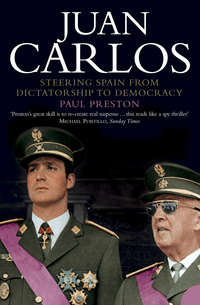

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

Signed by eight Lieutenant-Generals, Kindelán, Varela, Orgaz, Ponte, Dávila, Solchaga, Saliquet and Monasterio, the letter was handed to the Caudillo by General Varela at El Pardo (Franco’s official residence just outside of Madrid) on 15 September. In fact, the Caudillo had already been alerted to its contents by a member of Don Juan’s Privy Council, Rafael Calvo Serer. Calvo Serer was a talented, if somewhat erratic, young intellectual, and a convinced monarchist, but he was also a high-ranking member of the Opus Dei. He had insinuated himself into the inner circle of Alfonso de Orleáns Borbón and when he got hold of the draft, hastened to Franco’s summer residence, the Pazo de Meirás in Galicia. In fact, respectfully couched – ‘written in terms of vile adulation’ according to one of Don Juan’s principal advisers, the exiled José María Gil Robles – the letter was more annoying than threatening to Franco. However, it did nothing to improve his attitude to Don Juan.51

At the end of 1943, Don Juan wrote a letter to one of his most prominent followers, the Conde de Fontanar. The inflammatory text referred to Franco as an ‘illegitimate usurper’ and called upon Fontanar to break publicly with the regime. The letter fell into Franco’s hands. Don Juan had chosen as his intermediary the sleekly ambitious Rafael Calvo Serer. Later Don Juan came to believe erroneously that the letter had been given by Calvo Serer to his spiritual adviser, Padre Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer, the Aragonese priest and founder of the Opus Dei, who had then handed it to Franco. It has also been alleged that the letter was actually given by Calvo Serer to Franco’s cabinet secretary and a key adviser, Captain Luis Carrero Blanco, with the request that its ‘interception’ be attributed to the dictatorship’s intelligence services. However, the allegation remains unproved.52

The Caudillo responded to Don Juan with disdain. After a feeble lie about the letter falling into the hands of an enemy agent ‘from whom we were able to retrieve it’, he went on to patronize the Conde de Barcelona in imperious terms. He asserted that his own right to rule Spain was infinitely superior to that of Juan III: ‘among the rights that underlie sovereign authority are the rights of occupation and conquest, not to mention that which is engendered by saving an entire society.’ To devalue Don Juan’s claims, Franco stated that the military uprising of 1936 was not specifically monarchist, but more generally ‘Spanish and Catholic’ and that his regime therefore had no obligation to restore the monarchy. This sat ill with his own published justification for preventing Don Juan serving on the Nationalist side in 1937. In further defence of his legitimacy, he cited his own merits, accumulated during a life of sacrifice, his prestige among all sectors of society and public acceptance of his authority. He went on to state that Don Juan’s actions constituted the real illegitimacy because they were impeding the monarchical restoration to which the Caudillo ostensibly aspired. Franco ended by recommending that Don Juan leave him, without any time limit, to his self-appointed task of preparing the ground for an eventual restoration.

Don Juan’s reply was not without its ironic undertones. In response to Franco’s insinuation that he was out of touch with the situation in Spain, he pointed out that in 13 years of exile, he had learned more than he might living in a palace, where, he said in a pointed reference to life at El Pardo, the atmosphere of adulation so often clouded the vision of the powerful. Regarding their conflicting visions of the international situation, Don Juan pointed out that Franco was one of the very few people in 1943 to believe in the long-term stability of the National-Syndicalist State. He suggested that Franco and his regime would not survive the end of the War. To avoid a stark choice between Francoist totalitarianism and a return to the Republic, Don Juan appealed to the Caudillo’s patriotism to restore the monarchy. Once more, he repeated his argument – an anathema to Franco – that the monarchy was a regime for all Spaniards and how, for that reason, he had always refused Franco’s invitations to express solidarity with the Falange.53 Don Juan’s crystalline letter had all the logic, common sense and patriotism that was lacking in Franco’s convoluted effort. However, the Caudillo was the sitting tenant and he was determined to brazen out the situation, confident that the Allies had too many other things to worry about. His optimism was in part fed by the conviction that the Americans regarded him as a better bet for anti-Communist stability in Spain than either the Republican opposition or Don Juan.

Despite his virtually limitless confidence in his own superiority over the House of Borbón, and his belief in the legitimacy of his power by dint of the right of conquest, Franco did feel seriously threatened by Don Juan’s so-called Manifesto of Lausanne. This momentous document was issued just as the Caudillo’s faith in Axis victory was finally beginning to ebb. With Pedro Sainz Rodríguez and José María Gil Robles in Portugal, and communication with Switzerland extremely difficult, the Manifesto was drawn up largely by Don Juan himself with the assistance of Eugenio Vegas Latapié. It was a denunciation of the Fascist origins and the totalitarian nature of the regime. Broadcast by the BBC on 19 March 1945, it called upon Franco to withdraw and make way for a moderate, democratic, constitutional monarchy. It infuriated Franco and set in stone his prior determination that Don Juan would never be King of Spain. Only the tiniest handful of monarchists responded to the Manifesto’s call for them to resign their posts in the regime.54 For many monarchists, Francoist stability had come to be worth much more than the uncertainties of a restoration. Fearful that Don Juan’s confidence in Allied support threatened the overthrow of the dictatorship and the possible return of the exiled left, they were not inclined to rally actively to his cause.

Franco’s éminence grise, the naval captain Luis Carrero Blanco, short, stocky, his face overshadowed by his thick bushy eyebrows, advised him how best to exploit this sentiment. The dourly loyal Carrero Blanco recommended that he refrain from lashing out immediately against Don Juan. Instead, he counselled a process whereby the Pretender would be weaned away from his more radical advisers and coaxed into the Movimiento fold. His memorandum to Franco was astonishingly prophetic and it did not bode well for Don Juan’s future or for Juan Carlos’s happiness: ‘It is crucial to get Don Juan on the road to radical change so that, in some years, he might be able to reign, otherwise he must resign himself to his son coming to the throne. Moreover, it is necessary to start thinking about preparing the child-prince for Kingship. He is now six or seven and seems to have good health and physical constitution; if properly brought up, principally in terms of Christian morality and patriotic sentiments, he could be a good King with the help of God, but only if this problem is faced up to now. For the moment, it would be prudent, 1) given that new clashes are not in our interests and nothing good can come of them, not to react violently against Don Juan nor give up on him altogether even though we believe that he cannot now be King; 2) to send some trustworthy monarchists to Lausanne; 3 ) to put the greatest care into selecting a perfectly prepared tutor for the young Prince; 4) to face up determinedly to the problem of the fundamental laws that we need, and define the Spanish regime. With regard to choosing our definitive form of government, since nations can be only republics or monarchies, and in Spain the republic is out of the question since it is a symbol of disaster, the form of government has to be a monarchy.’55

Without the military support of the Allies or the prior agreement of the military high command and the ecclesiastical hierarchy, Don Juan was naïvely depending on Franco withdrawing in a spirit of decency and good sense. The Caudillo’s determination never to do so was revealed in his comment to General Alfredo Kindelán: ‘As long as I live, I will never be a queen mother.’56 Despite Carrero’s counsel of moderation, Franco was deeply stung by the Lausanne Manifesto. He began to take practical steps to give substance to his claims to be the best hope for the monarchy. Two prominent regime Catholics, Alberto Martín Artajo, President of Catholic Action, and Joaquín Ruiz Giménez were despatched to tell Don Juan that the Church, the Army and the bulk of the monarchist camp remained loyal to Franco. They had no need to tell him that the Falange was deeply opposed to a restoration.57 To neutralize any resurgence of monarchist sentiment in the high command, Franco summoned his senior generals to a meeting which remained in session for three days, from 20 to 22 March. He brazenly informed his generals that Spain was so orderly and contented that other countries including the United States were jealous and planned to adopt his Falangist system. He tried to frighten his generals off any monarchist conspiracy by brandishing the danger of Communism for which he blamed Britain, Don Juan’s best chance of international support. It did not bode well for the Borbón family that, Kindelán aside, the generals seemed happy to swallow the Caudillo’s absurd claims.58The controlled press praised Franco for having saved the Spanish people from ‘martyrdom and persecution’, the fate, it was implied, to which the failures of the monarchy had exposed them.59 Even more space than usual was devoted to the annual Civil War victory parade. Slavish tribute was paid to Franco’s victory over the ‘thieves’, ‘assassins’ and Communists of the Second Republic – the barely veiled message being that these same criminals – and with them, Don Juan – were even now plotting their return with the help of the Allies.60

All this time, the young Juan Carlos had been brought up by nannies and tutors, seeing more of his mother than his father, who was absorbed by the struggle to restore the throne. Now he was seven and oblivious, as were his parents, to the momentous implications of Carrero Blanco’s report on the Lausanne Manifesto. Thirty years before the death of Franco, Carrero Blanco was proposing that his master’s eventual successor be Juan Carlos. For that to be a feasible option, it would be crucial, from the dictator’s point of view, that Juan Carlos received the ‘right’ kind of political formation, or indoctrination. Don Juan’s acquiescence was crucial, yet Franco made little effort to avoid unduly antagonizing him. When the chubby Martín Artajo returned from his mission to Lausanne, Franco grilled him on 1 May for two and a half hours about his conversations with Don Juan. Still furious about the Manifesto, Franco snapped, ‘Don Juan is just a Pretender. I’m the one who makes the decision.’ The Caudillo made it patently clear that he did not believe in one of the basic tenets of monarchism – the continuity of the dynastic line. In coarse language that must have shocked the prim Martín Artajo, he dismissed what he considered to be the decadent constitutional monarchy by reference to the notorious immorality of the nineteenth-century Queen Isabel II. He said, ‘the last man to sleep with Doña Isabel cannot be the father of the King and what comes out of the belly of the Queen must be examined to see if it is suitable.’ Clearly, Franco did not regard Don Juan de Borbón as fit to be King. He made critical comments about his personal life and dismissed Martín Artajo’s efforts to defend him – ‘There’s nothing to be done … He has neither will nor character.’ Franco would produce a law which turned Spain into a kingdom but that would not necessarily mean bringing back the Borbón family. A monarchical restoration would take place, declared Franco, ‘only when the Caudillo decided and the Pretender had sworn an oath to uphold the fundamental laws of the regime’.61

Nevertheless, the imminent final defeat of the Third Reich, together with Don Juan’s pressure, impelled Franco to make a crudely cynical gesture aimed at undermining the Pretender’s position among monarchists inside Spain. Over several days in the first half of April 1945, he discussed the idea of adopting a ‘monarchical form of government’. Monarchists within the Francoist camp were thus offered a sop to their consciences, together with an assurance that they need not face the risks of an immediate change of regime. At the same time, the cosmetic change would help the Allies forget that Franco’s regime had been created with lavish Axis help. A new Consejo del Reino (Council of the King) would be created to determine the succession. Grandiosely billed as the supreme consultative body of the regime, its function was simply to advise Franco, who would have no obligation to heed its advice. Moreover, the emptiness of the gesture was exposed by the announcement that Franco would remain Head of State and that the King designated by the Consejo would not assume the throne until Franco either died or abandoned power himself. A pseudo-constitution known as the Fuero de los Españoles (Spaniards’ Charter of Rights) was also announced.

Given his messianic conviction in his own God-given right to rule over Spain, Franco could never forgive Don Juan for trying to use the international situation to hasten a Borbón restoration. He believed that, if he could buy time from his foreign enemies and his monarchist rivals with cosmetic changes to his regime, the end of the War would expose, to his benefit, the underlying conflict between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. His confidence was well-founded. On 19 June, at the first conference of the United Nations, which had been in session in San Francisco since 25 April, the Mexican delegation proposed the exclusion of any country whose regime had been installed with the help of the Armed Forces of the States that had fought against the United Nations. The Mexican resolution, drafted with the help of exiled Spanish Republicans, could apply only to Franco’s Spain and it was approved by acclamation.62 Within the Spanish political class, it was assumed that there would now be negotiations for the restoration of the monarchy.63 However, aware that, in Washington and London, there were those fearful that a hard line might encourage Communism in Spain, Franco and his spokesmen simply refused to accept that the San Francisco resolution had any relevance to Spain, making the most bare-faced denials that his regime was created with Axis help.64

Shortly afterwards, Franco would adopt a strategy aimed at reversing Don Juan’s advantage in the international arena. The Fuero de los Españoles was introduced with a speech that implied to Spaniards and Western diplomats alike that any attempt to remove or modify the regime would open the gates to Communism.65 Within one month, he reshuffled his cabinet in order to eliminate the ministers most tainted by the Axis stigma and brought in a number of deeply conservative Christian Democrats. They, and particularly the most prominent of them – Alberto Martín Artajo as Foreign Minister – permitted Franco to project a new image as an authoritarian Catholic ruler rather than as a lackey of the Axis.66

A fervent Catholic, Martín Artajo owed his appointment to the recommendation of Captain Carrero Blanco, with whom he had spent nearly six months between October 1936 and March 1937 in hiding in the Mexican Embassy in Madrid. He accepted the post after consultation with the Primate, Cardinal Plá y Deniel, and both were naïvely convinced that he could play a role in smoothing the transition from Franco to the monarchy of Don Juan.67 Franco was happy to let them believe so, but intended to maintain an iron control over foreign policy. The subservient Artajo would simply be used as the acceptable face of the regime for international consumption. Artajo told the influential right-wing poet and essayist, José María Pemán, a member of Don Juan’s Privy Council, that he spoke on the telephone for at least one hour every day with Franco and used special earphones to leave his hands free to take notes. Pemán cruelly wrote in his diary: ‘Franco makes international policy and Artajo is the minister-stenographer.’ In the first meeting of the new cabinet team, on 21 July, Franco told his ministers that concessions would be made to the outside world only on non-essential matters and when it suited the regime.68

While nonplussed by the clear evidence that Franco had no immediate intentions of restoring the monarchy, Don Juan was encouraged by the appointment of Martín Artajo, whom he trustingly regarded as one of his supporters. It was the beginning of a process in which Don Juan was to be cunningly neutralized by Franco. As part of a plan to drive a wedge between Don Juan and his more outspoken advisers, Gil Robles, Sainz Rodríguez and Vegas Latapié, Franco encouraged conservative monarchists of proven loyalty to his regime to get close to the royal camp. One of the most opportunistic of these was the sleekly handsome José María de Areilza, a Basque monarchist who had been closely linked to the Falange in the 1930s. Areilza had acquired the aristocratic title of Conde de Motrico through marriage and his impeccable Francoist credentials had been rewarded when he was named Mayor of Bilbao after its capture in June 1937. In 1941, he wrote with Fernando María Castiella, the ferociously imperialist text Reivindicaciones de España (Spain’s Claims) and had aspired to be Ambassador to Fascist Italy. After the War, he moved back to the pro-Francoist monarchist camp, and would be named Ambassador to Buenos Aires in May 1947. His visits to see Don Juan were dutifully reported to the British Embassy to give the impression that Franco was negotiating the terms of a restoration and so buy him more time.69

The wisdom of Franco’s policy, and the waning prospects of Don Juan, were both illustrated by the relatively toothless Potsdam declaration which reiterated Spain’s exclusion from the United Nations but made no suggestion of intervention against the Caudillo. Statements from the British Labour government that nothing would be done that might encourage civil war in Spain heartened the Caudillo further.70 Don Juan would have been even gloomier had he known of a report on the regime’s survival drafted at this time by Franco’s ever more influential assistant, Captain Carrero Blanco. It was a brutally realistic document which rested on the confidence that, after Potsdam, Britain and France would never risk opening the door to Communism in Spain by supporting the exiled Republicans. Accordingly, ‘the only formula possible for us is order, unity and hang on for dear life. Good police action to anticipate subversion; energetic repression if it materializes, without fear of foreign criticism, since it is better to punish harshly once and for all than leave the evil uncorrected.’ There was no place for Don Juan in that future.71 On 25 August 1945, Franco sacked Kindelán as Director of the Escuela Superior del Ejército (Higher Army College) for making a fervently royalist speech predicting that the Pretender would soon be on the throne with the full support of the Army.72

Anxious to establish control over Don Juan, in the autumn of 1945, Franco through intermediaries suggested that if the heir to the throne took up residence in Spain, he would be provided with a royal household fit for a future King. The message, passed on by Miguel Mateu Pia, the Spanish Ambassador in Paris, made it clear that Franco had no intention of any sudden change. He was merely looking for a way of placating both the Great Powers and the monarchist conspirators in the Army. Don Juan had no desire to become the Caudillo’s puppet and was still hopeful of military action to overthrow the regime. Accordingly, he rejected the offer out of hand – commenting ‘I am the King. I do not enter Spain by the back door.’ The refusal was underlined when Don Juan told La Gazette of Lausanne that the need to ‘repair the damage done to Spain by Franco’ made the restoration of the monarchy an urgent necessity. He denounced Franco’s regime as ‘inspired by the totalitarian powers of the Axis’ and spoke of his intention to re-establish the monarchy within a democratic system similar to those of Britain, the United States, Scandinavia and Holland.73

On 2 February 1946, Don Juan and his wife moved to the fashionable but sleepy seaside resort of Estoril, west of Lisbon. An area of splendid mansions built for the millionaire bankers and shipbuilders of the nearby capital, its silent isolation was disturbed only by the click of chips falling in the casinos. The eight-year-old Juan Carlos, to his considerable distress, was left behind in Switzerland, where he was by now being educated by the Marian fathers in Fribourg. For the first two months in Portugal, his family lived in Villa Papoila, loaned by the Marqués de Pelayo, later moving in March 1946 to the larger Villa Bel Ver. They stayed there until the autumn of 1947 when they moved to Casa da Rocha, until finally in February 1949, they established their residence at Villa Giralda. In 1946, for many of Don Juan’s supporters, his proximity to Spain seemed to shorten the distance that separated him from the throne. His mere presence in the Iberian Peninsula set off a wave of monarchist enthusiasm. The Spanish Foreign Ministry was inundated with requests for visas as senior monarchists set off to pay their respects.74

Franco’s Ambassador to Portugal, his brother Nicolás, quickly established a superficially cordial relationship with Don Juan. However, when Nicolás suggested he drive him to Madrid for a secret meeting with the Caudillo, Gil Robles, Don Juan’s senior adviser, was adamant: ‘Your Majesty cannot go and see Generalísimo Franco on Spanish soil since he would be going there as a subject.’75 Indeed, it had been the expectation of tension with Franco that had led Don Juan to decide that it was better for Juan Carlos to remain in Switzerland. The wisdom of his decision was underlined when the Caudillo lashed out in response to the publication on 13 February 1946 of a letter welcoming Don Juan to the Peninsula, signed by 458 prominent establishment figures. Franco reacted as if he was faced with a mutiny by subordinates rather than an attempt to accelerate a process to which he had publicly committed himself. He told a cabinet meeting on 15 February, ‘This is a declaration of war, they must be crushed like worms.’ In an astonishing phrase, he declared, ‘the regime must defend itself and bite back deeply.’ He relented only after Martín Artajo, General Dávila and others had pointed out the damaging international repercussions of such a move. He then went through the list of signatories, specifying the best ways of punishing each of them, by the withdrawal of passports, tax inspections or dismissal from their posts.76

While these high political dirty tricks were going on, the eight-year-old Prince was sent to a grim boarding school at Ville Saint-Jean in Fribourg, run by the stern Marian fathers. Juan Carlos would later recall his distress at being separated from his family and from his tutor Eugenio Vegas Latapié, of whom he had become fond. ‘At first, I was really very miserable, because I felt that my family had abandoned me, that my mother and father had just forgotten all about me.’ Every day he waited for a telephone call from his mother that never came. It must have been the harder to bear because of the gnawing suspicion that his parents’ favourite was his younger brother Alfonso, who remained at home with them. Only later did he discover that his father had forbidden his mother to phone him, saying, ‘María, you’ve got to help him become tougher.’ Later on, Juan Carlos tried to explain away his father’s actions – ‘It was not cruelty on his part and certainly not a lack of feeling. But my father knew, as I would later know myself, that princes need to be brought up the hard way.’ Juan Carlos had to pay a terrible price in loneliness – ‘in Fribourg, far from my father and my mother, I learned that solitude is a heavy burden to bear.’ The most visible consequences of the apparent harshness of his parents’ treatment would be his perpetually melancholy expression and a silent reserve.

In later endeavouring to explain away his father’s motivation, Juan Carlos inadvertently shed light on his own life as an eight-year-old, far from his parents: ‘My father had a deep sense of what being royal involved. He saw in me not only his son but also the heir to a dynasty, and as such, I had to start preparing myself to face up to my responsibilities.’77 Despite such rationalizations, it is clear that it was difficult for Juan Carlos ever to reconcile himself to this early separation. (His own son, Felipe, would not be sent to boarding school at such a young age and did not leave home for the first time until he was 16, in order to spend his last year at school at the Lockfield College School in Toronto, Canada.) Indeed, in a 1978 interview for the German conservative paper Welt am Sonntag, Juan Carlos would describe his departure for Ville Saint-Jean in more heartfelt terms: ‘going to boarding school meant saying goodbye to my childhood, to a worry-free world full of family warmth. I had to face that initial difficult period of separation from my family all alone.’78