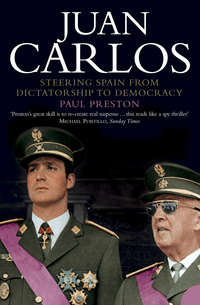

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

Madrid was buzzing with rumours and Franco quickly jumped to the conclusion that Bautista Sánchez was fostering the strike to facilitate a coup in favour of the monarchy. After his summer-time conversation with Barroso about Operación Ruiseñada, Franco was deeply suspicious of the monarchists. In fact, there was little or no chance of military action despite the wishful thinking of Ruiseñada, Sainz Rodríguez and others. However, the conversations between the royalist plotters and Don Juan’s house in Estoril were being tapped by the Caudillo’s security services, and Franco reacted to the transcripts of these optimistic fantasies as if they were fact.48 He sent two regiments of the Foreign Legion to Catalonia, under his own direct orders, to join in military manoeuvres being supervised by Bautista Sánchez. Franco also sent Bautista Sanchez’s friend, the Captain-General of Valencia, General Joaquín Ríos Capapé, to talk him out of his support for Operación Ruiseñada. The Minister for the Army, General Agustín Muñoz Grandes, also appeared in the course of the manoeuvres and confronted Bautista Sánchez with the news that he was being relieved of the command of Captain-General of Barcelona. On the following day, 29 January 1957, Bautista Sánchez was found dead in his room in a hotel in Puigcerdá.49 Wild rumours proliferated that he had been murdered – possibly even shot by another general, perhaps given a fatal injection by Falangist agents.50 A long-term sufferer of angina pectoris, it is more likely that Bautista Sánchez had died of a heart attack after the shock of his painful interview with Muñoz Grandes.51

Meanwhile, Juan Carlos was undergoing the process of getting over the tragedy of Alfonsito’s death. He seems to have adopted a forced gaiety and, understandably for a young man of nearly 19, spent as much time as his studies permitted in the company of girls. There were many of them and he had a readiness to think himself in love. He oscillated between being infatuated with, and just being very fond of, his childhood friend, Princess María Gabriella di Savoia. Neither Franco nor Don Juan approved of the relationship, among other reasons because she was the daughter of the exiled King Umberto of Italy, who had little prospect of recovering his throne.52 However, in December 1956, during the Christmas holidays at Estoril, Juan Carlos met Contessa Olghina Nicolis di Robilant, an extremely beautiful Italian aristocrat and minor film actress, who was friendly with María Gabriella and her sister Pia. She was four years older than him. His infatuation was instant and, before the night was over, he had told her that he loved her. They began a sporadic affair that lasted until 1960. She found him passionate and impulsive, not at all what she expected after what she had heard about the tragedy of Alfonsito. ‘Juanito,’ she later recalled, ‘did not show any signs of the slightest complex. He wore a black tie and a little black ribbon as a sign of mourning. That was all. I asked myself if it was a lack of feeling or if his behaviour was forced. Whatever the case, it seemed a little soon to be going to parties, dancing and necking.’ After responding to his advances, she asked about his relationship with María Gabriella. He allegedly replied, ‘I don’t have much freedom of choice, try to understand. And she’s the one I prefer out of the so-called eligible ones.’53

In 1988, the 47 love letters that Juan Carlos wrote to Olghina between 1956 and 1959 were published in the Italian magazine Oggi and later in the Spanish magazine Interviú. One of the letters was extraordinarily revealing both of the situation in which the 19-year-old Prince found himself and of his relative maturity and sense of dynastic responsibility. He wrote: ‘At the moment, I love you more than anyone else, but I understand, because it is my obligation, that I cannot marry you and so I have to think of someone else. The only girl that I have seen so far that attracts me physically and morally, indeed in every way, is Gabriella, and she does, a lot. I hope, or rather I think it would be wise, for the moment, not to say anything about getting serious or even having an understanding with her. But I want her to know something about how I see things, but nothing more because we are both very young.’ He repeated the message in another letter to Olghina in which he pointed out that his duties to his father and to Spain would prevent him ever marrying her.54

In her memoirs and in interviews following the publication of the letters, Olghina claimed that Don Juan had done everything possible to put obstacles in the way of the relationship. As she herself realized, Don Juan’s opposition put her in the same position as Verdi’s La Traviata, the courtesan abandoned because of the needs of her suitor’s family. In view of the innumerable lovers whose names tumble through the pages of her memoirs, Don Juan’s concern was entirely comprehensible. At one point, he stopped her being invited to the coming-out celebration in Portofino for Juan Carlos’s cousin, María Teresa Marone-Cinzano. According to Olghina, this provoked a ferocious row between Don Juan and his son, who threatened not to go to the ball. Juan Carlos eventually agreed to attend, but when he left early to go to see Olghina, there was a scuffle with his father.55

Olghina provides an interesting testimony of the Prince’s personality and convictions as he entered his twenties. She knew a passionate young man, who liked fast cars, motorboats and girls, although he never forgot his position. He was, she said, ‘very serious albeit no saint’. She declared that ‘he wasn’t at all shy, but was rather puritanical’ and that ‘he was always very honest with me’. He disliked women whom he considered too calculating or ‘of less than stringent morals’. His puritanical streak was perhaps typical of a Spanish young man of his generation – it did not prevent him ardently pressing on her his ‘hot, dry and wise lips’ nor spending nights in hotels with her. He was also very generous, even though he didn’t have much money at the time. Interestingly, Olghina claims that Juan Carlos disliked hunting – one of Franco’s favoured pastimes – because he had no desire to kill animals.56

When the interviewer suggested to Olghina that Juan Carlos’s letters gave the impression that he had been more attached to her than she to him, she replied that this wasn’t the case. The problem was, rather, that she was aware that he would never marry her. As a result, she tried to keep her distance from him. Juan Carlos, she said, ‘was very clear on the fact that his destiny was to give himself to Spain and that, in order to achieve this, he needed to marry into a reigning dynasty … Juan Carlos was convinced that he would be King of Spain.’57 It was later suggested that Olghina di Robilant blackmailed Juan Carlos. She was allegedly paid ten million pesetas by Juan Carlos for the letters, at which point she sent the originals to him but kept copies, which she then sold for publication.58

Despite his close relationship with Olghina, Juan Carlos had María Gabriella di Savoia’s photograph in his room in the Zaragoza academy. He was ordered to remove it from his bedside table on the grounds that: ‘General Franco might be annoyed if he visited the academy.’ This ridiculous intrusion of the Prince’s privacy may have been an initiative of the director of the academy rather than of Franco himself. However, Franco knew about it. That there was no respect for Juan Carlos’s privacy would be seen again in 1958. When the Prince visited the United States as a naval cadet on a Spanish training ship, he took a fancy to a beautiful Brazilian girl at one of the dances organized for the crew members. He wrote to her, only to discover later that all his letters had ended up on Franco’s desk. Again, in late January 1960, having been informed that Juan Carlos still had María Gabriella’s photograph on his bedside table, the Caudillo would call in one of the Prince’s closest aides, Major Emilio García Conde, to discuss the matter. Clearly preoccupied by the significance of the photograph, Franco said, ‘We’ve got to find a Princess for the Prince.’ He then went on to list a series of names whose unsuitability was pointed out by García Conde. When the latter suggested the daughters of the King of Greece, Franco replied categorically, ‘Don Juan Carlos will never marry a Greek princess!’ He had two objections – the fact that they were not Roman Catholics and his belief that King Paul was a freemason.59

The Caudillo felt that he had a right to interfere in the Prince’s romantic affairs. He told Pacón that he regarded María Gabriella di Savoia as altogether too free and with ‘ideas altogether too modern’. Newspaper speculation abounded about the Prince’s relationship with María Gabriella, and Juan Carlos remained keen on her for some time. It was rumoured that their engagement would be announced on 12 October 1960 at the silver wedding celebrations of Don Juan and Doña María de las Mercedes. The Prince’s choice of bride had enormous significance both for the royal family and the possible succession to Franco. The chosen candidate, irrespective of her human qualities, would have to be a royal princess, preferably of a ruling dynasty, financially comfortable and acceptable to General Franco. Sentiment would always take second place to political considerations. Some days before the anniversary party, the matter was discussed at a session of Don Juan’s Privy Council. On the basis of having enjoyed herself rather publicly at the previous spring’s Feria de Sevilla, María Gabriella was denounced as being frivolous – which José María Pemán thought ridiculous. In any case, Don Juan told Pemán: ‘I don’t think Juanito will be mature enough for at least a year or two.’60

Olghina di Robilant’s view that, already by the late 1950s, Juan Carlos believed that he would succeed Franco and thus take his father’s place on the throne was, of course, precisely the plan of Laureano López Rodó. On the reasonable assumption that there would be a monarchical succession to Franco, the Opus Dei was consolidating its links with both of the principal potential candidates. Thus, just as Rafael Calvo Serer remained close to Don Juan, so Juan Carlos was central to the far-reaching political plans of López Rodó.

In the wake of the internal dissent provoked by Arrese’s schemes, the Barcelona strike, serious economic problems and the push for an accelerated transition to the monarchy that had culminated in the death of Bautista Sánchez, Franco reluctantly decided that the time had come to renew his ministerial team. His hesitation was not just a symptom of his lifelong caution but was also a reflection of his inability to react with any flexibility to new problems. The cabinet reshuffle of February 1957 was to be a major turning point in the road from the dictatorship to the eventual monarchy of Juan Carlos. It was to open up the process whereby Franco would abandon his commitment to economic autarky and accept Spanish integration into the Organization for European Economic Co-operation and the International Monetary Fund. The weary Caudillo was ceasing to be an active Prime Minister and turning himself into ceremonial Head of State, relying ever more on Carrero Blanco as executive head of the government. The recently promoted admiral, no more versed than Franco in the ways of governing a modern economy, relied increasingly on López Rodó who, at 37 years of age, had become technical Secretary-General of the Presidencia del Gobierno.61 The long-term implications of López Rodó’s growing influence could hardly have been anticipated by Franco or Carrero Blanco, let alone by Don Juan and his son.

The detail of the cabinet changes reflected Franco’s readiness to defer to the advice of Carrero Blanco who, in turn, drew on the views of López Rodó. Indeed, such was López Rodó’s closeness to Carrero Blanco that his own collaborators came to refer to him as ‘Carrero Negro’.62 Having witnessed the ferocity of internal opposition to Arrese’s proposals, Franco now went in the other direction, clipping the wings of the Falange. The Falangists he appointed could scarcely have been more docile. Other key appointments saw General Muñoz Grandes replaced as the Minister for the Army by the monarchist General Antonio Barroso. While hardly likely to become involved in conspiracy, Barroso was infinitely more sympathetic to Don Juan than the pro-Falangist Muñoz Grandes. Most important of all was the inclusion of a group of technocrats associated with the Opus Dei. Together, López Rodó, the new Minister of Commerce, Alberto Ullastres Calvo, and the new Minister of Finance, Mariano Navarro Rubio, would undertake a major project of economic and political transformation of the regime. The implications of their work for the post-Franco future would dramatically affect the position of Juan Carlos.63

That was made clear in some astonishingly frank remarks made by López Rodó to the Conde de Ruiseñada shortly after the cabinet reshuffle. López Rodó claimed in effect that the marginalization of Franco was one of the long-term objectives of the technocrats. He told Ruiseñada that the ‘Tercera Fuerza’ (Third Force) plans of Opus Dei members like Rafael Calvo Serer and Florentino Pérez Embid (the editor of El Alcázar) were doomed to failure since, ‘it is impossible to talk to Franco about politics because he gets the impression that they are trying to get him out of his seat or paving the way for his replacement.’ He then made the revealing comment that ‘The only trick is to get him to accept an administrative plan to decentralize the economy. He doesn’t think of that as being directed against him personally. He will give us a free hand and, then, once inside the administration, we will see how far we can go with our political objectives, which have to be masked as far as possible.’64

At the end of March 1957, shortly before the first anniversary of the death of Alfonsito de Borbón, the Conde de Ruiseñada had a bust of him made and placed in the grounds of El Alamín. A number of young monarchists were invited and Luis María Anson, a brilliant young journalist and leader of the monarchist university youth movement, assuming that the bust would be unveiled by Juan Carlos, expressed concern that the occasion would be too painful for him. Anson was astonished to be told by Ruiseñada that the Caudillo had already instructed him to ask Juan Carlos’s cousin, Alfonso de Borbón y Dampierre, to preside at the ceremony. ‘I want you to cultivate him, Ruiseñada. Because if the son turns out as badly for us as his father has, we’ll have to start thinking about Don Alfonso.’ Anson reported the conversation to Don Juan. Until this time, the pretensions of Don Jaime and his son had not been taken entirely seriously in Estoril. Henceforth, there would be an acute awareness of the dangers of Franco applying the Ley de Sucesión in favour of Alfonso de Borbón y Dampierre.65

In May 1957, speaking with Dionisio Ridruejo, a Falangist poet who had broken with the regime, López Rodó revealed his concerns about the fragility of a system dependent on the mortality of Franco. López Rodó wanted to see the Caudillo’s personal dictatorship replaced by a more secure structure of governmental institutions and constitutional laws. Allegedly declaring that, in the wake of the recent cabinet changes, ‘the personal power of General Franco has come to an end’, López Rodó hoped to have Juan Carlos officially proclaimed royal successor while Franco was still alive. It was rather like Ruiseñada’s plan, except with Juan Carlos instead of Don Juan in the role of successor. Until 1968, when the Prince would reach 30, the age at which the Ley de Sucesión permitted him to assume the throne, Franco would remain as regent. To prevent the Head of State, King or Caudillo, suffering unnecessary political attrition, there would be a separation of the Headship of State and the position of Prime Minister.66 López Rodó’s optimism in this respect would be seriously dented in November 1957. At that point, he came near to being dismissed when Franco noticed that the decrees emanating from the Presidencia del Gobierno were limiting his powers.67 López Rodó’s plans for political change had to be introduced with extreme delicacy if the Caudillo were not to call an immediate halt to them. That, together with the hostility of the still powerful Falangists to the concept of monarchy, ensured that the realization of his programme would take another 12 years.

On 18 July 1957, Juan Carlos had passed out as Second-Lieutenant at Zaragoza. After showing off his uniform in Estoril, he went to visit his grandmother in Lausanne. While in Switzerland, he gave a press interview in which he stated that he regarded his father as King. His declaration of loyalty to Don Juan annoyed the Caudillo. Franco commented to Pacón, ‘just like Don Juan, the Prince is badly advised and he should keep quiet and not speak so much.’ Shortly afterwards, Juan Carlos visited Franco and the three military ministers of the cabinet. It may be supposed that the Caudillo’s displeasure at his comments to the Swiss press was communicated to him because it was a mistake he would never repeat.68

On 20 August 1957, Juan Carlos entered the naval school at Marin, in the Ría de Pontevedra in Galicia, an idyllic spot marred only by the stench from the nearby paper mills. After facing initial hostility from some of his fellow cadets, his easy-going affability and capacity for physical hardship won them over.69 While at Marín, he met Pacón, who wrote: ‘I found him an absolute delight. It is impossible to conceive of a more agreeable, straightforward and pleasant lad.’70 The Prince was unaware of López Rodó’s schemes for his future. By now, the Catalan lawyer had been asked by Carrero Blanco to draw up a set of constitutional texts which would allow the eventual installation of the monarchy, yet still be acceptable to those who wanted the Movimiento to survive after the ‘biological fact’, as the death of Franco was coming to be called. The question of the transition from the dictator to an installed monarch, and López Rodó’s draft texts, were discussed interminably in the cabinet. However, Franco had no interest in a process that he regarded as no more than fine-tuning the Ley de Sucesión. In any case, he was in no hurry to think about death.

Throughout the summer of 1957, Ruiseñada and López Rodó both tried to arrange an interview between Franco and Don Juan. Whether their agendas in doing so coincided is difficult to say. In any case, they had not consulted Don Juan previously. From Scotland, where he was on holiday, Don Juan refused on the grounds that he could see no sign of progress or reform in the regime. Indeed, on 25 June, he had sent Franco a letter and memorandum in which he stated that there was no point in a meeting until Franco was prepared to make a major step forward in planning for the future. ‘The time for a new interview will be when Your Excellency judges that the opportune moment has arrived for a significant change. Such an interview should not be limited to a mere interchange of news and ideas but rather, unless you think otherwise, should deal with the fundamental issues of Spain’s political future and this is not something that can be improvised in the course of a conversation.’ It is not difficult to imagine how the Caudillo reacted to the suggestion that Don Juan might be in a position to negotiate about the political future. His role, if any, so far as Franco saw it, was simply to swear an oath to accept the Francoist system in toto.

A reference by Don Juan to ‘the interim status of the present regime’ might also have been designed to infuriate Franco. He was equally irritated by the suggestion that the monarchy under Don Juan would deviate from the essential bases of that regime. He replied in early September: ‘The monarchy should be born as a natural and logical evolution of the regime itself towards other institutional forms of state; from a strong, authoritarian state that safeguards the national and moral values in defence of which the Movimiento Nacional emerged, and at the same time, opens the way to those new kinds of state demanded by the needs of the country and which can assure the consolidation and survival of the monarchical regime.’

Franco took the greatest offence at the implication that the future monarchy might change anything at all about his regime. He described Don Juan’s points as ‘unacceptable’ and reminded him that while constitutional plans were in place for a monarchy, nothing had been settled about the individuals who might sit on the throne. The Caudillo made it clear that there was no question whatsoever of a different conception of the State succeeding his regime. As from on high, the all-powerful master lecturing the recalcitrant servant, he wrote: ‘Herein lies the great confusion that has prompted your memorandum, not only in regard to the needs of the country and to the opinion of great sectors of the nation but also in regard to what it means to be able to forge a new legality. Our War of Liberation, with all its sacrifices, meant that the people won with their blood the situation and the regime that we now enjoy. The Ley de Sucesión came, nearly ten years later, to give written form to the legality forged by the man who saved an entire society, re-established peace and law and order and placed the nation firmly on the road to its resurgence. To call into question this long consolidated legality, to harbour reservations about what has been constituted and to try to open a constituent period, would signify a massive suicide. It would give hope to all the ambitions and appetites of the rebellious minorities and would offer foreigners and enemies from outside a new opportunity to besiege and destroy Spain.’ Such a mixture of arrogance and paranoia left no room for dialogue.71

Don Juan had just returned from his holiday in Scotland and absorbed this thunderous rebuff when López Rodó arrived in Lisbon. He was in Portugal as part of a Spanish economic delegation. At a lunch given by the Portuguese Prime Minister, Marcelo Caetano, journalists asked the Spanish Ambassador, Nicolás Franco, if it was true that the Caudillo wished Don Juan to abdicate in favour of Juan Carlos. He replied in typical gallego (Galician) fashion, ‘I’ve never heard my brother say anything about that. But I think that if he can have two spare wheels, he wouldn’t want to make do with only one.’ There can be little doubt that the exchange was reported back to Villa Giralda and can only have caused Don Juan considerable concern.

López Rodó took the opportunity of the trip to arrange a clandestine meeting with Don Juan in the centre of Lisbon at the home of a Portuguese friend. Unaware of Franco’s high-handed letter, he endeavoured to reassure Don Juan that things were moving within the regime, albeit slowly. Without admitting, as he had to Dionisio Ridruejo three months earlier, that he saw Juan Carlos as the better bet, López Rodó himself explained to Don Juan his scheme for gradual evolution. Their conversation on 17 September 1957 lasted more than three hours. López Rodó told Don Juan that, although Franco wanted to put an end to the uncertainty surrounding his succession, he was obsessed with the fear that, when he died, his life’s work could simply be jettisoned by his royal successor. Thus, in accordance with the Ley de Sucesión, whoever was chosen would have to accept the basic principles of the Francoist State. Don Juan made it clear that for him to take the first step would be, ‘like being forced to take a purgative. I wouldn’t want to be politically compromised.’ As delicately as possible, López Rodó hinted that such an attitude eliminated him from the game.72

Later on the same day, perhaps influenced by his conversation with López Rodó, Don Juan wrote a conciliatory letter to Franco. His backtracking was a clear recognition of the fact that Franco held all the cards: ‘I am deeply distressed that the interpretation which Your Excellency has given to the paragraph in my memorandum, in which I spoke of “the monarchy as a natural and logical evolution of the regime itself”, should differ so much from the meaning that I put into my words. Evolution, for me, means perfecting, completing the present regime, but the idea of opening a constituent period, or of any discontinuity between the present regime and the monarchy, has never entered my mind.’ He ended feebly by saying that, whenever Franco wished, he would be delighted to meet him.73