Ripper

Here in his suite at the Fairmont, amid the honey-colored silk curtains, the antique, intricately carved furniture, the crystal lampshades, and the elegant French lithographs, Alan shuddered as he thought back to that unpleasant episode with Danny D’Angelo, which had further reinforced his belief that he and Indiana could never live together. He had no patience with promiscuous people like Danny, with ugliness and poverty, nor with Indiana’s indiscriminate generosity, which at first had seemed like a virtue, but over time came to be an irritation. That night, as Indiana wallowed in the jacuzzi, Alan sat in an armchair, still dressed, holding a glass of chilled white wine—a sauvignon blanc produced in his own vineyard solely for his pleasure, and that of a few friends, and three exclusive San Francisco restaurants—while he waited for room service to arrive.

From where he sat, he could see Indiana’s naked body in the water, her unruly shock of curly blond hair pinned on top of her head with a pencil, stray wisps framing her face. Her skin was flushed, her cheeks red, and her eyes sparkled with the pleasure of a little girl on a merry-go-round. Whenever they met at the hotel, the first thing she always did was turn on the hot tub, which seemed to her the height of decadence and luxury. Alan never joined her—the hot water would only raise his blood pressure, and his doctor had warned him to be careful—preferring to watch her from his armchair as she recounted some story involving Danny D’Angelo and some woman called Carol, a cancer victim who had joined the ranks of Indiana’s weird friends. He could not really hear her over the swirling water. Not that he was particularly interested in the story; he simply wanted to gaze at her body reflected in the large beveled mirror behind the bathtub, waiting for the moment the oysters and smoked salmon would arrive, when he would uncork a second bottle of sauvignon and she would emerge from the water like Venus born out of the sea; then he would swathe her in a towel, wrap his arms around her, nuzzle her warm, wet, youthful skin. And so it would begin, the slow, familiar dance of foreplay. This was what he loved most in life: anticipated pleasure.

Saturday, 7

The Ripper players, including Kabel—a humble henchman with no role in the game beyond carrying out his mistress’s orders—had agreed to meet up on Skype. At the appointed time, they were all sitting in front of their computers, with the games master holding the dice and the cards. For Amanda and Kabel in San Francisco, and for Sherlock Holmes in Reno, it was 8:00 p.m.; for Sir Edmond Paddington in New Jersey and Abatha in Montreal, it was 11:00 p.m.; and for Esmeralda, who lived in the future, in New Zealand, it was already 3:00 p.m. the next day. When the game first started, they had played in a private text-based chat room, but when—at Amanda’s suggestion—they started to investigate real crimes, they decided to use video chat. They were so used to dealing with each other in character that every time they logged on there would be an astonished pause when they saw each other in person. It was difficult to see this boy confined to a wheelchair as the tempestuous gypsy Esmeralda, to imagine the black kid in the baseball cap as Conan Doyle’s celebrated detective, or this scrawny, acne-ridden, agoraphobic teenager as a retired English colonel. Only the anorexic girl in Montreal looked a little like her character—Abatha, the psychic, a skeletal figure more spirit than substance. They said hello to the games master and aired their concern that they had made little progress in the Ed Staton case during the previous session.

“Let’s discuss what’s come up in the Case of the Misplaced Baseball Bat before moving on to the Constantes,” suggested Amanda. “According to my dad, Ed Staton made no attempt to defend himself. There were no signs of a struggle, no bruises or contusions on the body.”

“Which could mean he knew his killer,” said Sherlock Holmes.

“But it doesn’t explain why Staton was kneeling or sitting when he was shot in the head,” said the games master.

“How do we know that he was?” asked Esmeralda.

“From the bullet’s angle of entry. The shot was fired at close range—about fifteen inches—and the bullet lodged inside the skull; there was no exit wound. The weapon was a small semiautomatic pistol.”

“That’s a pretty common handgun,” interrupted Colonel Paddington, “small, easy to conceal in a pocket or a handbag; it’s not a serious weapon. A hardened criminal would use something more lethal than that.”

“Maybe, but it was lethal enough to kill Staton. Afterward the murderer pitched him over the vaulting horse and . . . well, we all know what he did with the baseball bat. . . .”

“It can’t have been easy to get his pants down and position him over the vaulting horse; Staton was tall, and he was heavy. Why do it?”

“A message,” murmured Abatha. “A sign, a warning.”

“Statistically, a baseball bat is often used in cases of domestic violence,” said Colonel Paddington in his affected British accent.

“And why would the killer bring a bat rather than just using one he found at the school?”

“Maybe he didn’t know there would be bats in the gym and brought one along,” suggested Abatha.

“Which would indicate that the killer has some connection to Arkansas,” said Sherlock. “Either that, or the bat has a particular significance.”

“Permission to speak?” said Kabel.

“Go ahead.”

“The weapon was an ordinary thirty-two-inch aluminum bat, the kind used by high school kids—light, powerful, durable.”

“Hmm . . . the mystery of the baseball bat,” mused Abatha. “I suspect the killer chose it for sentimental reasons.”

“Ha! So you’re saying our killer’s a romantic?” mocked Sir Edmond Paddington.

“No one practices sodomy for sentimental reasons,” said Sherlock, the only one who did not resort to euphemisms.

“How would you know?” asked Esmeralda.

“Surely it depends on the sentiment?” said Abatha.

They spent fifteen minutes debating the various possibilities until the games master, deciding they had spent long enough on Ed Staton, moved on to what they called the Case of Branding by Blowtorch, committed on November 10. Amanda asked her henchman to outline the facts. Kabel read from his notes, embellishing the tale with a few choice details like any aspiring writer would.

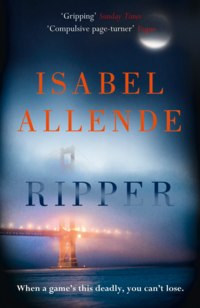

Starting from this scenario, they began to play. Ripper, the kids agreed, had evolved into something much more gripping than the original game, and the players no longer wanted to be limited by the dice and the cards that had previously dictated their moves. It was therefore decided that players could only use logic to solve cases, with the exception of Abatha, who was allowed to use her psychic powers. Three players were tasked with working up a detailed analysis of the murders; Abatha would appeal to the spirit world, and Kabel would continue his offline investigation, while Amanda would coordinate their efforts and plan a course of action.

Unlike his granddaughter, who had no time for the man, Blake Jackson liked Alan Keller and hoped that his affair with Indiana might end in marriage. His daughter needed some stability in her life, a levelheaded man to protect and care for her, he thought. She needed a second father, since he was not going to be around forever. Alan was only nine years younger than Blake, and he clearly had a number of irritating quirks that, as with anyone, would probably only get worse with age. But compared with the men in Indiana’s past he was Prince Charming. He was the only one Blake could really talk to about books, or about culture in general. Indiana’s previous boyfriends—beginning with Bob Martín—had all been jocks: strong as a bull and about as smart. His daughter did not usually appeal to intellectuals, so Alan’s arrival had been a godsend.

As a little girl, Amanda had pestered Blake with questions about her parents; she was much too intelligent to believe the fairy-tale version told to her by her grandmother Encarnación. Amanda had been only three years old when Indiana and Bob split up, and could not remember a time when they had all lived under the same roof. In fact—despite Doña Encarnación’s eloquence—Amanda found it difficult to imagine her parents together at all.

The fifteen years since her son’s divorce had been agony for Encarnación, a devout Catholic who said the rosary every day and regularly prayed to Saint Jude—the patron saint of hopeless causes—lighting votive candles in the hope the couple would be reconciled.

Blake loved Bob Martín like the son he’d never had. He could not help himself: he found himself moved by his former son-in-law’s spontaneous displays of affection, his utter devotion to Amanda, his loyal friendship for Indiana. But he did not want Saint Jude to miraculously bring them back together. The only thing they had in common was their daughter. Apart, they behaved like brother and sister; together, they would inevitably have come to blows.

They had met in high school when Indiana was fifteen, and Bob twenty. Officially, he should have already graduated, and any other school would have thrown him out when he turned eighteen, but Bob was the captain of the football team and the coach’s blue-eyed boy; to the other teachers he was a nightmare they tolerated only because he was the finest athlete to play for the school since its founding in 1956. Good-looking and arrogant, Bob aroused violent passions in the girls, who plagued him with propositions and threats of suicide, while inspiring a mixture of fear and admiration in the boys, who bragged about his sporting prowess and his daring pranks but kept a wary distance, since, if his mood changed, Bob could knock them down with his little finger. Indiana, who had the face of an angel, the body of a grown woman, and a tendency to wear her heart on her sleeve, rivaled the football captain in popularity. She was a picture of innocence, while he had a reputation as the devil incarnate: no one was surprised when they fell in love, but anyone who hoped she would be a good influence on him was sorely disappointed. The opposite happened: Bob went right on being the bonehead he had always been, while Indiana plunged headfirst into love, alcohol, and pot.

Soon afterward, Blake noticed that his daughter’s clothes suddenly seemed too tight, and she was often in tears. He questioned her relentlessly until finally she confessed that she hadn’t had her period in three or four months, maybe five—she wasn’t sure, since she’d always been irregular. Blake buried his face in his hands. His only excuse for missing the obvious signs that Indiana was pregnant, just as he had turned a blind eye when she stumbled home drunk or floating in a marijuana haze, was the fact that his wife, Marianne, was seriously ill, and he spent all his time taking care of her. He grabbed his daughter by the arm and took her first to a gynecologist, who confirmed that the pregnancy was too far advanced to consider a termination; next, to the school principal; and finally to confront the lothario responsible for her condition.

The Martín house in the Mission district came as a surprise to Blake, who was expecting something more modest. Indiana had told him only that Bob’s mother had a business making tortillas, so Blake had naturally expected to find an immigrant family in straitened circumstances. When Bob heard that Indiana and her father were coming to visit, he disappeared, leaving his mother to defend him. Blake found himself face-to-face with a beautiful middle-aged woman dressed all in black save for her fingernails and her lips, which were painted flame red. She introduced herself as Encarnación, widow of the late Señor Martín. The house was warm and welcoming, with heavy furniture, threadbare carpets, toys strewn over the floor, family photographs, a cabinet filled with football trophies, and two plump cats lounging on the green plush sofa. Enthroned on a high-backed chair with carved lion’s-paw feet, Bob’s grandmother sat ramrod straight, dressed in black like her daughter, her gray hair pulled back into a bun so tight that from the front she looked almost bald. The old woman looked Blake and Indiana up and down without a word.

“I am devastated by my son’s actions, Señor Jackson,” the widow began. “I have failed as a mother, failed to instill in Bob a sense of responsibility. What good are all these shiny trophies if the boy has no sense of decency?” she wondered rhetorically, gesturing to the cabinet.

Blake accepted the small cup of strong coffee brought by a maid from the kitchen and sat down on the sofa, which was covered in cat hair. Indiana remained standing, her cheeks flushed with embarrassment, her hands clasped over her blouse to hide her bump, while Doña Encarnación proceeded to give them a potted family history.

“My mother here—God preserve her—was a schoolteacher in Mexico, and my father—God forgive him—was a bandido who abandoned her just after they got married to seek his fortune here in America. At first she got one or two letters, but then months went by with no news. Meanwhile, I was born—Encarnación, at your service—and my mother sold what little she had and, with me in her arms, set off to find my father. She traveled all over California, and we stayed with Mexican families who took pity on us. Finally we arrived in San Francisco, and my mother found out that her husband was in jail for killing a man in a brawl. She visited him only once, told him to take care, then rolled up her sleeves and got to work. In America, she had no future as a schoolteacher, but she knew how to cook.”

Since her daughter spoke of her as though she were dead, or a character in some myth, Blake took it for granted that the grandmother seated on her ceremonial throne spoke no English. Doña Encarnación went on to explain that she had grown up tied to her mother’s apron strings and working from a very early age. Fifteen years later, when her father was released from prison, wizened, sickly, and covered in tattoos, he was duly deported. His wife did not go back with him to Mexico; by then her love for him had withered, and besides, she had a successful business selling tacos in the heart of the Mission district. Not long afterward, young Encarnación met José Manuel Martín, a second-generation Mexican who had a voice like a nightingale, a mariachi band, and American citizenship. They were married, and he joined his mother-in-law’s thriving business. By the time of Señor Martín’s untimely death, the Martíns had succeeded in amassing five children, three restaurants, and a tortilla factory.

“When it came, death found José Manuel—may God enfold him in his holy breast—singing rancheras,” said the widow. Her two daughters, she added, now ran the Martín family business, while her two eldest sons had respectable jobs in their professions; all of them were devout Christians and devoted to their family. The only child who had ever caused her heartache was her youngest son, Bob, who had been only two years old when she was widowed and had therefore grown up without a father’s firm hand.

“I’m sorry, Señora.” Blake sighed. “To tell the truth, I’m not sure why we came. There is nothing anyone can do. My daughter’s pregnancy is already too far advanced.”

“What do you mean, nothing anyone can do, Señor Jackson? Bob must accept his responsibilities. In this family, a man does not go around fathering bastards. Pardon my language, but there is no other word, and I feel it best to be absolutely clear. Bob will have to marry the girl.”

“Marry her?” Blake leaped to his feet. “But Indiana is barely fifteen!”

“I’ll be sixteen in March,” his daughter corrected him in a whisper.

“You shut your mouth!” roared her father, though he had never before raised his voice to her.

“My sainted mother has six great-grandchildren—my grandchildren,” said the widow. “Together we have helped to raise them, just as we will help to raise this child when it comes along, by the grace of God.”

In the silence that followed this pronouncement, the great-grandmother rose from her throne, walked over to Indiana, studied her coldly, and said in perfect English:

“What is your name, child?”

“Indi—Indiana Jackson.”

“I don’t much care for the name. Is there a Saint Indiana?”

“I’m not sure. My mom called me that because that’s where she was born.”

“Ah!” murmured the old lady, speechless. She stepped closer and stroked the girl’s swollen belly. “The baby you are carrying is a girl. Make sure you give her a good Catholic name.”

The following day, Bob Martín appeared at the Jackson house on Potrero Hill wearing a dark suit and a funereal tie, carrying a bunch of moribund flowers. He was flanked by his mother and by one of his brothers, who gripped the boy’s arm like a prison warden. Indiana did not come downstairs—she had spent the whole night crying, and was in a terrible state. By now Blake was resigned to the idea of marriage, having failed to persuade his daughter that there were less permanent solutions. He had tried all the usual arguments, though he stopped short of threatening to have Bob charged with statutory rape. The couple was quietly married at City Hall, having promised Doña Encarnación that they would have a church wedding as soon as Indiana—who had been raised by agnostics—could be baptized.

Four months later, on May 30, 1994, Indiana gave birth to a little girl, just as Bob’s grandmother had predicted. After hours of excruciating labor, the child emerged from her mother’s belly and was dropped into the hands of Blake Jackson, who cut the umbilical cord using scissors given him by the duty doctor. Blake quickly took his granddaughter, swaddled in a pink blanket, a woolly cap pulled down over her eyebrows, to introduce her to the Martín family and to Indiana’s school friends, who had flocked to the hospital, bringing balloons and cuddly toys. When she saw her only granddaughter, Doña Encarnación sobbed as though she were at a funeral—her other grandchildren counted for little, since all were boys. She had spent months preparing, had bought a traditional bassinet with a starched white canopy, two suitcases full of pretty dresses, and a pair of pearl earrings that she planned to put in the little girl’s ears as soon as her mother’s back was turned. Bob’s brothers spent hours searching for him, trying to make sure he was present for the birth of his daughter, but it being Sunday, the new father was off celebrating another win with his football team and did not show up until the early hours.

As soon as Indiana could hobble out of the delivery room and sit in a wheelchair, her father took her and her newborn upstairs to the fourth floor, where Marianne, the child’s other grandmother, lay dying.

“What are you going to call her?” asked Marianne, her voice scarcely audible.

“Amanda. It means bright, clever, deserving to be loved.”

“That’s pretty. In what language?”

“Sanskrit,” explained her daughter, who had dreamed of India ever since she was a little girl, “or it could be Latin. But the Martíns think it’s a Catholic name.”

Marianne only just lived long enough to see her granddaughter. With her dying breath, she offered Indiana one last piece of advice. “You’re going to need a lot of support to raise your daughter, Indi. You can rely on your papa and on the Martín family, but don’t let Bob wash his hands of her. Amanda will need a father, and though he’s a little immature, Bob is a good boy.” She was right.

Sunday, 8

Thank God for the Internet, thought Amanda as she got ready, because if I’d had to ask the girls at school, I’d look like a complete idiot. Amanda had heard about raves, those secret hedonistic gatherings of teenagers, but could not picture what they were actually like until she looked up the term online and discovered everything she needed to know, including the appropriate dress code. She hunted down what she needed from her wardrobe, ripped the sleeves from an old T-shirt, shortened a skirt with irregular scissor slashes, and bought a tube of luminous paint. The idea of asking her father whether she could go to a rave was so absurd that it did not even occur to her. He would never have agreed; in fact, had he known, he would have shown up with a whole battalion of officers and ruined the party. She told him she didn’t need a ride, that a friend would drop her back at school, and he didn’t seem to notice that she looked more like she was heading to a carnival than back to boarding school—this was how his daughter usually dressed.

Amanda caught a cab that dropped her at Union Square at 6:00 p.m., prepared to wait for some time. By now she should already have been back at school, but she had taken the precaution of letting the teachers know she would not get back until Monday morning so no one would call her parents. She had left her violin in the dorm, but there was nothing she could do to get rid of her heavy backpack. She spent fifteen minutes watching the square’s newest attraction: a young man smeared from head to foot in gold paint who stood frozen like a statue while tourists posed to have their picture taken. She strolled around Macy’s and, in one of the restrooms, painted luminous stripes on her arms. Outside, it was dark now. To kill time, she went to a hole-in-the-wall that served Chinese food, and at nine arrived back at Union Square, by now empty but for a few dawdling tourists and the beggars who came from colder climates to winter in California, settling in their sleeping bags for the night.

She sat underneath a streetlamp, playing chess on her cell phone, wrapped in one of her grandfather’s old cardigans, something that always soothed her. She checked the time every five minutes, anxiously wondering whether Cynthia and her friends would pick her up as promised. Cynthia was a girl from school who had bullied her for three years and then suddenly, without explanation, invited her to this rave, even offering her a ride to Tiburon, forty minutes’ drive from San Francisco. Somewhat skeptical, since this was the first time they had included her, Amanda nevertheless immediately accepted.

If only Bradley, her childhood friend and future husband, were here, she would feel more confident. She had spoken to him a couple of times earlier in the day, though she said nothing about her plans for the evening, afraid that he might try to dissuade her from going. With Bradley, as with her father, it was best to recount the facts after the disaster had occurred. She missed the boy that Bradley had once been, someone warmer and funnier than the straitlaced young man he had become almost as soon as he started to shave. As children they had played at being married and found other convoluted ways to satisfy their childish curiosity, but barely had Bradley reached his teens—a couple of years before she did—than their beautiful friendship began to flounder. In high school Bradley was a high flyer: he was captain of the swim team, and when he discovered he could attract girls whose anatomy was more exciting, he began to treat Amanda like a little sister. But Amanda had a good memory, and had not forgotten the secret games they played at the bottom of the garden, something she planned to remind Bradley about when she went to MIT in September. In the meantime, she did her best not to worry him with minor details like this rave.

Her mom’s fridge usually contained a few “magic brownies,” gifts from Matheus Pereira, which Indiana would leave there for months until they were covered with green mold and fit only for the garbage. Amanda had tried them just to be in tune with the rest of her generation, but she could not see what was so entertaining about wandering around out of her head. To her it was time wasted that might be better spent playing Ripper. But that Sunday evening, wrapped in her grandfather’s threadbare cardigan, sitting beneath the streetlamp on Union Square, she thought nostalgically about Pereira’s “space cakes”; they would have calmed her down.

By half past ten Amanda was on the point of crying, convinced that Cynthia had made a fool of her out of sheer spite. When word got around about her humiliation, she would be the laughingstock of the school. I will not cry, I will not cry, she said to herself. Just as she picked up her cell phone to call her grandfather and ask him to come and get her, a van pulled up on the corner of Geary and Powell and someone leaned halfway out the window, waving frantically to her.