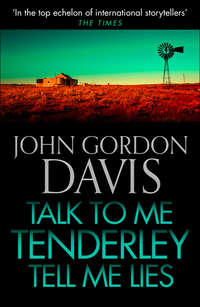

Talk to Me Tenderly, Tell Me Lies

Ben smiled. ‘I’m glad.’

Helen wiped the corners of her eyes. ‘And,’ she said brightly, ‘you’ve got all your hair!’

‘All over,’ Ben agreed.

‘It shows virility!’

‘I tell the girls that, but I’m just told. I’m a fire-hazard.’

She laughed at him: ‘Oh, Ben …’

He smiled, then picked up the new doorlocks and the coil of electrical cable. ‘Well, I’ll fix the locks and extend that generator switch to your bedroom. To outwit the spooks.’

Helen brought her mind to this change of subject.

‘Oh, that’s very kind of you, but Clyde said it’s best where it is.’

Ben said: ‘You’re the one who lives here all alone each night with the spooks, not Clyde. It’s just a simple override switch, so you can shut down the generator from your bedroom when you go to bed. Clyde will still be able to start it and stop it from the kitchen.’

‘Really?’ she said. ‘Why didn’t he know that?’

‘Maybe Clyde’s not a smart-ass like me.’

Ben changed the locks while Helen got her laundry together. Then she fed Dundee while Ben started work on the switch. The puppy wolfed down his food. ‘Like he’s never had meat before!’ she called happily from the yard.

‘Probably hasn’t, living with Jack Goodwin.’

‘Oh, he’s gorgeous!’

‘Jack or Dundee?’

‘Dundee! Oh, Jack’s a real miser. And a terrible gossip. “Radio-Jack”, we call him – tell him anything and it’s all over the Outback by nightfall. Who’s a beautiful boy, then?’

‘Me. Ask my mother.’

‘Oh, you ass!’ She came back into the kitchen, holding a glass of wine. ‘Oh, dear … I’m having a lovely day. Now then – got any laundry you want done? Smart-ass.’ She burst into giggles.

Ben picked his wine glass up from the floor and took a sip. ‘No, thank you, only dirty people need machines to do their laundry. I did mine by hand this morning.’

‘Well, it can’t be very dry. Where is it? In a plastic bag in your saddle-bag?’

‘Right.’

‘Right, and where is it?’

‘Just behind the saddle.’

‘I mean the bike, you fool. Even I can figure out where the saddle-bag is once I find the bike. But I didn’t see it when I came back from Billy’s.’

‘Outside your front door. Black, you can’t miss it, the only black 1000cc Harley-Davidson there.’

‘Oh, you ass!’ She marched to the front of the house. She ferreted through his saddle-bag and found the wet clothes. She took them to the line in the yard, and hung them up. Socks, underpants, vests, shirts. Then she took one shirt down again and returned to the kitchen.

‘Well, this garment needs strong machinery.’ She stuffed it into the washing-machine with her own laundry.

‘Thank you. But you can’t start up the generator to do the washing while I’m working on these wires.’ He added: ‘You could, but you’d have to bury me soon afterwards.’

‘Standing up beside Oscar?’

‘So the grave would have to be a bit deeper, and that ground’s hard. Not that much deeper,’ he admitted reasonably.

She prepared lunch while he led the cable along the kitchen walls and down the passage, tacking it to the skirting board. He bored a small hole in the doorframe and fed the wire through into her bedroom.

It was not very feminine; it seemed a worn, hard-up sort of room. On the far bedside table was a framed photograph of a man, doubtless Clyde: Ben peered across at it, but couldn’t make out much. On the dressing-table near the door was a photograph; four children. Taken recently, Ben thought. The boy, Tim, looked about sixteen: he was a strapping, good-looking lad; short hair, a generous open face, white even teeth – he was going to be what Americans call a ‘hunk’. The three girls were all pretty, with neatly combed blonde shoulder-length hair and generous mouths like their mother; the little one, Cathy, was going to be a beauty. Ben glanced around the room. The double-bed was neatly made. The rugs on the floor were patchy. The wardrobe door was open, he could see dresses hanging, the shelves jumbled with underwear. Below lay a muddle of high-heeled shoes, several mauve pairs among them. So she likes mauve? It would suit her, too her blue jeans suited her, with her blue eyes and blonde hair. One pair looked very sexy, with thin leather straps that she would wind around and tie above her ankles. He felt a desire to tiptoe across and pick them up. He could imagine them on her. Her toenails painted red? Oh dear, dear … The dressing-table was old and chipped. The little jars and bottles of lotions and creams and perfume had a frugal, husbanded air. He felt sure most of them were almost empty, kept for the last smear or drop. Between the dressing-table and the wardrobe was the bathroom. He glanced towards the kitchen, hesitated, then went to the door and looked inside. Untiled walls, an old tub with claw-and-ball feet, the enamel worn away near the plug. An overhead shower with a dull plastic curtain. A toilet. A bidet, obviously recently installed because the cement around its base looked newish. Some towels, a big, damp bathmat, a broken laundry basket. And, on the floor beside the basket, a pair of panties. They lay there with an air of abandonment, as if she had just stepped out of them.

Ben Sunninghill looked at them. They were red, and lacy. And see-through, and brief. He had an almost irresistible desire to tiptoe inside and pick them up. To feel them between his fingers, to hold them to his face …

‘Gotcha!’

He jerked around. Helen was in the bedroom doorway, smiling, Dundee in her arms. ‘Lunch is ready when you are!’

Ben recovered himself, and said easily: ‘I was considering the best place for this override switch. Here by the bathroom door, which is easy for me, or by your bedside? That way is easy for you, but I’ve got to lead the cable right around the room.’

Helen considered the problem tipsily. ‘Bedside makes sense, provided you’ve got enough cable. Then I haven’t got to get out of bed in all my nakedness when I’ve finished reading, hit the switch, dash back, trip over the rug, bark my shins, cuss, scramble up in the dark, feel for the bed, et cetera.’

Ben grinned. ‘Right.’ He added: ‘You’re a funny lady.’

‘Funny ha-ha or funny peculiar?’

‘Both. But delightfully so.’

‘I knew it. Now I’m not only bushwhacked, I’m peculiar!’ She entered the room. ‘Trouble is, if it’s on my side of the bed, that means Clyde’s got to get up – when he’s at home – if he reads later than me, and switch the damn thing off. That’ll irritate him.’

‘Look, who’s this switch for? And how often is Clyde home?’

She pondered a moment. ‘True. To hell with Clyde?’

‘Absolutely.’

‘Okay, on my side of the bed, please.’ Then she happened to glance into the bathroom and see the panties. She went in, scooped them up and stuffed them into the laundry basket. On her way back she closed the wardrobe door. ‘Lunch is ready!’ she repeated. ‘Finish the switch afterwards.’

She had gone to some trouble over lunch. Ben fetched another bottle of wine from his saddle-bag. But he ate very little. ‘I had two meat pies in Burraville just before I left,’ he explained.

‘That’s not very good for you – have some more salad, grown with my own fair hands!’ She was thoroughly enjoying herself.

‘Yes, I saw your vegetable garden. Very impressive.’

‘We’re lucky to have enough water for it – it’s a good well. And we swim in the holding reservoir.’

Ben imagined her in a swimsuit. He suggested: ‘Shall we do that, after we’ve finished work?’

‘Why not?’

Great things can happen in a swimming pool after a long boozy lunch. Ben couldn’t wait. At the very least, the prospect of being semi-naked with her in the common caress of cool water was wildly erotic. He said, for something to say:

‘So Clyde’s a Catholic? And Catholics were bad news in Australia?’

‘Oh, in those days, yes. Australia was very provincial when I was a kid, stuck out on the end of the world, and the majority of us are Protestants. Catholics were regarded as blighted with misinformation. Wops were Catholics – Italian immigrants who ran milk bars. As a girl I felt sorry for Catholics. And marry one? Never! It’s different now, of course.’

‘And Jews? How were they regarded?’

Helen hesitated. ‘Well … Jews have always had a hard time, haven’t they? I guess Australia Fair was no exception.’

‘Go on,’ he smiled: ‘say it. Regarded as furtive. Devious. Clannish. Money-grubbing. And too successful.’ He added, regretfully: ‘Present company excepted.’

She felt uncomfortable with this subject. ‘Well, maybe when I was a girl, but it’s quite different now, of course.’

‘Is it? Jack Goodwin evidently doesn’t think so. And that was before I started bargaining.’

‘Forget Jack Goodwin.’ Then she decided to be bold on this touchy point. ‘But why is it that Jews are so successful?’

He grinned. ‘Because they’re superior.’

‘Seriously.’

‘Seriously. Because we believe we’re the Chosen Race. Says so in black and white in the Bible. We’re different from other people, we’re privileged. So, as the Chosen Race, we have to work hard to justify it, and help each other, to maintain our position. We’ve got an Us-against-Them clannishness. So, we’re rather disliked. And we’re generally physically conspicuous, identifiable as Jews; an obvious target for prejudice.’

‘Well, I’m not anti-Semitic.’

‘No … But do you want your daughter to marry one?’

She was taken aback by the bluntness of the question, even though feeling so jolly.

‘I couldn’t care less, provided he’s a good husband!’ But then she added: ‘Well, I suppose every mother hopes her daughter will marry into her own culture. Religion …’ She faltered, then went on a trifle hastily: ‘But do you believe yours is the Chosen Race?’

He sloshed more wine into their glasses. ‘Yep. Learned it at my mother’s knee. And I’ve only got to look around at all my successful Jewish brethren.’ He grinned. ‘Heard a joke in the Burraville pub this morning. I suspect it was told for my benefit. Anyway, what did the Australian Prime Minister say in his telegram to Golda Meir congratulating her on winning the Six Day War? “Now that you’ve got Sinai, can we please have Surfers’ Paradise back?”’

Helen laughed. She’d heard it, but it was funny again coming from a Jew.

‘No, it wasn’t said for your benefit!’ She took a sip of wine, then asked: ‘Did Jack Goodwin know you were buying the puppy for me?’

‘Yes. Why? He asked me what I wanted a puppy for, on a motorbike. I told him about Oscar.’

Helen puckered one corner of her mouth. ‘Hmm. Did the other blokes in the pub know Dundee was for me?’

Ben shrugged. ‘Sure. Why?’

Helen sighed, but said cheerfully: ‘No, it’s okay. But it’ll be all over the Outback on the bush telegraph.’ She shrugged. ‘So what, I’ll say you’re my cousin from New York!’

‘Your cousin? With this nose?’ Ben sat back. ‘I see. It’s a matter of “What’ll the neighbours think?”’

‘To hell with them!’

‘But would Clyde be annoyed?’

She frowned. ‘No, Clyde knows I would never be … silly.’

Silly? That was a dampener. He wished he hadn’t mentioned Clyde – Clyde wasn’t a subject to bring up when nursing ambitions about that swim with his wife. But all he could do was make light of it. ‘To have an affair with me would be silly?’ Then he added: ‘You’re right, of course. So – to hell with the neighbours; I’ll be gone tomorrow, anyway.’

‘Oh Ben, you shouldn’t talk yourself down so! You’re not so …’ She paused, wishing she hadn’t started the sentence that way.

Ben wished she hadn’t started it that way too. ‘… Totally unattractive?’ He smiled.

She tried to avoid grinning, and tried to speak earnestly: ‘You know what I mean … You’ve a very attractive personality, Ben …’ (Oh Gawd, why’d she put it like that?) She waved a hand and blundered on: ‘You’re charming. Amusing. Witty. And I’m delighted to have your company …’ She trailed off, then ended brightly: ‘And beauty is only skin-deep!’ Oh, God, why had she said that?

Ben smiled wanly. ‘But ugliness goes right to the bone?’ His optimism about that swim was going right out the window. He stood up, embarrassed. ‘Well, I’ll finish rigging that switch—’

‘Oh Ben,’ she cried, ‘you’re not ugly! Finish your wine! Let’s have another bottle …’

He grinned. ‘Sure, bring it to the bedroom and talk to me while I finish that switch.’

CHAPTER 8

She sat cross-legged on the bed with Dundee, sipping wine, aglow with wine, thoroughly enjoying herself. ‘I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to be a lawyer or a teacher. So I took a general arts degree – or started it – majoring in English Literature, but I squeezed in two years of Roman Law, to get credits in case I went on to do an LL.B.’

Ben was crouched at her bedside table, under Clyde’s photograph, rigging the cable along the skirting board. He indicated the picture. ‘Is that Clyde?’

‘Yes.’

‘May I?’ He picked it up. Clyde smiled self-consciously at him, a burly, nice-looking, no-nonsense balding man, uncomfortable in a suit and tie for the occasion. ‘Looks a nice guy.’

‘He is. Very.’

‘Wouldn’t want to get on the wrong side of him, though.’

‘No. But he’s a softie, really.’

Ben replaced the frame on the table and resumed work. ‘I took a degree in English Literature,’ he said.

She blinked. ‘I thought you did whatchacallit – gemology?’

‘I did. But a few years later I decided to do English Lit on the side. University of New York, night classes.’

Helen sighed. ‘Oh, wow. Good on yer. Wish I could do that. Did you think you wanted to teach English?’

Ben tapped a tack into position. ‘No, just for interest. Had a vague idea I’d try writing one day, or try to get into publishing. But, bought a motorbike instead.’

‘But a degree like that’s never wasted! Oh Ben, why do you say you’re not a success? I so envy you your life.’

Ben worked with the wires. ‘Yes, I suppose I’m a success in that I’m doing what most people fail to do, namely savour the world. Or I’m trying to. And I’m learning, the while.’

‘Becoming wise,’ she said with glowing solemnity. ‘That’s what I’d love to do – become wise. … And I’ve got all the time in the world to try to achieve it, by reading. And I do read. But there’s a hell of a lot more to wisdom than book-learning.’

‘Indeed.’

She waved an expansive hand. ‘It’s out there. Beyond the blue horizon. Where you’re going back to. Or forward to. Always forward, that’s the trick!’ She sighed, staring across the room. ‘That’s why I thought I might be a lawyer. The daily human drama of the courtroom, seeing human nature at work. Arguing a case.’ She frowned tipsily. ‘The beauty of words. Of persuasion. Of logic. By the time a lawyer’s my age he must have seen it all.’ She sighed again. ‘I used to spend hours in the gallery of the Brisbane courts.’

‘And why did you consider being a teacher?’

‘Again, the words. The beauty of the English language, and the satisfaction of using it to guide the young.’

He began work on the switch. He said: ‘Have you tried writing? With all this time on your hands?’

‘Have you ever tried?’

He said: ‘No, but I’ll write a book one day. Even if it’s never published, I’ll have done it.’ He smiled. ‘But I wrote a poem once.’ He sat back on his haunches, put one hand on his heart and pointed his screwdriver at the ceiling.

‘The moon shines up there like a cuspidor,

Doris, oh Doris, what are we waiting for …?’

There was a pause, then Helen threw back her head and burst into laughter. ‘That’s hilarious!’

Ben grinned, and resumed work. ‘That’s what Doris thought. She couldn’t get over the cuspidor, didn’t think it romantic at all. She was a dancer – the longest legs you ever saw, and I was bursting to get her into bed. That’s pretty optimistic when you’re five-foot-five. Still, I gave her a good laugh.’

Helen giggled. ‘If I’d been Doris I’d have fallen for that one!’

Ben felt a flicker of hope. ‘Better be careful, I might think my luck’s changed and re-write it.’

Helen tried to stop giggling. ‘But have you seriously tried to write, Ben?’

The flicker faltered. Nothing like a hasty change of a subject like this to falter flickers.

‘I’ve made lots of notes every day. One day I’ll get my arse to an anchor for a few months and start it.’

‘And what will it be about?’

He was screwing the override switch into the wall. ‘Hemingway said you should only write about what you know. So my book will be about this little New York Jewish jeweller, oversexed and underloved, who chucks it all up in disgust and goes off to savour life as best he can.’

She grinned. ‘Oh, Ben …’ She was about to query the underloved playfully, but thought better of it. ‘Will it include this visit to the Outback?’

‘Oh yes.’ He paused and took a sip of wine. ‘You’ll be in it.’

She fluttered her eyelids tizzily. ‘Really? Dull old me?’ Then she narrowed her eyes theatrically. ‘What will it say about me, Smart-ass?’

Ben twisted his screwdriver, considering.

‘I assure you, Helen, that you’re not dull. You’re a very interesting woman.’

‘“Interesting”? You make me sound like a “case”! What kind of case of most interesting woman am I? A case of rather interesting bushwhacked mindlessness?’

He grinned at the wall. ‘You’re highly intelligent, Helen. And … appealing.’ He was going to say desirable, but changed it in his mouth.

‘Intelligent? I ain’t said anything intelligent yet. But I’m a humdinger when I get going. Ask Oscar, bless his soul …’ She sighed, then added glumly: ‘I haven’t done anything intelligent for twenty years.’

He had wasted the opening. ‘You’ve raised a lovely family.’

‘Any dumb blonde can do that. I mean intelligent.’ She banged her brow. ‘Something that requires the ability to grasp new concepts and apply them. Develop them. Create with them …’

He tightened the last screw, and stood up.

‘There. We’ll test it later.’ He turned to her. And this was the moment to make his pass at her: they were in the bedroom, and about to leave it. He felt just bold enough, with all the booze inside him. He was about to sit down on the bed beside her – and he lost his nerve. He said instead:

‘You’re right, of course, we could all do so much more with our brains. Have you ever thought of writing?’

‘What’s there for me to write about?’

The moment was definitely past, and he felt a kind of relief that he hadn’t made a premature blunder.

‘Write about you. Like Hemingway said. You’re what you know best. Write about being a woman. Your kind of woman, in your situation. It’s something that most women will understand and empathize with.’

‘Empathize with? How many women live in the Outback?’

It would have been absolutely natural to sit down on the bed beside her. But again he lacked the nerve. He said:

‘The Outback is only an extreme example of the condition in which many women – if not most women – find themselves in suburbia. All over the western world.’ He waved a finger. ‘They start a career. Then they get married and raise a family and the career is sacrificed to the drudgery of housework. The struggle to make ends meet. Meanwhile, the husband’s career goes on. He has the stimulus, the companionship, the promotions, the job-satisfaction. Finally the kids grow up and leave home. What’s Mum got left? Even her housewife’s job is virtually taken away. What does she do?’

Helen was staring up at him. ‘Right!’ she said emphatically, and took an aggressive swig of wine.

Her emphasis surprised even the optimist in him. Surely this was the moment to sit down beside her? He did so, three feet away, and marshalled his thoughts rapidly.

‘But you must write it as a story, Helen. Not as a poor-me autobiography. You must create verbal pictures the reader can see and feel. With a plot which makes the reader want to know what happens next, how the heroine handles this problem. Then …’ He raised his thick eyebrows. ‘Then you’ve created a worthwhile work of art, baby.’

Helen was hanging on wisdom. That familiar baby didn’t offend her this time. ‘And?’ she demanded. ‘What does our heroine do?’

Oh, indeed, what does she do? He said, cautiously: ‘Depends on who she is. You know yourself properly – I don’t.’ He decided to say it: ‘Maybe she has an affair? Many women do.’

‘But,’ she protested, ‘I could never do that, that wouldn’t be me! I’m supposed to write about me …’

Ben Sunninghill gave an inward sigh. Had he blown it? Hope winced and subsided into its shell. He tried to make himself sound academic:

‘But maybe your heroine does. Half the ladies bored out of their minds in suburbia would, and the other half would understand, even applaud.’

‘But an affair doesn’t solve her basic problem!’

Oh well … ‘That’s your task, as the story-teller – to show us what it does or doesn’t solve.’ He sighed and abandoned the subject of adultery. ‘Or maybe she takes a job – any job, because she’s too old now to resume her career. Or’ – he shrugged – ‘maybe she leaves. To go off and do her own thing, whatever that is.’

She said emphatically: ‘But she loves her husband! And her family!’

Oh dear. Hope curled up in its shell. ‘Ah, that’s the tricky part. One of the most difficult parts. Remember what I said about the price? The heartache? The loneliness? The financial hardship?’ He shrugged. ‘It’s your job as story-teller to make all this real for the reader.’

Helen looked at him unsteadily. ‘But what makes her leave her family? Her loved ones?’

Ben said: ‘But they’ve already left her, haven’t they?’

‘Yes, but only … physically. Geographically. They’re still a family.’

Ben shook his head. ‘Yes and no. That’s the whole point. The family goes on, sure, but it ain’t what it used to be. The story is how the heroine who’s left behind handles that problem. Look at your friends and ask yourself what you think their problem is. The details of it. And look at yourself.’ (It was on the tip of her tongue to protest that she didn’t have a problem.) Ben pointed at the photograph of Clyde, and for the moment he was entirely altruistic: ‘Ask yourself how your life with Clyde has changed – for better or worse – and why. Is there the same excitement of facing the future together? Obviously not, now is the future. What’s the difference between that excitement of yesteryear, those hopes, and the reality of now? How much disappointment is there?’ He looked at her earnestly. ‘What do you talk about these days? The same things you talked about twenty years ago when you were fresh from university and he was a horny young sheep-shearer desperate to carry you off to his mortgaged station?’ He shook his head. ‘No, of course not you’ve said all that: but have you … supplemented your conversations – together – so that you’ve still got things to talk about, to interest each other in? If not, why not? For example, do you both read good books, or only one of you? Do you even share the same interests now – or is it really only the common interest of survival?’ Helen was hanging on his words. ‘Yes, you love him, but not in the way you did when you first married him, when you were so crazy about him that you quit university. What does he mean to you now, Helen, twenty years on? And why? And is it enough, in all the circumstances, that you – or your heroine – must pay for it with the precious remnants of her youthfulness?’ He looked at her, and his altruism faltered. ‘What’s her sex-life like? Ask yourself what yours is like.’ Helen blinked. ‘Is it what it used to be twenty years ago, when you couldn’t get enough of each other? Of course not, nobody can keep up that enthusiasm. No, it’s changed, but to what?’ Helen blinked again. ‘Once a week, when he’s home – once a fortnight? Once a month? Why so seldom? Is it because you’re ageing? No. Is it because he’s ageing? No, he’d do three times a night with a new chick. So?’ He tapped his head. ‘So it’s up here.’ He leant out and tapped her head. ‘But what’s up here? Or in your heroine’s head? And what does she want to do about it, and how? That’s what the story-teller’s got to fascinate the reader with.’