The Kitchen Diaries II

curly kale: 250g

soft cooking chorizo: 250g

skinned whole almonds: 50g

a little groundnut or sunflower oil

a clove of garlic, peeled and crushed

Wash the kale thoroughly – the leaves can hold grit in their curls. Put several of the leaves on top of one another and shred them coarsely, discarding the really thick ends of the stalks as you go.

Cut the chorizo into thick slices. Warm a non-stick frying pan over a moderate heat, add the slices of chorizo and fry until golden. Lift them out with a draining spoon on to a dish lined with kitchen paper. Discard most of the oil that has come out of the chorizo (better still, keep it for frying potatoes) and wipe the pan clean. Add the almonds and cook for two or three minutes, till pale gold, then lift out and add to the chorizo.

Warm a little oil in the pan, add the crushed garlic and shredded greens and cook for a couple of minutes, turning the greens over as they cook, till glossy and starting to darken in colour. Return the chorizo and almonds to the pan, add a little salt and continue cooking till all is sizzling, then tip on to hot plates.

Enough for 2 as a light main course, 4 as a side dish

FEBRUARY 20

The pancetta question

Modern cookbooks, mine included, are awash with pancetta – to start a sauce, flavour a soup, add protein to a leaf salad or simply give depth and savour. But could we not use bacon?

Though both bring a similar note to a recipe, pancetta has a few advantages over bacon. Most bacon in the UK is sold in rashers, while pancetta is more often found in useful cubes (often labelled as cubetti), which give more body to a sauce than strips of wafer-thin bacon. Most cures are less salty than our own back or streaky, and seem to have a faintly herbal note to them. (In practice they don’t, but most pancetta is more subtly aromatic.)

It is this subtlety that makes pancetta more suitable for so many recipes. It tends to become part of the backbone of a dish, rather than intrude as bacon can occasionally do. But that is not all. The reason it is so often specified over bacon is that it is a more consistent product. Suggest chopped bacon for a recipe and you can get any one of a hundred different cures, ranging from pale and watery to deeply smoky and dry. Although there are most certainly differing qualities of pancetta available, it is by and large consistent and therefore a safer bet.

A block of pancetta bought from an Italian deli will keep in decent condition in the fridge for a week. Bacon rashers less so. I regard a lump of the stuff, dirty rose pink in colour, thickly ribbed with white fat, as one of the kitchen essentials – like lemons, Parmesan and olive oil. A meal it does not make, but the difference it adds to even a few lettuce leaves or a bowl of soup is extraordinary. Today’s bean and spaghetti soup is a case in point.

Pancetta and bean soup with spaghetti

The one good thing about having little in the larder is that it prompts experimentation.

pancetta in the piece: 175g (you can use pancetta cubetti at a push)

a little olive oil

garlic: 2 small cloves

chopped tomatoes: two 400g cans

chickpeas or other large, firm pulses: a 400g can, drained

spaghetti: 250g

parsley: a small bunch

extra virgin olive oil

Chop the pancetta into small pieces, then fry for a minute or two in the olive oil over a moderate heat. Once the pancetta starts to turn golden, peel and crush the garlic and add to the pan, followed by the chopped tomatoes, 400ml water and the drained canned chickpeas or beans. Bring to the boil and season with salt and black pepper. Lower the heat so that the mixture simmers gently, thickening slowly, for about fifteen to twenty minutes.

Break the spaghetti into short lengths and boil in deep, generously salted water for eight or nine minutes, till tender, then drain. Roughly chop the parsley and stir into the soup together with the spaghetti. I add a trickle of really good olive oil to each bowl at the table.

Enough for 4

FEBRUARY 21

A family cake

Don’t you just hate lining cake tins? I know you don’t have to any more with the ready-made paper liners available from cookware shops, but they have the habit of making everything come out looking like a shop-bought cake.

The truth is that cakes rarely stick round the sides, and if they do they can be loosened with a palette knife (run the knife smoothly around the edge, pressing firmly against the side of the tin, without digging into the cake). I now line only the base, cutting a simple disc of brown baking parchment or grease-proof paper to fit the base of the tin. It takes thirty seconds, stops the cake attaching itself to the base and leaves your handiwork looking homemade.

An apricot crumble cake

This is the grown-up version of the little cakes I made a week or so ago (see here). A family cake, suitable for tea or dessert, in which case it will benefit from an egg-shaped scoop of crème fraîche.

dried apricots: 250g

softened butter: 175g

golden caster sugar: 175g

eggs: 2

ground almonds: 80g

self-raising flour: 175g

ground cinnamon: a pinch

vanilla extract: a few drops

For the crumble:

plain flour: 100g

butter: 75g

demerara sugar: 2 tablespoons

jumbo oats: 3 tablespoons

flaked almonds: 2 tablespoons

a little cinnamon and extra demerara sugar for the crust, and perhaps a little icing sugar to finish

Preheat the oven to 160°C/Gas 3. Line the base of a 22cm round cake tin with baking parchment.

Put the apricots in a saucepan, cover with water and bring to the boil. Turn down the heat and simmer for twenty minutes, then turn off the heat and leave them to cool a little.

Beat the butter and sugar in a food mixer for five to ten minutes, till light and pale-coffee coloured. Break the eggs, beat them gently just to mix the yolks and whites, then add them gradually to the mixture with the beater on slow. Fold in the ground almonds, flour and cinnamon, then add the vanilla extract. Scrape the mixture into the tin and smooth the surface.

Drain the apricots and add them to the top of the cake mixture. Make the crumble topping: blitz the flour and butter to crumbs in a food processor, then add the demerara sugar, oats and flaked almonds and mix lightly. Remove the food processor bowl from the stand and add a few drops of water. Shake the bowl a little – or run a fork through the mixture – so that some of the crumbs stick together like small pebbles. This will give a more interesting mix of textures. Scatter this loosely over the cake, followed by a pinch of cinnamon and a little more demerara. Bake for about an hour, checking for doneness with a skewer; it should come out clean.

Remove the cake from the oven and set aside. Dust with a little icing sugar if you wish and slice as required. The cake will keep well for three or four days.

Enough for 8

FEBRUARY 23

Desperate for dessert

There are apples that fluff up when they are cooked and apples that keep their shape. But you know that, if you have read the apple chapter in Tender Volume II, or indeed have ever made apple sauce or baked an open apple tart.

What I find particularly useful are recipes that work with ‘fruit bowl’ apples, the sort you tend to have knocking around. This is such a recipe. It’s a pudding for when you didn’t intend to have a pudding, until someone asked for one.

Fried apples with brown sugar and crème fraîche

The apples should be cooked over a fairly low heat so they soften but don’t colour too much before you add the sugar. Once the sugar is added, things happen quite quickly, so don’t be tempted to take your eye off the pan. The Calvados is a suggestion. You can add a straightforward cognac if you prefer, or leave it out altogether. If there is no crème fraîche around, use ordinary double cream – though the result will be a little sweeter.

a large apple

a little lemon juice

light muscovado sugar: 2 tablespoons

butter: 50g

Calvados: 1 tablespoon

crème fraîche: 2–3 tablespoons

Cut the apple into quarters and remove and discard the core and pips. I don’t peel my apples for this recipe, but it is up to you. Cut the apple into thick slices, put them in a basin and squeeze over a little lemon juice, just enough to stop them browning.

Melt the butter in a shallow, non-stick pan. Add the apple slices and let them cook over a moderate heat for about ten minutes, turning them as necessary and lowering the heat if they colour too quickly. When they are soft and golden, scatter over the sugar and let it melt in the butter. As it starts to turn to caramel in the pan, add the Calvados and crème fraîche. Once the cream has melted around the apple, serve immediately.

Enough for 2

Pumpkin, tomato and cannellini soup

This is quite a substantial soup and could easily double as a main dish. To make a quick version, use canned beans. Drain them of their canning liquid and rinse them thoroughly, then add them to the soup once the tomatoes have simmered down to a slush. You could use any bean, but the cannellini type has a good contrast of texture to the soft vegetables and tends to stay quite firm during cooking. The soup can be kept in the fridge for several days.

dried cannellini beans: 250g

onions: 2

olive or rapeseed oil: 2 tablespoons

garlic: 2 or 3 cloves

rosemary: a small sprig

tomatoes: 400g

pumpkin: 800g (about 650g prepared weight), peeled and cut into chunks

parsley: a small bunch

a little extra virgin olive oil

Soak the dried beans in cold water overnight. Drain and rinse, then tip into a large, deep pan and cover them with water. Bring to the boil, partially cover with a lid, then turn down the heat so they cook at an enthusiastic simmer. Don’t be tempted to add any salt at this point, as it will toughen the beans. Skim off any froth that rises to the surface as they cook, and occasionally check the water level and top up from the kettle if necessary. Test for doneness after forty-five minutes or so; they should be tender but not soft. Drain and set aside.

Peel and roughly chop the onions. Warm the oil in a deep pan, add the onions and cook for about ten minutes, until soft. While the onions cook, peel and slice the garlic and add to the pan, together with the rosemary needles, roughly chopped. Cut the tomatoes in half and stir them into the onions. Continue cooking for five minutes, then pour in 750ml water and bring to the boil. Add the pumpkin pieces to the pan, season with salt and black pepper and leave to simmer gently for thirty to forty minutes, until the pumpkin is tender to the point of a knife.

Tip the drained beans into the pan and continue cooking for ten minutes. (If you want to cool everything at this stage and put the soup in the fridge overnight, it will be all the better for it.) Remove the leaves from the parsley and chop roughly, then stir them into the soup. Ladle into deep bowls, trickle a little extra virgin olive oil over the top and serve.

Enough for 4

FEBRUARY 24

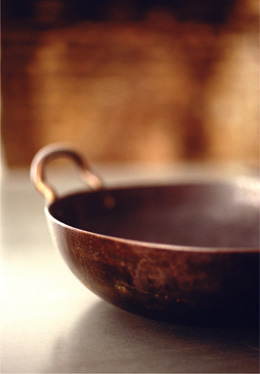

The old wok

I have three woks. The oldest is cheap, thin, and has been a friend for longer than I can remember. A purchase from Chinatown, now blackened from years of use and, if I am honest, a little rusty here and there. Its diameter is 40cm, which will make a stir-fry (mushroom and broccoli, prawn and fat, fresh noodles, chicken and choy sum) for two.

The trendy thick woks with famous names are rubbish. Leave them in the shops. Never pay more than a few quid for a wok. Go for one made from steel no thicker than a ten-pence piece. It will take more looking after (it needs seasoning to stop it rusting) but it will reward you with a better stir-fry. The whole point of a stir-fry is the speed at which the meat cooks. A slow stir-fry where the pan is too thick or the heat too low simply isn’t a stir-fry. It’s a stew-fry.

Woks will eventually season themselves. They will develop a surface patina of burned-on oil that will be both non-stick and non-rust. I speed the matter up by putting a new wok, coated in groundnut oil, into a hot oven and leaving it for an hour or so for the oil to burn on. I then wipe the surface with kitchen paper without washing it and let the wok cool. I sometimes do this several times, depending on the progress. If the wok has a wooden handle, then it’s a case of doing it on the hob. A smoky business.

Oyster sauce, in particular the Lee Kum Kee brand, is one of the sauces that are always present in my fridge. Dark, velvety and not as fishy as it sounds, it keeps in good condition for a few weeks. Its destination is usually a last minute stir-fry – tonight, one of cubes of pork, too much garlic and some mushrooms. As a simple supper, it is difficult to beat.

Pork with garlic and oyster sauce

Plus greens somewhere.

flavourless oil: 5 tablespoons at least

cubed pork shoulder or fillet: 350g

garlic: 3–4 cloves

shallots: 2

small, hot red chillies: 4

mushrooms, shiitake, chestnut, whatever: 150g

oyster sauce: 3 heaped tablespoons

Shaoxing wine: 3 tablespoons

Heat the wok. Add 2 tablespoons of oil. When it starts to smoke, add half the meat and let it colour, removing it as it turns golden at the edges. Repeat with the second batch of meat, using a little fresh oil if you have to.

Meanwhile, peel and finely chop the garlic and peel and slice the shallots. Finely chop, but do not seed, two of the chillies. Leave a couple whole to add a deeper, subtler flavour. Get the wok hot, pour in the remaining oil and let it start to smoke, then add the chopped garlic, shallots and chillies, stirring as they cook. Fry them for a minute or two till they start to colour. Add the mushrooms, whole or torn up if they are large. Continue stir-frying till they are soft and lightly coloured, then return the meat to the pan. Once the meat is thoroughly hot, stir in the oyster sauce and the wine and bring to the boil. Let the resulting sauce reduce for a minute, maybe two, then serve.

Enough for 2

FEBRUARY 25

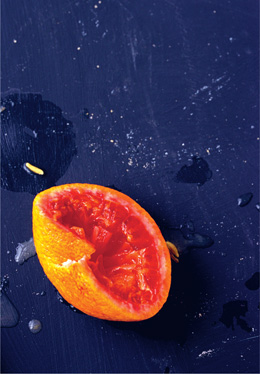

In the squeezing of a lemon

A warm lemon will yield more juice than a cold one. So it is better to keep them at room temperature than in the fridge. More importantly, a ripe or even slightly overripe fruit will give up more juice than one so hard you can barely squeeze it. Many lemons are sold unripe. A ripe lemon is often a deeper yellow, and yields gently under pressure. I roll my lemons on the work surface before juicing them, pushing firmly down on them with the palm of my hand. I seem to get even more juice that way.

The standard domestic glass lemon squeezer, the one with a moat to catch the juice and tiny beads to hold back the pips, works well enough. The deeper, stainless steel versions are good too, letting the juice fall through into the base. Yet I get the best results with a wooden lemon reamer. The simplicity appeals, a pointed ridged cone with a beech or olive wood handle, and the fact that it has been made by hand rather than machine. Some are made from one piece of wood rather than two (the handle is often made separately from the ridged cone). But what sets it apart from the others is its simplicity and, in some cases, its beauty. Of course, the pips escape into the juice. You simply fish them out with your fingers.

Lemon tart

The tart case needs to be made with care, so the edges don’t shrink as they cook, otherwise it will leak once the filling goes in. I keep a little bit of pastry aside for patching, so that if any cracks or gaps appear I can patch them before I add the lemon custard.

For the pastry:

plain flour: 180g

butter: 90g

caster sugar: a tablespoon

a large egg yolk

a little water

For the filling:

eggs: 4, plus 1 extra egg yolk

caster sugar: 250g

zest of 2 unwaxed lemons

zest and juice of a small blood orange

lemon juice: 160ml

double cream: 180ml

Make the pastry: put the flour into a food processor, add the butter, cut into pieces, and blitz to fine breadcrumbs. If you prefer, rub the butter into the flour with your fingertips. Add the sugar and egg yolk and just enough water to bring the mixture to a firm dough, either in the machine or by hand. The less water you add, the better – too much will cause your pastry case to shrink as it bakes.

Tip the dough on to a floured board, pat it into a round, then roll it out a little larger than a 24cm loose-bottomed tart tin. Lift the pastry carefully into the tin, pushing it well into the corners and making certain there are no holes or tears. Trim away any overhanging pastry, then place in the fridge for twenty minutes.

Set the oven at 200°C/Gas 6. Put a baking sheet in the oven to heat up. Line the pastry case with foil, fill with baking beans and slide it on to the hot baking sheet. Bake for twenty minutes, then remove from the oven and carefully lift out the beans and foil. Return the pastry case to the oven for five minutes or so, until the surface is dry to the touch. Remove from the oven and set aside. Turn the oven down to 160°C/Gas 3.

Make the filling: break the eggs into a bowl and add the egg yolk and caster sugar. Grate the lemon and orange zest into the eggs. Pour in the orange and lemon juice. Whisk, by hand, until the ingredients are thoroughly mixed, then stir in the cream.

Pour the mixture into the baked tart shell and slide carefully into the oven. Bake for thirty-five to forty-five minutes till the filling is lightly set. Ideally, the centre will still quiver when the tray is shaken gently.

Enough for 8

FEBRUARY 26

A little meal of peace

Sometimes, I rather like noise. The testosterone-fuelled roar of a football match heard from my back garden; the tired and blissfully happy sounds of a crowd singing along at a festival; the swoosh of a barista’s steam wand. But most times I prefer peace and quiet. The sound of snow falling in a forest is more my style – something I have yet to hear this year.

There is quiet food, too. The tastes of peace and quiet, of gentleness and calm. The solitary observance of a bowl of white rice; the peacefulness of a dish of pearl barley; running your fingers through couscous. The thing these have in common is that they are grains or something of that ilk. What is it about these ingredients that makes them so calming? Could it just be that they bring us gastronomically down to earth, show us how pure and simple good eating can be? This is food pretty much stripped of its trappings. It is, after all, the food that many people survive upon.

The peacefulness of grains, their earth tones and the fact that they don’t snap or crunch between the teeth, is what makes them food to eat when we are looking for solace and calm. The fact they are not from a dead animal probably has something to do with it, too.

More and more, I make a main course of what is generally thought of as an accompaniment. Tonight, I make a dish of pale bulgur wheat, cooked with chopped onions, bacon, mushrooms and dill. It is a bit of a hybrid (pork and bulgur are not often found sharing a plate) but it turns out to be one of those ridiculously cheap meals that hits all the right notes.

Bulgur and bacon

I sometimes spoon a little seasoned yogurt – salt, pepper, paprika – over this at the table, stirring it into the grains. But mostly I leave the pilaf as it is, enjoying the warm, homely grains and juicy nuggets of mushroom as they are.

smoked streaky bacon: 200g

onions: 2

olive oil

garlic: 2 cloves

small mushrooms: 250g

bulgur wheat, medium fine: 250g

boiling water from the kettle: 400ml

sprigs of parsley: 3–4

dill: 6 sprigs

butter: 60g

Cut the bacon rashers into short, thick pieces. Peel the onions and slice them thinly. Warm a couple of tablespoons of olive oil in a large, shallow pan over a low heat, add the sliced bacon and stir occasionally till the fat has turned pale gold. Peel and finely chop the garlic. Add the onions and garlic to the pan and leave till soft, golden and translucent, stirring from time to time.

Quarter the mushrooms and add them to the softening onions. Leave them to cook for five minutes or so, with the occasional stir. Add the bulgur with a pinch of salt, then pour in the boiling water. Cover tightly, switch off the heat and leave for fifteen minutes.

Roughly chop the parsley leaves and dill. Lift the lid from the pan and add the butter, herbs and a little salt and pepper. Stir till the grains are glossy with butter, then serve.

Enough for 4

FEBRUARY 27

Coconut cream

One of the reasons I have stayed put for more than a decade is because of the way this house floods with light in the mornings. Softened by closed blinds, the sun that comes in from the east wakes you gently, if a little earlier than you would like. This morning, the rooms fill with honeyed light, like a Hammershoi painting. I suddenly realise how much I have missed it these last few weeks.

Sunlight, even on a relatively cold day, has a habit of changing my appetite. Pasta, potatoes and grains feel inappropriate and heavy. The brown food that has provided such homely comfort on the grey days since the year’s start suddenly looks out of place.

Coconut is one of those ingredients that tend to walk hand in hand with sunshine. It smacks, albeit softly, of trips to Kerala and Thailand, of tiny scented pancakes for breakfast on sun-filled terraces, of lime juice and chillies and, of course, sun-tan oil. All of which is about as far as you can get from a February day within a ball’s throw of Arsenal Stadium.

I met coconut first in the form of a neat, sweet Bounty bar, and as a coating, along with raspberry jam, for the tiny, castle-shaped sponges we wrongly called madeleines. Later, it became the principal seasoning of a holiday in Goa and then, a decade on, of the deep, pale-green soups of Thailand. For an ingredient of which I am not particularly fond, the flesh of the coconut is laden with happy memories.