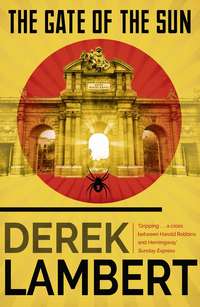

The Gate of the Sun

‘So why,’ he asked in English, ‘were two mercenaries fighting on opposite sides sharing a shell-hole?’

‘I guess you could call it force of circumstances,’ Tom Canfield said.

‘It does neither of you any credit. What is your name?’ he asked Canfield.

‘You’ve got it there in front of you. José Espinosa.’

‘Your real name: non-intervention is a stale joke.’

‘Okay, what the hell – Thomas Canfield.’

‘Why are you fighting for the rabble, Señor Canfield?’

‘Name, rank and number. Nothing more. Isn’t that right, Colonel?’

The glossy captain pulled his long-barrelled pistol from its holster. ‘Answer the colonel,’ he said.

‘You don’t have a rank or number,’ Delgado said.

‘José Espinosa does.’

‘Are you Jewish?’

‘Espinosa, José, pilot, 3805.’

‘This isn’t a movie, Señor Canfield. Please enlighten me: I cannot understand – really I can’t – why any reasonable man should want to fight for a ragged army of peasants and city hooligans whose sport is burning churches and murdering anyone industrious enough to have earned more money than them.’

‘Then you don’t understand very much, Colonel.’

‘Anti-Hitler? Anti-Mussolini? Anti-Fascist?’

‘Anti-gangster,’ Tom said.

‘So we have one anti-Fascist.’ Delgado turned to Adam Fleming who was standing, legs apart, hands clasped behind his back, beside Canfield. ‘And one anti-Communist. Do you both find Spain an agreeable location to indulge your politics?’

‘Your politics, sir,’ Adam said.

‘Nice climate,’ Tom said.

Delgado lit an English cigarette, a Senior Service. ‘You, I presume,’ he said to Canfield, ‘were trying to find your way back to the Republican lines.’

‘Wherever those are,’ Tom said.

‘And you,’ to Fleming, ‘were hiding from an unexploded shell?’

‘I got lost,’ Adam said.

‘Perhaps we should provide foreign mercenaries with compasses as well as rifles.’

‘Good idea,’ Tom said. ‘They might find the right side to fight for.’

The captain prodded him in the back with the barrel of his pistol.

Delgado blew a jet of smoke across the bunker. It billowed in the light of the hurricane lamps.

‘So what shall I do with the two of you? One American fighting for the enemy, one Englishman displaying cowardice in the face of the enemy …’

‘That’s a lie,’ Adam said.

‘He was concussed,’ Tom said.

‘Your loyalty is touching. But loyalty to what, an anti-Communist?’

‘I’m not a Communist,’ Tom said.

‘Then it is you who is serving on the wrong side.’ Delgado smoked ruminatively and precisely. ‘There are a lot of misguided men fighting for the Republicans. Good officers in the Fifth Regiment, like Lister and Modesto and El Campesino, of course. When he was only 16 he blew up four Civil Guards. Then he fought in Morocco – on both sides! Would you consider flying for us, Señor Canfield?’

‘You’ve got to be kidding,’ Tom said.

‘I rarely joke,’ Delgado said. ‘I see no point to it. But I’m glad you’re staying loyal to the side you mistakenly chose to fight for.’ He dropped his cigarette on the floor, squashing it with the heel of one elegant boot. ‘Now all that remains is to decide the method of execution.’

Spray broke over the prow of HMS Esk as it knifed its way through the swell on its approach to Marseilles but Martine Ruiz, standing on the deck with her five-year-old daughter, Marisa, didn’t seem to notice it as it brushed her face and trickled in tears down her cheeks.

What concerned her was the future that lay ahead through the spume and the greyness for herself, Marisa and her three-day-old baby. How could she settle in England?

What would she do without Antonio? Why did he have to fight when all that had been necessary was to slip away to some Fascist-held city such as Seville or Granada in the south or Salamanca or Burgos in the north and lie low until Madrid was captured? She wished dearly that Antonio was here beside her so that she could scold him.

She stumbled across the lurching deck and went below. Her breasts hurt and her womb ached with emptiness.

The baby was as she had left it in a makeshift cot, a drawer padded with pillows; Able Seaman Thomas Emlyn Jones was also as she had left him, sitting beside the drawer on the bunk reading a copy of a magazine called Razzle.

He hastily folded the magazine and placed it on the bunk beneath his cap.

‘Not a sound,’ he said. ‘Not a dicky bird.’ He stared at his big, furry hands. ‘I was wondering … How are you going to get to England?’

‘Train,’ she said. ‘Then ferry.’

‘Lumbering cattle trucks, those ferries. You mind she isn’t sick,’ pointing to the sleeping baby.

Martine glanced at herself in the mirror. There were shadows under her eyes and her face was drained.

‘It is me who will be sick.’ She spoke English slowly and with care.

‘And me,’ Marisa said. She lay on the bunk and closed her eyes.

‘You’d be surprised how many sailors are sea-sick,’ Taffy Jones said.

Martine, who was becoming queazy, stared curiously at his chapel-dark features. ‘What part of England do you come from?’ she asked.

‘England is it?’ His reaction was unexpected and, she suspected, ungrammatical.

She stared at him uncomprehendingly. ‘Aren’t you English?’

‘Is the Pope a Protestant? I come from Wales, girl, and don’t you ever forget it.’

Now she understood. He was just like a Basque, she thought. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘It’s me that should be sorry, bloody fool that I am.’ He looked at his hands, clenching them and unclenching them, and then he looked at the baby. ‘I was thinking,’ he said, ‘when you get to England … Do you have anywhere to go?’

‘A relative,’ thinking of her brother Pierre who worked in the Credit Lyonnais in London.

‘Ah, not too bad then.’ He adjusted the pillow behind the baby’s head. ‘But just in case this relative of yours is too distant, if you’re ever stuck … You know, if you don’t have anywhere to go you could always come and see us in Wales.’ He handed her a lined sheet of paper. ‘There’s the address, just in case.’ He stood up awkwardly.

Martine took the scrap of paper. ‘Thank you Monsieur Jones.’

‘Taffy.’

‘Monsieur Taffy. And now,’ she said, as the baby stirred and prepared its face to cry, ‘I must feed her.’

Taffy Jones picked up his cap and his copy of Razzle. ‘What are you going to call her?’ he said. ‘I meant to ask you.’

‘Isabel.’

‘Can she have another name?’

‘As many as she wants,’ Martine said.

‘My name’s Thomas. I thought maybe Thomasina might be a good name. How does it sound in Spanish?’

‘It sounds like Tomasina,’ Martine said. ‘And now if you’ll excuse me.’

Isabel Tomasina began to whimper and at first the sounds were so small that to Taffy Jones they sounded like the lonely cries of the seagulls wheeling overhead.

It was dawn – the classic time for executions. Tom Canfield and Adam Fleming walked under armed guard. Behind them were Delgado and the young captain.

Mist lay in the valley but here in a field of vines the air was clean and still night-smelling. A squadron of Capronis flew high above Pingarrón.

Adam glanced at Canfield. He looked thoughtful, that was all, thoughtful and, with his fair hair and lazily dangerous face, very American, convinced that he would be welcome anywhere in the world and if not he would want to know the reason why.

Not any more, Tom Canfield, we are going to die, you and I. For what? For bringing our contradictory ideals to a foreign land?

He stumbled over a fiercely pruned vine. He looked back. The vines squatted in the wet earth like a graveyard of crosses.

There is no future. Life is an entity, not a sequence. It is mine and when it is severed there will be no life for anyone because it is I who see and hear. No life for you, Colonel Delgado, slicing the enemy bristles from your cheeks with a cut-throat razor; no promotion for you, Captain, so handy with your long-barrelled pistol, certainly no life for you, Tom Canfield, who dropped into my life just 12 hours ago.

They approached a ruined farmhouse. A whitewashed wall was still standing and there were blood stains and the pock marks of bullets on it.

Adam Fleming opened his mouth and screamed but no sound issued from his lips.

Canfield said, ‘Excuse me, Colonel, may I ask you a question?’

Delgado switched irritably with his cane at a clump of nettles. ‘What is it?’

‘Will you grant a last request?’

‘What is it?’

‘Don’t shoot me.’

‘You have a sense of humour,’ Delgado said. ‘Why else would you be fighting for Republicans?’

Adam noticed that Canfield’s lips were tight and a muscle was moving in the line of his jaw. They stopped in front of the wall beneath a flap of bamboo roof. Where was the firing squad?

Delgado, holding his cane between two hands, turned and faced them. ‘You,’ to Canfield, ‘will be executed because you were found wearing civilian clothes and carrying false papers. You,’ – to Adam – ‘should be executed for desertion.’

Should?

‘But I am willing to concede you were shell-shocked. However, you know my views on foreign mercenaries meddling in Spain’s war. It seems logical, therefore, that you should carry out the execution.’ The captain handed Adam the pistol. ‘After all, he is the enemy.’

Adam took the gun. It had been tended with love, and he knew the mechanism would work snugly.

Delgado pointed at the blood-stained wall with his cane. ‘Over there.’ The blood stains were the colour of rust. ‘Do you want to be blindfolded?’ he asked Canfield.

‘I like to look the enemy in the eye. One of the lessons you learn in boxing.’ There was a catch in his voice and his body was shaking and because they had known each other a long time, 12 hours at least, Adam knew that he was thinking, ‘Please, God, don’t let me be a coward.’

Cowardice? Who cared about cowardice? Why did they teach children that it mattered? If I live I will teach children that cowardice is natural, the most natural thing in the world; but I shan’t live because I can’t shoot Tom Canfield.

‘If you refuse,’ Delgado was saying, ‘you, too, will be executed for desertion, for refusing to obey an order, for cowardice.’

There it was again, cowardice. I wish I could pin medals on the breasts of all those who have exhibited cowardice in the face of the enemy. I wish I could tell my children that they should never be ashamed of crying.

‘There.’ Delgado indicated a line whitewashed on the mud. ‘Get it over with quickly: we are due to attack again.’

The sound of aircraft filled the sky. Adam looked up. Russian-built Katiuska twin-engined bombers.

‘Get on with it,’ Delgado snapped.

Adam raised the pistol.

‘I will raise my cane,’ Delgado said. ‘When I drop it you will fire. Empty the barrel, just in case.’

Adam stared down the barrel of the pistol, lined up Canfield’s chest with the inverted V blade foresight and the V notch rearsight. Why shouldn’t I shoot him? He is the enemy, a red, and I have killed many of those already.

Canfield said, ‘How about that …’ He lost his sentence, recaptured it. ‘… last request? A cigarette?’

You don’t smoke, Adam thought. He stroked the trigger. Two pressures? Why do you hesitate, Adam Fleming? Canfield chose to fight on that side, you on this. You came to Spain to kill reds, didn’t you? Priest-killers, murderers of your sister’s husband.

Who is the enemy?

‘Permission refused.’ Delgado’s cane fell.

The last thing Adam Fleming remembered was the roar of a Katiuska bomber.

Tom Canfield assumed he was dead.

The crash and the pointed ache in his skull and the crepitus of fractured wall … Now all he could see was a khaki-coloured dustiness. Perhaps he was in the process of dying. He tested his limbs. They moved painlessly, all except the arm that had been wounded in the plane crash. His hand went to his chest searching for bullet holes. Nothing. The dust began to clear. He heard a groan. He sat up.

The flap of bamboo lay across his knees. Then he heard the drone of the Katiuska bombers.

He stood up and blundered through the settling dust. The first body he encountered was Delgado’s. He was still alive but for once he did not look freshly barbered. Then the two soldiers and the captain. One of the soldiers was dead. Lastly Adam Fleming, pistol still clenched in his fist. There was a wound on the side of his head and his face was grey.

He knelt beside him. He was alive but only just. His breathing was shallow and blood flowed freely from the scalp wound. Tom took a torn cushion from a cane chair, placed it under his head and tried to staunch the bleeding with his handkerchief.

‘Were you going to shoot me?’ he asked the unconscious man. ‘Would I have shot you?’

He heard voices. He knelt behind a heap of rubble beside a legless rubber doll. Fascist soldiers were approaching. They would look after Fleming.

He took the pistol from his hand and edged round the remnants of the farmhouse. As he ran towards an olive grove he heard a noise behind him. He flung himself to the ground and the brown and white dog with the foraging nose licked his face, then whipped his chest with its long tail.

‘Another survivor,’ Tom said. He patted the dog’s lean ribs. ‘Come on, let’s find some breakfast.’

The hill where Adam Fleming had been fighting lay ahead. He began to climb towards the Republican lines on the other side.

Machine-gun fire chattered in the distance but yesterday’s battlefield was deserted except for corpses. The sky was pure and pale, and the mist in the valley was rising. It was going to be a fine, spring-beckoning day.

He was near the brow of the hill now. There he would be a silhouette, a perfect target. He flattened himself on the shell-torn ground and, with the dog beside him, inched upwards.

Bodies lay stiffly around him, many of them British by the look of them, wearing berets and Balaclavas and job-lot uniforms, staring at the sky as though in search of reasons.

At the crest of the mole-shaped hill he rolled towards the Republican lines. Hit a rock and lay still. When he tried to stand up there was no strength in him. He noticed blood from his wounded arm splashing on to a slab of stone. How long had it been bleeding like that? Pain knifed his chest.

The dog whined, whip-lash tail lowered.

He continued down the hill, cannoning into ilex trees, slithering in the water draining from the top of the hill. There was a dirt road at the bottom and he had to reach it. He collapsed into a fragrant patch of sage 50 metres short of it. He stretched out one hand and felt the dog. Or is this all an illusion? Did Adam Fleming pull the trigger?

The smell of the sage and the warmth of the dog faded.

It was replaced by the smell of ether.

He opened his eyes. A middle-aged man with pugnacious features, Slavonic angles to his eyes and sparse grey hair, stood beside his bed.

The man said, ‘Please, don’t say Where am I.’

‘Okay, I won’t.’ He heard his own voice; it was thin and far away.

‘You’re in a field hospital. A monastery, in fact. And you’re extremely lucky to be alive for two reasons.’

‘Which are?’

‘A peasant found you bleeding to death near a dirt road. He stopped the bleeding by tying a strip of your shirt round your arm, pushing a stick underneath it and twisting it. A primitive tourniquet.’

‘Secondly?’

‘Then I drove by and saved your life.’

Tom closed his eyes. He was vaguely aware of something intrusive in his good arm. He tried to find it but he couldn’t move his other arm. He retreated into a star-filled sky.

‘Why did you come to Spain?’ Tom asked Dr Norman Bethune from Montreal when he next stood at his bedside.

‘I needed a war,’ Bethune said. ‘To see if I can save lives in the next one.’

‘Which next one would that be?’

‘The one we’re rehearsing for,’ said Bethune who was taking refrigerated blood to the front line instead of waiting for haemorrhaging casualties to reach hospitals. ‘How are you feeling?’

‘I wouldn’t want to go three rounds with Braddock but I’m okay, I guess. Whose blood have I got inside me?’ He jerked his head at the pipe protruding from his arm.

‘God knows. Good blood by the look of you. Maybe you owe your life to a priest.’

‘Don’t tell the commissar that,’ Tom said. ‘Are these all your patients?’ He pointed at the broken and bandaged patients lying on an assortment of beds in the stone-floored dining hall of the monastery.

‘A few, those with colour in their cheeks. I gave the first transfusion at the front on 23 December last year. Remember that date: maybe it will be more important than the date the war broke out.’

Tom raised himself on his pillow, then said abruptly, ‘When can I fly again?’

‘When your arm’s mended. You broke it a few days ago. Right?’

‘I got shot down.’

‘And later you must have fallen. And when you fell you turned a simple fracture into a compound fracture and a splinter of bone penetrated an artery and the haemorrhage became a deluge.’

‘I can fly with my left hand.’

‘When your ribs are mended.’

‘Ribs?’

Bethune pointed at his chest. ‘They weren’t practising first-aid when they strapped you up.’

‘Shit,’ said Tom Canfield. ‘No pain though.’

‘Breathe in deeply.’

‘Shit,’ said Tom Canfield.

During the next five days Tom fell in love and learned how to acquire a fortune.

The girl’s name was Josefina. She was 18 and stern in the fashion of nurses, although sometimes the touch of her fingers was shy. She was a student nurse, qualified by war, and she came from a small coastal town astride the provinces of Valencia and Alicante.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов