Ripper

“It’s just a figure of speech, Danny,” snapped Indiana.

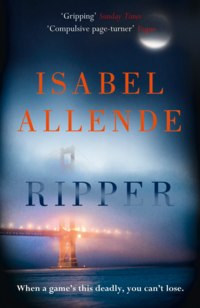

“Just saying, hon, because if she’s thinking of jumping off the Golden Gate, I wouldn’t advise it. They’ve got railings up and CCTV cameras to discourage jumpers. You get bipolars and depressives come from all over the world to throw themselves off that freakin’ bridge, it’s like a tourist attraction. And they always jump in toward the bay—never out to sea, because they’re scared of sharks.”

“Danny!” Indiana yelped, passing Carol a paper napkin to blow her nose.

The waiter wandered off with his tray, but a couple of minutes later he was hovering again, listening to Indiana try to comfort her hapless friend. She gave Carol a ceramic locket to wear around her neck and three dark glass vials containing niaouli, lavender, and mint. She explained that, being natural remedies, essential oils are quickly absorbed through the skin, making them ideal for people who can’t take oral medication. She told Carol to put two drops of niaouli into the locket every day to ward off the nausea, put a few drops of lavender on her pillow, and rub the peppermint oil into the soles of her feet to lift her spirits. Did she know that peppermint oil was rubbed into the testicles of elderly bulls in order to—

“Indi!” Carol interrupted her. “I don’t even what to think about what that must be like! Those poor bulls!”

Just at that moment the great wooden door with its beveled glass panels swung open—it was as ancient and tattered as everything in the Café Rossini—and in stepped Lulu Gardner, making her daily rounds of the neighborhood. Everyone except Carol Underwater immediately recognized the tiny, toothless old woman. Lulu was as wrinkled as a shriveled apple; the tip of her nose almost touched her chin, and she wore a scarlet bonnet and cape like Little Red Riding Hood. She’d lived in North Beach since the long-forgotten era of the beatniks and was the self-professed official photographer of the area. The curious old crone claimed she had been photographing the people of North Beach since the early twentieth century when Italian immigrants flooded in after the 1906 earthquake, not to mention snapping pictures of every famous resident from Jack Kerouac (an able typist, according to Lulu), Allen Ginsberg, her favorite poet and activist, and Joe DiMaggio, who’d lived here in the 1950s with Marilyn Monroe, to the Condor Club Girls—the first strippers to unionize, in the 1970s. Lulu had photographed them all, the saints and the sinners, watched over by the patron saint of the city, Saint Francis of Assisi, from his shrine down on Vallejo Street. She wandered around with a walking stick almost as tall as she was, clutching the sort of Polaroid camera no one makes these days and a huge photo album tucked under one arm.

There were all sorts of rumors about Lulu, and she never took the trouble to deny them. People said that though she looked like a bag lady, she had millions salted away somewhere; that she was a survivor from a concentration camp; that she’d lost her husband at Pearl Harbor. All anyone knew for certain was that Lulu was Jewish—not that this stopped her celebrating Christmas. The previous year Lulu had mysteriously disappeared, and after three weeks the neighbors gave her up for dead and decided to hold a memorial service in her honor. They set up a large photo of Lulu in a prominent place in Washington Park where people came to lay flowers, stuffed toys, reproductions of her photos, meaningful poems, and messages. At dusk the following Sunday, when a dozen people with candles had gathered to pay a reverent last farewell, Lulu Gardner showed up in the park and promptly began to photograph the mourners and ask them who had died. Feeling that she had mocked them, many of the neighbors never forgave her for still being alive.

Now the photographer stepped into the Café Rossini, weaving between the tables like a dancer to the slow blues from the loudspeakers, singing softly and offering her services. She approached Indiana and Carol, gazing at them with her beady, rheumy eyes. Before anyone could stop him, Danny D’Angelo crouched between the women, hunkering down to their level, and Lulu Gardner clicked the shutter. Startled by the flash, Carol Underwater leaped to her feet so suddenly she knocked over her chair. “I don’t want your fucking photos, you old witch!” she yelled, trying to snatch the camera from a terrified Lulu, who backed away as Danny D’Angelo intervened. Astonished by this overreaction, Indiana tried to calm her friend, while a murmur of disapproval rippled through the café’s customers, including some who had been offended by Lulu’s resurrection. Mortified, Carol slumped back into her chair and buried her face in her hands. “My nerves are shot to shit,” she sobbed.

Thursday, 5

Amanda waited for her roommates to grow tired of gossiping about Tom Cruise’s impending divorce and go to sleep before calling her grandfather.

“It’s two a.m., Amanda, you woke me up. Don’t you ever sleep, girl?”

“Sure, in class. You got any news for me?”

“I went and talked with Henrietta Post.” Her grandfather yawned.

“The neighbor who discovered the Constantes’ bodies?”

“That’s her.”

“So why didn’t you call?” his granddaughter chided him. “What were you waiting for?”

“I was waiting for sunup!”

“But it’s been weeks since the murders. You know this all happened back in November, right?”

“Yeah, Amanda, but I couldn’t make it out there any earlier. Don’t worry, the woman remembers everything. Got a shock that scared her half to death, but every last detail of what she saw that day is burned into her brain—the most terrifying day of her life, she told me.”

“So give me the lowdown, Kabel.”

“I can’t. It’s late, and your mom will be home any minute.”

“It’s Thursday—Mom’s with Keller.”

“But she doesn’t always spend the night with him. ’Sides, I need my sleep. I can send you the notes from my conversation with Henrietta Post and what I managed to wheedle out of your father.”

“You wrote it all down?”

“One of these days, I’m going to write a novel,” said her henchman. “I jot down anything that interests me, never know what might be useful to me in the future.”

“Write your memoirs,” suggested his granddaughter. “That’s what most old codgers do.”

“Nah—it would bomb, nothing worth writing about has ever happened to me. I’m the most pitifully boring widower in the world.”

“True. Anyway, send me those notes on the Constantes. G’night, Hench. You love me?”

“Nope.”

“Me neither.”

Minutes later, the details of Blake Jackson’s interview with the key witness to the Constantes murder were in Amanda’s in-box.

On the morning of November 11 at about ten fifteen, Henrietta Post, who lived on the same street as the Constantes, was out walking her dog when she noticed that the door to their place was wide open—something unusual in that neighborhood, where they’d had trouble with gangbangers and drug dealers. Henrietta rang the doorbell, intending to warn the Constantes, whom she knew well, and when no one answered she stepped inside, calling to see if anyone was home. She wandered through the living room, where the TV was blaring, through the dining room and the kitchen, then climbed the stairs—with some difficulty, given that she’s seventy-eight and suffers from palpitations. The resounding silence made her uneasy in a house usually so bustling with life; more than once she’d had to complain about the racket.

She found the children’s bedrooms empty and shuffled down the short passageway to the master bedroom, calling out to the Constantes with what little breath she had left. She knocked three times before opening the door and poking her head in. She says the bedroom was in semi-darkness, with the shutters closed and the curtains drawn, and that it was cold and stuffy in there, as though it hadn’t been aired in days. She took a couple steps into the room, her eyes adjusting to the darkness, then quickly retreated with a mumbled apology when she saw the outline of the couple lying in the bed.

She was about to creep out quietly, but instinct told her there was something strange about the stillness of the house, about the fact that the Constantes had not answered when she called and were sound asleep in the middle of a weekday morning. She crept back into the room, fumbling along the wall for the switch, and flicked on the light. Doris and Michael Constante were lying on their backs with the comforter pulled up to their necks, utterly rigid, their eyes wide open. Henrietta Post let out a strangled cry, felt a heavy jolt in her chest, and thought her heart was about to burst. She couldn’t bring herself to move until she heard her dog barking—then she walked back along the corridor, stumbled down the stairs, and, grasping at the furniture for support, tottered as far as the phone in the kitchen.

She dialed 911 at precisely 10:29; her neighbors were dead, she said over and over, until finally the operator interrupted to ask two or three key questions and tell her to stay right where she was and not touch anything, that help was on its way. Six minutes later two patrol officers who happened to be in the neighborhood showed up, followed almost immediately by an ambulance and police backup. There was nothing the paramedics could do for the Constantes, but they rushed Henrietta Post to the emergency room with tachycardia and blood pressure that was going through the roof.

At about eleven, by which time the street had been taped off, Inspector Bob Martín arrived with Ingrid Dunn, the medical examiner, and a photographer from forensic services. Bob pulled on latex gloves and followed the medical examiner upstairs to the Constantes’ bedroom. On seeing the couple lying in the bed, he initially assumed he was dealing with a double suicide, though he would have to wait for a verdict from Dunn, who was meticulously studying those parts of the bodies that were visible, careful not to move anything. Bob let the photographer get on with his job while the rest of the forensics team showed up; then the ME had the gurneys brought up, and the couple was taken to the morgue. The crime scene might belong to the San Francisco Police Department, but the bodies were hers.

The autopsy later revealed that Doris, forty-seven, and Michael, forty-eight, had both died of an overdose of heroin injected directly into the jugular vein, and that both had had their buttocks branded postmortem.

Ten minutes later the phone woke Blake Jackson again.

“Hey, Hench, I’ve got a question.”

“Amanda, that’s it—I’ve had enough!” roared her grandfather. “I resign as your henchman!”

His words were followed by a deathly silence.

“Amanda?” ventured her grandfather after a second or two.

“Yeah?” she said, her voice quavering.

“I’m just kidding. What did you want to ask?”

“Tell me about the burn marks on their butts.”

“They were discovered at the morgue when the bodies were stripped,” her grandfather said. “I forgot to mention in my notes that they found a couple of used syringes with traces of heroin on them in the bathroom, along with a butane blowtorch that was almost certainly used to make the burns. All of it wiped clean of prints.”

“And you’re saying this just slipped your mind?! That’s vital evidence!”

“I meant to put it in, but I got sidetracked. I figure that stuff was left there on purpose, as a taunt—all neatly set out on a tray and covered with a white napkin.”

“Thanks, Kabel.”

“ ’Night, boss.”

“ ’Night, Grandpa. I won’t call again, promise. Sleep tight.”

It was one of those nights with Alan that Indiana looked forward to like a blushing bride, although they had long since established a routine in which there were few surprises, and the rhythms of their sex life were those of an old married couple. They had been together for four years: they were an old married couple. They knew each other intimately, loved each other in a leisurely fashion, and took the time to laugh, to eat, to talk. Alan would have said they made love sedately, like a couple of geriatrics; Indiana felt that for geriatrics they were pretty debauched. They were happy with the arrangement—early on they had tried out some porn-movie acrobatics that had left Indiana peeved and Alan half paralyzed; they had explored more or less everything a healthy imagination could dream up without involving third parties or animals, and had finally settled on a repertoire of four conventional positions with some variations, which they acted out at the Fairmont Hotel once or twice a week as their bodies demanded.

While they waited for the oysters and smoked salmon they had ordered from room service, Indiana recounted the tragic tale of Carol Underwater, and told Alan about Danny D’Angelo’s tactless comments. Alan knew Danny, and not only because he often met Indiana at the Café Rossini. A year ago Danny had flamboyantly thrown up in Alan’s new Lexus while Alan—at Indi’s request—was driving him to the emergency room. He’d had to have the car washed several times to get rid of the stains and the stench.

It had happened that June, after the city’s annual Gay Pride March, during which Danny had disappeared. He didn’t come in to work the next day, and no one heard from him until six days later, when some guy with a Hispanic accent phoned to tell Indiana that her friend was in a bad way, ill and alone in his apartment, and to suggest she go round and look after him, or he could wind up dead. Danny lived in a crumbling building in the Tenderloin, where even the police were afraid to venture after dark, a neighborhood characterized by booze, drugs, brothels, and shady nightclubs that had always attracted drifters and delinquents. “The throbbing heart of Sin City,” Danny called it with a certain pride, as though those living there deserved a medal for bravery. His apartment block had been built in the 1940s for sailors, but over time it had degenerated into a refuge for the destitute, the drugged-up, and the diseased. More than once Indiana had come by to bring food and medication to her friend, who often ended up a wreck after some sleazy binge.

When she got the anonymous call, Indiana once again rushed to Danny’s side. She climbed the five flights of stairs scrawled with graffiti, four-letter words, and obscene drawings, past the seedy apartments of drunkards, doddering lunatics, and rent boys who turned tricks for drugs. Danny’s room was dark and stank of vomit and patchouli oil. There was a bed in one corner, a closet, an ironing board, and a quaint little dressing table with a satin valance, a cracked mirror, and a vast collection of makeup jars. There were a dozen pairs of stilettos and two clothes racks from which the feathery sequined dresses Danny wore as a cabaret singer hung like ugly, lifeless birds. There was little natural light; the only window was caked with twenty years’ worth of grime.

Indiana found Danny sprawled on the bed, filthy and still half dressed in the French maid’s outfit he had worn to Gay Pride. He was burning up and severely dehydrated, a combination of pneumonia and the lethal cocktail of alcohol and drugs he had ingested. Each floor of the building had only one bathroom shared by twenty tenants, and Danny was too weak for Indiana to drag him there. He didn’t respond when Indiana tried to get him to sit up, drink some water, and clean himself up. Realizing she could not deal with him on her own, she called Alan.

Alan was bitterly disappointed to realize Indiana had called him only as a last resort. Her father’s car was in the shop, probably, and that son of a bitch Ryan Miller was off traveling somewhere. The tacit agreement whereby their relationship was limited to a series of romantic encounters suited him, but it somehow offended him to realize that Indiana could happily exist without him. Indiana was constantly broke—a fact she never mentioned—but whenever he offered help, she dismissed the idea with a laugh. Instead she turned to her father for help, and—though he had no proof—Alan was convinced she was prepared to accept help from Miller. “I’m your lover, not some kept woman,” Indiana would say whenever he offered to pay the rent on her consulting rooms or Amanda’s dentist’s bill. He’d wanted to buy her a Volkswagen Beetle for her birthday—a lemon-yellow one, or maybe that deep nail-polish red she loved—but Indiana dismissed the idea: public transport and her bicycle were more environmentally friendly. She refused to allow him to open a bank account in her name or give her a credit card, and she didn’t like it when he gave her clothes, thinking—rightly—that he was trying to make her over. Indiana found the expensive silk and lace lingerie he bought for her faintly ridiculous, but to make him happy she wore it as part of their erotic games. Alan knew that the moment his back was turned, she would give it to Danny, who probably appreciated it more.

Although Alan admired Indiana’s integrity, he was upset that she did not seem to need him. Being with this woman who was happier to give than to receive made him feel small, made him feel cheap. In all their years together, she had rarely asked for his help, so when she called from Danny’s apartment, he rushed to her side.

The Tenderloin district was notorious for Filipino, Chinese, and Vietnamese gangs, for robbery, assault, and murder; Alan had hardly ever set foot there, even though it was in the heart of San Francisco, only a few blocks from the banks, stores, and expensive restaurants he frequented. He still harbored a romantic, antiquated notion of the district: to him it was 1920 there, and the place was still full of gambling dens, speakeasies, boxing rings, brothels, and sundry other lowlife. He vaguely remembered that Dashiell Hammett had set one of his novels in the Tenderloin—maybe The Maltese Falcon. He did not realize that after the Vietnam War, the area had been flooded with Asian refugees drawn by cheap rents and the proximity to Chinatown; that nowadays up to ten people lived in the one-bedroom apartments. Seeing the hobos sprawled on the sidewalk with their sleeping bags and their overstuffed shopping carts, the shifty men hovering on street corners, and the toothless, disheveled women muttering to themselves, Alan realized it was probably best not to park on the street.

It took him a while to find a secure parking lot, and longer still to find Danny’s building; the street numbers had been worn away by time and weather, and he could not bring himself to ask for directions. When he finally did stumble on the place, it was even seedier and more run-down than he had expected. Drunks, drifters, and shady-looking guys lurked in the doorways or shambled along the hallways, and he worried that some thug might jump him. He walked faster, careful to look no one in the eye, suppressing the urge to hold his nose, acutely aware of how ridiculous his Italian suede shoes and his Barbour jacket must look in a place like this. The five-floor climb up to Danny’s room seemed fraught with danger, and when he finally got there, the reek of vomit stopped him in the doorway.

By the light of the bare bulb dangling from the ceiling he could see Indiana leaning over the bed, washing Danny’s face with a damp cloth. “We have to get him to the hospital, Alan,” she said quickly. “I need you to put a shirt and some pants on him.” Alan felt his throat heave and had the urge to retch, but he could not be a coward and give up, not now. Careful not to get dirty, he helped Indiana to wash and dress the delirious man. Danny was skinny, but in his present state he seemed heavy as a horse. Between them they managed to get Danny on his feet and half carried, half dragged him along the hallway to the stairwell, then step by step down to the ground floor to sneering looks from the other tenants. Outside, they sat Danny down on the sidewalk between a couple of garbage cans, and Indiana stayed with him while Alan ran the few blocks to his car. It was while Danny was spraying the backseat of the gold Lexus with vomit that it occurred to Alan they could have called an ambulance. This thought had not even crossed Indiana’s mind; calling an ambulance would cost a thousand dollars, and Danny had no medical insurance.

Danny D’Angelo spent a week in the hospital while doctors struggled to get his pneumonia, stomach infection, and blood pressure under control. Then he spent a second week staying with Indiana’s father, who reluctantly played nursemaid until Danny was strong enough to manage on his own and go back to his rathole and his job. Blake Jackson barely knew Danny D’Angelo at the time, but he collected the man from the hospital because his daughter asked him to, and gave him a bed and took care of him for the same reason.

Alan Keller had first been attracted by Indiana Jackson’s looks: a healthy, well-fed mermaid. Later he was captivated by her optimistic personality; in fact, he liked her precisely because she was the polar opposite of the skinny, neurotic women he usually dated. He would never have admitted that he was “in love”—that would be tasteless, he felt no need to put a name on what he felt. It was enough that he enjoyed the carefully prearranged, slightly predictable times they spent together. During the weekly sessions with his analyst, who, like most therapists in California, was a New York Jew and a practicing Zen Buddhist, Alan had acknowledged that he was “very fond” of Indiana, a euphemism that allowed him to avoid using the word passion, something he appreciated only in opera, where violent emotions shaped the destinies of tenor and soprano. Indiana’s beauty inspired in him an aesthetic pleasure more constant than sexual desire, her freshness moved him, and her admiration for him had become an addictive drug he would find difficult to give up. And yet he was constantly reminded of the gulf that separated them. She was from a lower class. The curvaceous body and shameless sensuality he so loved in private was embarrassing when they were in public. Indiana ate with relish, sopped up sauce with her bread, licked her fingers, and always ordered second helpings of dessert, to Alan’s astonishment—he was used to the women of his own class who thought anorexia was a virtue and death was preferable to the terrible shame of a few extra pounds. You could tell a woman was rich if you could see her bones. Though Indiana was far from overweight, Alan knew his friends would not appreciate that unsettling beauty she had, like a Flemish milkmaid’s, nor the bluntness that sometimes bordered on vulgarity, so he avoided taking her to places where they might run into anyone he knew. On those rare occasions when this was likely—at a concert or at the theater—he would buy her a suitable dress and ask her to pin her hair up. Indiana always acquiesced with the playfulness of a child dressing up, but over time these tasteful little black dresses began to constrict her body and sap her soul.

Alan’s most thoughtful present had been the weekly flowers—an elegant ikebana arrangement from a florist in Japantown—delivered punctually to her treatment room at the Holistic Clinic every Monday by a young man with hayfever who wore gloves and a surgical mask. Another extraordinary gift had been a gold pendant—an apple encrusted with diamonds—to replace the studded collar she usually wore. Every Monday, Indiana waited impatiently for her ikebana; she loved the minimal arrangements—a gnarled twig, two leaves, a solitary flower. The diamond-encrusted apple, however, she had worn only once or twice to please Alan before storing it in the velvet case in her dressing-table drawer, since in the voluminous topography of her cleavage it looked like a stray insect. Besides, she had once seen a documentary about blood diamonds and the horrifying conditions in African mines. In the early days, Alan had tried to change her wardrobe, to teach her to be more respectable, instruct her in etiquette, but Indiana had obstinately refused. Given how much work it would take for her to become the woman he wanted, she argued, he would be better off looking for a woman more to his taste.

With his urbane sophistication and his aristocratic English looks, Alan was something of a catch. His female friends considered him the most eligible bachelor in San Francisco because, aside from his charm, he was rumored to be extremely wealthy. The precise extent of his fortune was a mystery, but he lived well, though not to excess: he rarely spent extravagantly and wore the same shabby suits year in, year out; not for him the quirks of fashion or the designer labels worn by the nouveau riche. Money bored him precisely because he had always had it. Thanks to his family name, maintaining his social standing required no effort on his part, and he had no need to worry about the future. Alan lacked the entrepreneurial acumen of his grandfather, who had made the family’s fortune during Prohibition; the pliable morality of his father, who had added to it through shady dealings in Asia; and the visionary greed of his siblings, who maintained it by speculating on the stock market.