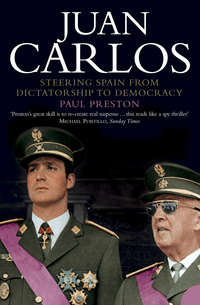

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

Within hours of the Prince’s arrival in Madrid, a queue of well-wishers, among them some aristocrats, had gathered outside the Palacio de Montellano. Like Franco, Martínez Campos was determined to ensure that there would be no entourage of courtiers at the palace. The Civil Guards on duty permitted those who came merely to sign the visitors’ book and then leave.

The year and a half spent in the Palacio de Montellano preparing for the entry examination for the Zaragoza military academy would be a hard trial for Juan Carlos. This time, he had no friends to accompany him. In his austerely furnished room, the only personal items were some family photographs, a tiny triptych of Christ and a luminous statue of Our Lady of Fatima. Martínez Campos established an inflexible routine that left the boy little spare time. The Prince was woken at 7.45 a.m. and had three-quarters of an hour in which to wash, hear mass in the chapel, have breakfast and glance at the newspapers. The hour from 8.30 a.m. to 9.30 a.m. was devoted to private study. At 9.30 a.m., accompanied by his maths tutor, Álvaro Fontanals Barón, the Prince would set off for his classes at the naval orphans’ college in Madrid where he followed a rigid timetable until 1.15 p.m. After lunch at the palace, there would be golf or horse-riding in the Casa de Campo until 5.00 p.m. Back at the palace, there would be more study until 9.00 p.m. at which time Juan Carlos was allowed an hour for letter-writing or telephone calls.

He had little free time since classes were held even on Saturdays and Father Aguilar often visited to impart religious and moral education. Other time was consumed by visits from distinguished academics who gave prepared talks on their specialities. The only glimmer of jollity in the otherwise stultifying atmosphere derived from the fact that a young friend, Miguel Primo de Rivera y Urquijo, the nephew of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, lived nearby and thus became the Prince’s frequent companion. It was to develop into a lifelong friendship. At the time, it helped relieve the tedium of the regular lunch and dinner visits from important figures in the Church, the Falange, and the business world – including the head of the Opus Dei, Padre Josémaría Escrivá de Balaguer. This austere routine was rarely stimulating – indeed, if anything, it was utterly suffocating – for an adolescent. Asked by the diplomat José Antonio Giménez-Arnau how he felt about his loneliness and the absence from his family, Juan Carlos replied sadly, ‘If not resigned, I’m at least used to it. Just imagine! When I was six, I spent two years separated from my parents when they were first in Estoril. There was no choice.’ Giménez-Arnau had been commissioned to write a feature article on the Prince. When it was published, Juan Carlos wrote him an informal note of thanks. The unaffected warmth and openness of the 17-year-old Prince’s note guaranteed the lifelong loyalty of its recipient.71

Occasionally, the Prince was taken to El Pardo where the Caudillo subjected him to interminable history lessons about the mistakes made by various kings of Spain. He also gave him sententious advice about the need to avoid aristocrats and courtiers. Believing that the Prince was extremely pleased and grateful, Franco decided to see him at least once a month, ‘to chat with him and carry on instilling my ideas in him’. The Caudillo was delighted by the severity of Martínez Campos who reported to him on 5 March 1955. When the Prince had begun to tutear (use the intimate ‘tú’ form of address to) Major Valenzuela, the general had energetically forbidden it. He had refused the Prince permission to go to Lisbon for the wedding of one of the daughters of the ex-King Umberto of Italy, informing Don Juan that it would constitute an unacceptable interruption of the boy’s studies. He insisted on speaking English with Juan Carlos. He also made every effort to ensure that no particular one of the Prince’s friendships came to take priority over the others. That Martínez Campos felt it necessary to report to Franco gives some indication of the ambience in which the Prince was being educated. He was permitted, on occasions, to invite friends to lunch. Once, he was visited by the beautiful Princess María Gabriella di Savoia, King Umberto’s other daughter, a friend and fellow-exile from Portugal, who later became his girlfriend. The Prince was usually short of cash, later recalling how Major Cotoner had to buy him a suit for the occasion.72

The tendency to high spirits that had characterized Juan Carlos as a schoolboy did not desert him despite his austere surroundings. One of the teaching staff, the Air Force Major Emilio García Conde, had a Mercedes that the Prince loved to drive, even though he did not possess a driving licence. One day, on a trip to the headquarters of the Sección Femenina (the women’s section of the Falange) at the Castillo de la Mota in the province of Valladolid, he had a minor accident involving a cyclist. Major García Conde resolved the problem by giving the cyclist some banknotes to get his wheel fixed and buy a new pair of trousers. After nearly being eaten alive by the enthusiastic women of the Sección Femenina, Juan Carlos and his party retired to lunch in a restaurant. The Prince delightedly recounted the bicycle incident and was astonished when Martínez Campos furiously ordered García Conde to find the cyclist, get the money back and oblige the unfortunate young man to report the incident to the Civil Guard. He was worried that if the young man was seriously injured, it would look as if the Prince was involved in corruptly trying to cover up his own involvement. He insisted that Juan Carlos return to Madrid in his car.73

General Martínez Campos’s loyalty and deference to the Caudillo prevented him from complaining about the fact that Franco, partly to please the Falange and partly to bring the monarchists to heel, had encouraged criticism of Don Juan in the press. In consequence, as the general knew full well, hostility to the monarchy soon began to be directed against Juan Carlos. At the beginning of February 1955, the Mayor of Madrid wrote to Franco’s cousin, Pacón. In response to the scattering of Falangist leaflets bearing the inscription ‘We want no king!’, the Mayor asked how it was possible, if Franco wanted Juan Carlos educated in Spain, that the regime’s single party should be engaged in insulting the Prince. When Pacón mentioned this to the Caudillo, he brushed it aside as ‘student antics’. However, the rumblings came from much higher in the Falange, including Pilar Primo de Rivera, the head of the Sección Femenina. Nevertheless, Franco brushed aside further reports about anti-monarchist activities from such dignitaries as the Captain-General of Valencia. The mutter-ings continued and, eventually, on 26 February, the Caudillo felt obliged to inform a concerned cabinet that ‘a King would be nominated only if there were a Prince ready for the task’.74

Juan Carlos’s presence in Spain and its possible implications were highlighted by the publication in ABC on 15 April 1955 of his interview with José Antonio Giménez-Arnau – the first press interview published since his arrival in Spain in 1948. A few days later, violence broke out between Falangists and monarchists at the end of a lecture on European monarchies given by Roberto Cantalupo, once Mussolini’s Ambassador to Franco, at the Madrid Ateneo, the capital’s leading liberal intellectual centre. In response to Cantalupo’s enthusiastic advocacy of monarchy, Rafael Sánchez Mazas, a former minister of Franco, cried ‘¡Viva la Falange!’ in reply to which shouts of ‘¡Viva el Rey!’ or ‘¡Viva Don ]uan III!’ were heard from monarchists present. Falangists then showered the hall with leaflets ridiculing Juan Carlos and the police had to be called to put a stop to the fight that erupted. The Prince also faced the increasingly overt hostility of the then Minister for the Army, General Agustín Muñoz Grandes, whose sympathies lay with the Falange. Later on that spring, young Falangists roamed the streets of Madrid shouting: ‘We don’t want idiot kings!’ Juan Carlos was also booed while he was giving out the prizes at some horse trials, and, in the summer, he was insulted during a visit to a Falangist summer camp.75

The noises coming from Falangists were the dying agony of a wounded beast. In reality, their organization could not have been more domesticated. On 19 June 1955, the Secretary-General of the Movimiento, Raimundo Fernández Cuesta, declared in a speech made in Bilbao that to ensure the survival of the regime after Franco’s death, judicial, political and institutional guarantees would be necessary. The role of the Movimiento would be to sustain the monarchy that succeeded Franco and to keep it on the straight and narrow path of Francoism. It was the formal recognition by the Falange of the inevitability of a monarchical succession.76 For their part, the monarchists had to accept that the monarchy would be restored only within the Movimiento. To hammer this home, Franco exploited the anxiety of the sycophantic Julio Danvila, the most Francoist of Don Juan’s advisers, to further the establishment of a Francoist monarchy. At Franco’s behest, the willing Danvila concocted the text of an ‘interview’ with Don Juan in which he apparently gave royal approval to Fernández Cuesta’s speech. Franco agreed the text, which Danvila then took to Estoril where an indignant Don Juan refused to agree to its publication. Danvila then told the Caudillo that the Pretender had accepted the ‘interview’, at which point Franco amended the text to bring it even more into line with his own thinking and obliged ABC and Ya to publish it on 24 June 1955. Although outraged, Don Juan did not protest, since a public break between himself and Franco would have encouraged the anti-monarchical machinations of the extremist elements of the Falange. It might also have led to the termination of Juan Carlos’s education in Spain.77

Franco was unconcerned about the Falangist rejection of his apparent choice of conservative monarchism as the future of the regime. At the November 1955 rally in El Escorial to commemorate the anniversary of the death of the Falange’s founder, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, Franco rekindled Falangist anxieties about his Las Cabezas meeting with Don Juan and the presence of Juan Carlos in Spain. He had arrived for the ceremony in the uniform of a Captain-General instead of the usual black uniform and blue shirt of the Jefe Nacional (National Chief of the Movimiento). There was some nervous shuffling in the ranks of the assembled Falangists. As Franco walked across the square towards his car, a voice called out: ‘We want no idiot kings.’ It has also been alleged that a cry of ‘Franco traitor’ was heard. There were other minor incidents reflecting Falangist discontent with the complacency of the regime that Franco dismissed as of little consequence.78

The constant running down of the Borbón monarchy, together with Franco’s assumption of royal airs, deeply annoyed Don Juan and his family. This was reflected in the indiscreet comments of Alfonso de Borbón, the second son of Don Juan. When he was 14 years old, Alfonsito was wont to refer to Franco as ‘the dwarf or ‘the toad’. He said, ‘That fellow won’t leave. He has to be kicked out … Having to visit him makes me vomit and la Señora, always showing her teeth, kills my appetite.’ It was an indication both of Don Juan’s deteriorating relations with Franco and the fact that Alfonsito was such a favourite that his outbursts were tolerated and praised. Not many years before, Don Juan had smacked his daughter Margarita for repeating a joke about Franco. Things had changed and there can be little doubt that critical remarks about Franco or his wife would quickly have been relayed to El Pardo by the many monarchist visitors who maintained a dual ‘loyalty’.79

CHAPTER THREE The Tribulations of a Young Soldier 1955–1960

Despite Franco’s readiness to excuse Juan Carlos the entry examinations for the Zaragoza military academy, General Martínez Campos insisted that he undergo the test just like any other prospective cadet. Having passed, Juan Carlos joined the academy in December 1955. As his companions from the academy would later recall, the exams were very difficult and they believed that, although the Prince was usually treated like any other candidate by the examiners, the mathematics test he sat must have been easier than the one they took: indeed, Juan Carlos would soon be shown to be well below average in this subject.1

Although Juan Carlos, in his public declarations at least, would later recall his years as a cadet with nostalgic fondness, his time at the military academies did not always go smoothly. When he took his oath of loyalty to the colours on 15 December 1955, the ceremony was chaired by the brusque General Agustín Muñoz Grandes, the Minister for the Army, who was much more inclined to the Falangist than to the monarchist cause. Accordingly, in his speech, he made no mention of the Prince.2 In addition, Juan Carlos was saddened on this occasion by the fact that Franco had not permitted his father to attend the ceremony.3 On 10 December, Don Juan wrote to him, reminding him of the tremendous responsibilities he would be undertaking when he swore his loyalty to Spain: ‘15 December will be a great day because it is the day on which you will knowingly consecrate the rest of your life to the service of Spain.’ Juan Carlos sent his father a telegram: ‘Before the flag I have promised Spain to be a perfect soldier and with tremendous feeling I swear to you that I will fulfil that oath.’4

It was Juan Carlos’s fervent wish to be allowed to get on with life as an ordinary cadet. ‘You can avoid a lot of problems by getting lost in the crowd.’ That was rendered impossible because the campaign against Don Juan in the Movimiento press remained intense during this period. Juan Carlos found these constant attacks on his father upsetting. Some of his fellow cadets would derive a malicious pleasure from quoting the insinuations of the press. On several occasions, Juan Carlos was sufficiently provoked by remarks that his father was a freemason or a bad patriot (for serving in the Royal Navy) to get involved in fights. These were organized furtively in the stables at night, possibly even with the complicity of the teaching staff. When Juan Carlos eventually complained to Franco about the media’s attacks on his father, the Caudillo replied, with his habitual cynicism, that the Spanish press was independent and that he had no influence over it. He stated that, ‘it was impossible to do anything, since the press was free to express its opinions.’ As Juan Carlos commented, ‘it was such an outrageous lie that all I could do was laugh.’

Recounting this later, Juan Carlos was rather benevolent with regard to Franco. Reflecting on the fact that the Caudillo saw in Don Juan a dangerous liberal, he commented, ‘When my father said “I want to be King of all Spaniards,” Franco must have translated this as “I want to be King of the victors and of the vanquished.”’ This puzzled Juan Carlos, because of the fact that Franco knew full well that Don Juan had tried to join the Nationalist forces against the ‘reds’. Referring to the cunning letter with which Franco had refused Don Juan’s offer, Juan Carlos commented rather uncritically, ‘On that occasion, the General wrote my father a very beautiful letter to thank him for his gesture. In it, he told him that his life was too precious for the future of Spain and that he forbade him to risk it at the battle front. Why was my father’s life precious if not because he was the heir to the crown? But, what can you say … that was the General for you. At times, putting up with him was very difficult. But, as you know, I had totally convinced myself that to achieve my objectives I had to put up with a lot. The objective was worth the trouble.’ The objective was the re-establishment of the Borbón family on the throne.5

Despite these occasional outbursts of hostility towards his father, Juan Carlos would later recall his years in the military academies as amongst the happiest in his life. In a brief letter to the readers of a Spanish magazine which published, in 1981, a feature on this period, he wrote: ‘I remember my years at the military academies with genuine satisfaction and nostalgia … Now that my post and occupations leave me hardly any time or freedom, I often think back to that distant period in which my life evolved in a way so different from the current one.’

Above and beyond the special status, of which none of his fellow students could remain ignorant, Juan Carlos soon became a genuinely popular cadet. His contemporaries at the academies would later describe him as a ‘sensational companion’, outgoing, generous, particularly gifted at sports and endowed with an extraordinary memory. His ability to remember people’s names and faces would later enable him to recognize and greet comrades and teachers whom he had not seen in years. He had a good sense of humour and enjoyed playing practical jokes on his friends. He often participated, for instance, in the food fights that occasionally erupted at lunch times in the refectory. Academically, he was said to be of ‘average intelligence’, but above average in ‘general knowledge’, foreign languages, tactical thinking and military ethics. He struggled with mathematics, which was ‘the subject dreaded by all’. Juan Carlos was also perceived as being deeply religious: every day, he would get up before reveille in order to attend the voluntary, early morning mass.

When it came to friendships, the Prince necessarily had to be careful, making every effort to avoid the creation of a circle of admirers or sycophants who wanted to be with him only out of self-interest. He tried to get to know as many people as possible, which was made easier by the fact that the class groups changed every term. He was aware of the dangers of nepotism: indeed, at the end of his military training, he refused to use his influence in order to get plumb postings for his friends from the academies. He did, however, strive to keep in touch with his old companions, attending and often even organizing reunions.6 Not all of his contemporaries were keen to flatter him: ‘Some thought that I was a spoilt brat, spoiled by destiny, a daddy’s boy, the inhabitant of another planet. I had to use my fists to become one of them.’7 To this end, he encouraged his peers to treat him with considerable informality. His close friends called him ‘Juan’ or ‘Juanito’, or even ‘Carlos’, whilst his other companions addressed him with the informal ‘tú’ and jokingly called him SAR, an abbreviation of ‘Su Alteza Reaf’ (His Royal Highness).8

This easy-going informality outraged General Martínez Campos who visited the academy each weekend to review the Prince’s progress and have lunch with him. On one occasion, Martínez Campos allowed his tutee to invite a couple of his academy friends to join them for lunch. During the meal, when he heard one of these friends call the Prince ‘Juan’, he exploded. Red-faced with fury, he leapt to his feet, knocking his chair out of the way and shouted at the culprit: ‘Gentleman cadet! On your feet and stand to attention! How dare you, gentleman cadet, address informally and by his first name someone that I, a Lieutenant-General, address as His Royal Highness!’ Unsurprisingly, Juan Carlos was never again able to convince his friends to join him for lunch with Martínez Campos.9 Juan Carlos soon came to dread these visits from his supervisor, turning pale and trembling as the meeting time came closer.10

The teaching staff at the academy addressed Juan Carlos as ‘Your Highness’ and, at roll-call, he was referred to by his full title – ‘His Royal Highness Juan Carlos de Borbón’. That aside, in so far as it could be put aside, Juan Carlos was, according to his contemporaries, treated by the teaching staff just like any other student. He was disciplined like any other cadet when he broke the rules. Once, for instance, he was put under house arrest for being caught smoking indoors. The Prince was subject to the same timetable as the other students, which left them very little free time. Reveille was at 6.15 a.m., although Juan Carlos rose earlier in order to attend mass. By 6.30 a.m., all cadets had to be standing to attention in the corridors, where roll-call took place. The young men were then allowed to take their showers – in water usually either freezing or so hot as to be almost unbearable. Individual study time followed, then lessons, lunch, a half-hour break, further lessons, another half-hour break and dinner. According to his contemporaries, no one was ever asked by the teaching staff to make allowances for the Prince or to treat him with special deference. In his first year at Zaragoza, Juan Carlos was thus subjected to the same ‘novatadas’ (initiation tests) and other pranks as the other newly arrived students. Years later, he remembered not only many of the pranks played on him on his arrival at Zaragoza, but also their names: ‘I had to undergo everything. I had to do the “reptile” on the bedroom floor. I slept with the “nun” [with a sabre resting on his chest]. They “X-rayed” me [they made him sleep between two planks from the bedside table]. I also had to let them “clay pigeon shoot” me [he was left in a room blindfolded and, when he attempted to leave, he was battered with pillows].’11

Juan Carlos enjoyed being an ordinary cadet and even made an effort to prevent the teaching staff giving him preferential treatment. He once complained, for instance, that the mathematics tutor gave him an undeserved grade. According to his fellow students, the Prince had a ‘natural sense of justice’. Prudently, he used his special status only in order to help others. For instance, when a companion had been punished for some misdemeanour by being deprived of pudding, Juan Carlos would complain that there was something wrong with his helping in order to get an extra one to pass to the friend.12

Nevertheless, it was inevitable that there would be differences in the way that Juan Carlos was treated at the Zaragoza military academy. He travelled into the centre of Zaragoza by car, a black SEAT 1500, whereas his contemporaries did so by tram. Although, while out on manoeuvres, he slept on the floor of a tent like everyone else, in the academy, he had an independent, though small, bedroom, while the others slept in communal dormitories. According to one of his Zaragoza companions, Juan Carlos’s bedroom, which was situated above the infirmary, was Spartan. The only objects in it, besides a bed and a desk, were a multiple photograph frame displaying the pictures of all of the Borbón kings of Spain – including his father. He had pictures of his mother, his brother and his two sisters and a girlfriend, María Gabriella di Savoia. His book collection was small – a few textbooks and next to his bed usually was a novel by Marcial Lafuente Estefanía, from the ‘Rodeo’ collection of western stories popular at the time. Juan Carlos enjoyed less freedom than the others. He was obliged to have extra lessons and saw his private tutors during the morning period that should have been for individual study, during the afternoon breaks and sometimes at weekends. On the occasions when it was possible to go out for drinks in Zaragoza with his friends, they were delighted to be able to use his status and his unusual blond good looks as a ploy to get to know girls. When the cadets were on trains en route to camp, at each station women would come out to say hello to him. His ability to pick up girls was as unlimited as a capacity for falling briefly in love.13

In March 1956, there occurred an incident which totally diverted Juan Carlos from any thoughts of girls or even of the crown. He and his 14-year-old brother had travelled from Spain on the Lusitania Express to spend the Easter holidays in Estoril with their parents and sisters. It was the first time for some months that Don Juan and Doña María de las Mercedes had had all four of their children together. Alfonsito was a pupil at the lycée in Madrid and was about to become a cadet at the Spanish naval college at Marín near Pontevedra. Alfonsito was regarded as the family favourite, witty, intelligent and more simpático than his rather introspective elder brother. His passion for golf and sailing had brought him particularly close to Don Juan.14