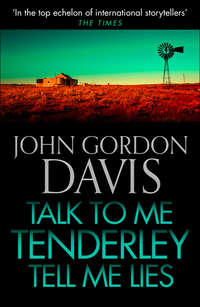

Talk to Me Tenderly, Tell Me Lies

He opened his saddle-bags, took out his camping stove, a packet of rice, a can of bully beef, a little pot, and carried them all into the cottage kitchen. He put water and rice in the pot, cranked up the stove, put the pot on top, and sat down to wait.

Man, he was tired from the digging; he’d thought his shoulders and arms were tough after holding down that motorbike for three years, but that pickaxe in Aussie terra very firma was something else.

God, he felt sorry for her about the dog … He closed his eyes. But instead of Oscar, he saw again those long, plump, bare legs beside him on the kitchen table, her dimpled bottom barely covered by her knickers.

He ate a bellyful of rice and bully beef, then collapsed on the bed.

He lay there, thinking of the way she had felt in his arms. Had she been annoyed? No, he was almost sure not. In fact he was almost sure that for an instant she had almost responded – then she had backed off, as if she’d been surprised at herself.

He stared at the ceiling, trying to remember and interpret every moment; then he smirked mirthlessly: it was just his wishful thinking, imagining she had wanted to respond. That was Ben Sunninghill hoping his luck had changed, stumbling across a lonely woman in the middle of the Australian Outback. No, she hadn’t wanted to respond, she was just taken by surprise …

He sighed, closed his eyes and resolved to put it out of his mind. Too bad. And he wasn’t going to have a chance to find out for sure, leaving this afternoon; he’d never get another natural opportunity of taking her in his arms.

Too, too bad …

Ben awoke an hour later feeling refreshed, though his shoulders were stiff. It was half past three. The ringing silence of the Outback. He creaked off the bed, went out on to the porch and listened.

Not a sound of life. Helen had been resting for almost three hours. He hoped she was sleeping, not lying there red-eyed.

He washed his dishes, packed his saddle-bags and straightened up the bedroom. He found a broom and gave the place a quick sweep, and scoured the sink and the bathroom. Then he put on his black leather breeches and boots.

It was after four o’clock when he was ready to leave. He took his box of jeweller’s tools from his saddle-bag and started walking to the main house to see if Helen was up: he didn’t take the motorbike in case she was still asleep.

The kitchen was empty. Silence. He went quietly to the inner door and carefully opened it.

Helen gasped and jumped backwards. She had been about to open the door from the other side. She was wearing only her panties, and Ben glimpsed two large breasts before her hands shot up to cover them. He slammed the door. ‘I’m terribly sorry,’ he called. ‘I was coming to find out if there was any sign of life.’

Helen was dashing back down the passage to her bedroom. ‘I was just coming to put the kettle on!’

‘Shall I do it?’ he called.

‘Yes.’

He went to the sink and filled the kettle. God, he hoped she hadn’t misinterpreted that incident, thinking he was tiptoeing through the house to get between the sheets with her! Your actual Ben Sunninghill may have been fool enough to think earlier that his luck might have changed, but he wouldn’t be so crass as to try that – God … He turned and walked out into the yard, as if to disassociate himself from her nakedness until the kettle boiled.

Five minutes later she came into the kitchen, dressed in jeans and a shirt. She had put on some lipstick and run a comb through her hair, but wisps hung untidily.

‘I’m very sorry,’ Ben said sincerely.

‘That’s okay,’ she said briskly. ‘Nothing you haven’t seen before.’ Her face was strained.

‘A handsome brute like me,’ he agreed, then regretted the words at once, and added hastily: ‘Did you get some sleep?’

‘No,’ she sighed tensely. ‘I couldn’t stop thinking about Oscar. But I’m all right. Tea or coffee?’

‘Coffee, please. Well,’ he went on brightly, to put her mind at rest, if that’s what it needed, ‘I’m all packed and ready to leave. Just give me your ring and I’ll put the diamond in.’

‘Oh … Thank you.’ She slid the ring off her finger and took the diamond from her pocket.

Ben sat down at the table, opened his toolbox, and selected a small pair of pliers. He picked up the diamond and carefully slotted it into its bed.

‘Or would you prefer a beer?’ Helen said.

‘Coffee’s fine.’

‘Well, dammit, I’m going to have a beer!’ She went to the pantry, opened the refrigerator and came back with two cans. ‘Four-X.’ She ripped open a can and passed it to him, then sat down.

‘Thanks.’ He lifted the beer and took four long swallows. As he began to clamp the diamond into its bed, he asked: ‘Can you get another dog easily? A puppy?’

‘Oh,’ she said, ‘I don’t want another one. Not yet. Jack Goodwin – he owns the hotel in Burraville – his Boxer bitch has a litter of puppies, but I couldn’t face taking one yet. It wouldn’t seem … right.’

‘Tempus luctus?’ he murmured as he worked. ‘Well, I think—’

She demanded: ‘How do you know Roman law?’

He was equally surprised. ‘How do you know tempus luctus is a Roman law maxim?’

‘I did two years of it at Uni. Tempus luctus was a period of mourning, during which a widow was not allowed to remarry.’

Ben grinned. ‘Yes, but I think it had something to do with paternity, didn’t it – being able to establish who was the father of any child born within a certain time of the first husband’s death?’ He smiled. ‘So it doesn’t apply to your case. I think you should get another puppy as soon as possible.’ He gave the ring a final tweak, and handed it to her. ‘Here, that won’t fall out again.’

‘Oh, thank you …’ She slipped it back on her finger. She admired it. ‘Great. You’re really being a great help around the McKenzie household.’ She admired the ring again. ‘So, how does a gemologist know so much Roman law?’

Ben took a swig of beer. ‘I don’t. I just bought a book on it once. Bedside reading.’

‘Good God – Justinian’s Twelve Tables for bedside reading?’

He smiled. ‘Did you get a degree in law?’

‘No.’ She sighed. ‘I didn’t get a damn degree in anything. Got married instead, in my third year.’

‘Pregnant?’

She gave him an amused look that was not a smile. ‘You’re rather blunt, aren’t you? No, I can’t blame my stupidity on the slings and arrows of outrageous Mother Nature. I was simply in love.’

‘Was?’ Immediately he wished he hadn’t said that.

Her reply was a touch pointed: ‘I still am.’

Ben took another swig of beer. ‘Then it wasn’t stupid.’

She looked at him, then sighed. ‘Oh, of course it was. I should have finished my degree first. I could have had that achievement to … to my name. To be proud of.’

Ben said: ‘Aren’t you proud now? You’ve raised a good family.’ He waved a hand. ‘You run this station.’ He added: ‘You’re a fine woman. A good woman.’

She shot him a look. ‘Thanks. Oh, of course I’m proud of my family. And of Clyde. I simply mean I could have had both. All that, and a degree, if I’d been patient. And maybe … travelled a bit.’

‘Enriched your life first?’

She lifted the can to her mouth and swallowed. Then sighed.

‘Exactly. I intended to see the world after I got my degree. Like you’re doing. I don’t mean on a Harley-Davidson, but what kids did in those days – hitch-hike around Europe, knock around on student railpasses. Maybe buy a camper. Work in London a few months.’ She sighed again. ‘It broke my parents’ hearts.’

‘That you didn’t travel?’

‘No, they’re old-fashioned about travel – Australia has everything, why waste money on travel? No, that I didn’t finish my degree. They thought I was going to be the one to break out of the farming mould and have a sophisticated life as a schoolteacher or doctor’s wife in Sydney or’ – she waved a hand – ‘even the glittering lights of Bundaburg itself.’ She snorted softly. ‘They’re sheep farmers near there. That’s how I met Clyde. Anyway, they had to save hard to put me through Uni, and I threw it all away.’ She added, in self-defence: ‘Though I did help by working at night as a waitress and so forth.’

‘Which university?’

‘Brisbane.’

‘Did you enjoy it?’ He upended the beer can and emptied it.

She sighed. ‘Beaut. Have another one?’ She got up before he answered and fetched two more cans. ‘Left over from Clyde’s last visit. Or would you prefer brandy?’

‘No, it’s good beer. Why do they call it Four-X?’

‘Because Queenslanders can’t spell beer.’

He threw back his head and laughed.

She smiled: ‘Old joke.’

‘Good joke.’ He took a grinning swallow. ‘So? Your parents didn’t approve of Clyde?’

She took a big sip and shook her head.

‘No, they thought Clyde was beaut. Even though he’s a Catholic. He was a sheep-shearer. You know, in this country sheep-shearers are highly skilled itinerant workers. And well paid. And he’s a very solid bloke, Clyde. Nice-looking, good manners, hard-working. He’d also worked on the mines and been a shift-boss at only twenty-six. That mightn’t sound like much, but believe me, underground is very responsible work. Anyway, he was buying this station on a mortgage, that’s the only reason he was sheep-shearing, to make extra seasonal money.’ She sat back. ‘No, my parents had nothing against Clyde – my mother even flirted with him! Not seriously, of course, she just thought what a nice man, and Dad thought he was a great guy. But in their view I was destined for greater things than the Outback. They begged me to at least finish my degree first.’ She sighed again. ‘But, we were madly in love. And he was about to disappear into the Outback again and he was afraid that in another year I’d meet somebody else. “All those smart guys at Uni,” he said. And I was scared he’d meet some other lusty wench. Et cetera, et cetera.’

Ben smiled. ‘How old is he?’

‘Seven years older than me. Forty-nine.’

‘So you got married and came straight to this station?’

‘Yes. Dad shouted us a week’s honeymoon on Lord Howe Island first as a wedding present. That’s beautiful. Wonderful reefs …’ She grinned mirthlessly: ‘The furthest overseas I’ve ever been.’

‘That was nice of him.’

‘Very. Oh, my parents are lovely people. Dear, dear people.’

‘Do you get to see them much?’

She twirled her beer can. ‘Only very occasionally. Two years ago was the last time. They’re over a thousand miles away, and you know what the roads are like out here.’ She got up. ‘I’m going to have a brandy. And you?’

He looked at his watch. ‘Not if I’m riding. I’ll have another beer in a minute, if you’ve got one.’

She hesitated a moment; then she said: ‘Must you leave today? It’ll be sunset soon.’

Ben was taken by surprise. He was delighted to stay another night. And, who knows …? But he put on a show of indecision.

‘No, I shouldn’t. I don’t want to impose—’

‘You’re not imposing. The cottage is empty. And I’m enjoying talking. It’s a nice change for me to have company.’

He smiled: ‘Instead of talking to …’ – he was about to say ‘Oscar’, then managed to change it – ‘the wall?’

She smiled bleakly. ‘Oscar, you mean. Oh …’ She slumped her shoulders. ‘Oh, I’d give my front teeth to have that doggie back. However …’ She forced a bright smile. ‘So you’ll stay another night?’ She added hastily: ‘In the cottage.’

‘Of course. I mean of course I’ll sleep in the cottage. If that’s okay, I’d love to – thank you.’

‘Thank you, for all your help. Good … So, you’ll have a brandy?’

‘Sure,’ he grinned. ‘What the hell!’

‘What the hell!’ she agreed. She disappeared back into the pantry and returned with the bottle and two glasses. ‘Water?’

‘Straight. What the hell.’

‘What the hell. Aussies make good brandy.’ She sat and sloshed the liquor into the glasses. He noticed she suddenly appeared a little tipsy, as if she had dropped her guard.

‘And good wine,’ he said.

‘And wine.’

‘I’ve got a couple of bottles of Shiraz in my saddle-bags I can fetch.’

‘Keep it for the road. Where’re you heading tomorrow?’

He took a sip. ‘East. Brisbane. Then Townsville, Cairns, then across to Darwin. I’ll have to look at the map.’

‘Oh, Brisbane …’ She sat back with a sad smile. ‘Those were happy days.’ She sighed nostalgically, and took a big sip of brandy.

He did the same. He was glad she was relaxing after the trauma of burying her dog – and optimistic about the evening ahead? ‘So,’ he said, ‘you regret …’ He changed it. ‘I mean, but surely you don’t regret getting married?’

She snorted softly. ‘No,’ she said, ‘how can you regret all that? Your husband? Your children?’ She waved a hand vaguely. ‘Even this lonely life. This is my home. It would be … unnatural to regret that. Like Lady Macbeth saying “Unsex me here”.’ She shook her head. ‘No, of course I don’t regret any of those actual things – I just wish I had got my degree, done my travelling … enriched my life first.’ She shrugged. ‘For just a couple of years, then done what I did. With Clyde.’

She looked at Ben, as if about to continue, but didn’t.

‘But?’ he said.

She hesitated. ‘But nothing.’

‘You were about to say “but”.’ He smiled that smile.

‘Was I?’ She smiled back at him, self-consciously. ‘Yes, I was.’ She breathed deeply. ‘What I mean is this: But the kids have all left the nest now. One by one they had to go off to boarding-school in Rockhampton, when the School of the Air wasn’t enough for them anymore.’

‘“School of the Year”?’

‘Air. The radio. The government broadcasts lessons for Outback kids. At regimented hours the kids sit at their desks and tune into the government’s education programmes, just as if they were at school. Very good it is, too. And my kids were very conscientious. I made them conscientious. And I helped them, and the older ones helped the younger ones, et cetera, and it’s all pretty effective. But,’ she shrugged, ‘you reach a point where that’s not enough. They need the society and competition of other kids – and sport, and the esprit de corps of normal schooling. So …’ She sighed. ‘One by one, off to boarding-school they had to go. Until even little Cathy went, year before last.’

‘How old is she?’

‘Eleven, now.’

‘And the eldest?’

‘Tim. Seventeen.’ She smiled wanly. ‘We kind of had them bang, bang, bang. Went to bed too early, I guess. There was no television out here in those days.’

He grinned. ‘And …?’

‘And what?’

‘You started off by admitting the “But”.’

She smiled. ‘Well, so, the kids are all doing fine at school. Good at games, good at their lessons. They come home once a year, Christmas holidays, for six weeks. The other holidays they go to my parents.’ She shook her head. ‘And when they come home, they’re full of what it’s like in Rockhampton, what fun it all is, and after a couple of weeks they can’t wait to get back there. Their mates and all. And Tim thinks he’s in love with the head girl – he’s head prefect this year – and Wendy’s got a crush on some young giant in the footie team, and there’s no social life for them here, and so on. And Jacqueline’s mad about tennis. Even Cathy complains that there’re no newspapers – she wants to be a fashion reporter, would you believe? Age eleven! And they all want to go and disport themselves on the beaches and ride on those surfboards.’ She raised her eyes in despair. ‘And the bosoms on my girls …? Even little Cathy is busy hatching two beauts.’

Ben smiled, and couldn’t help glancing at mother’s endowments. ‘And …?’

Helen took a sip of brandy. She gave an appreciative shudder.

‘And, well, now Clyde has had to go back to the mines to pay for this little lot. With the droughts, and all. And, in fact, he’s okay, too. He’s got a nice bachelor bungalow, good tucker, good pay – thank God. He’s very generous, sends me enough money and all that – he’s even got a laundry and a cleaning lady. And he deserves it. But the point is …’ She paused, then took a deep breath. ‘The point is, none of them need me anymore.’ She shook her head at him. ‘They’re all okay. Well provided-for. As I am. But the point is, what about me?’ She looked at him. ‘What is my purpose now?’

He ventured: ‘You’re here. They know you’re here to come home to. Mum.’ He smiled. ‘The rock in their lives. And, you’re looking after the station. The cattle.’

She snorted. ‘Oh, the station … Do you know how many cattle we’ve got out there now? Sixty-five only. And a hundred and fifty or so sheep, until the lambing begins. We sold off the rest last year when they still had some meat on them. And even they don’t need me – they’ve got Billy.’

‘When he isn’t drunk or on walkabout.’

‘But that’s one of the reasons he’s so hopeless – there’re so few animals. Nothing. We haven’t even got a drinking-water crisis because there’re three windmills still producing and fifteen acres of lucern under irrigation to feed the animals if the drought continues.’ She shook her head. ‘The station doesn’t need me. The home doesn’t need me. So …?’ She looked at him. ‘Everybody’s okay. But what have I got?’ He started to speak but she continued, in exasperation: ‘Oh, I don’t mean, what have I got. I’ve got a perfectly good home and a loyal husband and enough money to get by. We’re hard-up, but we’re not broke. What I mean is – what is my usefulness now? What am I doing with my precious one-and-only life? With my perfectly good head? With my hopes? With the … remnants of my youthfulness, my energy and … creativity? With my life?’

Ben looked at her sympathetically. It was getting dark. He got up, went to the back door and pressed the green button. There was a distant doem doem doem as the generator started up. The kitchen light loomed on.

‘Thanks,’ she said, without looking up.

He sat down again. ‘What do you want to do with it? Your life.’

She snorted softly, put both elbows on the table and rested her chin in her palms. ‘I don’t know.’

He said: ‘Leave? Go and do the things you wanted to do when you’d finished your degree?’

She pressed her fingertips to her eyelids. ‘Oh, how can I do that?’

‘Easy. Just pack a bag and do it. Even if it’s just for a year or two.’ He added: ‘You could crank up that VW van.’

She lowered her hands. ‘Just take off on a holiday? Clyde would have a fit! Him working so hard to provide for the family and me just taking off, spending the money?’

‘You need only spend the money he sends you anyway for your own maintenance. As you say, the ranch doesn’t need you – why should Clyde be a dog in the manger over your time? Your life? Have you any money saved? Of your own, I mean.’

She made a wry face. ‘A couple of thousand dollars, maybe, in the post office.’

‘You could get a job somewhere.’

‘Doing what? The only thing I’m trained for is damn housework. Though I did do a short course at Uni in shorthand and typing, but I’ve forgotten it all.’

‘You’d pick it up again quickly. You’d be able to get a job in an office somewhere, an intelligent woman like you.’

She looked at him, then sighed.

‘Oh, I’d love to do it. But Clyde would never allow it.’

Ben frowned. ‘You don’t need his permission. As you say, it’s your precious, one-and-only life, to do with what you want. If you want to keep Clyde happy, forget it. But if you want to have a couple of years enriching your life, do it, even without his permission if necessary. But then there would be a price.’

She rested her face in her hands again. ‘And that is?’

‘Depends. You may never be the same again – you mightn’t want to come back. Or Clyde might not want you back. In both cases the price would be called Sadness. Even Grief. And there’s another one, unless you’ve got enough money – it’s called Hardship. And another, called Loneliness. Enriching your life can be the loneliest business in the world.’

She looked at him through her parted fingers.

‘What are you saying to me, Ben?’

He smiled. ‘I’m just being realistic. You said you wanted to do more with the precious remnants of your life. You said you were helpless to do so. I’m just trying to show you that you’re not helpless, but there’s probably a cost. So, you must weigh the cost and decide what’s worth what, and try to be satisfied with your decision.’

She gave a big sigh.

‘Oh how I envy you.’ She sat there, her face in her hands. ‘Oh … I’m drunk.’ She sat up and lowered her hands. ‘Brandy and beer will do it to me every time. I had a couple of brandies before you came in, to try to sleep.’

He shrugged. ‘So, get drunk.’

‘I’m supposed to be the hostess.’

‘So, I’ll get drunk with you.’

She looked at him; her eyes were a little puffy. ‘Why?’

He smiled at her. Why had she said why, like that? Because she suspected he wanted to get her drunk so he could have another grab of her? Perish the thought! That sweet possibility hadn’t entirely escaped him, but even sex-starved Ben Sunninghill wasn’t a cad, was he? His reply was almost truthful:

‘Why not? We’re enjoying ourselves. They’re our lives, they’ll be our hangovers. You’re answerable only to yourself.’

‘What does that mean?’

Oh, dear. Tramsmash Sunninghill. So she really did think he might be after her drunken body. ‘Only what it says. You’ve had a tough day. You want to get drunk, do so. Nobody’s here to criticize you.’ (He wished he hadn’t said that, too.)

She snorted wearily, apparently satisfied.

‘No … I won’t get drunk. Or drunker. I’ll go’n sleep now, if you’ll excuse me.’

‘Of course.’ He was very disappointed that the party was over almost before it had begun. ‘But let me make you something to eat, you haven’t eaten all day.’

‘I’m not hungry. I had a big sandwich this afternoon, with the brandies. I should offer to make you something but I’m suddenly too drunk to try. I’m a piss-poor hostess, aren’t I?’

‘You’re a lovely hostess. And I’ve plenty to eat, in my saddle-bags.’

‘I’m sure you have, Mr Adventurous Sunninghill. You’re self-sufficient. Answerable only to yourself.’ She looked at him, then repeated wearily: ‘Oh, how I envy you.’

He smiled. What to say? She held up a finger. ‘There’s one thing I’d like you to do before you go to bed. Please wait right here until I’m in my bedroom. Then press the red button and shut the generator down.’

‘Sure.’

‘Otherwise,’ she said, ‘what always happens is I’ve got to press the red button myself, then dash through to my bedroom in the dark. Which gives me the willies.’

‘You could have a candle ready,’ he said. ‘Or a flashlight.’

‘Yes, but I never do have a candle ready, do I? And besides, candle-light is spooky when you’re walking alone through a big empty house, isn’t it? I kind of prefer to run, then lock myself in the bedroom.’

He frowned. ‘Do you really lock yourself in your bedroom every night?’ (Oh God, that sounded a terrible question.)

‘Absolutely.’

‘But why?’

She grinned. ‘To keep the spooks out.’

‘Really?’

‘No, not really. I know there’re no such things as spooks. I’ve told all my children that ad nauseam, so it must be true because mummies don’t tell fibs, do they? Mummies,’ she went on, ‘are absolutely pillars of truth and common sense, aren’t they? Mummies are rocks. Veritable lighthouses in stormy seas. Absolute bricks, aren’t they? And mummies know best. Know everything. Mummies aren’t scared of spooks, are they?’

‘Aren’t they?’ Ben grinned.