counsel, and not even those closest to me have known of my secret struggles. So it is, dear Tommy, in the waning years of my life, I can’t allow myself to be drawn into ‘politics’ yet again. I know that your office is a sacred trust in your eyes, very like that of the pulpit; you are your father’s son, in many ways; and you have been driving yourself these past months with a superhuman energy. But it must be remembered, Woodrow, the university is not the church; and your inauguration, however splendid, should not be interpreted as an ordination.” Winslow paused, to allow his words to sink in. It was a misunderstanding of the elder Slade, that he was without sarcasm or irony, as he was without guile; that, being by nature good-hearted and generous, he was one to suffer fools gladly. “So, my counsel to you is compromise, President Wilson—compromise.”

Woodrow reacted like a child who has been slapped. Slowly, dazedly, he sank into his chair by the fireplace, facing his host. Waning firelight played on his tight, taut features; his stricken eyes were hidden behind the wink of his eyeglasses. In a hoarse voice he said: “Compromise!—what a thing to suggest! What—weakness, cowardice! Did our Savior compromise? Did He make a deal with his enemies? My father instructed me, either one is right, and compelled to act upon it; or one is in error, and should surrender the chalice to another man. Jesus declared, ‘I bring not peace but a sword.’ Does not our Lord declare everywhere in His holy writ, that one must be either for Him or against Him? I have reason to believe that all evil begins in compromise, Dr. Slade. Our great President Lincoln did not compromise with the slavers, as our Puritan ancestors did not compromise with the native Indians whom they discovered in the New World, pagan creatures who were not to be trusted—‘drasty Sauvages’ they were called. You might not know, Winslow, but our Wilson family motto—from the time of the Campbells of Argyll until now—God save us from compromise.”

When Winslow didn’t reply, only just shook his head, with an inscrutable expression, Woodrow said, a little sharply: “Ours is a proud heritage! And it would go hard against my father, as against my own conscience, if I weakened in this struggle.”

Winslow said, gently, “But after all, Tommy, you are not your father, however much you love and honor his memory. And you must bear in mind that he is no longer living; he has been dead this past year, and more.”

At these words the younger man stared into a corner of the room as if he had been taken by surprise: was his father dead?

And something else, someone else, another tormenting voice, had been beating at his thoughts, like buffeting waves—You can speak out against these atrocities. Christians like yourself.

Clumsily Woodrow removed his eyeglasses. His vision had never been strong; as a child, letters and numerals had “danced” in his head, making it very difficult for him to read and do arithmetic; yet, he had persevered, and had made of himself an outstanding student, as he was, in his youth, invariably the outstanding member of any class, any school, any group in which he found himself. Destined for greatness. But you must practice humility, not pride.

Woodrow wiped at his eyes with his shirt cuff, in manner and in expression very like a child. It seemed to be so, he did not recall that Joseph Ruggles Wilson, his father, had passed away; into the mysterious other world, into which his mother had passed away when Woodrow had been thirty-two, and his first daughter Margaret had been recently born. “You are right, Winslow—of course. Father has been dead more than two years. He has been gathered into the ‘Great Dark’—abiding now with his Creator, as we are told. Do you think that it is a realm of being contiguous with our own, if inaccessible? Or—is it accessible? I am intrigued by these ‘spiritualists’—I’ve been reading of their exploits, in London and Boston . . . Often I think, though Father is said to be deceased, is he entirely departed? Requiescat in pace. But—is he in peace? Are any of the dead departed—or in peace? Or do we only wish them so, that we can imagine ourselves free of their dominion?”

To which query Winslow Slade, staring into the now-waning fire, as shadows rippled across his face, seemed to have no ready reply.

REQUIESCAT IN PACE is the simple legend chiseled beneath the name winslow elias slade and the dates 14 december 1831–1 june 1906 on the Slade family mausoleum in the older part of the Princeton Cemetery, near the very heart of Princeton. It was said that the distressed gentleman, shortly before his death, left instructions with his family that he wished the somber inscription Pain Was My Portion would be engraved on his tomb; but that his son Augustus forbade it.

“We have had enough of pain, we Slades,” Augustus allegedly declared, “and now we are prepared for peace.”

This was at a time when the Crosswicks Curse, or, as it is sometimes called, the Crosswicks Horror, had at last lifted from Princeton, and peace of a kind had been restored.

I realize, the reader may be wondering: how could Reverend Winslow Slade, so beloved and revered a Princeton citizen, the only man from whom Woodrow Wilson sought advice and solace, have come to so despairing an end? How is this possible?

All I have are the myriad facts I have been able to unearth and assemble, that point to a plausible explanation: the reader will have to draw his or her own conclusions, perhaps.

At the time of our present narrative in March 1905, when Woodrow Wilson sought him out surreptitiously, Winslow Slade retained much of his commanding presence—that blend of authority, manly dignity, compassion, and Christian forbearance noted by his many admirers. No doubt these qualities were inherited with his blood: for Winslow’s ancestry may be traced on his father’s side to those religiously persecuted and religiously driven Puritans who sought freedom from the tyranny of the Church of England in the late 1600s; and on his mother’s side, to Scots-English immigrants in the early 1700s to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who soon acquired a measure of affluence through trade with England. Within two generations, a number of Slades had migrated from New England to the Philadelphia / Trenton area, as, in religious terms, they had migrated from the rigidity of belief of old-style Puritanism to the somewhat more liberal Presbyterianism of the day, tinged with Calvinist determinism as it was; these were compassionate Christians who sided with those who opposed the execution of Quakers as heretics, a Puritan obsession. Sometime later, in the Battle of Princeton of 1777, General Elias Slade famously distinguished himself, alongside his compatriot Lieutenant Colonel Aaron Burr, Jr. (Elias Slade, only thirty-two at the time of his death, had boldly surrendered his powerful positions in both the Royal Governor’s Council and the Supreme Court of the Crown Colony in order to support George Washington in the revolutionary movement—a rebellion by no means so clear-cut in the 1770s nor so seemingly inevitable as it appears to us today in our history textbooks. And what an irony it is that Aaron Burr, Jr., a hero in some quarters in his own time, has been relegated to a disreputable position scarcely more elevated than that of his former compatriot Benedict Arnold!)

It was a general characteristic of the Philadelphia / Trenton branch of the Slade family, judging by their portraits, that the men possessed unusually intense eyes, though deep-set in their sculpted-looking faces; the Slade nose tended to be long, narrow, Roman and somewhat pinched at the tip. In his youth and well into old age, Winslow Slade was considered a handsome man: above average in height, with a head of prematurely silver hair, and straight dark brows, and a studied and somber manner enlivened by a ready and sympathetic smile—in the eyes of some detractors, a too-ready and too-sympathetic smile.

For it was Winslow Slade’s eccentric notion, he would try to embody Christian behavior in his daily—hourly!—life. In this, he often tried the patience of those close to him, still more, those who were associated with him professionally.

“It’s my considered belief that the present age will compose, through Winslow Slade, its spiritual autobiography”—so the famed Reverend Henry Ward Beecher declared on the occasion of Winslow Slade’s inauguration as president of Princeton University in 1877.

As a popular Presbyterian minister, who had studied at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Winslow Slade had long perfected the art of pleasing—indeed, mesmerizing large audiences.

Though, in contrast to such preachers as Reverend Beecher, Winslow Slade never stooped to rhetorical tricks or empty oratorical flourishes. His Biblical texts were usually familiar ones, though not simple; he chose not to astonish, or perplex, or amuse, or, like some men of the cloth, including his formidable relative Jonathan Edwards, to terrify his congregation. His quiet message of the uniqueness of the Christian faith—as it is a “necessary outgrowth and advancement of the Jewish faith”—is that the Christian must think of himself as choosing Jesus Christ over Satan at every moment; an inheritance from his Puritan ancestors, but rendered in such a way as not to alarm or affright his sensitive followers.

It is no surprise that Reverend Slade’s grandchildren, when very young, imagined that he was God Himself—delivering his sermons in the chaste white interior of the First Presbyterian Church on Nassau Street. These were Josiah, Annabel, and Todd; and, in time, little Oriana; when these children shut their eyes in prayer, it was Grandfather Winslow’s face they saw, and Grandfather Slade to whom they appealed.

As The Accursed is a chronicle of, mostly, the Slade grandchildren, it seems fitting for the historian to note that Winslow Slade loved these children fiercely, rather more, it seems, than he had loved his own children, who had been born when Winslow was deeply engaged in his career, and not so deeply engaged with family life, like many another successful public man. While recovering from a bout of influenza in his early sixties, watching Josiah and Annabel frolic together for hours in the garden at Crosswicks Manse, he had declared to his doctor that it was these children, and no other remedy, that had brought him back to health.

“The innocence of such children doesn’t answer our deepest questions about this vale of tears to which we are condemned, but it helps to dispel them. That is the secret of family life.”

“AND HOW IS your daughter Jessie?”

“Jessie? Why—Jessie is well, I think.”

Woodrow’s eighteen-year-old daughter, the prettiest of the Wilson daughters, was to be a bridesmaid in the wedding of Winslow Slade’s granddaughter Annabel and a young U.S. Army lieutenant named Dabney Bayard, of the Hodge Road Bayards.

Winslow had thought to divert his young friend from the thoughts that so agitated him, that seemed, to Winslow, but trivial and transient; but this new subject, unexpectedly, caused Woodrow to fret and frown; and to say, in a very careful voice, “It is always a—a surprise—to me—that my girls are growing into—women. For it seems only yesterday, they were the most delightful little girls.”

Woodrow spoke gravely, with a just perceptible frisson of dread.

For the intimate lives of females was a painful subject for a man of his sensitivity to consider, even at a little distance.

Winslow smiled, however, with grandfatherly affection. For it was the more remarkable to him, his “fairy child” Annabel was now nineteen years old, and about to take her place in society as Mrs. Dabney Bayard.

“Ah, Lieutenant Bayard!—I think I’ve glimpsed the young man once or twice,” Woodrow said, without the slightest edge of reproach in that, perhaps, his wife and he had been excluded from recent social occasions at Crosswicks Manse, “and he seems to me an upstanding Christian youth, and a patriot as well: the grandson, isn’t he, of John Wilmington Bayard?—hearty Presbyterian stock, and most reliable.”

“We shall see. I mean—yes of course. You are quite right.”

More than once, Winslow Slade had caught an unwanted glimpse of his dear granddaughter walking in the garden behind the Manse, with Lieutenant Bayard; a handsome boy, but impetuous, whose hands too frequently made their way onto Annabel’s petite body, at her waist, or lower, at her slender hips . . . It was not a vision the seventy-four-year-old wished to summon, at this awkward time.

Woodrow said, yet still gravely, “Our Margaret, you know, was born in Georgia—not in the North. My dear Ellen took it into her head, near the very end of her pregnancy, that she could not bear for our firstborn to be delivered north of the Mason-Dixon line, and so I—I humored her of course . . . And I think that, in a way, it has made a difference—Margaret is our most gracious daughter, not nearly so—emphatic—headstrong—as the younger girls, born here in the North.”

Winslow Slade, whose ancestors did not hail from the American South, but rather from the Puritan north of New England, tactfully made no reply to this peculiar remark, in its way both apologetic and boastful.

“Would you like a cigar, Tommy? I know that you don’t ‘smoke’—at home, certainly. But I have here some very fine Cuban cigars, given to me by a friend.”

“Thank you, Winslow—but no! I think that I have told you, how my dear mother cured me forever of a wish to smoke?”

Winslow Slade inclined his head politely, that Woodrow might again tell this favorite story. For Woodrow was quite practiced at the recitation of certain family tales, as if they were old tales of Aesop.

“I was seven years old when Mother called me, to enlist her in killing the aphids on her roses. It might have been that I had been watching my father and other male relatives smoking cigars, and may have appeared admiring; Mother was quick to take note of such details, and I have inherited her skill. ‘Tommy, come here: I will light one of Father’s cigars, and you will blow smoke on the nasty aphids.’ And so—that is exactly what I did, or tried to do.” Woodrow was laughing, a wheezing sort of laugh, without evident mirth; tears shone in his eyes, of a frantic merriment. “Ah, I was so ill! Violently ill to my stomach, not only repelled by the horrific tobacco smoke, but vomiting for much of a day. And yet, Mother’s wisdom was such: I have never smoked since, nor have I had the slightest inclination. Observing the trustees lighting up their ill-smelling cigars, when we are meant to have a serious meeting, leaves me quite disgusted, though I would never betray my feelings of course.”

“A most thoughtful mother!” Winslow returned the cigars to their brass humidor.

In a corner of Dr. Slade’s library an eighteenth-century German grandfather’s clock chimed a quiet but unmistakable quarter-hour: Winslow Slade was hoping that his young friend would depart soon, for Woodrow was clearly in one of his “nerve” states, and the effect upon Winslow himself was beginning to be felt; of all psychic conditions, anxiety verging upon paranoia/hysteria is perhaps the most contagious, even among men. Yet, Woodrow could not resist reverting to his subject, in an indirect way, to lament that the United States was burdened with “an insufferable buffoon” in the White House: “A self-appointed bully who fancies himself a savior, mucking about now shockingly in Panama, and swaying the jingoists to his side. The presidency of the United States is not an office to be besmirched but to be elevated—it is a sacred trust, for our nation is exceptional in the history of the world. And I, here at home, in ‘idyllic’ Princeton, must contend with Teddy Roosevelt’s twin, as it were—who pretends only to have the interest of the university at heart, while wresting my power from me.”