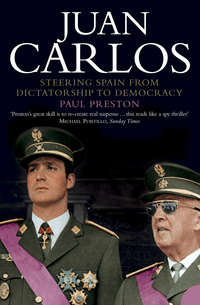

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

On 19 December, the day after this disagreeable encounter, there was an informal meeting of several of Don Juan’s Privy Council. One after another, the Marqués Juan Ignacio de Luca de Tena, Pedro Sainz Rodríguez and others spoke against the idea of the Prince being educated at Salamanca, implying that it was a dangerous place, full of foreign students and left-wing professors.100 This was most vehemently the view of the Opus Dei members, Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora and Florentino Pérez Embid. Fernández de la Mora and Sainz Rodríguez proposed that Juan Carlos be tutored at the palace of Miramar, in San Sebastián, by teachers drawn from several universities. Martínez Campos pointed out that Salamanca had been chosen for its historic traditions and for its position midway between Madrid and Estoril. He explained that his meticulous preparations – including the nomination of military aides to accompany the Prince – obviated all of the problems now being anticipated. He was mortified when, with a silent Don Juan looking on, the others furiously dismissed his arguments. At this humiliating evidence of his declining influence over Don Juan, he resigned. This occasioned considerable distress for Juan Carlos, who had become increasingly attached to his severe tutor. Over the next three days, the Prince made great efforts to persuade him to withdraw his resignation, as did his father. However, the fiercely proud Martínez Campos was not prepared to accept an improvised scheme dreamed up by Sainz Rodríguez, Pérez Embid and Fernández de la Mora.

Martínez Campos pointed out the dangers inherent in what Don Juan was doing – after all, Juan Carlos was an officer in the Spanish forces and Franco could post him wherever he liked, including Salamanca. Don Juan responded by asking him to accept the formal nomination of head of the Prince’s household, effectively the job that he had done for the previous five years. Concerned above all for his own dignity, Martínez Campos categorically refused to overturn his own plan and then supervise the implementation of the scheme of three men for whom he had little or no respect. He claimed that Don Juan’s vacillations would constitute irreparable damage to the image of the monarchy within the Army and in Spain in general. Furthermore, he argued that Franco would see this as evidence that Don Juan was ‘easily swayed by outside influences and pressures’. Don Juan ignored these warnings and gave him an envelope sealed with wax to take to El Pardo. It contained a letter to Franco explaining his change of mind. On the evening of 23 December 1959, General Martínez Campos took the overnight train to Madrid. On the following morning, he went directly from the station to El Pardo. Franco received him cordially and commented only that he was not surprised, ‘bearing in mind those who were always in Estoril. But, if he received the news with a shrug, his closest collaborators were in no doubt that he was mightily displeased.101

The entire episode provided further proof that Juan Carlos was little more than a shuttlecock in a game being played by Don Juan and Franco. In 1948, he had been unfeelingly separated from Eugenio Vegas Latapié, the tutor of whom he was deeply fond. Having come to like, respect and rely on Martínez Campos during their six years together, the process was now repeated. Once more to lose his mentor and to be reminded that his interests were entirely subordinate to political considerations carried considerable emotional costs for Juan Carlos. He said later ‘The Duque’s [Martínez Campos’s] departure distressed me considerably, but there was nothing I could do for him. Nobody had asked for my opinion. It was as if I was on a football pitch. The ball was in the air and I had no idea where it was going to fall.’ It is indicative of the Prince’s relationship with his mentor that he made a point of spending time with him in the final days of his fatal illness in April 1975.102

There can be no doubt that the clash between Don Juan and Martínez Campos had enormous significance for the future of both the Prince and his father. Major Alfonso Armada Cornyn, who had worked for Martínez Campos in overseeing the Prince’s secondary education, wrote later that this episode was the definitive cause of Don Juan’s elimination from Franco’s plans for the succession. Luis María Anson, a declared admirer of Don Juan’s senior adviser, claimed that the clash at Estoril had been deliberately planned by Sainz Rodríguez in order to provoke Martínez Campos’s resignation, ‘one of his most audacious and farsighted political masterstrokes’. In Anson’s interpretation, Sainz Rodríguez believed that, in tandem with Martínez Campos, Juan Carlos would be highly vulnerable to the machinations of hostile elements of the Movimiento. By engineering the departure of the general, Sainz Rodríguez was manoeuvring Juan Carlos into the orbit of Carrero Blanco and López Rodó.103 In fact, the efforts of Don Juan and Juan Carlos himself to get Martínez Campos to withdraw his resignation make this difficult to believe. Moreover, López Rodó had already begun to throw his efforts behind the candidacy of Juan Carlos as successor. Rather than a farsighted and cunning plan on behalf of Juan Carlos, the manoeuvres of Sainz Rodríguez, Fernández de la Mora and Pérez Embid suggest a desperate attempt at preventing the Prince from eclipsing Don Juan as Franco’s successor. Sainz Rodríguez was concerned that, under the guardianship of Martínez Campos, Juan Carlos was being too smoothly integrated into Francoist plans for the future. In any case, whatever the aims of the choreographed ambush of Martínez Campos at Estoril, it merely consolidated Franco’s conviction that Don Juan was too easily influenced by advisers.

Indeed, one of the first consequences of the break with Martínez Campos was that General Alfredo Kindelán would resign as president of Don Juan’s Privy Council. A man of great dignity and prestige, Kindelán was replaced in early 1960 by the altogether more pliant and sinuous José María Pemán. The Opus Dei members Rafael Calvo Serer and Florentino Pérez Embid assumed key roles.104 In the meantime, there ensued a lengthy correspondence that would give an entirely different tone to the contest between the Caudillo and Don Juan regarding Juan Carlos. If there had previously been any doubt, the interchange would make it unmistakably obvious that Franco was viewing the Prince as a direct heir while his father saw him as a pawn in his own strategy to reach the throne. The letter entrusted by Don Juan to Martínez Campos began with an expression of gratitude for Juan Carlos’s passage through the three military academies and for General Barroso’s generous speech in Zaragoza. Don Juan went on to refer to his deepening anxieties about the next stage of the Prince’s education. He repeated most of the arguments that had been put to Martínez Campos over the previous few days. What he was saying echoed the advice received from Sainz Rodríguez, Fernández de la Mora, Pérez Embid and others, including Rafael Calvo Serer. He referred to this group as ‘many people of great intellectual standing and healthy patriotism’. Alleging that Martínez Campos had hurried him into accepting the Salamanca scheme, he expressed the view that it would be better for the Prince to receive private classes from professors of many universities. Accordingly, he would prefer his son to be established in a royal residence with total independence.105

On the following day, Don Juan sent the Caudillo an explanatory note together with a new plan of studies. In it, Don Juan stated somewhat implausibly, ‘I want to emphasize that the delay in making the final decision that the Prince should not follow his civilian studies in Salamanca is not in any way a sudden improvisation nor mere caprice on my part.’ In justification of this statement, he alleged that Martínez Campos had gone ahead and made concrete plans despite his orders to the contrary. The plan itself, disparaging the University of Salamanca and its professors, was covered in the fingerprints of the same men who had confronted General Martínez Campos in Estoril.106

Franco’s reply in mid-January was only mildly reproachful. He began by saying that he respected the Pretender’s decision while pointing out that the grounds on which it was based were highly dubious. He went on to say that further delay would be damaging to the Prince since it would break the habit of study, ‘to which I understand he is little inclined, preferring as he does practical activities and sport’. He then suggested that the Miramar palace in San Sebastián was totally unsuitable since it was too far removed from the great university centres and its damp climate would discourage hunting. Instead he proposed a location nearer Madrid, preferably the Casa de los Peces in El Escorial. ‘This would allow me, at the same time, to be able to see the Prince more often and to keep an eye on his education, which, as far as possible, I want to look after personally.’ He then announced that he had commissioned the Minister of Education, Jesús Rubio García-Mina, to draw up a full educational plan for the Prince and a team of professors from Madrid University to undertake the task.107

Don Juan discussed this letter with Pemán, who saw Franco’s desire to see the Prince frequently as ‘rather alarming’. Before talking to Pemán, Don Juan had already replied promptly at the beginning of February, accepting the idea of residence in El Escorial, suggesting a group of professors from all over Spain who might take charge of his son’s education and naming the Duque de Frías, a non-political aristocrat who was best known as president of the Madrid golf club, as head of the Prince’s household.108 Franco was quick to point out that the proposed teachers were likely to provide something approaching a liberal education. While that might be fine for ‘just any Spaniard’, something altogether more specific was required for the Prince. ‘It is necessary to complete the education of the Prince in those civilian subjects that are basic to his future decisions.’ He went on to explain that the coldly abstract education provided by a group of unworldly scholars would be entirely unsuitable. What was necessary, he declared, was a plan based on the principles of the Movimiento. From this he went on to say that he had noted that Don Juan had advisers who seemed to harbour the absurd idea that the monarchy could change the nature of the regime. As far as Franco was concerned, the contrary was self-evidently the case. The Caudillo had chosen the monarchy to succeed him precisely in order to prolong, not alter, his regime.

Franco had not been concerned while the Prince was in one or other of the military academies, ‘temples of patriotic exaltation and schools of virtue, of character-building, of the exercise of command, of discipline and of the fulfilment of duty’. ‘In the light of all this, and given the age of the Prince, I believe that the education of Juan Carlos over the next few years is more a question of State rather than one concerning a father’s rights and it is the State that should have priority in deciding the overall educational plan and the necessary guarantees.’ He suggested that the Prince’s director of studies should be a history professor who had fought in the Civil War with the Requetés, the ferocious Carlist militia that had played a crucial role in Franco’s war effort, was a member of the Opus Dei and was now a priest – a reference to the deeply conservative Federico Suárez Verdeguer. Should Don Juan disagree, Franco was contemplating putting the entire matter of the Prince’s education in the hands of the Consejo del Reino. Franco closed the letter with the ominous statement that he would consider a meeting to discuss the details only after certain misunderstandings had been cleared up, given that what separated them was a major issue of principle.109

Don Juan’s reply was conciliatory. This reflected the role played in its drafting by the newly installed president of his Privy Council, José María Pemán. According to Pemán himself, he had been selected for the job precisely because he had no political ambitions of his own and he got on well with Franco. Now, to Don Juan’s text, he added what he called ‘the perfume so necessary for El Pardo’.110 Don Juan seems not to have perceived that Franco’s growing interest in the boy was as his direct successor not as the eventual heir to his father. The letter began by recognizing that ‘it would be absurd for him not to receive an eminently patriotic education, inspired in the same loyalty to the fundamental principles of the Movimiento that he had imbibed in the military academies’. He recognized that the interests of the State should be paramount. He accepted Franco’s suggestion of Suárez Verdeguer and other professors. Regarding the issue of whether the monarchy would try to alter the Francoist State, he engaged in an extraordinary juggling act. Recognizing that some of his supporters wanted a parliamentary monarchy, while others such as the Carlists were virulently opposed to it, he still claimed that his loyalty to the principles of the Movimiento was unquestionable. He also called, rather optimistically, for Franco to make a declaration that: ‘the way in which the Prince’s education is taking place does not prejudge the question of the succession nor alter the normal transmission of dynastic obligations and responsibilities.’ Pemán had already begun some behind-the-scenes negotiations with a sympathetic Carrero Blanco. That they had borne fruit was revealed in Franco’s reply nearly four weeks later in which he offered a meeting on 21 or 22 March at the Parador of Ciudad Rodrigo near the Portuguese border.111

News of the impending meeting stimulated rumours that major decisions about the future were imminent. Franco was now 67 and gossip was rife that his health was failing. On returning in his Rolls Royce from a hunting party in Jaén on 25 January 1960, a fault in the heating system had led to the rear of the car being filled with exhaust fumes. Noting his drowsiness, Doña Carmen had the presence of mind to order the car stopped before any serious harm was done. Wild rumours circulated within the regime, although Franco assured Pacón that he had suffered only a severe headache. Nevertheless, particularly after an announcement from the Rolls Royce Motor Car Company that exhaust gases could enter the car only if there had been deliberate tampering, the incident provoked speculation that something sinister had happened.112 So, when news of the proposed meeting at Ciudad Rodrigo was broadcast on foreign radio stations and leaked in the press, gossip raced around Madrid that Franco planned to hand over power to Don Juan. Journalists, radio reporters and newsreel cameramen descended on the border town ready to flash the news to the world’s capitals. Deeply irritated, Franco postponed the meeting for seven days and changed the venue.

Franco was infuriated by the rumours that he assumed to have emanated from Estoril and the change of venue was meant as a reprimand for Don Juan. Nevertheless, given the eager talk about Franco’s mortality, enormous significance was read into Franco’s third meeting with Don Juan, their second at Las Cabezas, on 29 March 1960.113 Las Cabezas had been inherited, on the Conde de Ruiseñada’s death, by his son, the Marqués de Comillas. Talking to Pacón before the meeting, Franco made it quite clear how little he planned to offer. He stated categorically, ‘as long as I have my health and my mental and physical faculties, I will not give up the Headship of State.’114

Pedro Sainz Rodríguez was beginning to suspect that not only would Franco not relinquish power before his death but that he would also pick as successor someone other than Don Juan. Of the various competing candidates, Juan Carlos would be preferable, but Don Juan had no desire to lose the throne even to his son. Accordingly, in his preparatory notes for the Pretender, Sainz Rodríguez argued that he must insist that: ‘the presence of the Prince must not be used to carry out manoeuvres suggesting that there is any agreement by which the order of succession can be altered.’ This threat came to be referred to by Sainz Rodríguez as ‘balduinismo’ – a reference to King Baudouin of Belgium who had ascended the throne in 1951 after the abdication of his father, Leopold III.115

A grey-suited Franco arrived with a staff of 82 in a convoy of 11 Cadillacs. He was accompanied by the Ministers of Education and Public Works, as well as numerous security guards and aides, two cooks and a doctor. Apart from the driver, Don Juan was accompanied only by his private secretary, Ramón Padilla, and the Duque de Alburquerque. In contrast with their two previous meetings, the Caudillo manifested somewhat less interest in bringing Don Juan around to his point of view, having already eliminated him as a possible successor. In the event of ever needing to organize a rapid succession process, Franco had long since decided not to offer the throne to Don Juan. Rather, he would pick Juan Carlos and simultaneously ask Don Juan to abdicate, confident that he would agree rather than risk a public break with his son. For some time to come, he would astutely refrain from making that decision public, convinced that if he did so, Juan Carlos would side with his father. Nevertheless, the notion underlay his agenda at Las Cabezas which went no further than criticism of Don Juan’s collaborators and discussion of the details of the Prince’s remaining education. Don Juan, for his part, firmly expressed his concern at the way Franco was seemingly fostering the claims of other pretenders to the throne. It was no small triumph when he successfully pressed Franco to admit that some of them (certainly Don Jaime) were receiving financial support from the Secretary-General of the Movimiento.

Don Juan complained vigorously about the continuing anti-monarchist propaganda in Spain. In particular, he protested about a book, Anti-España 1959, published in Madrid by an obsessive regime propagandist, Mauricio Carlavilla, who was also a secret policeman. The book denounced the monarchist cause as the stooge of freemasonry and a smokescreen for Communist infiltration, as well as insinuating that Don Juan himself was a freemason. Hundreds of copies had been sent by the Movimiento to people in official positions. Don Juan knew that the censorship apparatus would not have permitted the book to be distributed while Juan Carlos was resident in Spain without the Caudillo’s connivance. Now, Franco, who could plausibly have feigned ignorance, once again claimed evasively that he had no control over the press. He asserted that patriotic journalists must have seen the book as a reply to the memoirs of the monarchist aviator Juan Antonio Ansaldo, published in Buenos Aires in 1951.116

This revealed that, even if Franco had not commissioned Carla-villa’s book, he certainly approved of its contents. Ansaldo’s ¿Para qué …? (For What?) had referred to Franco as ‘the usurper of El Pardo’ and attacked his failure to restore the monarchy as a betrayal of the sacrifices made in the Civil War against the Republic. Don Juan pointed out that there was little need for a reply to a book that had been banned in Spain. He went on to complain about the constant attacks to which the monarchy had been subjected by the Movimiento press over the previous 15 years. Implying again that the press was beyond his control, Franco shiftily attributed these criticisms to indignation over the 1945 Lausanne Manifesto on the part of journalists. Franco exposed his identification with Carlavilla’s views by referring bitterly to members of Don Juan’s Privy Council as ‘traitors’. He spent 25 minutes criticizing Pedro Sainz Rodríguez as a freemason, to which Don Juan replied that nothing that he had heard could persuade him that his piously Catholic adviser could be a mason. Somewhat rattled by this, Franco replied darkly that he knew of other masons in Don Juan’s circle including his uncle ‘Ali’ – General Alfonso de Orleans Borbón – and the Duque de Alba. When Don Juan burst out laughing at this, Franco finally desisted.

The remainder of the interview dealt with the education of Juan Carlos. Franco suggested that, while he would start off with a residence in El Escorial, he should soon move to the palace of La Zarzuela. Just outside Madrid, on the road to La Coruña, La Zarzuela was very near to Franco’s own residence at El Pardo. The interest shown by the Caudillo in this respect led Pemán to note in his diary, ‘La Zarzuela is being prepared for him and Franco is personally taking charge of its furnishing like a doting grandfather.’ Franco also suggested that Juan Carlos should work in Admiral Carrero Blanco’s Presidencia del Gobierno although nothing came of this suggestion. He agreed to the appointment of the Duque de Frías as the head of Juan Carlos’s household. There was then a detailed discussion of a list of members of the ‘study committee’ that was to oversee the Prince’s civilian education. Franco had brought a list with him, which included names such as that of Adolfo Muñoz Alonso, the Falangist head of the same censorship organization that had permitted the publication of Carlavilla’s book and of endless attacks on the monarchy. In this part of the conversation, Don Juan commented later, Franco was more flexible than in previous meetings: ‘he abandoned his usual dogmatic style of a schoolteacher dealing with an ignorant schoolboy.’ Franco, in contrast, told Pacón later that: ‘I said to Don Juan everything that I had to say to him and that he had to hear.’

Just before Franco rose to leave, Don Juan gave him the text of a proposed communiqué prepared by Sainz Rodríguez, in line with the notes that he had drawn up before the meeting. It stated that the talks had taken place in a cordial atmosphere and repeated once more that Juan Carlos’s education in Spain ‘does not prejudge the question of the succession nor prejudice the normal transmission of dynastic obligations and responsibilities’. It closed with the statement that ‘the interview ended with the strengthened conviction that the cordiality and good understanding between both personalities is of priceless value for the future of Spain and for the consolidation and continuation of the benefits of peace and the work carried out so far’. A visibly displeased Franco read the text and discussed it at length with Don Juan. He argued the text point by point. He protested at a reference to Juan Carlos as Príncipe de Asturias. Acceptance of that title would have signified public recognition that Don Juan was the King, so Franco slyly claimed that it was inadmissible on the grounds that it had not been ratified by the Cortes. Don Juan conceded the point.

The discussion grew more conflictive over the statement that Juan Carlos’s presence in Spain had no implications for the succession to the throne. Franco balked at this, saying it was ‘duro’ (harsh). Don Juan replied that this was, for him, the central issue and he insisted that it, or a similar sentence, must appear in the communiqué. The Caudillo continued to make objections until Don Juan said with studied weariness, ‘Well, General, if for whatever reason you find this note to be inopportune, I’m in no hurry. The academic year is well advanced, so I could keep the boy with me until October.’ At that, Franco accepted the text with alacrity.117 Don Juan returned to Estoril, convinced that he had scored an important victory. On the following day, his staff went ahead and issued the agreed text in good faith. However, to their astonishment, the version that every Spanish newspaper was obliged to publish contained significant variants from Don Juan’s text. On arriving at El Pardo late on 29 March, Franco had unilaterally amended the agreed communiqué.118

He added a reference to himself as Caudillo, a title never acknowledged by Don Juan. To the phrase which made it clear that Juan Carlos’s presence in Spain had no bearing on the transmission of dynastic responsibilities, he added ‘in accordance with the Ley de Sucesión’. He thereby gave the impression that Don Juan now accepted the law, which in fact he repudiated. In the last sentence, he removed the phrase ‘both personalities’ lest he and Don Juan should be seen to be on an equal footing. Finally, he added to the reference to ‘the work carried out so far’ the words ‘by the Movimiento Nacional’, thereby implying that Don Juan was fully committed to it and that future relations between them would take place in that context.119 This last phrase, and the reference to the Ley de Sucesión, were generally interpreted as clear acceptance by Don Juan of Franco’s system. According to the British Ambassador, the entire political élite was ‘scrutinising the communiqué as if it were a Dead Sea Scroll’.120