Ripper

They were so caught up in the moment that the sun had already begun to set when Indiana realized that she was going to miss the ferry back to San Francisco. She jumped to her feet and said good-bye, but Ryan, explaining that his van was just outside the park, offered to give her a ride—after all, they lived in the same city. The van had a souped-up engine, oversize wheels, a roof rack, a bicycle rack, and a tasseled pink velvet cushion for Attila that neither Ryan nor his dog had chosen—Ryan’s girlfriend Jennifer Yang had given it to him in a fit of Chinese humor.

Three days later, unable to get Indiana out of his mind, Ryan turned up at the Holistic Clinic just to see the woman with the bicycle. She was the polar opposite of the usual subjects of his fantasies: he preferred slim Asian women like Jennifer Yang, who besides having perfect features—ivory skin, silken hair, and a bone structure to die for—was also a high-powered banker. Indiana, on the other hand, was a big-boned, curvaceous, good-hearted typical American girl of the type that usually bored him. Yet for some inexplicable reason he found her irresistible. “Creamy and delicious” was how he described her to Pedro Alarcón, adjectives more appropriate to high-cholesterol food, as his friend pointed out. Shortly after Ryan introduced them, Alarcón commented that Indiana, with her ample diva’s bosom, her blond mane, her sinuous curves and long lashes, had the larger-than-life sexiness of a gangster’s moll from a 1970s movie, but Ryan didn’t know anything about the goddesses who’d graced the silver screen before he was born.

Ryan was somewhat surprised by the Holistic Clinic—having expected a sort of Buddhist temple, he found himself standing in front of a hideous three-story building the color of guacamole. He didn’t know that it had been built in 1940 and for years attracted tourists who flocked to admire its art-deco style and its stained-glass windows, inspired by Gustav Klimt, but that in the earthquake of 1989 its magnificent facade had collapsed. Two of the windows had been smashed, and the remaining two had since been auctioned off, to be replaced with those tinted glass windows the color of chicken shit favored by button factories and military barracks. Meanwhile, during one of the building’s many misguided renovations, the geometric black-and-white-tiled floor had been replaced with linoleum, since it was easier to clean. The decorative green granite pillars imported from India and the tall lacquered double doors had been sold to a Thai restaurant. All that remained of the clinic’s former glory was the wrought-iron banister on the stairs and two period lamps that, if they had been genuine Lalique, would probably have suffered the same fate as the pillars and the doors. The doorman’s lodge had been bricked up, and twenty feet lopped off the once bright, spacious lobby to build windowless, cavelike offices. But as Ryan arrived that morning, the sun shimmered on the yellow-gold windows, and for a magical half hour the space seemed suspended in amber, the walls dripping caramel and the lobby fleetingly recovering some of its former splendor.

Ryan went up to Treatment Room 8, prepared to agree to any therapy, however bizarre. He half expected to see Indiana decked out like a priestess; instead she greeted him wearing a white coat and a pair of white clogs, her hair pulled back into a ponytail and tied with a scrunchie. There was nothing of the sorceress about her. She got him to fill out a detailed form, then took him back out into the corridor and had him walk up and down to study his gait. Only then did she tell him to strip down to his boxer shorts and lie on the massage table. Having examined him, she discovered that one of his hips was slightly higher than the other, and his spine had a minor curvature—unsurprising in a man with only one leg. In addition she diagnosed an energy blockage in the sacral chakra, knotted shoulder muscles, tension and stiffness in the neck, and an exaggerated startle reflex. In a word, he was still a Navy SEAL.

Indiana assured him that some of her therapies would be helpful, but that if he wanted them to be successful, he had to learn to relax. She recommended acupuncture sessions with Yumiko Sato, two doors down, and without waiting for him to agree, picked up the phone and made an appointment for him with a Qigong master in Chinatown, five blocks from the Holistic Clinic. It was only to humor her that Ryan agreed to these therapies, but in both cases he was pleasantly surprised.

Yumiko Sato, a person of indeterminate age and gender who had close-cropped hair like his own, thick glasses, a dancer’s delicate fingers, and a sepulchral serenity, took his pulse and arrived at the same diagnosis as Indiana. Ryan was advised that acupuncture could be used to treat his physical pain, but it would not heal the wounds in his mind. He flinched, thinking he had misheard. The phrase intrigued him, and some months later, after they had established a bond of trust, he asked Yumiko what she had meant. Yumiko Sato said simply that only fools have no mental wounds.

Ryan’s Qigong lessons with Master Xai—who was originally from Laos and had a beatific face and the belly of a Laughing Buddha—were a revelation: the perfect combination of balance, breathing, movement, and meditation. It was the ideal exercise for body and mind, and Ryan quickly incorporated it into his daily routine.

Indiana didn’t manage to cure the spasms within three weeks as promised, but Ryan lied so he could take her out and pay for dinner, since by then he’d realized that financially she was bordering on poverty. The bustling yet intimate restaurant, the French-influenced Vietnamese food, and the bottle of Flowers pinot noir all played a part in cementing a friendship that in time Ryan would come to think of as his greatest treasure. He had lived his life among men. The fifteen Navy SEALs he’d trained with when he was twenty were his true family; like him they were inured to rigorous physical exertion, to the terror and exhilaration of war, to the tedium of hours spent idle. Some of his comrades, he had not seen in years, others he had seen only a few months earlier, but he kept in touch with them all; they would always be his brothers.

Before he lost his left leg, the navy vet’s relationships with women had been uncomplicated: sexual, sporadic, and so brief that the features of these women blurred into a single face that looked not unlike Jennifer Yang’s. They were usually just flings, and when from time to time he did fall for someone, the relationship never lasted. His life—constantly on the move, constantly fighting to the death—did not lend itself to emotional attachments, much less to marriage and children. He fought a constant war against his enemies, some real, others imaginary; this was how he had spent his youth.

In civilian life Ryan was awkward, a fish out of water. He found it difficult to make small talk, and his long silences sometimes seemed insulting to people who didn’t know him well. The fact that San Francisco was the center of a thriving gay community meant it was teeming with beautiful, available, successful women very different from the girls Ryan was used to encountering in dive bars or hanging around the barracks. In the right light, Ryan could easily pass for handsome, and his disability—aside from giving him the martyred air of a man who has suffered for his country—offered a good excuse to strike up a conversation. He was never short of offers, but when he was with the sort of intelligent woman he found attractive, he worried so much about making a good impression that he ended up boring them. No California woman would rather spend the evening listening to war stories, however heroic, than go clubbing—no one, that is, except Jennifer Yang, who had inherited not only the infinite patience of her ancestors in the Celestial Empire but also the ability to pretend she was listening when actually she was thinking about something else. Yet from the very first time they met among the sequoias in Samuel P. Taylor State Park, Ryan had felt comfortable with Indiana Jackson. A few weeks later, at the Vietnamese restaurant, he realized he didn’t need to rack his brains for things to talk about; half a glass of wine was all it took to loosen Indiana’s tongue. The time flew by, and when he checked his watch, Ryan saw it was past midnight and the only other people in the restaurant were two Mexican waiters clearing tables with the disgruntled air of men who had finished their shift and were anxious to get home. It was on that night, three years ago, that Ryan and Indiana had become firm friends.

For all his initial skepticism, after three or four months the ex-soldier was forced to admit that Indiana was not just some crazy New Age hippie; she genuinely had the gift of healing. Her therapies relaxed him; he slept more soundly, and the cramps and spasms had all but disappeared. But the most wonderful thing about their sessions together was the peace they brought him: her hands radiated affection, and her sympathetic presence stilled the voices from his past.

As for Indiana, she came to rely on this strong, silent friend, who kept her fit by forcing her to jog the endless paths and forest trails in the San Francisco area, and bailed her out when she had financial problems and couldn’t bring herself to approach her father. They got along well, and though the words were never spoken, she sensed that their friendship might have blossomed into a passionate affair if she wasn’t still hung up on her elusive lover Alan, and Ryan wasn’t so determined to push away love in atonement for his sins.

The summer her mother met Ryan Miller, Amanda Martín had been fourteen, though she could have passed for ten. She was a skinny, gawky girl with thick glasses and a retainer who hid from the unbearable noise and glare of the world behind her mop of hair or the hood of her sweatshirt; she looked so unlike her mother that people often asked if she was adopted. From the first, Ryan treated Amanda with the exaggerated courtesy of a Japanese gentleman. He made no effort to help her during their long bike ride to Los Angeles, although, being an experienced triathlete, he had helped her to train and prepare for the trip, something that won him the girl’s trust.

One Friday morning at seven, all three of them—Indiana, Amanda, and Ryan—set off from San Francisco with two thousand other keen cyclists wearing red AIDS awareness ribbons, escorted by a procession of cars and trucks filled with volunteers transporting tents and provisions. They arrived in Los Angeles the following Friday, their butts red-raw, their legs stiff, and their minds as free of thoughts as newborn babes. For seven days they had pedaled up hills and along highways, through stretches of beautiful countryside and others of hellish traffic. To Ryan—for whom a daily fifteen-hour bike ride was a breeze—the ride was effortless, but to mother and daughter it felt like a century of agonizing effort, and they only got to the finish line because Ryan was there, goading them like a drill sergeant whenever they flagged and recharging their energy with electrolyte drinks and energy bars.

Every night, like an exhausted flock of migrating birds, the two thousand cyclists descended on the makeshift campsites erected by the volunteers along the route, wolfed down five thousand calories, checked their bicycles, showered in trailers, and rubbed their calves and thighs with soothing ointment. Before they went to sleep, Ryan applied hot compresses to Indiana and Amanda and gave them little pep talks about the benefits of exercise and fresh air.

“What has any of this got to do with AIDS?” asked Indiana on the third day, having cycled for ten hours, weeping from sheer exhaustion and for all the woes in her life. “What do I know?” was Ryan’s honest answer. “Ask your daughter.”

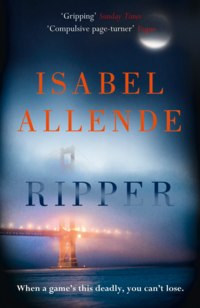

The ride may have made only a modest contribution to the fight against AIDS, but it cemented the budding friendship between Ryan and Indiana, while for Amanda it led to something impossible: a new friend. This girl, who looked set to become a hermit, had precisely three friends in the world: her grandfather, Blake Jackson; Bradley, her future boyfriend; and now Ryan Miller, the Navy SEAL. The kids she played Ripper with didn’t fall into the same category; she only knew them within the context of the game, and their relationship was entirely centered around crime.

Tuesday, 3

Amanda’s godmother, Celeste Roko, the most famous astrologer in California, made her “bloodbath” prediction the last day of September 2011. Her daily show aired early, before the morning weather forecast, and repeated after the evening news. At fiftysomething, thanks to a little nip and tuck, Roko looked good for her age. Charming on screen and a dragon in person, she was considered beautiful and elegant by her many admirers. She looked like Eva Perón with a few extra pounds. The set for her TV show featured a blown-up photo of the Golden Gate Bridge behind a fake picture window and a huge model of the solar system, with planets that could light up and be moved by remote control.

Psychics, astrologers, and other practitioners of the mysterious arts tend to make their predictions on New Year’s Eve, but Madame Roko could not bring herself to wait three months before warning the citizens of San Francisco of the horrors that lay in store for them. Her prophecy was of such magnitude that it captured the public imagination, went viral on the Internet. Her pronouncement provoked scathing editorials in the local press and hysterical headlines in the tabloids, speculating about terrible atrocities at San Quentin State Prison, gang warfare between blacks and Latinos, and an apocalyptic earthquake along the San Andreas Fault. But Celeste Roko, who exuded an air of infallibility thanks to a former career as a Jungian analyst and an impressive number of accurate predictions, was adamant that her vision concerned murders. This provoked a collective sigh of relief among devotees of astrology, since it was the least dreadful of the calamities they had feared. In northern California, the chance of being murdered was one in twenty thousand; it was, everyone believed, a crime that happened to other people.

It was on the day of this prediction that Amanda and her grandfather finally decided to challenge the power of Celeste Roko. They were sick and tired of the influence Amanda’s godmother wielded over the family by pretending that she could foretell the future. Madame Roko was a temperamental woman with the unshakable belief in herself common to those who receive direct messages from the universe or from God. She never managed to sway Blake Jackson, who would have no truck with astrology, but Indiana always consulted Celeste before making important decisions, allowing her life to be guided by the dictates of her horoscope. All too often Celeste Roko’s astrological readings thwarted Amanda’s best-laid plans. When she was younger, for example, the planets had deemed it an inauspicious moment to buy a skateboard but a propitious time to take up ballet—which left Amanda in a pink tutu, sobbing with humiliation.

When she turned thirteen, Amanda discovered that her godmother was not in fact infallible. The planets had apparently decided that Amanda should go to a public high school, but Encarnación Martín, her formidable paternal grandmother, insisted she attend a Catholic boarding school. For once Amanda sided with Celeste, since a co-ed school seemed slightly less terrifying than being taught by nuns. But Doña Encarnación triumphed over Celeste Roko—by producing a check for the tuition fees. Little did she suspect that the nuns would turn out to be feminists in pants who challenged the pope, and used science class to demonstrate the correct use of a condom with the aid of a banana.

Encouraged by the skepticism of her grandfather, who rarely dared to directly challenge Celeste, Amanda questioned the relationship between the heavenly bodies and the fates of human beings; to her, astrology seemed as much mumbo-jumbo as her mother’s white magic. Celeste’s most recent prognostication offered grandfather and granddaughter a perfect opportunity to refute the predictive powers of the stars. It is one thing to announce that the coming week is a favorable one for letter-writing, quite another to predict a bloodbath in San Francisco. That’s not something that happens every day.

When Amanda, her grandfather, and her online buddies transformed Ripper from a game into a criminal investigation, they could never have imagined what they were getting themselves into. Precisely eleven days after Celeste Roko’s pronouncement, Ed Staton was murdered. This might have been considered a coincidence, but given the unusual nature of the crime—the baseball bat—Amanda began to put together a case file using information published in the papers, what little she managed to wheedle out of her father, who was conducting the investigation, and whatever her grandfather could dig up.

Blake Jackson was a pharmacist by profession, a book lover, and a frustrated writer until he finally took the opportunity to chronicle the tumultuous events predicted by Celeste Roko. In his novel, he described his granddaughter Amanda as “idiosyncratic of appearance, timorous of character, but magnificent of mind”—his baroque use of language distinguishing him from his peers. His account of these fateful events would end up being much longer than he expected, even though—excepting a few flashbacks—it spanned a period of only three months. The critics were vicious, dismissing his work as magical realism—a literary style deemed passé—but no one could prove he had distorted the events to make them seem supernatural, since the San Francisco Police Department and the daily newspapers documented them.

In January 2012, Amanda Martín was sixteen and a high school senior. As an only child, Amanda had been dreadfully spoiled, but her grandfather was convinced that when she graduated from high school and went out into the world that would sort itself out. She was vegetarian now only because she didn’t have to cook for herself; when she was forced to do so, she would be less persnickety about her diet. From an early age Amanda had been a passionate reader, with all the dangers such a pastime entails. Although the San Francisco murders would have been committed in any case, Amanda would not have been involved if an obsession with Scandinavian crime novels had not developed into a morbid interest in evil in general and premeditated murder in particular. Though her grandfather was no advocate of censorship, it worried him that Amanda was reading books like this at fourteen. His granddaughter put him in his place by reminding him that he was reading them too, so all Blake Jackson could do was give her a stern warning about their content—which of course made her all the more curious. The fact that Amanda’s father was deputy chief of the homicide detail in San Francisco’s Personal Crimes Division fueled her obsession; through him she discovered how much evil there was in this idyllic city, which could seem immune to it. But if heinous crimes happened in enlightened countries like Sweden and Norway, there was no point in expecting things to be different in San Francisco—a city founded by rapacious prospectors, polygamous preachers, and women of easy virtue, all lured by the gold rush of the mid-nineteenth century.

Amanda went to an all-girls boarding school—one of a handful that still remained since America had opted for the muddle of mixed education—at which she had somehow survived for four years by managing to be invisible to her classmates, although not to the teachers and the few nuns who still worked there. She had an excellent grade-point average, although the sainted sisters never saw her open a textbook and knew she spent most nights staring at her computer, engrossed in mysterious games, or reading unsavory books. They never dared to ask what she was reading so avidly, suspecting that she read the very books they enjoyed in secret. Only the girl’s questionable reading habits could explain her morbid fascination for guns, drugs, poison, autopsies, methods of torture, and means of disposing of dead bodies.

Amanda closed her eyes and took a deep breath of fresh winter-morning air. The smell of pine needles told her that they were driving through the park; the stench of dung, that they were passing the riding stables. Thus she could calculate that it was exactly 8:23 a.m. She had given up wearing a watch two years earlier so she could train herself to tell time instinctively, the same way she calculated temperature and distance; she’d also refined her sense of taste so that she could distinguish suspect ingredients in her food. She cataloged people by scent: her grandfather, Blake, smelled of gentleness—a mixture of wool sweaters and chamomile; Bob, her father, of strength—metal, tobacco, and aftershave; Bradley, her boyfriend, of sensuality, sweat and chlorine; and Ryan smelled of reliability and confidence, a doggy aroma that was the most wonderful fragrance in the world. As for her mother Indiana, steeped in the essential oils of her treatment room, she smelled of magic.

After her grandfather’s spluttering ’95 Ford passed the stables, Amanda mentally counted off three minutes and eighteen seconds, then opened her eyes and saw the school gates. “We’re here,” said Jackson, as though this fact might have escaped her notice. Her grandfather, who kept fit playing squash, took Amanda’s heavy schoolbag and nimbly bounded up to the second floor while she trudged after him, violin in one hand, laptop in the other. The dorm room was deserted: since the new semester did not begin until tomorrow morning, the rest of the boarders would not be back from Christmas vacation until tonight. This was another of Amanda’s manias: wherever she went, she had to be the first to arrive so she could reconnoiter the terrain before potential enemies showed up. Amanda found it irritating to have to share the dorm room with others—their clothes strewn across the floor, their constant racket; the smells of shampoo, nail polish, and stale candy; the girls’ incessant chatter, their lives like some corny soap opera filled with jealousy, gossip, and betrayal from which she felt excluded.

“My dad thinks that Ed Staton’s murder was some sort of gay revenge killing,” Amanda told her grandfather before he left.

“What’s he basing that theory on?”

“On the baseball bat shoved—you know where,” Amanda said, blushing to her roots as she thought of the video she’d seen online.

“Let’s not jump to conclusions, Amanda. There’s still a lot we don’t know.”

“Exactly. Like, how did the killer get in?”

“Ed Staton was supposed to lock the doors and set the alarm when he started his shift,” said Blake. “Since there was no sign of forced entry, we have to assume the killer hid in the school before Staton locked up.”

“But if the murder really was premeditated, why didn’t the guy kill Staton before he drove off? He couldn’t have known Staton intended to come back.”

“Maybe it wasn’t premeditated. Maybe someone sneaked into the school intending to rob the place, and Staton caught him in the act.”

“Dad says that in all the years he’s worked in homicide, though he’s seen murderers who panicked and lashed out violently, he’s never come across a murderer who took the time to hang around and cruelly humiliate his victim.”

“What other pearls of wisdom did Bob come up with?”

“You know what Dad’s like—I have to surgically extract every scrap of information from him. He doesn’t think it’s an appropriate subject for a girl my age. Dad’s a troglodyte.”

“He’s got a point, Amanda. This whole thing is a bit sordid.”

“It’s public domain, it was on TV, and if you think you can handle it, there’s a video on the Internet some little girl shot on her cell phone.”

“Jeez, that’s cold-blooded. Kids these days are so used to violence that nothing scares them. Now, back in my day . . .” Jackson trailed off with a sigh.

“This is your day! It really bugs me when you talk like an old man. So, have you checked out the juvenile detention center, Kabel?”

“I’ve got work to do—I can’t just leave the drugstore unattended. But I’ll get to it as soon as I can.”