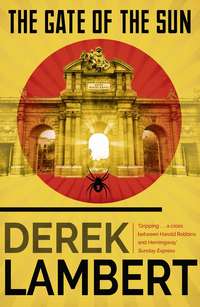

The Gate of the Sun

Tom smiled. A bullet hit a tree hanging over the river gouging a finger of sappy wood from it. He dropped to the ground, took cover behind another farmhouse with a patio scattered with olive stones. There was some bread on a scrubbed table and a leather wineskin. The bread was stale but not too hard; he ate it and drank sweet dark wine from the wineskin. The wine intoxicated him immediately.

He heard a dog barking. He opened a studded door with a rusty key in the lock. The dog was half pointer, half hunter, with a whiplash tail, brown and white fur, a brown nose and yellowish eyes. It was young, starving and excited; as Tom stroked its lean ribs it pissed with excitement. Tom gave it the last of the bread.

A heavy machine-gun opened up; bullets thudded into the walls of the patio. The lingering Polikarpov returned, firing a burst in the direction of the machine-gun. Seidler without a doubt. The machine-gun stopped firing but Tom decided to leave the farmhouse which was a natural target. He let himself out of the patio. The dog followed.

The river led him through the rain into mist. He came to a broken bridge that had been blown up, coming to rest where it had originally been built. He ran across it, the dog at his heels.

The gunfire was louder now. No chance yet of getting through the Fascist lines. He noticed a shell-hole partly covered by a length of shattered fencing. He slithered down the side, coming to rest opposite a young, dark-haired soldier dazed with battle.

Sometimes a meeting between two people is a conceiving. A dual life is propagated and it possesses a special lustre even when its partners are divided by time or location. These partners, although they may fight, are blessed because together they may glimpse a vindication of life. All of this passes unnoticed at the time; all, that is, except an easiness between them.

Tom Canfield became aware of this easiness when, coming face to face with Adam Fleming in a shell-hole in the middle of Spain, he said, ‘Hi, soldier,’ and Adam replied incredulously, ‘I can hear you.’

And because a sense of absurdity is companion of these relationships, Tom laughed idiotically and said, ‘You can what?’

‘Hear you. I was deaf until you dropped in.’ And then he, too, began to laugh.

Tom watched him until the laughter was stilled. He had an argumentative face and, despite the laughter, his eyes were wide with shock. Tom was glad he was a flier: these young men from the debating forums of Europe hadn’t been prepared for the brutality of a battlefield.

‘Where did you learn to shoot?’ he asked pointing at the Russian rifle in the young man’s hands.

‘At college.’

‘In England? I thought you only learned cricket.’

‘And tennis. I played a lot of tennis.’

‘Because you were supposed to play cricket?’

‘You’re very perceptive. My name’s Adam Fleming.’ He saluted across the muddy water at the bottom of the crater.

‘Tom Canfield. How’s it going up there?’ he asked, nodding his head at the lowering sky.

Adam shrugged.

‘Fifty-fifty. I got disorientated,’ he said as though an explanation was necessary. ‘I didn’t know who I was fighting. Maybe someone fired a rifle too close to my ear. I felt as though I had been punched.’

‘I know the feeling,’ Tom said.

‘You’re a boxer?’

‘A mauler.’ Tom hesitated. ‘What made you come out here?’ He cradled his wounded arm inside his flying jacket; the dog settled itself at his feet and closed its eyes.

‘The same as you probably. It’s difficult to put in words.’

‘I would have guessed you were pretty neat with words.’

‘I knew a great injustice was being perpetrated. I knew words weren’t enough; they never are. And you have to make your stand while you’re young … I’m not very good with words tonight,’ he said.

‘I guess you’ve been fighting too long,’ Tom said.

A shell burst overhead. Hot metal hissed in the water.

Adam said, ‘My father had a cartoon in his study. It was by an artist from the Great War called Bruce Bairnsfather. It showed two old soldiers sitting in a shell-hole just like this and one soldier is saying to the other, “If you knows of a better ’ole go to it.”’

‘This is the best hole I know of,’ Tom said.

‘You’re lucky, being a flier.’

‘A privileged background,’ Tom said. ‘My old man owned a Cessna.’

Fleming, he decided, came from London; a left-wing intellectual rather than an enlightened slogger like himself.

Adam said, ‘You haven’t told me what you’re doing here.’

‘It’s a weird thing to say but there was no other choice.’

‘I understand that. Did you ever doubt?’

‘My motives? Sure I did. I figure there’s a bit of the adventurer or the martyr in any foreigner fighting here.’

‘But our motives, surely, are stronger than self glory or self pity?’ His voice sounded anxious.

‘Oh sure. In my case anyway. I can’t speak for everyone. There are a few phonies here, you know.’

‘You think I’m one?’

‘I think you go looking for arguments.’

‘I can’t stand dogma. But you’re right, I’m too argumentative. It had me worried for a while. I wondered whether I was championing a cause out of perversity.’

‘Not you,’ Tom said. He had known this man for a long time – the frown as he interrogated himself, the dawning smile as he called his own bluff.

‘Then I had a letter from my sister.’

Tom waited; there is a time for waiting and when you knew someone as well as he knew Adam Fleming you knew that this was just such a time.

‘They killed her husband.’

‘Bastards.’

‘Then I knew I had to come here. I wish I’d come before I needed proof.’

‘You would have come anyway,’ Tom said.

‘But you didn’t need a push.’

‘Try living in a company shack in a coal town,’ Tom said. ‘Try busting your ass in the dust bowl of Oklahoma.’

He sensed that what he had said was grotesquely wrong but he couldn’t fathom why. Surely it was feasible to compare injustices in the United States with those of Spain. I knew a great injustice was being perpetrated. Those were Adam Fleming’s very words.

But such is the spontaneity of relationships such as this that anticipation is everything. No need to tell a joke: just point the way. No need to say goodbye: there is farewell in your greeting.

And now Tom Canfield knew.

He said, ‘Your sister, where was her husband killed?’

‘In Madrid,’ said Adam who, of course, knew by now.

‘But you’re holding a Russian rifle.’

‘And you’re wearing a German flying jacket.’

‘I took my rifle from the body of a dead Republican.’

‘I bought my flying jacket in a discount store in New York.’

Delgado said from the lip of the shell-hole, ‘I am delighted to see, Fleming, that you have taken a prisoner.’

CHAPTER 5

Able Seaman Thomas Emlyn Jones, RN, was a man of many talents. He could sing like a chorister, pluck pennies from the ears of children visiting his ship, arm-wrestle a dockside bruiser into submission, summon delicate fevers when threatened with onerous duties and tune the Welsh lilt in his voice on to a wavelength that could cajole girls from Portsmouth to Perth into committing perilous indiscretions.

But midwifery was not one of his accomplishments. When Martine Ruiz emerged from a cabin on HMS Esk, swathed in a sheet, hand supporting her considerable belly, and said, ‘Please help me, I’m having a baby,’ he was unnerved.

He had watched her board the destroyer with the other refugees at the palm-fringed port of Alicante at dusk and she had reminded him of a galleon in full sail, so stately in her bearing that nothing untoward could possibly happen in the immediate future. Now here she was, alarm bells sounding.

His first instinct was to run on his bandy miner’s legs to the sickbay to get help but the Esk had paused north of Alicante to pick up wounded refugees from a moonlit beach, and the ship’s surgeon and his assistants were busily and bloodily engaged. In any case the woman wouldn’t let go of him.

Pulling him into the cabin, she lay on the bunk and said, ‘It is happening,’ as indeed it seemed to be, belly convulsing, body heaving, hands white-knuckled.

Hot water and towels: those, Taffy Jones remembered, were the essentials. He had observed them being taken into the bedroom in the dark and crouching cottage in the Rhondda Valley when his exhausted mother was giving birth to one of his sisters; he had heard the doctor calling for them in the sort of movie where the heroine collapses in a snowstorm and gives birth to twins.

The woman on the bunk screamed.

He turned on the hot water in the wash-basin and grabbed the towels from the rack.

‘There, there, lovey,’ he said, ‘everything will be all right, just you see.’ He held her hand and she gripped it with a fearful strength.

What now? ‘Push,’ he said as the midwife, who smelled of gin, had said to his mother. ‘Push, that’s it, lovey, you just help her on her way,’ because he had no doubt in his mind that a lady was about to be added to the passenger list.

He bathed her sweating face with a towel, not too hot, and laid another across her labouring belly. Observing her agony, hearing her cry, he determined that in future he would be more considerate towards women. No more buns in the oven for Taffy Jones.

The sheet slipped away and a head emerged from between her wide-flung thighs. ‘Push,’ he said gently, ‘push,’ although whether he was addressing mother or child he couldn’t say. What did you do when the baby finally made it? All you heard in the movies was a plaintive squawk from behind closed doors.

‘There, there, lovey, she’s on her way.’

The fingers of Martine Ruiz gripped his hand like talons. She said, ‘You will have to help.’

He stared at the baby; it seemed to have given up the struggle. Perhaps it didn’t like what it saw. He placed two paws round the tiny shoulders and pulled very gently; when he got back to Cardiff he would marry the girl who worked in the newsagents and they would take out a mortgage on a £600 semi and have two kids.

The baby, creased and slippery with mucus and blood, swam forward. Taffy Jones, aware of unplumbed emotions stirring within him, sighed. ‘She’s almost there,’ he said softly. ‘Almost there.’

‘In my bag,’ Martine Ruiz whispered in her accented English that he found difficult to understand. ‘A pair of … scissors.’

He opened her expensive-looking handbag and took them out. The cord had to be cut and knotted; that was it. The prospect didn’t alarm him: authority had settled comfortably upon him.

He dipped the blades of the scissors into the hot water, snipped the cord with one deft cut and tied it. Then he examined the baby.

‘It’s a girl,’ he told Martine Ruiz.

But it was making no sound. Was it breathing? He picked it up in his big hands and anxiously held it aloft. A smack followed by a squawk, he remembered.

‘Come on, you little bugger,’ Taffy Jones pleaded.

Still holding the baby in one paw, he ran the fingers of the other down its flimsy ribs.

And the baby laughed. Taffy Jones swore to it then and many times later in dockside bars where normally midwifery doesn’t rate high in conversational priorities. Some might have mistaken that first utterance for a whimper but Taffy knew better. He was there, wasn’t he? ‘Made a contribution to medical science, perhaps. To mankind, maybe,’ and, if it was his round, his drinking friends would nod sagely.

At the time Taffy Jones merely smiled at the baby who was now making noise that could, perhaps, be mistaken for crying and cooed, ‘Oh, you little bugger you.’

He gently washed the baby and handed it to its mother.

Ana Gomez worried. Not at this moment about her husband who was fighting at Jarama but about the future he was fighting for.

In the Plaza de España in Madrid, close to the front line, she watched Pablo kicking a scuffed football near the waterless fountains and Rosana making a sketch of the statue of Don Quixote.

Pablo intended one day to play for Real Madrid; Rosana to have her pictures hung in the Prado. Or would he, perhaps, play for Moscow Dynamo while Rosana exhibited in the Pushkin Museum?

This was what worried Ana as she paused in the hesitant sunshine on her way to hear her cousin Diego, an orator if ever there was one, speak in a bombed-out church off the Gran Via.

At first the different factions within the crusade hadn’t bothered her. They were all fighting for the same cause, weren’t they, so what did it matter if you were FAI or CNT or UGT or a regional separatist? She herself had favoured Anarchism because the belief that ‘Every man should be his own government, his own law, his own church’ seemed to be the purest form of revolution.

But what she believed in even more passionately was Spain – a wide, free country where equality settled evenly with the dust in the plains and the snow in the mountains – and she now believed that this vision was endangered. By the Russians. True, they were providing planes and tanks and guns but do we have to pay with our pride? Everywhere the Communists seemed to be taking over – there was Stalin smiling at her benignly from a banner on the other side of the square. And in Barcelona, so she had heard, the Communists who took their orders from the Kremlin were poised to crush the Communists in POUM who were independent of the Kremlin.

What has it come to, Ana Gomez asked herself, when not only are we divided but the divisions themselves are split? Where was the single blade of revolution that had flashed so brightly at the beginning?

A breeze rippled the banner of Stalin making a deceit of his smile.

Ana called the children. Outside the Gran Via cinema she met Carmen Torres who was taking the children to see the Marx Brothers. She gave them five pesetas and, skirting a bomb crater, made her way through the debris and broken glass to the church.

It was open to the sky and naked and, when she arrived, Diego was about to speak from the stone pulpit. Watching him from the back of the nave, Ana felt uneasy. Although she despised the priests who had defiled religion she still believed in the God they had betrayed and she didn’t like to hear politics instead of prayers in his house. But there was more to her unease than that: there was slyness abroad in the roofless church, a sulking defiance, and at the sides of the congregation stood several men with zealots’ faces.

Diego offered his congregation the clenched fist salute. ‘No pasarán!’ he shouted and they hurled it back at him. He spread his arms. We are one, his arms said. Then, with a plea and sally, he beckoned them into his embrace and when they were there he told them what they had to do.

Diego, with his myopic eyes peering from smoked glasses and his small, button-bursting stomach, did not have a prepossessing appearance, and this was perhaps the secret of his oratory: no one could believe that such fire could issue from such a nondescript body.

But on this disturbing day even Diego sounded suspect to Ana. First came the impassioned affirmation that they would stand together to fight the Fascist oppressors who had ‘plundered their souls’ – lively enough, but predictable, as were the warnings of sacrifices to be endured and the promises of the individual freedoms to be celebrated after the bourgeoisie were sent packing.

After that Diego, man of the people, faltered. And whereas normally his voice soared, hoisting collective passions with it, before diving as abruptly as an eagle on its prey, it was flat and cautious.

Ana listened. State controls, centralism … workers to have their say, of course … but while the war lasted the country must be protected against lawlessness … What was this?

On the sidelines the men with the zealots’ faces clapped. The rest of the audience followed suit but the customary cheers remained stuck in their throats. Diego moved on to ‘our good friends the Russians’.

Planes glinted silver in the sky above the nave. The earth shook with the impact of their bombs. Anti-aircraft guns started up.

‘We must never forget that the Soviet Union fought a civil war against capitalist exploitation …’

And look where it got them. Diego, why are you reciting to us?

‘No pasarán!’ she shouted and strode down the aisle towards the altar, arm raised, fist clenched. ‘No pasarán!’ Ana Gomez, is this you?

Two of the men from the sidelines stood in her way. They smiled indulgently but they were snake-eyed and muscle-jawed, these men.

‘Please return to your place, Ana Gomez.’

How did they know her name?

She half-turned to the audience.

‘This is a woman’s war as well, comrades, in case you hadn’t heard. Ask La Pasionaria.’

From the body of the crowd came a man’s voice: ‘Let her speak. Where would we be without our women?’

‘Thank you, comrade,’ Ana shouted. Two years ago he would have told her to get back to the kitchen!

One of the sidesmen said, ‘The meeting is over. I order you all to disperse in an orderly fashion.’

Order! That was his mistake.

‘Let her speak … Go back to Moscow … This is our war …’ The audience began to stamp and slow-handclap.

The sidesman’s hand went to the long-barrelled pistol in his belt.

‘Go ahead, shoot me,’ Ana said.

The shouts seemed to unify into an ugly sound that reminded her of the first warning growl of a dog with bared teeth.

The sidesmen looked at each other, and shrugged.

Diego came down from the pulpit and took her arm. ‘What are you trying to do to me?’ He had taken off his spectacles; he was naked without them. ‘Didn’t you get my message?’

‘Message? I received no message.’

‘What are you going to do?’

‘Speak to them,’ Ana said pointing at the audience which was quiet now. ‘The way you used to.’

She pushed past him and mounted the steps of the pulpit. She saw beneath her, as priests before her had seen, faces waiting for hope. What are you doing here, Ana Gomez, mother of two, wife of a museum guard, resident of one of the poorest barrios in Madrid? Who are you to talk about hope?

She laid both hands on the cold knuckle of the pulpit. She had no idea what she was going to say, no idea if any words would emerge from her lips. She noticed the scowling faces of the two men who had tried to stop her. She heard herself speaking.

‘My husband is fighting at Jarama.’

A hush as silent as night settled on the people below her. She saw their poor clothes and their hungry faces and she felt their need for comfort.

‘He did not want to fight.’ She paused. ‘None of us wanted to fight.’

Gunfire sounded distantly.

‘All we wanted was enough money to live decently – decently, comrades, not grandly. All we wanted was a decent education for our children.’

A child whimpered in the congregation.

The two sidesmen seemed to relax; one leaned against a pillar.

‘All we wanted was a share of this country. Not a grand estate, just a decent plot that belonged to us and not to those who paid us a duro for the honour of tilling their land.’

Sunlight shining through the remnants of a stained-glass window cast trembling pools of colour on the upturned faces.

‘All we wanted in this city was a decent wage so that we could feed our families and give them homes and live almost as grandly as the priests.’

She stared at the sky which the bombers had vacated and whispered, ‘Forgive me God.’ But although she knew not where the words came from, they could not be stemmed.

‘No, we did not want to fight: they made us, the enemy who sought to deny us our birthright. But now, at their behest, we shall win and Spain will be shared among us.’

They clapped, and then they cheered, and hope illumined their faces. The two sidesmen clapped and exchanged glances that said they need not have worried. Ana paused professionally, then held up her hands, palms flattened against her audience.

‘I repeat, Spain will be shared among us. Not among foreigners.’ A shuffling silence. The two men snapped upright and stared at her. ‘We shall always be grateful for the help that has been given to us – without that we might have perished – but let us never forget that the capital of Spain is Madrid, not Moscow.’

The audience applauded but now they were more restrained. The sidesmen walked briskly out of the church.

In a bar near the church, where brandy was still available to distinguished revolutionaries, Diego said, ‘Why did you do that to me?’

‘Do what?’

‘Attack the Communists.’

‘Because I am an Anarchist like you.’

‘But I’m not: I’m a Communist.’

Diego leaned forward on his stool and stared despairingly into his coffee laced with Cognac.

Ana folded her arms. ‘You are what?’

‘A Communist. They have even promised me a party card. That was a Communist meeting; I sent Ramón to tell you.’

‘Ramón? Who is this Ramón?’

‘My assistant. But he probably got drunk on his way.’ He stroked his damp moustache with one nail-bitten finger. ‘You were making an anti-Communist speech at a Communist meeting. Mi madre!’ He smiled grimly.

‘I was making a pro-Spanish speech.’

‘The capital of Spain is Madrid, not Moscow … Yes, very patriotic, cousin. I congratulate you on condemning us to the firing squad.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ Ana gulped her coffee. ‘How could any true Spaniard disagree?’

‘It wasn’t exactly diplomatic. Not when Moscow is supplying us with our arms.’

‘We are paying for them in gold.’

‘They have our gold: we still need their arms.’

‘And so now we should give them our souls? Do you want Spain to become a colony of the Soviet Union?’

‘Keep your voice down; you aren’t in the pulpit now.’ Diego took off his glasses and glanced around as though he could see better without them. ‘We need them,’ he said. ‘Without them we are doomed.’

Ana said softly, ‘Why did you sell your soul, Diego?’

‘Because I believe that salvation lies with the Communists.’

‘What about those dreams of Anarchism you once cherished? “There is only one authority and that is in the individual.” Who said that, Diego?’

‘Me?’

‘You. What did they buy you with, Diego?’

‘We are all fighting for the same cause.’

‘That wasn’t what I asked.’

‘I have been promised a high office in the administration when the war is over.’

‘And a grand house and a decent salary?’

‘Commensurate with my office,’ Diego said.

‘Perhaps,’ Ana said, ‘they will pay you in roubles.’

‘I tell you, we are all fighting for the same cause.’

It was then that Ana realized that one contestant had been missing from the conversation – the enemy, the Fascists.

Has it come to this? she asked herself. She strode out of the bar and down the street to the cinema where her children were watching the Marx Brothers.

On the Jarama front the fighting had stopped for the night. The combatants had retired to debate how best to kill each other in the morning and, except for the intermittent explosions of shells fired to keep the enemy awake, the battlefield was quiet.

In a concrete bunker captured from the Republicans Colonel Carlos Delgado considered the two foreigners interfering in his war. A picture of Franco hung from the wall recently vacated by Stalin; a map of the Jarama valley and its environs, crayoned with blue and red arrows, was spread across the desk.

Delgado’s fingers searched his freshly-shaven cheeks for any errant bristles, tidied the greying hair above his ears where his cap had rested. His khaki-green tunic was freshly pressed and his belt shone warmly like dark amber. His voice, like Franco’s, was high-pitched.