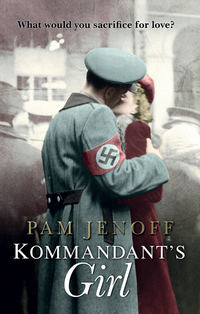

Kommandant's Girl

Finally, around two o’clock in the morning, we settled in the kitchen with mugs of strong coffee. I hesitated for several minutes before speaking. There was so much I wanted to ask Krysia that I didn’t know where to begin. “How did you …?” I began at last.

“Become involved with the resistance?” She stirred her coffee once more, then placed the spoon in the cradle of the saucer. “I always knew about Jacob’s causes. He spoke to me about it because his mother was not that interested, and his father worried too much for his safety. I was concerned, too, of course,” she added, taking a sip from her cup. “But I knew he was unstoppable.” So did I, I thought. “He came here late one night shortly after the occupation,” she continued. I realized she must have been talking about the night before his disappearance, when Jacob had not returned home for many hours. “He didn’t exactly tell me what was going on, but he asked me to keep an eye on you, in case anything should happen to him. I asked what else I could do, and we realized together that my home and my position might be useful somehow. He put me in contact with people … the specifics did not come until after he was gone.”

“But this is terribly dangerous for you! Aren’t you at all afraid?”

“Of course I am, darling.” The corners of her mouth pressed wryly upward. “Even an old widow with no children wishes to live. But this war …” Her expression turned serious. “This war is the shame of my people. Having you and the child live here with me is the least I can do.”

“The Poles didn’t start this war,” I protested.

“No, but …” Her thought was interrupted by a light scratching sound at the back door. “Wait here.”

Krysia tiptoed downstairs. I heard whispers, some movement, then a tiny click as the door shut. Krysia came back up the stairs, her footsteps slower and heavier now. When she reached the landing, her arms overflowed with a large cloth bundle. I stood to help her and together we carried the sleeping child to the third floor.

We set the child on the crib and Krysia unwrapped the blankets in which he had been swaddled. At the sight of the child’s face, I gasped loudly. It was the blond child whose mother had been shot in the alleyway.

“What is it?” But before I could answer, the child, awakened by my gasp and Krysia’s voice, began to whimper. “Shh,” she soothed, rubbing the child’s back. He settled into sleep once more.

Silently, we backed out of the room. “That child,” I whispered. “That’s …”

“The descendant of Rabbi Izakowicz, the great rabbi of Lublin. His mother was shot …”

“I know! I saw it happen from our apartment.”

“Oh, you poor dear,” Krysia said, patting my shoulder.

“You said he has no parents. What about his father?”

“We don’t know. He was either shot in the woods near Chernichow or taken to a camp. Either way, it doesn’t look good.”

I squeezed my eyes tight then, remembering the scene in the alleyway. Surely they wouldn’t kill the rabbi, I had said to my parents that night. “She was with child when she was killed,” I added, my eyes beginning to burn. “His mother, I mean.”

Krysia nodded. “I had heard that. It makes what we are doing that much more important. The child is the last of a great rabbinic dynasty. He must be kept alive.”

Krysia and I took turns sleeping that night in case the child should awaken and be confused or upset by the strange surroundings, but he slept through the night and did not stir. The next morning, I went to his crib and lifted him, still in his street clothes. He was damp with sweat, his blond curls darkened and pressed against his forehead. He blinked but did not make a sound as I placed him on my hip. Instead, he wrapped his hands around my neck and rested his head on my shoulder as though he had done this every day of his young life. Together we headed down the stairs to the kitchen, where Krysia was once again preparing breakfast. At the sight of us in the doorway, her eyes warmed and her face broke into a wide smile.

A week later, Lukasz and I would walk into town for our debut appearance as gentiles at market. His eyes would light up at the sight of an ice-cream cart and I, unable to resist, would take a few pennies from our food money to buy him a vanilla cone. And this is how Lukasz, the son of the great rabbi of Lublin, and Emma, the daughter of a poor Kazimierz baker, came to live with the elegant Krysia Smok in a cottage that seemed like a palace in Chelmska.

CHAPTER 6

“We will be having a dinner party on Saturday,” Krysia announces as routinely as though she is discussing the weather. The damp white towel I am holding falls from my hands to the dirt.

We are working in the garden, Krysia pulling weeds from around the spry green plants that are just beginning to bud, me hanging the linens we washed in a large basin an hour earlier. A few feet away, Lukasz digs silently in the dirt with a stick. It has been more than a month since Lukasz and I came to live with Krysia. I can tell that she is overwhelmed at times. Since arriving here, I have tried to take on as much of the housework as I can, but the labor has still taken its toll on her. Her delicate hands seem to grow more callused by the day, and her work dresses have become soiled and tattered. Yet despite her sacrifices, Krysia seems to like having us around. We are the first real companions she’s had since Marcin died. She and I make easy company for each other, sometimes chatting as we work around the house, other times falling into deep silence. There is, after all, much to think about for both of us. I know she worries, as I do, about Jacob, and about us, how we must never be discovered, what would happen if we were.

The child’s presence, however, keeps us from wallowing too deeply. Lukasz is a beautiful boy, calm and undemanding. In the weeks he has been with us, though, he has not spoken a word. We try desperately to make him laugh. Sometimes I invent childish games, and often in the evenings, Krysia plays lively tunes on the piano as I whirl him around in my arms to the music. But so far it has not helped. Lukasz watches patiently, as though the revelry is for our benefit, not his, and he is only humoring us. When the music and games stop, he picks up the tattered blue blanket in which he arrived and retreats to a corner.

“A dinner party?” I repeat, picking up the towel from the dirt.

“Yes, I used to throw them quite often before the war. I still do, from time to time. I don’t enjoy it so much anymore. The guest list—” her mouth twists “—is a little different these days. But it is important to keep up appearances.” I nod, understanding. Before the war, Krysia’s guests would have been artists, intellectuals and socialites. Most of the artists and intellectuals were gone now—they had either fled abroad or been imprisoned, because of their religion or political views, or both. They had been replaced at Krysia’s dinner table, I suspect, by guests of a far different sort.

Wiping her hands on her apron, she ticks off the guest list on her fingers. “Deputy Mayor Baran,” she pronounces the word mayor with irony. Wladislaw Baran was a known collaborator who, along with much of the present city administration, had been installed in office by the Nazis as a puppet of their regime. “The new vice director and his wife …”

“Nazis.” I turn away, fighting the urge to spit.

“The party in power,” she replies evenly. “We must keep them on our good side.”

“I suppose.” My stomach twists at the thought of being under the same roof as those people.

“You arrived several weeks ago. It would not do to have my niece living with me and not be properly introduced about town.”

“B-but …” I stammer. I had not realized Krysia expected me to be at the dinner. I had envisioned hiding upstairs for the duration of the party, or at most helping in the kitchen.

“Your presence is essential.” And I know from her tone that there will be no further discussion on the subject.

No sooner has Krysia spoken of the dinner party than the preparations begin, and they continue nonstop all week. For the occasion, Krysia brings back Elzbieta, the ruddy-cheeked housekeeper she had dismissed before my arrival. She returns without hard feelings, all energy and smiles, and immediately sets about scrubbing the house from top to bottom, putting my and Krysia’s housekeeping efforts to shame.

Krysia is glad to have Elzbieta back again, I can tell, and not just for her cooking and cleaning skills: Elzbieta’s boyfriend, Miroslaw, has a particular gift for procuring items that can no longer be found in the shops, delicacies we will need for the party. Within two days, he magically produces smoked salmon, fine cheeses and dark chocolate. “I haven’t seen such items since before the war!” Krysia exclaims upon receiving the bounty. I can only nod; I have seldom seen such things in my life. To round out the meal, we pillage the garden, pulling up the few heads of lettuce that have already sprouted, bring up the remaining winter potatoes and cabbage from the root cellar, and buy from our neighbors what other vegetables we lack.

The morning of the party, Krysia helps Elzbieta to steam the fine table linen and polish the silver while I make dinner rolls and pastries. Kneading the dough, I am reminded of baking with my father. As a child, I used to grow frustrated with the resilience of the dough. No matter how hard I tried to make it take shape, long or round or flat, it always resisted, snapping stubbornly back to a nondescript mound. Only a few of my ill-shaped pastries even made it to the shelves, and those were always the last ones remaining late in the day. But now the challenge is a welcome one. I imagine my father working beside me, kneading the bread with his light, almost magical touch. His thick, gentle fingers could cajole the most stubborn dough into intricate shapes: braided challah, or hamantaschen for Purim, or obwarzanki, the crusty pretzels enjoyed by Jewish and non-Jewish Poles alike.

“Here,” Krysia says, handing me a package wrapped in brown paper later that afternoon. We are in the kitchen, having just completed a final walk-though of the house to make sure everything is in order. I look at her puzzled, then set the package down on the table and open it. It is a new dress, light blue with a delicate flowered pattern.

“It’s beautiful,” I gasp, lifting it from the paper. Until now, I have made do with old dresses of Krysia’s, pinning up the sleeves and hems to fit me. Growing up, all of my dresses were handed down or homemade. This is the first store-bought dress I have ever owned. “Thank you.”

“You’re welcome,” she says, waving her hand as though it were nothing. “Now, go get ready.”

A few hours later, I walk down the stairs once more. The house has been transformed. Scented candles flicker everywhere. Pots simmer on the stove burners under Elzbieta’s watchful gaze, giving off a delicious aroma. Soft classical music plays on the gramophone; I think I recognize it as one of Marcin’s recordings.

At fifteen minutes to seven, Krysia descends the steps from the third floor, wearing an ankle-length burgundy satin skirt and white silk blouse, her hair drawn neatly to a knot at the nape of her long neck, which is accentuated by a single strand of pearls. She looks restored and almost untouched by the war, as if all the care and hard work of recent months have been erased from her face. “You look lovely,” Krysia says before I have the chance to compliment her. She brushes a speck of dust from my collar and then steps back to admire my dress.

“Thank you.” I blush again. I have used a hot iron to curl my hair into ringlets, which cascade down onto my shoulders. The dress is the grandest thing I have ever worn. “I wish …” I begin, then stop. I had started to say I wished Jacob were here to see me, but I hesitate, not wanting to sadden Krysia.

She smiles, understanding. “He would think you are even more beautiful than he already does.” I cannot help but beam. We walk into the dining room together. “Dinner parties are always so hectic,” she explains, reaching across the table to adjust the orchid centerpiece. “No matter how many I plan and how well I prepare, there are things that cannot be done well in advance, which makes the last few hours chaotic.”

I nod, as though I have thrown dinner parties all my life and understand. In truth, the few I had attended had been with Jacob, and they had in no way prepared me for this. Tonight is my debut as Anna Lipowski, the gentile orphan girl from Gdansk. Since leaving the ghetto, I have scarcely spoken with anyone outside of the household, and I am terrified about my first full-fledged interaction in my new role. In my head, I have rehearsed my life story over and over again. Krysia has worked with me over the past several weeks, refining my behavior and mannerisms to fit the part, helping me to adjust the last few inflections and pronunciations to ensure that I speak with the generic accent of northwestern Poland. She has also schooled me intensely in Catholicism and I now know as much about saints and rosaries as any Polish girl outside of a convent. Still, I worry that some flash across my face or look in my eye, some gesture or intangible thing will scream out that I am a Jew.

But there is little time to be nervous. A few minutes after we enter the dining room, the doorbell rings. “Ready?” Krysia asks me. I gulp once, nod. The guests begin to arrive with a promptness characteristic of both Poles and Germans. Elzbieta meets them at the door and takes their wraps and coats. I wait at the first-floor landing with Krysia, who introduces me, and then I lead the guests into the sitting room and offer them a cocktail. Lukasz is trotted out briefly and admired for his blond hair and good behavior before being shuttled off to bed.

At ten past seven, five of our six guests are present: Deputy Mayor Baran and his wife, and three Germans: General Dietrich, an elderly widower who was highly decorated in the Great War, and whose role in the present administration is largely ceremonial; Brigadier General Ludwig, a fat, bald, squinty-eyed man; and his wife, Hilda.

Ten minutes pass, then twenty, and still we are one guest short. No one comments on his lateness, and I know we will not be sitting down to eat without him. As Krysia told me earlier, Georg Richwalder, second in charge of the General Government, is the most important guest of all.

“How are you finding Kraków, Anna?” Mrs. Baran asks as we sit sipping our glasses of sherry.

“Lovely, though I haven’t had as much time to see the city as I would like,” I reply, amused at the notion of being a tourist in the city of my birth.

“Well, you and Lukasz must come into town one day soon and I will show you around. I’m surprised we haven’t met at church,” Mrs. Baran continues. I hesitate, uncertain how to respond.

Krysia steps up behind me, intervening. “That’s because we haven’t been yet. It’s been so hectic with the children arriving, I haven’t gone myself. And last week Lukasz had a cold.” I look up at her, trying to mask my surprise. Since coming to live with us, the child has not had so much as a sniffle. It is the first time I have heard Krysia lie.

“Perhaps we can have tea one Sunday after mass,” Mrs. Baran suggests.

I smile politely. It is not difficult to keep up appearances with such small talk. “That would be delight …” I start to reply, then stop midsentence, staring at the doorway.

“Kommandant Richwalder,” Mrs. Baran whispers under her breath. I nod, speechless, unable to take my eyes off the imposing man who has entered the room. He is well over six feet tall, with perfectly erect posture and a thick, muscular chest and shoulders that seem ready to burst out of his military dress uniform. His large, square jaw and angular nose appear to be chiseled from granite. I cannot help but stare. I have never seen a man like the Kommandant before. He looks as though he has stepped off the movie screen or out of the pages of a novel, the epic hero. No, not a hero, I remind myself. The man is a Nazi.

Krysia crosses the room to greet him. “Kommandant,” she says, accepting his kisses on her cheek and the bouquet of gardenias he offers. “It is an honor to meet you.” Her voice sounds sincere, as though she is speaking to a friend.

“I’m sorry to keep you waiting, Pani Smok.” His voice is deep and resonant. His head turns and he seems to swallow the entire room in his steely blue-gray eyes. His gaze locks on me. “You have a beautiful home.” I look away, feeling the heat rise in my cheeks.

“Thank you,” Krysia replies. “You aren’t late, dinner is just ready. And please call me Krysia.” She takes the Kommandant by the arm and, deftly sidestepping the other guests who have risen to greet him, leads him to me. “Kommandant, allow me to present my niece, Anna Lipowski.”

I leap to my feet, far more light-headed than I should be from two small sips of alcohol. Up close, Kommandant Richwalder is even taller than he first appeared; my head barely comes to his shoulder. He takes my extended hand in his much larger one, sending a jolt of electricity through me, making me shiver. I hope that he has not noticed. He raises my hand smoothly, barely grazing it with his thick, full lips. Though his head is bowed, his eyes do not leave mine. “Milo mi poznac.” His Polish, though stiff and heavily accented, is not altogether poor.

I feel my cheeks burn. “The pleasure is mine,” I respond in German, unable to look away.

The Kommandant’s eyebrows lift in surprise. You speak …?” He does not finish the sentence.

“Yes.” My father, who had been raised in a town by the German border, had taught me the language as a girl, and given its close linguistic relation to Yiddish, it had come easily to me. When I arrived at Krysia’s house, she suggested that I refresh my knowledge of the language. It only made sense that a girl from Gdansk, which had once been the German city of Danzig, would be bilingual.

“Herr Kommandant,” Krysia interrupts. With seemingly reluctance, the Kommandant turns to her so that she can introduce him to the other guests. Grateful that the introduction is over, I leave the room and step into the kitchen to recompose myself. What is wrong with me? I pour a glass of water and take a small sip, my hands shaking. You are probably just nervous, I tell myself, though in truth I know it is more than that—none of the other guests had such an effect on me. Of course, none of the other guests looked like Kommandant Richwalder. Picturing his steely gaze as he kissed my hand, I jump, sending water splashing over the edge of the glass.

“Careful.” Elzbieta, who had been pouring the soup into bowls, comes to me with a dry towel. Enough, I think, as she helps to blot the water that has splashed onto my dress. Compose yourself. He’s a Nazi, I remind myself sternly. And regardless, you are a married woman. You have no business having such reactions to other men. I smooth my hair and return to the parlor.

A moment later, Elzbieta rings a small bell and the guests rise. As we make our way to the dining room, I try frantically to recall the seating cards Krysia had set out. Put me next to the elderly general, I pray, or even the endlessly carping Mrs. Ludwig—just not the Kommandant. There is no way that I can maintain my composure next to him for an entire meal. But no sooner have I made my silent wish than I find myself standing on one side of the table with General Ludwig to my left and the Kommandant to my right. I try to catch Krysia’s eye at the head of the table, hoping she might somehow intervene, but she is speaking with Mayor Baran and does not notice. “Allow me,” the Kommandant says, pulling out my chair. His pine-scented aftershave is strong as he hovers over me.

Elzbieta serves the first course, a rich mushroom soup. My hand shakes as I lift the spoon, causing it to clink against the side of the bowl. Krysia discreetly raises an eyebrow in my direction, and I hope that no one else has noticed.

“So,” General Ludwig says over my head to the Kommandant. “What is the news from Berlin these days?” I am grateful that he has chosen to leave me out of the conversation, relieving me of the need to speak for a time.

“We are having success on all fronts,” the Kommandant replies between spoonfuls of soup. Inwardly, I cringe at the news that the Germans are faring well.

“Yes, I heard the same from General Hochberg,” Ludwig replies. I can tell from the way Ludwig emphasizes the name that he hopes it will impress the Kommandant. “I have heard talk of an official visit from Berlin?” He ends the sentence on an up note, then looks at the Kommandant expectantly, waiting for him to confirm or deny the rumor.

The Kommandant hesitates, stirs his soup. “Perhaps,” he says at last, his face impassive. Looking at him more closely now, I notice two scars on his otherwise flawless face. There is a deep, pale line running from his hairline to his temple on the right side of his forehead, and another, longer but less severe, traveling the length of his left jawbone. I find myself wondering how he got them, an accident perhaps, or a brawl of some sort. Neither explanation seems plausible.

“So, Miss Anna,” the Kommandant says, turning to me.

I realize that I have been staring at him. “Y-yes, Herr Kommandant?” I stammer, feeling my cheeks go warm again.

“Tell me of your life back in Gdansk.” As Elzbieta clears the soup bowls, I recount the details I have been taught: I was a schoolteacher who was forced to quit my job and move here with my little brother when our parents were killed in a fire. I recount the story with so much feeling that it almost sounds real to me. The Kommandant listens intently, seemingly focused on my every word. Perhaps he is just an attentive listener, I think, though I have not noticed him so engaged in conversation with anyone else at the party. “How tragic,” he remarks when I have finished my story. His eyes remain locked with mine. I nod, unable to speak. For a moment, it seems as though the rest of the guests have vanished and it is just the two of us, alone. At last, when I can stand it no longer, I look away.

“And you, Kommandant, where are you from?” I ask quickly, eager to take the focus off myself.

“The north of Germany, near Hamburg. My family is in the shipping business,” he replies, still staring intently at me. I can barely hear him over the buzzing in my ears. “I was orphaned at a young age, too,” he adds, as though our purportedly mutual lack of parents gave us a special bond. “Though mine died of natural causes.”

“And what is it you are doing here?” I ask, amazed at the audacity of my own question. The Kommandant hesitates, caught off guard; clearly, he is accustomed to people knowing his role.

Ludwig interjects, “The Kommandant is Governor Frank’s deputy, second in charge of the General Government. What the governor decrees, the Kommandant ensures that the rest of us implement.”

The Kommandant shifts uneasily in his chair. “Really, General, you are overstating it a bit. I am just the owner of a shipping company doing his service to the Reich.” He looks away, and I notice that his dark hair is flecked with gray at the temples.

“Not at all,” Ludwig persists, his fat face red from too much wine. “You are far too modest, sir.” He looks down at me. “Kommandant Richwalder was decorated for his valor at sea as a young man in the Great War.” I nod, doing the math in my head. If the Kommandant served in the Great War, he must be at least forty-five years old, I think, surprised. I had taken him for younger. “He was gravely injured, and he served Germany with great distinction.”

Looking at the Kommandant’s face once more, I realize then that his scars likely came from battle. He touches his fingertips to his temple then, his eyes locked with mine, as though reading my thoughts. “Please pass the salt,” I say abruptly, forcing him at last to turn away.

But Ludwig is not through with his praise of the Kommandant. “Most recently, he served the Reich overseeing Sachsenhausen with remarkable efficiency,” he adds. I have not heard of Sachsenhausen, but Ludwig says the name as though its nature is self-evident, and I do not dare to ask what it is.