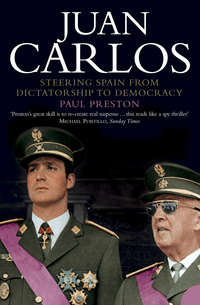

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

Juan Carlos did not know that an even more complete separation from his parents was under discussion. He had longed to return home to Estoril for the summer holidays and once there, he spent the time playing with friends, frolicking on the beach and horse riding. He had no desire to return to his boarding school in Fribourg and was thus delighted when he was allowed to stay on at Estoril. Since preparations were afoot for him to go to Spain, Don Juan saw no point in sending him back to school. Juan Carlos was in limbo, happy to be with his parents and unaware that his father was contemplating sending him as a hostage to Franco. At the beginning of October, Vegas Latapié advised Don Juan that this situation played into Franco’s hands by making it obvious that the boy was eventually going to be sent to Spain. Within 12 hours, arrangements were made for Juan Carlos’s rapid, and presumably upsetting, return to Fribourg accompanied by Vegas Latapié. In his heart, Don Juan was convinced that there could be no restoration against the will of Franco. He knew that the international situation totally favoured the Caudillo. So, the boy’s interests were made subordinate to the need for a minor political gesture.104

The advantages of the uneasy rapprochement between the dictator and Don Juan were entirely one-sided. To Franco’s satisfaction, the negotiations between monarchists and Socialists became meaningless. The so-called Pact of St Jean de Luz, so painfully constructed throughout 1948 and finally signed in October by Indalecio Prieto and Gil Robles, was the first serious attempt at national reconciliation since the Civil War. Now it was rendered stillborn. The Azor meeting completely discredited the democratic monarchist option for which moderate Socialists and Republicans had broken with the Communist Party and the Socialist left. It must have given Franco intense pleasure to read a letter, intercepted by his secret services, in which Indalecio Prieto referred to ‘the little cutey of Estoril’.105 In return, Franco merely gave Don Juan superficial respect and a stab in the back. The destabilizing effects on Juan Carlos – educational or emotional – played no part in the considerations of any of the players in this particular game.

On the occasion of Franco’s 25th wedding anniversary, Don Juan sent a message of congratulation. He took the opportunity to say that he had decided to keep Juan Carlos at his boarding school in Switzerland until the arrangements were in place for him to go to Spain. He mentioned, ‘the lively interest shown by his grandmother, Queen Victoria Eugenia, in having him with her before such a long separation’. What is remarkable is that the boy’s own parents seemed not to need to spend time with their son prior to what was likely to be a gruesome experience for him.106

The real significance of the Azor meeting was brutally revealed on 26 October when Franco arranged for news to be leaked that Juan Carlos would be educated in Spain. With no concessions from Franco other than a promise that the monarchist daily ABC could function freely and that restrictions on monarchist activities would be lifted, Don Juan was forced to put an end to his hesitations.107 On 27 October, he sent a telegram to Eugenio Vegas Latapié: ‘It is urgent that you come with the Prince as soon as possible. Stop. There are SAS and KLM flights direct to Lisbon. Stop. I’ll explain why when you arrive. Stop.’ Vegas Latapié sent a cable to Estoril pointing out that they could save a day or more by taking a flight to Madrid and then changing for Lisbon. However, Don Juan sent categoric instructions that they were not to return via Spain. A somewhat bewildered Juan Carlos made the journey as instructed and then waited aimlessly in Estoril. He was distressed when told about the plans for his education in Spain. He was especially upset when he discovered that he was not to be accompanied by his tutor. The fact was that the Caudillo, eagerly backed by Don Juan’s enthusiastically pro-Franco advisers, the Duque de Sotomayor and Danvila, did not want Vegas Latapié to have any influence on the Prince’s education in Spain. At one point, the Prince said to Vegas, ‘I’m sad that you’re not coming to Spain with me!’ Before Vegas could reply, Don Juan, perhaps feeling guilty about what he was doing to his son, interrupted brusquely ‘Don’t be stupid, Juanito!’ Doña María de las Mercedes was deeply aware of how affected her son would be by the separation from his beloved tutor. Don Juan rather feebly suggested that Vegas Latapié return to Spain in a personal capacity in order to spend time with the Prince on Sundays. Vegas sadly pointed out that a ten-year-old boy could not be expected to give up his exiguous free time to go for walks with a crusty old man.108

Vegas Latapié took his leave of Juan Carlos on 6 November as if he would be seeing him the next day. He returned to Switzerland on 7 November. At Lisbon Airport, he gave Pedro Sainz Rodríguez a letter to deliver to the Prince. ‘My beloved Sire, Forgive me for not saying that I was leaving. The kiss that I gave you last night meant goodbye. I have often told you that men don’t cry and, so that you don’t see me cry, I have decided to return to Switzerland before you go to Spain. If anyone dares tell Your Highness that I have abandoned you, you must know that it is not true. They didn’t want me to continue at your side and I have no choice in the matter. When I return to Spain for good, I will visit Your Highness. Your faithful friend who loves you with all his soul asks only that you be good, that God bless you and that occasionally you pray for me. Eugenio Vegas Latapié.’109 That such an austere and inflexible character as Vegas could be moved to write such a sad and tender letter testifies to his closeness to the Prince.

It serves to underline that, although there were many political reasons why Juan Carlos had to be educated in Spain, the entire episode could have been handled with greater sensitivity to his emotional needs. Gil Robles wrote in his diary: ‘Vegas may have his defects – who doesn’t? – but nobody outdoes him in loyalty, firmness of purpose, unselfishness and affection for the Prince. And, despite everything, with cold indifference, they just dumped him. How serious a thing is ingratitude, above all in a King!’110

It is a telling comment on Don Juan’s attitude to what was about to happen that he did not spend the day before the journey with his son. A perplexed Gil Robles wrote in his diary: ‘he’s gone hunting as if nothing was happening.’111 In an effort to ensure that there would be no demonstrations at the main station in Lisbon, the tearful ten-year-old Juan Carlos was waved off by his tight-lipped parents as he joined the Lusitania overnight express on the evening of 8 November at En troncamento, a railway junction far to the north of the capital. If there was one thing that might have diminished a ten-year-old boy’s sadness at having to leave his parents it was the possibility of a spell driving a train. However, that pleasure was monopolized by a grandee, the Duque de Zaragoza, decked out in blue overalls. For his journey into the unknown, the young Prince was accompanied by two sombre adults, the Duque de Sotomayor, as head of the royal household, and Juan Luis Roca de Togores, the Vizconde de Rocamora, as mayordomo.

At first Juan Carlos dozed fitfully but then slept as the train trundled in darkness through the drought-stricken hills of Extremadura. As they entered New Castile in the early light of dawn, he was awakened by the Duque. Burning with curiosity about the mysterious land of which he had heard so much but never visited, he pressed his face to the window. What he saw bore no resemblance to the deep greens of Portugal. Juan Carlos was taken aback by the harsh and arid landscape. Austere olive groves were interrupted by scrubland dotted with rocky outcrops. As they neared Madrid, the boy’s impressions of the impoverished Castilian plain were every bit as depressing. He did not know it yet, but he was saying goodbye to his childhood. What awaited him the next morning could hardly have been more forbidding. The train was halted outside the capital at the small station of Villaverde, lest there be clashes between monarchists and Falangists. As he stepped from the train, shuddering as the biting Castilian cold hit him, his heart must have fallen when he saw the grim welcoming committee. A group of unsmiling adults in black overcoats peered at him from under their trilbies. The Duque de Sotomayor presented them – Julio Danvila, the Conde de Fontanar, José María Oriol, the Conde de Rodezno – and as the boy raised his hand to be shaken, out came the empty formalities, ‘Did Your Highness have a good trip?’ ‘Your Highness is not too tired?’ Their stiffness was obviously in part due to the fact that middle-aged men have little in common with ten-year-old boys. However, it may also have reflected their own mixed feelings regarding the rivalry between Franco and Don Juan. For all that they were apparently partisans of Don Juan, their social and economic privileges were closely linked to the survival of Franco’s authoritarian regime. The Prince came from Portugal deeply aware of his loneliness. Surrounded by such men, he can only have felt even more lonely.

The extent to which he was just a player in a theatrical production mounted for the benefit of others was soon brought home to him. Outside the small station at Villaverde, there awaited a long line of black limousines – the vehicles of members of the aristocracy who had come to greet the Prince and to attend the ceremony that followed. Without any enquiry as to his wishes, the Duque de Sotomayor ushered him into the first car and the line of cars drove a few miles to the Cerro de los Angeles, considered the exact centre of Spain. There, his grandfather, Alfonso XIII, had dedicated Spain to the Sacred Heart in 1919. To commemorate that event, a Carmelite convent had been built on the spot. The sanctimonious Julio Danvila, ensuring that the boy should have no doubts about what Franco had done for Spain, hastened to tell him how the statue of Christ that dominated the hill had been ‘condemned to death’ and ‘executed’ by Republican militiamen in 1936. Still without his breakfast, the shivering child was then taken into the convent for what seemed to him an interminable mass. When mass was over, his ordeal continued. In a symbolic ceremony, he was asked to read out the text of his grandfather’s speech from 1919. Nervous and freezing, he did so in a halting voice. Only then was he driven to Las Jarillas, the country house put at his disposal by Alfonso Urquijo, a friend of his father.112

It was an awkward moment since, on the same evening that Juan Carlos left Lisbon, Carlos Méndez, a young monarchist, died in prison in Madrid. A large group of monarchists, who had attended the funeral at the Almudena cemetery, came to Las Jarillas to greet the Prince.

Many monarchists were demoralized by what they saw as Don Juan’s capitulation to Franco. The limits of the Caudillo’s commitment to a Borbón restoration were starkly brought home to Don Juan when Franco refused to permit the young Prince to use the title Príncipe de Asturias. A group of tutors of firm pro-Francoist loyalty was arranged for the young Prince. Juan Carlos expected to be received by Franco on 10 November at El Pardo but because of the situation provoked by the death of Carlos Méndez, the visit was postponed. It finally took place on 24 November. The ten-year-old approached the meeting with considerable trepidation and, as he put it himself, ‘understood little of what was being planned around me, but I knew very well that Franco was the man who caused such worry for my father, who was preventing his return to Spain and who allowed the papers to say such terrible things about him’. Before the boy’s departure, Don Juan had given his son precise instructions: ‘When you meet Franco, listen to what he tells you, but say as little as possible. Be polite and reply briefly to his questions. A mouth tight shut lets in no flies.’

The day of the visit was bitterly cold, and the sierra to the north of Madrid was covered with snow. The meeting was orchestrated with great discretion, with Danvila and Sotomayor driving Juan Carlos to El Pardo in the former’s private car and without a police escort. The Prince found the palace of El Pardo imposing, with its splendidly attired Moorish Guard at all of the gates. He had never seen so many people in uniform. Franco’s staff thronged the passageways of the palace, speaking always in low voices as if in church. After a lengthy walk through many gloomy salons, the Prince was finally greeted by Franco. He was rather taken aback by the rotund Caudillo who was much shorter and more pot-bellied than he had appeared in photographs. The dictator’s smile seemed to him forced. He asked the boy about his father. To Juan Carlos’s surprise, Franco referred to Don Juan as ‘His Highness’ and not ‘His Majesty’. To Franco’s visible annoyance, the boy replied, ‘The King is well, thank you.’ He enquired about Juan Carlos’s studies and invited him to join him in a pheasant hunt. In fact, the young Prince was paying little attention since he was transfixed by the sight of a little mouse that was running around the legs of Franco’s chair. Franco was, according to Danvila, ‘delighted with the Prince’.

As the interview was drawing to a close, Sotomayor shrewdly asked whether Juan Carlos might meet Franco’s wife. Doña Carmen appeared almost immediately, having been waiting for her cue. After being introduced, the Prince was taken by Franco for a tour of El Pardo, showing him, amongst other things, the bedroom in which Queen Victoria Eugenia had slept on the eve of her wedding, and which had been kept almost untouched ever since. Franco presented him with a shotgun and Juan Carlos then made his farewells. According to Danvila, in the car en route back to Las Jarillas, Juan Carlos said to him and Sotomayor, ‘This man is really rather nice, and so is his wife, although not as much.’ The Prince himself later claimed that the meeting had left no impression on him whatsoever. It is unlikely that the young Prince could have found Franco as ‘nice’ as Danvila reported after this first visit. Juan Carlos’s family had often spoken about the Caudillo in his presence, and ‘not always in complimentary terms’. In fact, as Juan Carlos’s mother would later recall, the Generalísimo was often referred to as the ‘little lieutenant’ in their household.113

The publicity given to the visit was handled in such a way as to give the impression that the monarchy was subordinate to the dictator. That, along with the torpedoing of the monarchist-Socialist negotiations, had been one of the principal objectives behind the entire Azor operation.114 At virtually no cost, Franco had left the moderate opposition in bitter disarray and driven a wedge between Don Juan and his most fervent and loyal supporters.115 Danvila would later recall the furious reaction in Estoril when Don Juan heard of this first meeting between Juan Carlos and Franco. Danvila was instructed thereafter not to let the young Prince carry out visits or attend any events that could be regarded as being in any way political. That the very idea of sending the Prince to Spain was a gamble for the family was revealed in a letter from Victoria Eugenia to Danvila: ‘I felt the greatest sorrow at having to be separated from the grandson that I love so much, but from the first moment that my son took the decision to send him to Spain, I respected his wishes without reservations … I approve of the search for a new direction in our policy since what we were doing before had provided no success and I believe that without risk there can be no gain. I pray to God that my son’s sacrifice produces a satisfactory result.’116 There could be no more poignant evidence of the fact that in the Borbón family, the sense of mission stood far above political principle and emotional considerations.

Franco had created a situation in which many influential members of the conservative establishment who had wavered since 1945 would incline again towards his cause. The press was ordered to keep references to the monarchy to a minimum. In international terms, the Caudillo had cleverly made his regime appear more acceptable. In the widely publicized report of a conversation with the British Labour MP for Loughborough, Dr Mont Follick, Franco declared that it was his intention to restore the monarchy although he sidestepped the question of when.117 In a context of growing international tension, the apparent ‘normalization’ of Spanish politics was eagerly greeted by the Western powers. Within less than a year, a deeply disillusioned Don Juan would order an end to the policy of conciliation.118 By then it would be too late, Franco having squeezed all possible advantage out of the pretended closeness between them.

CHAPTER TWO A Pawn Sacrificed 1949–1955

Juan Carlos’s new home was Las Jarillas, a grand Andalusian-style house, 17 kilometres outside Madrid on the road to Colmenar Viejo. One reason for its selection was its proximity both to El Pardo and the military garrison at El Goloso. A special direct telephone line to the base was installed in Danvila’s house in case of Falangist demonstrations against the Prince. Such daring would have been unlikely in Franco’s Spain and the nearest thing to public opposition was the singing of a ditty whose chorus went: ‘El que quiere una corona/que se haga de cartón/que la Corona de España/no es para ningún Borbón’ (He who wants a crown/better get a cardboard one/for the crown of Spain/will go to no Borbón). Shortly after his arrival, the boy suffered an acute bout of flu, perhaps another occasion on which the pain of separation from his parents was manifested physically.1 Used to absences from his family, Juan Carlos settled down relatively quickly at the school improvised for him at Las Jarillas. Although close to Madrid, it had not yet been overtaken by urban sprawl from the capital and still enjoyed an air of rural tranquillity. Its 100 hectares permitted hunting – mainly of rabbits. As it became obvious how much the Prince enjoyed shooting, he began to receive invitations to other hunts for larger prey such as wild deer and even wild boar.

Don Juan, with Franco’s approval, had hand-picked a group of tutors and eight aristocratic students. Four had been chosen from amongst Spain’s leading aristocratic families and others from the prosperous upper-middle classes: Alonso Álvarez de Toledo (son of the Marqués de Valdueza who, as an adult, would become an important figure in the Spanish financial world); Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias (Juan Carlos’s first cousin on his mother’s side, named for Juan Carlos’s maternal grandfather and godfather); Jaime Carvajal y Urquijo (son of the Conde de Fontanar); Fernando Falcó y Fernández de Córdoba (later Marqués de Cubas); Agustín Carvajal y Fernández de Córdoba (who would become an airline pilot); Alfredo Gómez Torres (a Valencian who would become an agronomist); Juan José Macaya (from Barcelona, who would become an economist and financial counsellor); and José Luis Leal Maldonado (the son of naval officer who was a friend of Don Juan, he would later be an important banker and Minister of the Economy from April 1979 to June 1980).

Juan Carlos was especially fond of his cousin, Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias, and the fact that they were allowed to share a room took the edge off his initial loneliness. During the Christmas holidays after his first term at Las Jarillas, the Prince had to write an essay on his school. It revealed more than just his disregard for punctuation: ‘On the day that I arrived, the boys were at the door waiting for me and I went in feeling really embarrassed with my Aunt Alicia and then we went upstairs it was a really nice room where we slept my cousin Carlos de Borbón is really nice because he is always saying daft things.’2

In his essay, Juan Carlos complained of how much he was obliged to study. Don Juan had given instructions that the work at Las Jarillas be hard and demanding. Years later, Juan Carlos would comment, ‘Don’t imagine that we were treated like kings. In fact, they made us study harder than in an ordinary school on the basis that “because we were who we were, we had to give a good example”.’ Certainly, Don Juan tried to ensure that his son’s academic abilities were assessed as impartially as possible. At the end of the academic year, the boys would indeed sit, at the Instituto San Isidro of Madrid, the public examinations taken by all Spanish children at ordinary schools. Juan Carlos would soon grow particularly attached to two of his tutors: José Garrido Casanova, the headmaster at Las Jarillas and founder of the hospice for homeless children of Nuestra Señora de la Paloma, and Heliodoro Ruiz Arias, the boys’ sports teacher. Garrido, a good and fair man of liberal views from Granada, was a brilliant teacher and warm and sympathetic human being. He made a profound impression on the Prince. Years later, Juan Carlos would say, ‘Sometimes, when I have to take certain decisions, I still ask myself what he would have advised me to do.’ Heliodoro had, in the 1930s, been the personal trainer of José Antonio Primo de Rivera. He saw in the young Prince great athletic potential and set himself the task of converting him into an all-round sportsman.3

Jaime Carvajal later came to the conclusion that their headmaster was ‘a key figure in the formation of Don Juan Carlos’s personality, after his father or even at the same level as Don Juan’. It was inevitable that, having been sent away by his own father, the boy would latch on to an appropriate father figure. Garrido had the sensitivity to realize that the Prince would be disorientated and confused after the brusque separation from his family. Accordingly, he treated Juan Carlos with real affection. Each night, he would check that he was comfortable, make a sign of the cross on his forehead and, after asking if he needed anything, turn out the light. He was quickly made aware of the sadness that the boy felt as a result of his situation. His father had given him a letter to hand over to Garrido. In it, he gave the teacher instructions about how he wanted his son to be educated. They read it together and, when they reached the part in which Don Juan spoke of his son’s responsibilities as representative of the family, tears appeared in the Prince’s eyes. It was a brutal reminder that his official position as Prince took precedent over the needs of a little boy trying to be brave. Garrido often noticed Juanito gazing sadly into the distance and then, as if realizing that he had no right to nostalgia, suddenly jumping up and riding his bike or taking out his frustrations on a football.

The Prince always endeavoured to hide his feelings but Garrido later recalled how much Juan Carlos enjoyed reading Platero y yo by Juan Ramón Jiménez, carrying the book with him everywhere he went during his first months at the school. One evening, the boy recited by heart a passage from the book as they watched the sunset. He startled Garrido by saying, ‘Mummy is on the other side.’ Garrido was moved and grew very fond of him, commenting years later, This child radiated affection despite the fact that they only ever spoke to him about duties and responsibilities.’ Garrido took particular interest in ensuring that the Prince’s relations with his classmates and with servants and gardeners were as natural as possible. In 1969, when Juan Carlos was named royal successor by Franco, he wrote to Garrido the following note: ‘I remember you with the greatest affection and every day allows me better to measure what I owe to you. You have helped me a lot with your example and your advice. And the counsels you gave to me were as good as they were numerous.’4

In contrast, Juan Carlos would later admit to an aversion for the dour Father Ignacio de Zulueta, an aristocratic Basque priest who visited Las Jarillas three times a week to supervise the children’s ethical and religious education. Tall and gaunt as if he had stepped down from an El Greco canvas, Zulueta was a forbidding figure. He had been recommended to Don Juan by the Duque de Sotomayor and Danvila because he represented the most conservative strand of Francoist thinking. Deeply reactionary, obsessed with royal protocol, Zulueta insisted on the entire class calling the young Prince by the title of ‘Your Highness’.5 Juan Carlos, desperate to be treated as an equal by his classmates, preferred that they call him ‘Juanito’ and used the informal ‘tú’ form of address. Accordingly, Zulueta’s instruction was usually ignored by the boys.6