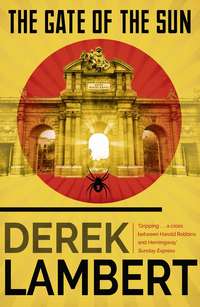

The Gate of the Sun

He knew that the Moors fighting for Franco took no prisoners and cut off their victims’ genitals; he knew that the heroine of the Republicans was a woman known as La Pasionaria.

He knew that on the sides of this carriage where, on the wooden seats, peasants sat with their live chickens and baskets of locust beans were scrawled the letters UGT and CNT and FAI, but he had no idea what they meant and was ashamed of his ignorance.

The plain rolled past; water and smuts from the labouring engine streaked the windows.

‘So what else have you found out?’ Tom asked Seidler.

‘That Albacete is the asshole of Spain but they make good killing knives there.’

The militiamen, Tom reflected later, had been right about Albacete. It was cold and commonplace, and the cafés were crammed with discontented members of the International Brigades from many nations drinking cheap red wine.

The garrison was worse. It was the colour of clay, the barrack-room walls were the graveyards of squashed bugs and the floors were laid with bone-chilling stone. Tom and Seidler were quartered with Americans in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion – seamen, students and Communists – but France was in the ascendancy: the Brigade commissar, André Marty, was a bulky Frenchman with a persecution complex; parade-ground orders were issued in French; many uniforms, particularly those worn resentfully by the British, were Gallic leftovers from other conflicts.

He and Seidler complained to Marty the day the commander of the Abraham Lincolns, good and drunk, fired his pistol through a barrack-room ceiling.

From behind his desk Marty, balding with a luxuriant moustache, regarded them suspiciously.

‘You are guests in a foreign country. You shouldn’t complain – just think of what the poor bastards in Madrid are going through.’

‘Sure, and we want to help them,’ Seidler said. ‘But the instructors here couldn’t organize a piss-up in a brewery.’

Marty fiddled with a button on his crumpled brown uniform.

‘You Jewish?’ He sucked his moustache with his bottom lip. ‘And a flier?’ – as though that compounded the crime.

And it was then that Tom Canfield realized that Marty was jealous, that fliers were different and that this would always be an advantage in life.

‘We didn’t come here to march and clean guns: we came here to fly,’ Tom said. He loved the word ‘fly’ and he wanted to repeat it. ‘We came here to bomb the Fascists at the gates of Madrid and shoot their bombers out of the sky. We’re not helping the Cause sitting on our asses; flying is what we’re good at.’

Marty, who was said to have the ear of Stalin, listened impatiently and Tom got the impression that it was Communism rather than the Cause that interested him.

‘I want your passports,’ Marty said.

‘The hell you do.’

‘In case you get shot down. You’re not supposed to be in this war. Article Ten of the Covenant of the League of Nations.’

‘So what about the Russians?’ Tom asked.

‘Advisers,’ Marty said. ‘Give me your passport.’

‘No way,’ Tom said. Then he said, ‘You mean we’re leaving here?’

‘To Guadalajara, north-east of Madrid. You’ll be trained by Soviet advisers. There’s a train this afternoon. On your way,’ said Marty who could do without fliers in his brigade. He flung two sets of documents on the desk. Tom was José Espinosa, Seidler Luis Morales. ‘Only Spaniards are fighting this war,’ Marty said. ‘It’s called non-intervention.’

‘Congratulations, Pepe,’ Seidler said outside the office.

‘Huh?’

‘The familiar form of José.’

Tom scanned his new identification paper. It was in French. Of course. But he still had his passport.

At the last minute the Heinkel from the Condor Legion, silver with brown and green camouflage, ace of spades painted on the fuselage, veered away. Tom didn’t blame the pilot: the Russian-made rats were plundering the skies. Or maybe the pilot was no more a Fascist than he was a Communist and could see no sense in joining battle with a stranger over a battlefield where enough men had died already.

He banked and flew above the dispersing mist, landing at Guadalajara, which the Republicans had captured early in the fighting. Seidler was playing poker in a tent with three other pilots in the squadron’s American Patrol. He was winning but he displayed no emotion; Tom had never heard him laugh.

Tom made his reconnaissance report to the squadron commander – he was learning Spanish but his tongue grew thick with trying – debating whether to mention the Heinkel. If he did the commander would want to know why he hadn’t pursued it.

‘No enemy aircraft?’ asked the commander who had already shot down 11.

‘One Heinkel 51,’ Tom said.

‘You didn’t chase it?’

Tom shook his head.

‘Very wise: he was probably leading you into an ambush.’

Tom fetched a mug of coffee and met Seidler walking across the airfield where Polikarpovs, Chato 1-15 biplanes and bulbous-nosed Tupolev bombers stood at rest. It was cold and weeping clouds were following the Henares river on its run from the mountains.

The trouble with this war in which brothers killed brothers and sons killed fathers, he thought as they walked towards their billet, was that nothing was simple. How could a foreigner be expected to understand a war in which there were at least 13 factions? A war in which the Republicans were divided into Communists and Anarchists and God knows what else. A Communist had recently told him that POUM, Trotskyists he had thought, was in the pay of the Fascists. Work that one out.

They reached the billet and Seidler poured them each a measure of brandy. Tom shivered as it slid down his throat. Then he lay on his iron bedstead and stared at his feet clad in fleece-lined flying boots; at least fliers could keep warm. He had once believed that Spain was a land of perpetual sunshine … Sleet slid down the window of the hut and the wind from the mountains played a dirge in the telephone lines.

Seidler sat on the edge of his own bed, placing his leather helmet and goggles gently on the pillow; only Tom knew the secret of those goggles – the frames contained lenses to compensate for his bad sight.

He stared short-sightedly at Tom and said, ‘So how’d it go?’

‘Okay, I guess.’ He told Seidler, who had already recorded one kill, a Junkers 52 on a bombing mission, about the Heinkel. ‘I’m not sure I wanted to shoot it down.’

‘Know what I felt when I got that Junkers? I thought it was one of those passenger planes in a movie, you know, when Gary Cooper or Errol Flynn is trying to guide it through a storm. And as it caught fire and went into its death dive I thought I saw passengers at the windows. And then I thought that maybe it wasn’t a bomber because those Ju-52s are used as transport planes, too – 17 passengers, maybe more – and maybe I had killed them all. Kids younger than us, maybe.’

‘What you’ve got to do,’ Tom said, ‘is remember what we’re fighting for.’

‘I sometimes wonder.’

‘The atrocities …’

‘You mean our guys, the good guys, didn’t commit any?’

Tom was silent. He didn’t know.

‘In any case,’ Seidler said, ‘I’m supposed to be commiserating with you.’ He poured more brandy. ‘I hear that the Fascists have got a bunch of Fiat fighter planes with Italian crews. And that the Italians are going to launch an attack on Guadalajara.’

‘Where do you hear all these things?’

‘From the Russians,’ Seidler said.

‘You speak Russian?’

‘And Yiddish,’ Seidler said. The hut was suddenly suffused with pink light. ‘Here we go,’ Seidler said as the red alert flares burst over the field.

‘In this?’ Tom stared incredulously at the sleet.

They ran through the sleet which was, in fact, slackening – a luminous glow was now visible above the cloud – and climbed into the cockpits of their Polikarpovs. Tom knew that this time he really was going to war and he wished he understood why.

The Jarama is a mud-grey and thoughtful river that wanders south-east of Madrid in search of guidance. It had given its name to the battle being fought in the valley separating its guardian hills, their khaki flanks threaded in places with crystal, but in truth the fight was for the highway to Valencia which crosses the Jarama near Arganda. On this morose morning in February the Fascists dispatched an armada of Junkers 52s to bomb the bridge carrying this highway over the river.

Tom Canfield saw them spread in battle order, heavy with bombs, and above them he saw the Fiats, the Italians’ biplanes which Seidler had forecast would put in an appearance. He pointed and Seidler, flying beside him, peering through his prescription goggles, nodded and raised one thumb.

The Fiats were already peeling off to protect their pregnant charges and the wings were beating again in Tom Canfield’s chest. He gripped the control column tightly. ‘But what are you doing here?’ he asked himself. ‘Glory-seeking?’ Thank God he was scared. How could there be courage if there wasn’t fear? He waited for the signal from the squadron commander and, when it came, as the squadron scattered, he pulled gently and steadily on the column; soaring into the grey vault, he decided that the fear had left him. He was wrong.

The Fiat came at him from nowhere, hung on behind him. Bullets punctured the windshield. A Russian trainer had told him what to do if this happened. He had forgotten. He heard a chatter of gunfire. He looked behind. The Fiat was dropping away, butterflies of flame at the cowling. Seidler swept past, clenched fist raised. No pasarán! Seidler two, Canfield zero. He felt sick with failure. He kicked the rudder pedal and banked sharply, turning his attention to the bombers intent on starving Madrid to death.

Below lay the small town of San Martín de la Vega, set among the coils of the river and the ruler-straight line of a canal. He saw ragged formations of troops but he couldn’t distinguish friend from foe.

The anti-aircraft fire had stopped – the deadly German 88 mm guns could hit one of their own in this crowded sky – and the fighters dived and banked and darted like mosquitoes on a summer evening.

Tom saw a Fiat biplane with the Fascist yoke and arrows on its fuselage diving on a Polikarpov. As it crossed his sights he pressed the firing button of his machine-guns. His little rat shuddered. The Fiat’s dive steepened. Tom watched it. He bit the inside of his lip. The dive steepened. The Fiat buried its nose in a field of vines, its tail protruding from the dark soil. Then it exploded.

Tom was bewildered and exultant. And now, above a hill covered with umbrella pine, he was hunting, wanting to shoot, wasting bullets as the Fiats escaped from his sights. So close were they that it seemed that, if the moments had been frozen, he could have reached out and shaken the hands of the enemy pilots. But it had been a mistake to try and get under the bombers; instead he attacked them from the side. He picked out one, a straggler at the rear of his formation. A machine-gun opened up from the windows where Seidler had imagined passengers staring at him; he flew directly at the gun-snarling fuselage, fired two bursts and banked. The Junkers began to settle; a few moments later black smoke streamed from one of its engines; it settled lower as though landing, then, as it began to roll, two figures jumped from the door in the fuselage. The Junkers, relieved of their weight, turned, belly up, turned again, then fell flaming to the ground. Parachutes blossomed above the two figures.

Without looking down he saw again the white, naked faces of Spaniards killing each other, and reminded himself that among them were Americans and Italians and British and Russians, and wondered if the Spaniards really wanted the foreigners there, if they would not prefer to settle their grievances their own way, and then a Fiat came in from a pool of sunlight in the cloud and raked his rat from its gun-whiskered nose to its brilliant tail.

The Polikarpov was a limb with severed tendons. Tom pulled the control column. Nothing. He kicked the rudder pedal. Nothing. Not even the landing flaps responded. One of his arms was useless, too; it didn’t hurt but it floated numbly beside him and he knew that it had been hit. The propeller feathered and stopped and the rat began its descent. With his good hand Tom tried to work the undercarriage hand-crank, but that didn’t work either. Leafless treetops fled behind him; he saw faces and gun muzzles and the wet lines of ploughed soil.

He pulled again on the column and there might have been a slight response, he couldn’t be sure. He saw the glint of crystal in the hills above him; he saw the white wall of a farmhouse rushing at him.

CHAPTER 2

Ana Gomez was young and strong and black-haired and, in her way, beautiful but there was a sorrow in her life and that sorrow was her husband.

The trouble with Jesús Gomez was that he did not want to go to war, and when she marched to the barricades carrying a banner and singing defiant songs she often wondered how she had come to marry a man with the spine of a jellyfish.

Yet when she returned home to their shanty in the Tetuan district of Madrid, and found that he had foraged for bread and olive oil and beans and made thick soup she felt tenderness melt within her. This irritated her, too.

But it was his gentleness that had attracted her in the first place. He had come to Madrid from Segovia because it had called him, as it calls so many, and he worked as a cleaner in a museum filled with ceramics and when he wasn’t sweeping or delicately dusting or courting her with smouldering but discreet application he wrote poetry which, shyly, he sometimes showed her. So different was he from the strutting young men in her barrio that she became at first curious and then intrigued, and then captivated.

She worked at that time as a chambermaid in a tall and melancholy hotel near the Puerta del Sol, the plaza shaped like a half moon that is the centre of Madrid and, arguably, Spain. The hotel was full of echoes and memories, potted ferns and brass fittings worn thin by lingering hands; the floor tiles were black and white and footsteps rang on them briefly before losing themselves in the pervading somnolence.

Ana, who was paid 10 pesetas a day, and frequently underpaid because times were hard, was arguing with the manager about a lightweight wage packet when Jesús Gomez arrived with a message from the curator of the museum who wanted accommodation for a party of ceramic experts in the hotel. Jesús listened to the altercation, and was waiting outside the hotel when Ana left half an hour later.

He gallantly walked beside her and sat with her at a table outside one of the covered arcades encompassing the cobblestones of the Plaza Mayor and bought two coffees served in crushed ice.

‘I admired the way you stood up to that old buzzard,’ he said. He smiled a sad smile and she noticed how thin he was and how the sunlight found gold flecks in his brown eyes. Despite the heat of the August day he wore a dark suit, a little baggy at the knees, and a thin, striped tie and a cream shirt with frayed cuffs.

‘I lost just the same,’ she said, beginning to warm to him. She admired his gentle persistence; there was hidden strength there which the boy to whom she was tacitly betrothed, the son of a friend of her father’s, did not possess. How could you admire someone who pretended to be drunk when he was still sober?

‘You should ask for more money, not complain that you have been paid less.’

‘Then I would be sacked.’

‘Then you should complain to the authorities and there would be a strike in all the hotels and a general strike in Madrid. We shall be a republic soon,’ said Jesús, giving the impression that he knew of a conspiracy or two.

Much later she remembered those words uttered in the Plaza Mayor that summer day when General Miguel Primo de Rivera still ruled and Alfonso XIII reigned; how much they had impressed her, too young even at the age of 22 to recognize them for what they were.

‘My father says we will not be any better off as a republic than we are now.’ She sucked iced coffee through a straw. How many centimos had it cost him in this grand place? she wondered.

‘Then your father is a pessimist. The monarchy and the dictatorship will fall and the people will rule.’

On 14 April 1931, a republic was proclaimed. But then the Republicans, who wanted to give land to the peasants and Catalonia to the Catalans and a living wage to the workers and education to everyone, fell out among themselves and, in November 1933, the Old Guard, rallied by a Catholic rabble-rouser, José Maria Gil Robles, returned to power. Two black years of repression followed and a revolt by miners in Asturias in the north was savagely crushed by a young general named Francisco Franco.

But at first, in the late 20s, before Primo de Rivera quit and the King fled, Ana and Jesús Gomez were so absorbed in each other that, despite the heady predictions of Jesús, they paid little heed to the fuses burning below the surface of Spain; in fact it wasn’t until 1936 that Ana discovered her hatred for Fascists, employers, priests, anyone who stood in her way.

When Jesús proposed marriage Ana accepted, ignoring the questions that occasionally nudged her when she lay awake beside her two sisters in the pinched house at the end of a rutted lane near the Rastro, the flea-market. Why after nearly a year was he still earning a pittance in the perpetual twilight of the museum whereas she, at his behest, had demanded a two-peseta-a-day pay rise and been granted one by an astounded hotel manager? Why did he not try to publish the poems he wrote in exercise books? Why did he not join a trade union, because surely there was a place for a museum cleaner somewhere in the ranks of the CNT or UGT?

They were married during the fiesta of San Isidro, Madrid’s own saint. The ceremony, attended by a multitude of Ana’s family, and a handful of her fiancé’s from Segovia, was performed in a frugal church and cost 20 pesetas; the reception was held in a café between a tobacco factory and a foundling hospital owned by the father of Ana’s former boyfriend, Emilio, who fooled everyone by getting genuinely drunk on rough wine from La Mancha.

Emilio, whose black hair was as thick as fur, and who had been much chided by his companions for allowing the vivacious and wilful Ana to escape, accosted the bridegroom as he made his way with his bride to the old Ford T-saloon provided by Ana’s boss. He stuck out his hand.

‘I want to congratulate you,’ he said to Jesús. ‘And you know what that means to me.’ He wore a celluloid collar which chafed his thick neck and he eased one finger inside it to relieve the soreness.

Jesús accepted the handshake. ‘I do know what it means to you,’ he said. ‘And I’m grateful.’

‘How would you know what it means to me?’ Emilio tightened his grip on the hand of Jesús, becoming red in the face, though whether this was from exertion or wine circulating in his veins was difficult to ascertain.

‘Obviously it must mean a lot,’ Jesús said, trying to withdraw his hand.

Ana, who had changed from her wedding gown into a lemon-yellow dress, waited, a dry excitement in her throat. The three of them were standing between the café where the guests were bunched and the Ford where the porter from the hotel stood holding the door open. No-man’s-land.

‘It means a lot to me,’ Emilio said thickly, ‘because Ana promised herself to me.’

‘Liar,’ Ana said.

‘Have you told him what we did together?’

‘We did nothing except hang around while you pretended to get drunk.’ What she had seen in Emilio she couldn’t imagine. Perhaps nothing: their union had been decided without any reference to her.

Emilio continued to grip the hand of Jesús, the colour in his cheeks spreading to his neck. Jesús had stopped trying to extricate his hand and their arms formed an incongruous union, but he showed no pain as Emilio squeezed harder.

The group outside the café stood frozen as though posing for a photographer who had lost himself inside his black drape.

‘We did a lot of things,’ Emilio grunted.

The porter from the hotel, who wore polished gaiters borrowed from a chauffeur and a grey cap with a shiny peak, moved the door of the Ford slowly back and forth. Fireworks crackled in the distance.

Jesús, thought Ana, will have to hit him with his left fist – a terrible thing to happen on this day of all days but what alternative did he have?

Jesús smiled. Smiled! This further aggrieved Emilio.

‘You would be surprised at the things we did,’ he said squeezing the hand of Jesús Gomez until the knuckles on his own fist shone white.

Finally Jesús, his smile broadening with the pleasure of one who recognizes a true friend, said, ‘Emilio, I accept your congratulations, you are a good man,’ and began to shake his imprisoned hand up and down.

‘Cabrón,’ Emilio said.

‘God go with you.’

‘Piss in your mother’s milk.’

‘Your day will come,’ Jesús said, a remark so enigmatic that it caused much debate among the other guests when they returned to their wine.

The two men stared at each other, hands rhythmically rising and falling, until finally Emilio released his grip and, massaging his knuckles, stared reproachfully at Jesús Gomez.

Jesús saluted, one finger to his forehead, turned, waved to the silent guests, proffered his arm to his bride and led her to the waiting Ford.

From the bathroom of the small hostal near the Caso de Campo, she said, ‘You handled that Emilio very well. He is a pig.’

She took the combs from her shining black hair and shed her clothes and looked at herself in the mirror. In the street outside a bonfire blazed and couples danced in its light. Would he ask her about those things that Emilio claimed they had done together?

‘Emilio’s not such a bad fellow,’ Jesús said from the sighing double bed. ‘He was drunk, that was his trouble.’

Didn’t he care?

‘He is a great womanizer,’ Ana said.

‘I can believe that.’

‘And a brawler.’

‘That too.’

She ran her hands over her breasts and felt the nipples stiffen. What would it be like? She knew it wouldn’t be like the smut that some of the married women in the barrio talked while their husbands drank and played dominoes, not like the Hollywood movies in which couples never shared a bed but nevertheless managed to produce freckled children who inevitably appeared at the breakfast table. She wished he had hit Emilio and she knew it was wrong to wish this.

In novels, the bride always puts on a nightdress before joining her husband in the nuptial bed. To Señora Ana Gomez that seemed to be a waste of time. She walked naked into the white-washed bedroom and when he saw her he pulled back the clean-smelling sheet; she saw that he, too, was naked and, for the first time, noticed the whippy muscles on his thin body, and in wonderment, and then in abandonment, she joined him and it was like nothing she had heard about or read about or anticipated.

It is true that Ana Gomez only encountered her hatred during the Civil War, but it must have been growing sturdily in the dark recesses of her soul to show its hand so vigorously.

When, slyly, was it conceived? In the black years, when one of her three brothers was beaten up by police, losing the sight of one eye, for rallying the dynamite-throwing miners of Asturias? When, at the age of 62, her father, a gravedigger, bowed by years of accommodating the dead, was sacked by the same priest who had married her to Jesús for taking home the dying flowers from a few graves? Or because the same fat-cheeked incumbent had declined to baptize her first-born, Rosana, because she had not attended mass regularly, although for a donation of 20 pesetas he would reconsider his decision … Ah, those black crows who stuffed the rich with education and starved the poor. Ana believed in God but considered him to be a bad employer.